Mendinghem Military Cemetery, 2012. Image: Wernervc — Wikimedia Commons

In June 1917 2/Lt. P.G. Taylor received devastating news. In 1960 he made a pilgrimage back to a place long buried in his memories.

Journey through time…

Bill Taylor married his second wife Eileen Joan Broadwood at the Methodist Church, Mosman, on May 10, 1938. Eileen died in 1950. In 1951 Bill re-married. He travelled to France with his wife Joy in 1960.

Driving from Paris to his WW1 aerodrome, Vert Galand, he began to feel a little lost, as though we should not have come; that my wartime life had passed, and should be left undisturbed

Memories came flooding back. The hangars, the fold in the ground where I used to hare down the valley in my Pup, the deckchair under the apple trees where he rested and thought about aerial tactics:

Suddenly I felt as though I had come home.

Somewhat blurry photo of Sopwith Pups lined up at Vert Galand, 1917. Photo by P.G. Taylor

Somewhat blurry photo of Sopwith Pups lined up at Vert Galand, 1917. Photo by P.G. Taylor

The nearby village at Estree Blanche also brought back vivid evocations of the life Bill had known in 1917. At the side of the road, his wife picked flowers. They drove on to find his brother’s grave.

…back to 1917

Men of the 124th Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery manhandling a 9.2 inch howitzer over muddy ground at Pilkem near Ypres, 14 September 1917. Image: Imperial War Museum (Q 3253)

Bill’s older brother, Ken, served with the 184th Royal Garrison Artillery.

By chance, an airman in Bill’s squadron had run into Ken on leave. He was stationed south of Ypres. Bill intended to catch up as soon as possible.

Unfortunately, before he could visit, the 184th was cut off in a German attack. Ken was killed trying to get a message out by motorcycle.

Bill flew across the French countryside:

It was a warm, windless day, very peaceful in the stillness by the new wooden crosses. I found Ken’s grave. He was there; but not, I felt buried in the earth.

Mendinghem cemetery during the war. Image: René Matton

I walked back to Proven, to where my Sopwith Scout waited. I had made my personal pilgrimage to Mendinghem.

I put my hand upon the fabric of the Sopwith. It was warm and smooth. There was a faint smell of burnt Castor oil drifting still from the engine cowl…

Bill remembered how Ken had taught him sailing on the sparkling waters of Pittwater and Sydney harbour. His family was yet to hear the devastating news.

Photo taken at Pittwater. From the right is W. D.M., …sitting on the fence is Patrick Gordon, who preferred to be called ‘Bill’, that’s an unknown, the girl is Norah, their sister, who looks like she’s about 13 or 14 there, the man in the white cap is P. T. Taylor …he was keen on polo, then another unknown and the one on the extreme left is probably Ken.’ Source: Pittwater News Photo and recollection via Don Taylor, son of Bills’ eldest brother.

Photo taken at Pittwater. From the right is W. D.M., …sitting on the fence is Patrick Gordon, who preferred to be called ‘Bill’, that’s an unknown, the girl is Norah, their sister, who looks like she’s about 13 or 14 there, the man in the white cap is P. T. Taylor …he was keen on polo, then another unknown and the one on the extreme left is probably Ken.’ Source: Pittwater News Photo and recollection via Don Taylor, son of Bills’ eldest brother.

1960: Ken, remembered and honoured

On his return pilgrimage with wife Joy, white marble headstones had replaced the wooden crosses at Mendinghem:

Nothing can justify the sacrifice imposed by the madness and greed which are the cause of war, but to find that this sacrifice is still remembered and honoured forty-three years later leaves a cleansing air over the scene of its offering. There at Mendinghem a retired British soldier in a brave Red Beret tended the graves with simple, daily care; and the place itself was filled with quiet tranquillity. It is a good memorial to brave lives. We left our flowers from Estrée Blanche below the clean white headstone, and after taking leave of the Mendinghem guardian, we went our way towards Ypres.

Their journey continued through quiet villages, rebuilt after the war:

… on the way south from Ypres there were more names: Messines, Ploegsteert, Armentieres, Neuve Chapelle, and others; all immortalized by the desperate battles which had been fought there

An aerial view of the Western Front during World War I. Hill of Combres, St. Mihiel Sector, north of Hattonchatel and Vigneulles. Image: San Diego Air and Space Museum Archive

In 1917, the Western Front ran like a gigantic scar through the pockmarked, apocalyptic landscape of mud and obliterated villages. Bill had to reconcile his traumatic memories of 1917 with the tranquil countryside in 1960:

…there was no sadness or morbidity, simply the same serenity we felt at Mendinghem. This was a land charged with valiant endeavour, quiet now with the peace of great sacrifice.

Journey’s end: finding Albert Ball

Bill’s final quest was to find the last resting place of Captain Albert Ball.

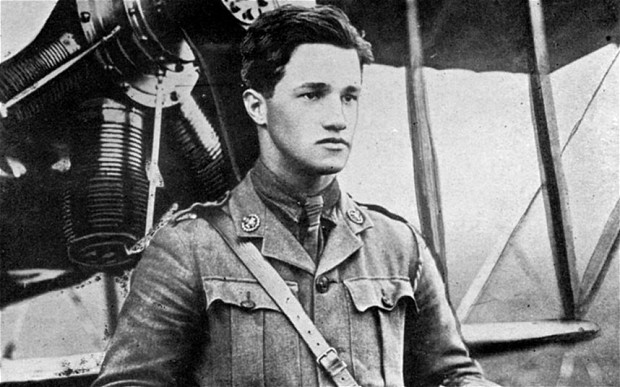

Captain Albert Ball VC. Image: Imperial War Museum (Q 69593)

Captain Albert Ball VC. Image: Imperial War Museum (Q 69593)

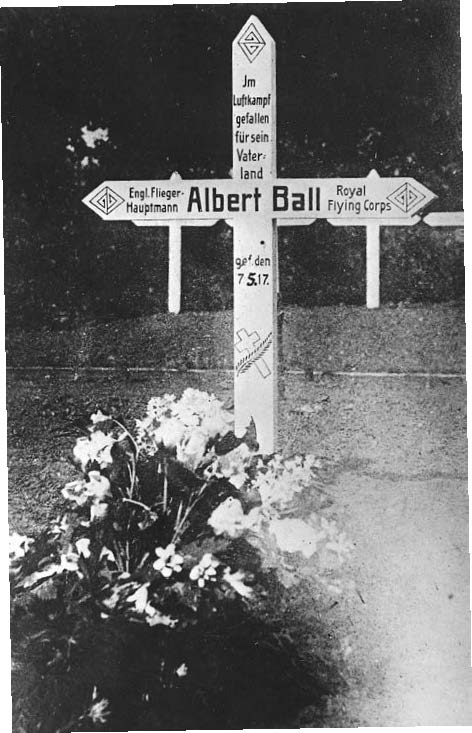

‘Fallen in air combat for his fatherland English pilot Captain Albert Ball’ Wikipedia

To Bill he was a tradition, a simple man who exemplified the highest form of gallantry.

He had become so much a legend in his short career that nobody actually thought of him actually being shot down.

Capt. Ball failed to return from a lone patrol in May, 1917. Days later a German aircraft dropped a message, saying he had been downed by an honourable opponent, and that he was buried at a place called Annoeullin on the German side of the lines, with full military honours.

It wasn’t much to go on, but with a map, Bill and Joy were able to locate the small village after driving along country roads and laneways:

I felt rather ridiculous, arriving out of the blue at this sleepy little village to ask for information about something which happened forty-three years ago. But we were there now and I had to ask somebody; so I stopped the car at a garage where an elderly man was working on a truck. Greeting him as he rose from his work…I explained that we were looking for the pilot who was reported to have been shot down and buried by the Germans in 1917.

His eyes lit up immediately, and he exclaimed, ‘Ah, le Capitaine Ball. Li Tomba ici,’ pointing to the field behind his garage.

We were so excited that we did not wait to ask for details, but followed the directions he then gave us…There in a quiet glade of trees just outside the village we found Ball’s grave…one of a line of other graves all of which were German. Ball had been no enemy, to be put aside in another place. The headstone, erected over his grave after the war by his parents, had a simple inscription, significant of the twenty-year-old boy’s life:

The grave of Albert Ball VC, Royal Flying Corps, German military cemetery, Annoeullin 2015. Image: Paul Reed (@sommecourt)

The grave of Albert Ball VC, Royal Flying Corps, German military cemetery, Annoeullin 2015. Image: Paul Reed (@sommecourt)

Roger Picard, the Taylor’s fiend at the garage, witnessed Albert Ball’s last moments:

“The combat,” he said “started with a few enemy aircraft. Then others took off and he [Ball] was fighting them all, till he was shot down, and then fell in a picquet near a little wood about a hundred metres behind our house.”

Last Flight of Captain Ball. Source: Wikipedia commons

Last Flight of Captain Ball. Source: Wikipedia commons

Bill reflected:

The quiet wood of German crosses, the monument over Ball, moved me deeply. These people, these fields, this country, were a part of me. I thought I had died. I was wrong. I had left part of my younger self there many years before. And now awakened perhaps by my presence, it returned silently to touch me with its strength, and gave me a calmness I have never known before. On the aerodrome, at Vert Galant Farm and Estree Blanche [village] I had found no real memory of aeroplanes, of danger, of the smell of burned castor oil from the rotary engines. The only reality was in ourselves, the living and the dead, and in the silent fields of gently waving barley which stretched away into the distance.

Six years later, on 15 December 1966, Patrick Gordon Taylor died in Queen’s Hospital, Honolulu. His ashes were scattered over his beloved Lion Island. He was survived by his wife Joy, their son and two daughters, and the two daughters from his second marriage to Eileen Broadwood.

A few years before his death he managed to pen his memoirs, dedicating them to Albert Ball and all those who fought in the air over France in the Great War.

Follow the P.G. Taylor story in the following articles:

Raglan St to RFC: Mayor P.T. Taylor

Raglan St. to RFC: Bill Taylor’s school days & calling to the skies.

Raglan St. to RFC: Pilgrimage to ‘the silent fields’

Raglan St. to RFC: Bill Taylor: boy mascot company commander avoids the Valentine’s Day mutiny

Fledgling wings: Lt. Taylor inspires Gunner Allport.

Bloody April 1917: P.G. Taylor survives

Lt. P.G. Taylor & ‘The doomed Rumpler’

Capt. P.G. Taylor, MC; Memories & Memorabilia

Bibliography

All quotes from: P.G. Taylors book:Sopwith Scout 7309 London : Cassell, 1968