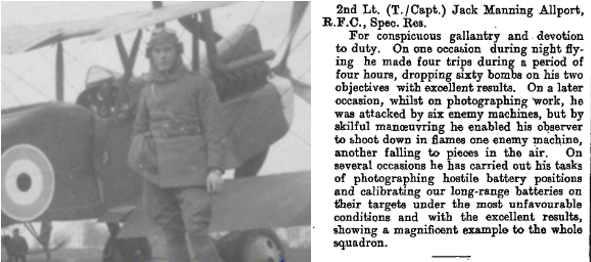

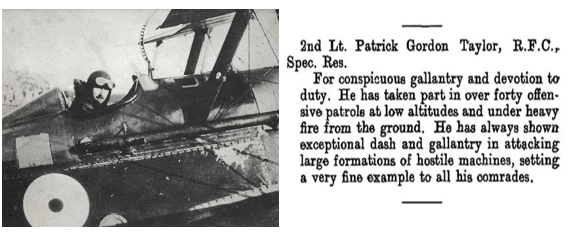

Capt. J.M. Allport stands beside his Re8 and Capt. P.G. Taylor in the cockpit of an Se5a.

Capt. J.M. Allport stands beside his Re8 and Capt. P.G. Taylor in the cockpit of an Se5a.

‘Bill’ Taylor and Jack Allport’s paths crossed, albeit briefly, in England’s green and pleasant fields. At the time 2nd Lieutenant Taylor was training to be an aviator, and Gunner J.M. Allport was looking to the skies…

‘Bill’ Taylor’s memoirs were published, posthumously, in 1968. In 1969 Jack Allport was interviewed about his war service. Both men grew up in Mosman, went to the same schools, and shared a similar rite of passage getting into the Royal Flying Corps.1A considerable attraction near Salisbury plain

Soldiers crowd around a Maurice Farman pusher biplane aircraft that came down near their camp in Wiltshire. Maurice Farman aircraft were nicknamed Longhorn or Shorthorn because the rumbling noise they made reminded people of cattle. Source: AWM.

Soldiers crowd around a Maurice Farman pusher biplane aircraft that came down near their camp in Wiltshire. Maurice Farman aircraft were nicknamed Longhorn or Shorthorn because the rumbling noise they made reminded people of cattle. Source: AWM.

When asked why he joined the RFC, Capt. Allport replied:

Oh, yes. We really got the idea on Salisbury Plains, because an Australian, with a B.E.[2c], happened to land near the Artillery Unit. We were greatly interested in this plane, and it turned out to be Bill Taylor; that’s the late Sir Gordon Taylor.

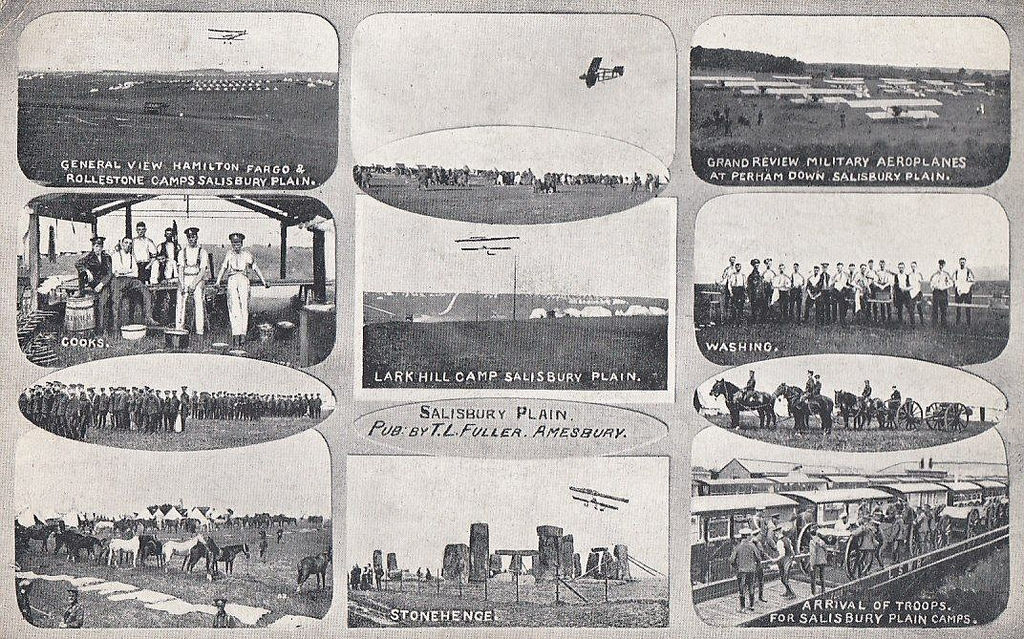

Postcard showing recruits training at Salisbury including aircraft over Stonehenge

Postcard showing recruits training at Salisbury including aircraft over Stonehenge

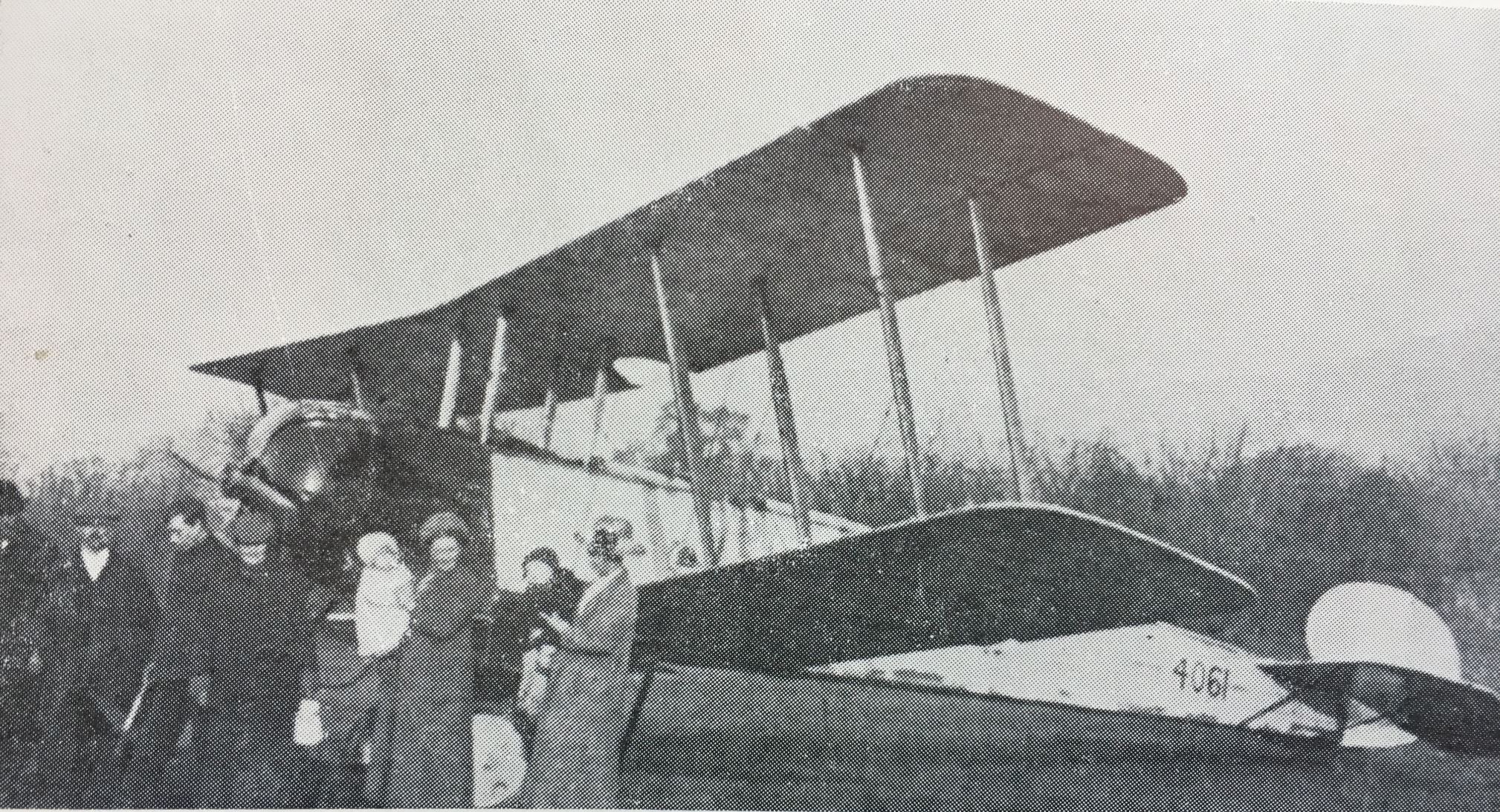

Bill Taylor forced to land on his first trial photographic run, felt shame and panic at being lost. He managed to quickly calm his mind and land on a small grassy strip, just missing a hedge. After cutting the engine came he sighed. What a relief. He was in one piece. So was the ‘Old 2C’.2

…People came running from various directions. An aeroplane landing in a field was a considerable attraction. But I wasn’t interested in being the centre of an admiring audience. The light was fading fast, and I wanted to know the way to Upavon. Nobody could tell me. All I got were looks of incredulous astonishment. Fancy an airman wanting somebody to show him the way to his aerodrome!

Just as I was getting desperate, an Army lorry drew up by the side of the road…after a certain amount of deliberation, accompanied by much confusion and argument from the onlookers, he pronounced judgement and pointed in the direction…I established this direction in my mind..Then I thought of fuel..Again the driver came to my rescue. He had a spare can of petrol, and this we emptied into the tank of the aeroplane…With the driver on the throttle, I swung the propeller and started up the engine…3

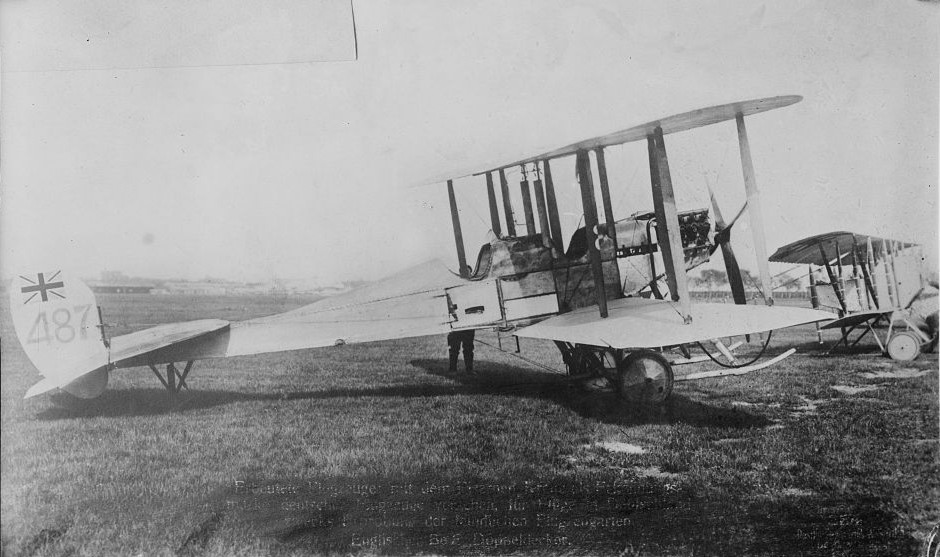

Be2c, the type P.G. Taylor was flying when forced to land, as described by J.M. Allport . Taylor described the aircraft as an ‘ugly but stable two-seater biplane with a 70 hp V8 engine’.

Be2c, the type P.G. Taylor was flying when forced to land, as described by J.M. Allport . Taylor described the aircraft as an ‘ugly but stable two-seater biplane with a 70 hp V8 engine’.

This was not to be Taylor’s first or last forced landing. On another occasion he ended up in a golf course bunker, near Bath, after the dodgy engine in his C.O.‘s Avro seized up.

A wave of relief swept over me. I had got away with it. I had avoided crashing GB’s Avro. Almost within seconds, people started to appear in the field, running towards the aeroplane. Where they came from on these occasions I don’t know, but on the four occasions4 I made a forced landing before going to France they sprang immediately from the apparently deserted countryside.

From ‘Sopwith Scout 7309 captioned ‘GB’s Avro- the blighted 4061 – in the field near Devizes where I forced-landed it on my way from Upavon to Filton.’

From ‘Sopwith Scout 7309 captioned ‘GB’s Avro- the blighted 4061 – in the field near Devizes where I forced-landed it on my way from Upavon to Filton.’

Hot air and red tape

Allport, after seeing Taylor’s landing, applied for the Flying Corps:

Our official application went forward, at that time to, I think it was Adastral House. We both had many interviews, medicals, and a lot of hot air and red tape, of course, but we were accepted.5

Taylor fills in some more details about the interview process:

Equipped with a dossier on my personal Service background (a full and very carefully prepared brief, incidentally), I set off apprehensively one morning for Adastral House, a building on the Thames embankment near Blackfriars Bridge and at that time the London Headquarters of the Royal Flying Corps. After a very brief wait in the foyer, I was shown by a polite and friendly attendant (that was a good start) to a room at the end of a passage. I was told to go in.

Adastral House (later Television House) was the London H.Q. of the RFC and RAF. Source: Wikipedia

There I was confronted by a colonel, sitting at a table with his back to the light and a tree outside the window. After receiving a brief scrutiny, I was invited to sit in a chair in front of the table. The colonel came straight to the point.

‘You want to join the Royal Flying Corps?’

‘Yes, sir. I do.’

‘What is your name?’

I told him

‘Australian, aren’t you?’

‘Yes, sir. I’ve come from Australia to join the RFC. I want to fly as a pilot.’

A few conventional questions followed. Who I was, where I had come from, what I had been doing. My dossier remained unopened.

Then, ‘Tell me, can you ride a horse?’

‘Yes, sir.’

He was looking at me shrewdly, with real interest.

‘Good.’

I had the impression that all the rest of the conversation had been superfluous. It seemed that I was now accepted. I was now in the R.F.C. I don’t remember even having a medical examination…At this time, the summer of 1916, a pilot wasn’t very likely to live very long anyway.

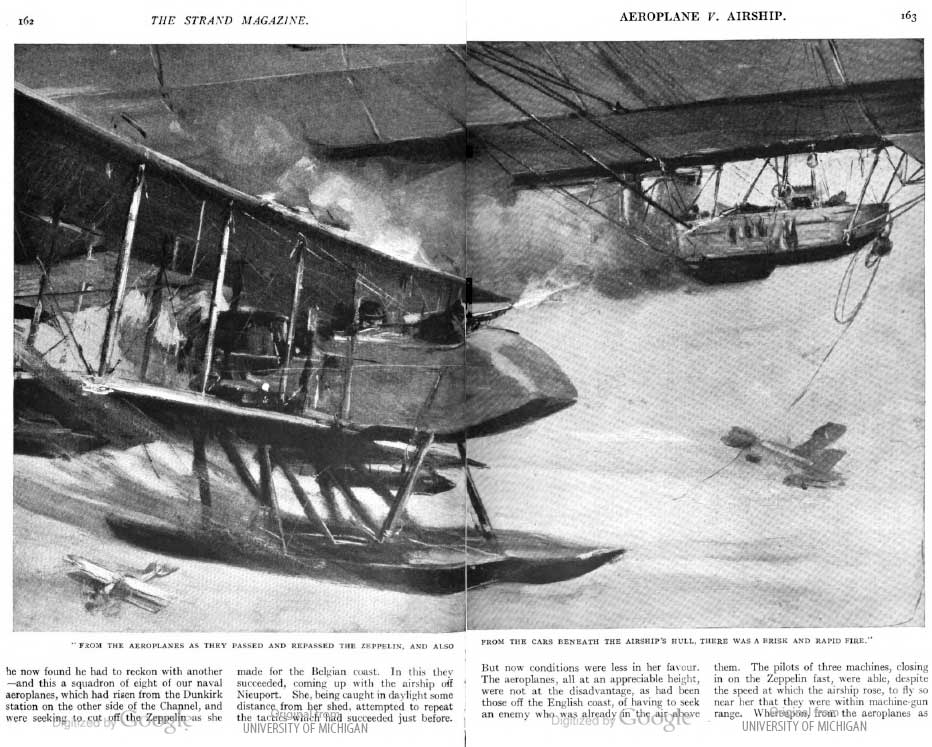

As I walked out of Adastral House that day I already felt I was flying. It was a long way back to the evening when I had seen the picture in the Strand Magazine ,6 and the journey to London had been like finding ones way through a dream landscape to a dream destination. Now my destination had a reality, exciting and immediate.

AEROPLANE V. AIRSHIP. The Strand Magazine, 1916. See: Raglan St. to RFC: Bill Taylor’s school days & calling to the skies.

AEROPLANE V. AIRSHIP. The Strand Magazine, 1916. See: Raglan St. to RFC: Bill Taylor’s school days & calling to the skies.

Crash courses.

Jack Allport ended up at Brasenose College, Oxford University after a stint at Denham where they had got a dose of ‘real English, Company Sergeant Major, Guardsman style’ discipline.

Brasenose College, Oxford ‘…we settled down there, to cram for the next stage…’ Image source: Wikipedia

Four of us, a South African, a Scot, an Englishman, and myself, hired furniture and made cur digs, which were the accommodation for the ordinary Oxford students, very comfortable and we settled down there, to cram for the next stage, which was instruction on squadron organisation, the theory of flying, reconnaissance, map reading, engines, rigging, plane construction, instruments, and types of bombs etc….It was actually a “High Pressure” course. We were probably working quite a number of hours per day on the course, more than if it had been the normal course.

They gave special emphasis to co-operation with artillery. I suppose I was earmarked for an artillery observation, artillery co-operation plane, having been in the artillery when I enlisted. The set up there was very comprehensive, they had a Theatrette with gallery seats, and it was equipped with a complete countryside landscape, with enemy battery positions, and small flashing lights representing guns firing, and the shells bursting. The pupils in the gallery were required to pinpoint these, and send corrections down by Morse code on a buzzer, which was provided…I can assure you that the impact of this system in France, and the application of it, had a terrific effect on the efficiency of our gunnery.

Allport would put the artillery-spotting diorama training to good use. They were ‘superfluous’ to Taylor, who remained an aspiring fighter pilot.7

Taylor studied at Reading University, with digs at Wantage Hall. It was here that he befriended ‘Anzac’ Whiteman from Western Australia. Whiteman, a Rhodes Scholar passed the exams, ‘as was to be expected.’ Taylor admitted ‘examination nerves bothered me’, and was relieved to have ‘scraped through’ to the next stage: flight training.

Now you land it!

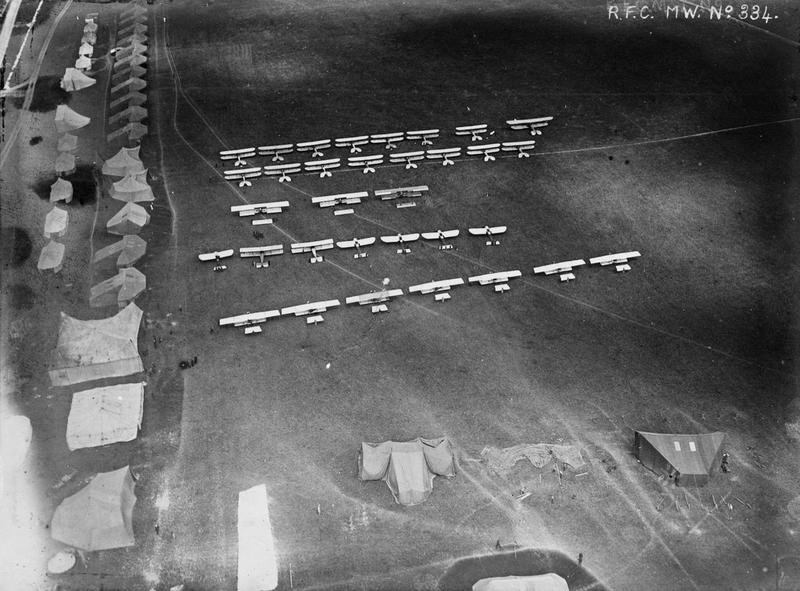

RFC aircraft and tents at Netheravon, June 1914. Source: Wikipedia

RFC aircraft and tents at Netheravon, June 1914. Source: Wikipedia

When asked, Jack Allport said learning to fly was less about the type of aircraft, and more about the quality of the instructor:

We seemed to get a different instructor each time we went up…you couldn’t stunt, it was only a matter of off the ground, round, and landing again.

There was no means of intercommunication, and the pupil had no idea what the instructor may have been doing in actual fact, but, if the pupil handled the controls too heavily, he got a punch on the side of his head, which meant “Let go everything”…

Landings were the first hurdle for a trainee pilot:

After the first solo of course, the thing to do was to practice landings, and it seemed easy to take off and fly around, but to come down was quite another thing. The pilot thought about landing too heavily, or meeting the ground at too steep an angle. With an engine revolving behind your back, it made you think perhaps of the mechanics scraping bits of you out of the fins of the cylinders.

I have seen many a pilot who just couldn’t make it down, and he just opened his throttle out and around again, then he would fly around a while and eventually he would run out of petrol…

Doncaster, England. 1917-03. Starboard view of a French Maurice Farman Shorthorn aircraft, serial no. 77, at the aerodrome. Source: AWM. In the words of P.G. Taylor ‘…the Maurice Farman ‘Shorthorn’, all struts and wires and homely, clattering engine…The fuselage was an open frame and the angular appearance of the aircraft was accentuated by the projecting wheel skids and the mass of wires and struts which held the whole assembly together…’

Doncaster, England. 1917-03. Starboard view of a French Maurice Farman Shorthorn aircraft, serial no. 77, at the aerodrome. Source: AWM. In the words of P.G. Taylor ‘…the Maurice Farman ‘Shorthorn’, all struts and wires and homely, clattering engine…The fuselage was an open frame and the angular appearance of the aircraft was accentuated by the projecting wheel skids and the mass of wires and struts which held the whole assembly together…’

Bill Taylor described his first trainee flight:

I was suddenly confronted by a morose instructor who, with a few words, launched me into my first experience of flight.

‘You Taylor?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Had any instruction yet?’

‘No I haven’t, sir.’

‘All right, I’ll give you some landings.’

With these brief words he walked off towards a Maurice Farman standing on the tarmac and I followed him in a somewhat confused state of mind. This wasn’t what I had expected. I had pictured some sort of…a talk with the instructor before my flight, and some idea of the theory behind controlling an aeroplane. Instead, I climbed up after my instructor into the rear seat of a thing about the size of a bathtub, slung between the wings of a biplane.

UNITED KINGDOM. C. 1917. FOUR MEMBERS OF THE AUSTRALIAN FLYING CORPS WITH A MAURICE FARMAN SHORTHORN BIPLANE MF11. THIS PHOTOGRAPH WAS PROBABLY TAKEN AT N0 5 (TRAINING) SQUADRON AT SHAWBURY. (ORIGINAL PRINTS HELD IN AWM ARCHIVE STORE) (DONOR M. CORKHILL) Source:AWM. Allport mentioned: They were simply constructed planes, the controls were duplicated of course, and the pupil usually sat in the nacelle, in front of the instructor and slightly below him. The pupil was allowed to lightly feel the dual controls and get the idea. [Author’s note: As demonstrated in the above photograph.)

UNITED KINGDOM. C. 1917. FOUR MEMBERS OF THE AUSTRALIAN FLYING CORPS WITH A MAURICE FARMAN SHORTHORN BIPLANE MF11. THIS PHOTOGRAPH WAS PROBABLY TAKEN AT N0 5 (TRAINING) SQUADRON AT SHAWBURY. (ORIGINAL PRINTS HELD IN AWM ARCHIVE STORE) (DONOR M. CORKHILL) Source:AWM. Allport mentioned: They were simply constructed planes, the controls were duplicated of course, and the pupil usually sat in the nacelle, in front of the instructor and slightly below him. The pupil was allowed to lightly feel the dual controls and get the idea. [Author’s note: As demonstrated in the above photograph.)

Taylor, like Allport, noticed the engine’s position directly behind him:

…Though I was full of enthusiasm for the great adventure which was about to begin, I couldn’t help noticing the engine and pusher airscrew were conveniently located to come right through the back of my neck in the event of a crash dislodging them from their mountings…

My instructor said nothing…Having received no instructions at all, I thought it best not to touch anything; so I kept my hands and feet off the controls.

They got airborne and circled the field. This exhilaration was short-lived:

…the nose went down, and a shout came from the figure in the front seat, ‘Now you land it!’

The controls were snatched out of my hands and a savage shout came back to me from the instructor ‘Bloody awful!’ Again we climbed away, went seeping round the circuit and in for another landing. I tried to anticipate the next command, but none came and I just sat there, feeling utterly confused and ineffectual.

Visibly acknowledging my existence for the first time the instructor turned slightly and announced a more conciliatory tone,

‘That’s better.’

‘What’s better?’

I thought. Then his meaning hit me, and with it a surge of fear about the whole mad act. I hadn’t touched the controls. To this day I still have no idea how the aeroplane was landed

The instructor hurriedly got out of the cockpit:

…To my utter astonishment, he looked up and shouted to me

‘You can bloody-well go solo now.’

Taylor cut the engine. The instructor turned and came back in a state and shouted:

‘What’s the matter with you? Why did you stop the engine?’

I shouted back at him. ‘I’m not going solo.’

I couldn’t fly the aeroplane and wouldn’t attempt to. I had never done a take-off, nor a landing without interference, and during the total hour and a half of this nightmare experience I had only flown the machine straight and level even. I hadn’t come all the way from home in Australia to kill myself at an instructor’s orders.

The instructor was surprisingly obliging. Taylor, as he had requested, was given a new instructor. His 2nd instructor proved to be competent and provided proper training.

UNITED KINGDOM. C.1917. A MAURICE FARMAN SHORTHORN MF 11 TWO SEAT BIPLANE TRAINER AIRCRAFT WITH A 7O HORSE POWER RENAULT ENGINE, USED BY NO. 5 TRAINING SQUADRON, AUSTRALIAN FLYING CORPS. (DONOR M. CORKHILL) (ORIGINAL PRINTS HELD IN AWM ARCHIVE STORE) Source: AWM.

UNITED KINGDOM. C.1917. A MAURICE FARMAN SHORTHORN MF 11 TWO SEAT BIPLANE TRAINER AIRCRAFT WITH A 7O HORSE POWER RENAULT ENGINE, USED BY NO. 5 TRAINING SQUADRON, AUSTRALIAN FLYING CORPS. (DONOR M. CORKHILL) (ORIGINAL PRINTS HELD IN AWM ARCHIVE STORE) Source: AWM.

The dream of Icarus

Bill’s friend ‘Anzac’ Whiteman was not so fortunate. 3 days later Bill was called into the C.O’s office:

‘Anzac’ Whiteman (left) with 2 other RFC pilots under instruction at Netheravon, September 1916. Photo by P.G. Taylor.

‘I’m sorry to tell you, Taylor, that Whiteman was killed this morning on his first solo. Apparently, he got his nose down and couldn’t pull the machine out …’

It was shocking and sobering news:

I went back to my tent under the pine trees. That damned, lousy instructor! I knew what had happened. He’d sent Anzac solo before he could fly the aeroplane, just as he’d tried to do with me. Obviously Anzac had tried to have a crack at it. I sat on the edge of the bed, thinking. I was eighteen and Death was a newcomer to my thoughts; sickly I knew that he would never leave them while the war lasted. Finally I went for a walk, in the cold, brilliant darkness of the Salisbury Plain. I would have to be alone in the war. There might be passing friends, people around, but the only permanent companion would be Death. Whatever I did I would do it alone.

UNITED KINGDOM. WRECK OF MAURICE FARMAN SHORTHORN SERIAL B1959. (SEE H12729/21 AND /24) (COLLECTION OF LT. H G CORNELL, NO.2 SQUADRON AUSTRALIAN FLYING CORPS (AFC), KIA 1917-12-11 OVER DERNANCOURT. DONATED BY MRS J M CORNELL) Source:AWM

UNITED KINGDOM. WRECK OF MAURICE FARMAN SHORTHORN SERIAL B1959. (SEE H12729/21 AND /24) (COLLECTION OF LT. H G CORNELL, NO.2 SQUADRON AUSTRALIAN FLYING CORPS (AFC), KIA 1917-12-11 OVER DERNANCOURT. DONATED BY MRS J M CORNELL) Source:AWM

Taylor discovered later that his instructor at Netheravon

After doing quite well in France for some months in a machine of poor performance and inadequate armament, his spirit had been broken and he was returned to Home Establishment. There in England, he became a victim of the system and was posted…as an instructor. He was terrified of flying, and his one frantic aim was to get his pupils off solo as soon as possible, so that he wouldn’t have to fly with them.

Taylor and Allport had yet to experience similar stresses. They were enthusiastic, prepared to take risks and push the limits of possibility. To ‘vary the monotony of practice landings,’ Allport decided to see how high the ‘old Maurice Farman’ could fly:

After an hour of persistent climbing, the altimeter showed 8,500 ft. By then the engine checked and spluttered to a stop, with the result that I had a long glide and many spirals to get down, fortunately in a paddock. At this time I expected to be “put on the mat” by the Flight Commander, who was an excitable Frenchman, however, he was most enthusiastic and delighted and endorsed my logbook that I had established a record height for the Squadron.

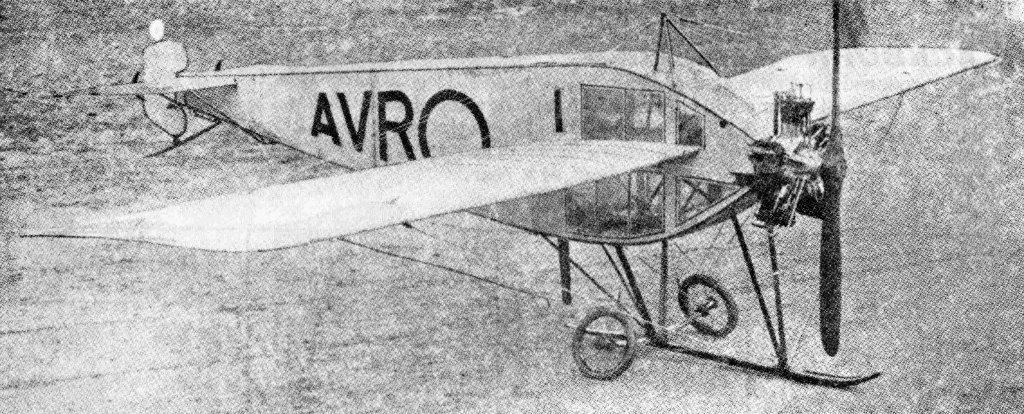

Avro Mono Type F with enclosed cockpit, the type Taylor flew to 7,000ft. Source: ‘Jane’s All The World’s Aircraft 1913’ online https://www.gutenberg.org/files/34815/34815-h/34815-h.htm#Page_37

Avro Mono Type F with enclosed cockpit, the type Taylor flew to 7,000ft. Source: ‘Jane’s All The World’s Aircraft 1913’ online https://www.gutenberg.org/files/34815/34815-h/34815-h.htm#Page_37

As part of his training, Taylor was required to fly to 6,000 ft. He climbed and passed through ‘a wisp of fine weather stratus’ at 4,000 ft.:

What a magnificent world. Around me, a flat white plain stretched to the horizon. Above was the blue dome of the sky. Alone in this infinity, I was the only inhabitant of all space. This was really flying. This was the dream of Icarus.

The photograph shows Lt. P.G. Taylor in France. His face is covered by a home-made leather mask for protection against frostbite (they flew to 17,000 ft. on combat patrols) Source: P.G. Taylor’s autobiography Sopwith Scout 7309.

He felt some difficulty with his breathing. Could he get to 6,000 and still breathe properly?

I had to go up there – that was the height test. 5,400 on the altimeter. I felt dizzy and had to concentrate hard…The Avro [Mono}was climbing very slowly….at 6,000 feet…I was still functioning. My head was singing a bit – was I passing out? …I sat and argued with myself until the altimeter showed 7,000 feet. Then I descended gradually to 4,200, just above the cloud layer, and flew there, my wheels rolling free on the cloud[s]…my heart and my mind 3,000 feet above them.

After picking up his ‘little brown’ Pup with 66 squadron, Taylor began to get a feel for its flying characteristics. Pilots had been told not to loop-the-loop these aircraft. The wings (reportedly) would come off due to a structural weakness. Taylor decided to risk it all. He had to disprove this theory one way or the other…at 6,000 ft he made the decision:

I felt a wild exhilaration and an awareness that perhaps I was pulling the trap to my own gallows. I started to pull the stick back: the nose came up over the horizon…the horizon appeared again, upside down and in the wrong place…The machine started to shudder violently…I thought the wings had gone. Frantically I looked out to each side- they were still there. The wires were screaming, the nose was pointing vertically for the earth. ..she was in an inverted dive. I eased the stick back…the machine came out of her dive…and settled down again in level flight.

He practised a few more times before doing six loops over the aerodrome ‘just showing off, I guess.’

Taylor and the other RFC pilots would need every trick possible. Their ‘Pups’ were out-classed in every department by the German Albatros scouts, except aerial acrobatics.

For conspicuous gallantry…

Bill Taylor and Jack Allport may have had similar experiences but their flight careers diverged after training. Taylor was posted with no. 66 squadron (flying Sopwith ‘Pups’). Jack Allport, on the other hand, flew with 5 and 2 Squadron in Re8’s and Fk8’s.

Both men were later promoted to Captain after being awarded the Military Cross. Their gazetted citations appear below.

Allport’s citation ‘London Gazette’ 19 April, 1918. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30643/supplement/4823

Allport’s citation ‘London Gazette’ 19 April, 1918. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30643/supplement/4823

Taylor’s citation ‘London Gazette’ May 11, 1917 https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30064/supplement/4592

Taylor’s citation ‘London Gazette’ May 11, 1917 https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30064/supplement/4592

Footnotes

1 Both went to Mosman Prep and Shore. Allport lived at “Medbury”, 6 Middle head Rd Mosman, and later in Clifton St. Mosman at “Coombe Cottage” with his wife Edith. Taylor at “Newstead” in Raglan Street.

2 He was on the return journey from Swindon railway station. This was an experience he learned from and was detailed and organised in planning flights as a navigator.

3 Taylor made it back, just. His C.O. approached the landing aeroplane. Taylor braced himself: ‘[but] Instead of getting a blast…he listened to my story and was very decent about it. How much of his kindness was prompted by relief at getting his aeroplane back intact, and how much was approval for my initiative I shall never know. I was simply grateful to be back.’

4 Taylor mentions 2 crashes were in Bristol Scouts near Tern Hill aerodrome. So that’s 1 Avro 504, 1 Be2c, and 2 Bristols. On which of these occasions was Jack Allport part of the crowd of onlookers? Taylor may have had more crashes, or Allport mis-remembered the type as a Be2c. We can only guess.

5 ‘But then we were rejected again, with about 198 other applicants. This was by orders of the G.O.C. of the Australian Forces, but finally the R.F.C., I believe, asked for 32 men from the 3rd Division…’ Gunner Allport was with the 7th Field Artillery.

6 Reference to the night he was returning by train to the Liverpool training camp and was inspired by the article about a raid by Avro’s on the Zeppelin sheds at Cuxhaven. He had wanted to join the Royal Naval Flying Service but was persuaded in England to join the RFC as he was assured they saw more action front line action.

7 Taylor mentions that recruits were encouraged to join the up as Observation Balloonists, which he had no intention of doing.

Bibliography

All quotes are from:

Taylor, P. G. (Patrick Gordon) Sopwith Scout 7309. Cassell, 1968.

Jack Allport’s interview with the Society of WW1 Aero Historians

Follow the P.G. Taylor story in the following articles:

Raglan St to RFC: Mayor P.T. Taylor

Raglan St. to RFC: Bill Taylor’s school days & calling to the skies.

Raglan St. to RFC: Pilgrimage to ‘the silent fields’

Raglan St. to RFC: Bill Taylor: boy mascot company commander avoids the Valentine’s Day mutiny

Fledgling wings: Lt. Taylor inspires Gunner Allport.

Bloody April, 1917: P.G. Taylor survives

Lt. P.G. Taylor & ‘The doomed Rumpler’

Capt. P.G. Taylor, MC; Memories & Memorabilia

Follow the J.M. Allport story in the following articles:

Fledgling wings: Lt. Taylor inspires Gunner Allport.

The high flying (and diving) Capt. Jack Allport.

Capt. Allport, MC: Air war over the Western Front

Capt. J.M. Allport: ‘Aerial Reconnaissance on the Western Front’