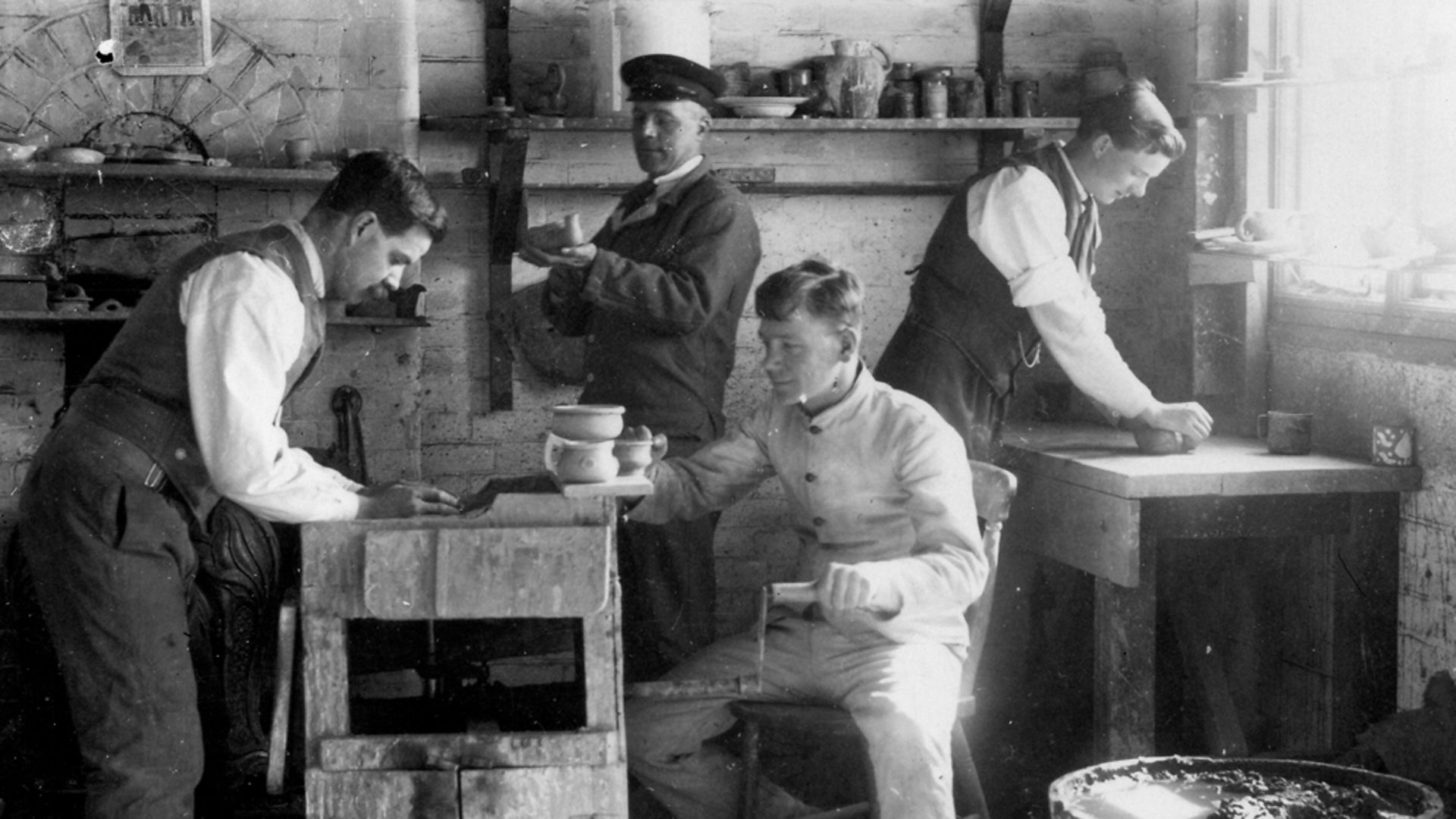

Shell-shocked soldiers to whom Preston taught basket-weaving at the Seale-Hayne Neurological Military Hospital, Devonshire (UK). Preston is just out of camera to the right, but her black Scottish Terrier ‘Little Jim” can be seen sitting next to her in the bottom right-hand corner.

Shell-shocked soldiers to whom Preston taught basket-weaving at the Seale-Hayne Neurological Military Hospital, Devonshire (UK). Preston is just out of camera to the right, but her black Scottish Terrier ‘Little Jim” can be seen sitting next to her in the bottom right-hand corner.

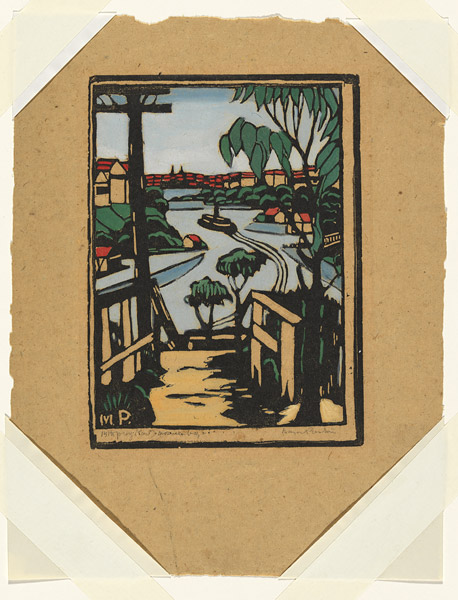

After the 1914-18 war, Margaret Preston lived and created artworks in Mosman.

During the war, Margaret and friend Gladys Reynell got the chance to help rebuild shattered lives.

More than one vision.

Margaret Rose Preston (nee. McPherson) was born on 29 April 1875. She began training as a traditional artist in Sydney at age 9. In 1893 she enrolled at the National Gallery’s art school in Melbourne, under Frederick McCubbin.

Margaret McPherson in her Adelaide studio c1909 photograph from the State Library of SA

Margaret McPherson in her Adelaide studio c1909 photograph from the State Library of SA

McCubbin had a close association with Tom Roberts and the Heidelburg School. Roberts and other Australian Impressionists set up and painted at Camp Curlew.

Margaret McPherson left Australia in 1904. She travelled with hometown friend and fellow artist Gladys Reynell. They absorbed European culture and studied contemporary art trends.

Ms McPherson’s antipodean eyes were opened to Post-Impressionism;

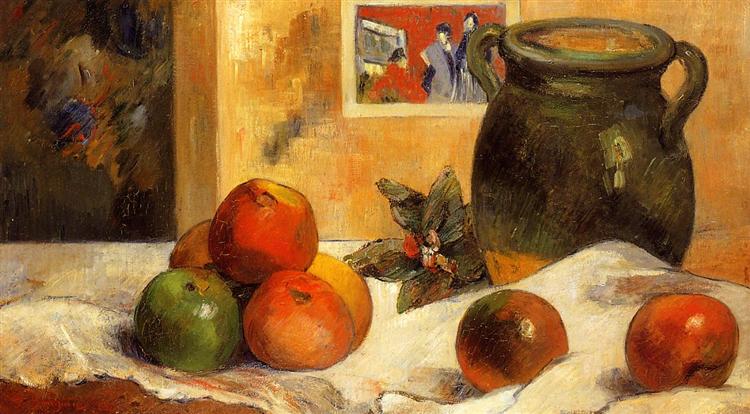

Cézanne, Matisse, Kandinsky, Rouault, Picasso and Paul Gaugin influenced her work. She admired Gaugin in particular, describing him as a ‘magnificent colourist’.1

Still life with Japanese print; Paul Gauguin, 1888; France; Style: Japonism; Period: Breton period; Media: oil, canvas

Still life with Japanese print; Paul Gauguin, 1888; France; Style: Japonism; Period: Breton period; Media: oil, canvas

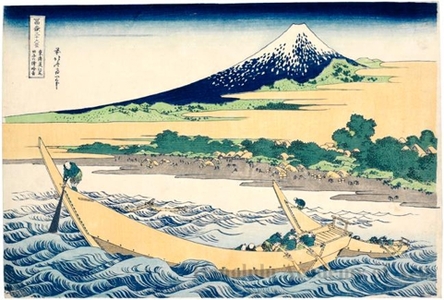

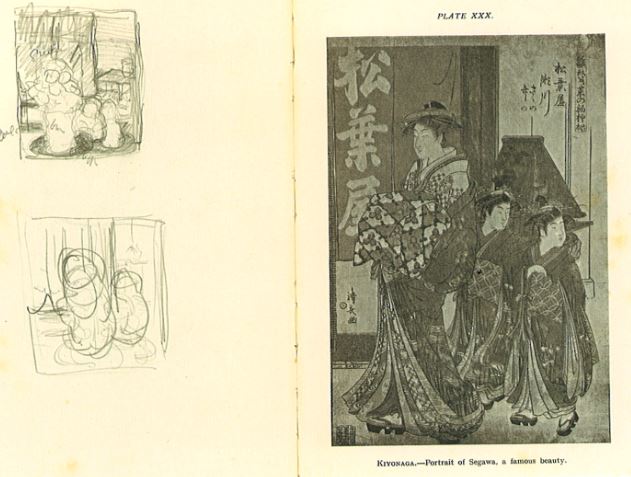

Like so many artists and theorists of the time, she developed fascination for Japonisme. She studied decorative arts and traditional design at the Musée Guimet, the Louvre, and the Victoria & Albert Museums. Of particular interest to her were the woodblock Ukiyo-e masterworks.

In her own words she

learnt slowly that there is more than one vision in art.2

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji: Tago Bay Near Ejiri on the Tokaido

Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji: Tago Bay Near Ejiri on the Tokaido

Margaret and Gladys, based in England after the invasion of France, continued to practice, study and teach.

In 1915 Margaret, Gladys and 21 students went on a field trip to Ireland. She painted Still life with teapot and Daisies by the sea at Bunmahon, County Waterford. Ukiyo-e influences are present in the placement of objects and spacial flattening.

Still life with teapot and daisies (1915), oil on cardboard 44.3 × 51.2 cm Gift of the W.G. Preston Estate 1977 to Art Gallery of NSW

Still life with teapot and daisies (1915), oil on cardboard 44.3 × 51.2 cm Gift of the W.G. Preston Estate 1977 to Art Gallery of NSW

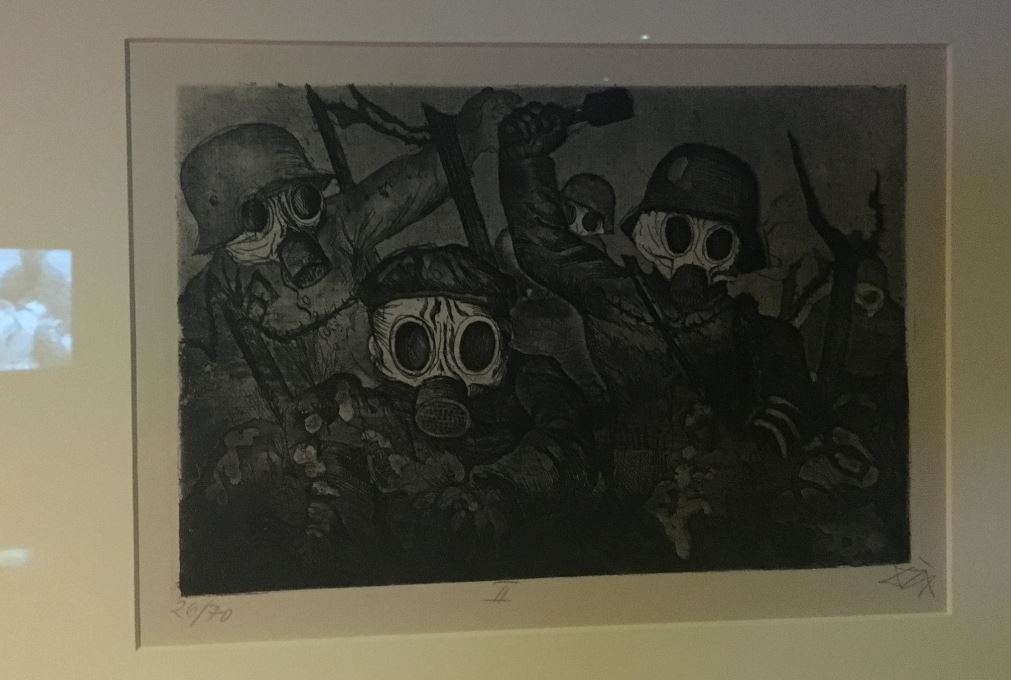

The painting’s warm pastel tones seem to defy the storm clouds of industrialized Armageddon in Europe. The light, cheery seaside setting completely contrasts with Otto Dix’s nightmarish depictions.

U-boats lurking off the coast and the sinking of the Lusitania confined Margaret and Gladys to England. In 1916 they enrolled at the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts. Here they studied pottery, basket weaving, printmaking, fabric printing and dyeing.

Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London. Est.1898

Camberwell College of Arts, University of the Arts London. Est.1898

‘Beaker 1917’ made by Gladys Reynell depicting Margaret’s dog ‘Little Jim’ and neighborhood cat. Carew Reynell’s widow sent Gladys a gift of local S.A. clay for her pottery.

‘Beaker 1917’ made by Gladys Reynell depicting Margaret’s dog ‘Little Jim’ and neighborhood cat. Carew Reynell’s widow sent Gladys a gift of local S.A. clay for her pottery.

The Reynells

Gladys’ family were doing their bit.

Carew Reynell manager of ‘Reynella’ winery3, enlisted as an officer with the 9th Australian Light Horse. The family was emotionally devastated after his death at Gallipoli.

HILL 60, GALLIPOLI. 27/08/15. Commanding Officer 9TH Aust. LHR Ltn.-Col. Carew Reynell chatting (hunting lice in his clothing). He was killed the next day, 28/08/15. Source: AWM

HILL 60, GALLIPOLI. 27/08/15. Commanding Officer 9TH Aust. LHR Ltn.-Col. Carew Reynell chatting (hunting lice in his clothing). He was killed the next day, 28/08/15. Source: AWM

Walter Rupert Reynell, Rhodes Scholar and Neurologist worked with shell-shocked soldiers. Gladys’s younger sister, Emily was a volunteer nurse.

Rupert had written to their father in 1915:

Gladys’ attitude is testing my comprehension4

He invited Gladys and Margaret to become more useful to the war effort. He wrote in 1918:

Gladys and Margaret McPherson[are] coming to teach pottery to the patients here..”5

Seale Hayne: the Quadrangle. The buildings date from 1909-14. After years of uncertainty, the Dame Hannah Rogers Trust purchased the main buildings and part of the estate in December 2009, thus at least preserving an educational function at the heart of the old campus. There are now a tea room and retail outlets for craft and artworks. Source: http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/2015305

Casting out the demons

Thousands of soldiers were sent back to Britain with shell-shock. Dr. William Halse Rivers advocated a humane treatment program based on ‘talking cures’ and educating the patient. A far more enlightened approach than the electric shock ‘therapies’ administered at other facilities.

Siegfried Sassoon wrote the poem Survivors, whilst being treated at Craiglockhart hospital by Dr Rivers. Sassoon befriended fellow patient and poet Wilfred Owen. (Owen, sadly, was killed one week before the war ended.)

‘Survivors’ (1917) from Counter-Attack and Other Poems

NO doubt they’ll soon get well; the shock and strain

Have caused their stammering, disconnected talk.

Of course, they’re ‘longing to go out again,’—

These boys with old, scared faces, learning to walk.

They’ll soon forget their haunted nights; their cowed

Subjection to the ghosts of friends who died,—

Their dreams that drip with murder; and they’ll be proud

Of glorious war that shatter’d all their pride…

Men who went out to battle, grim and glad;

Children, with eyes that hate you, broken and mad.

Dr. Arthur Hurst, [Dr. Reynell’s supervisor] used both hypnosis and electric shock treatment, but gave them up for alternative techniques. In the words of historian Taylor Dowling:

He believed in creating a highly charged and positive atmosphere in which hysterical patients would see recovery occurring in others around them.

Dr Hurst was a great showman and made countless claims as to his ability to cure the symptoms of hysteria. The expectation that a patient would receive a miracle cure was drummed into him from the moment he arrived at the hospital…Preparation might take several days and the nurses would have a vital role to play in explaining to the patient beforehand how wonderful the effects of the treatment would be. On the day of the treatment, the build-up to meeting the doctor turned the encounter into almost a religious experience.

When the patient finally came before Hurst. The treatment was by suggestion. Hurst forcibly commanded him to get better and applied some physiotherapy involving powerful manipulation of the arms and legs until the patient was completely relaxed and the power to perform physical movements had been restored. In this process ‘the personality of the medical officer is always of greater importance than the particular method.’6

At Seale Hayne, a series of films were made to record the success of Hurst’s techniques.

These short clips capture some of the sad and freakish behaviour of shell shock victims, recording tragic scenes of men who cannot walk and who roll about on the floor, who shake uncontrollably, who leap under the bed at the mere mention of the word ‘bomb’. The purpose of the films was to show victims before and after the treatment with Hurst. Certainly, the patients on film appear to be cured…however, Hurst’s many critics were not convinced that by removing the symptoms of hysteria was the same as curing the source of the problem.7

The film includes men weaving baskets at Seale Hayne:

Crafts that aid

Margaret and Gladys arrived at Seale-Hayne Hospital in August 1918. Margaret remembered8:

25-35 men would arrive every few weeks to the Hospital. These the various doctors would bring down to the shed known as the Pottery. The work was under the strict supervision.

They were given instruction in weaving, pottery or other crafts depending on their condition:

This was to aid them to regain confidence in their own abilities as well as to interest them while they were waiting for their cures.

Some of the shell-shocked soldiers to whom Preston taught basket-weaving at the Seale-Hayne Neurological Military Hospital, Devonshire (UK). Preston is just out of camera to the right, but her black Scottish Terrier ‘Little Jim” can be seen sitting next to her in the bottom right-hand corner.

Some of the shell-shocked soldiers to whom Preston taught basket-weaving at the Seale-Hayne Neurological Military Hospital, Devonshire (UK). Preston is just out of camera to the right, but her black Scottish Terrier ‘Little Jim” can be seen sitting next to her in the bottom right-hand corner.

Basket weaving was recognised as the most useful therapy for twisted and stiffened hands. The teachers improvised when weaving materials ran out. Any branches strong and supple enough would do:

When these baskets were sold to the local housewives of Newton Abbott (the nearest town), some of the women complained that the baskets “started to shoot” on shopping expeditions, and were a little conspicuous; but it was pointed out to them that these were really “war baskets,” so no money had to be given back….

Some men later earned a living making fish and clothes baskets, ‘which take strong hands and careful work’

Preston noted that pottery work was ‘of the greatest assistance’ to men with shell shock:

This craft helped cure in many ways. For one thing, it gave an easy and interesting occupation. For another, it restored confidence, when the patient found that he could make things that his doctor could not. Again, it gave healthy exercise and allowed the brain to work out original ideas and put them into practice. Perhaps the great thing was, that, at the end of the labour, the patient possessed an object that even the doctors wanted, and that he could raise money on if he so wished.

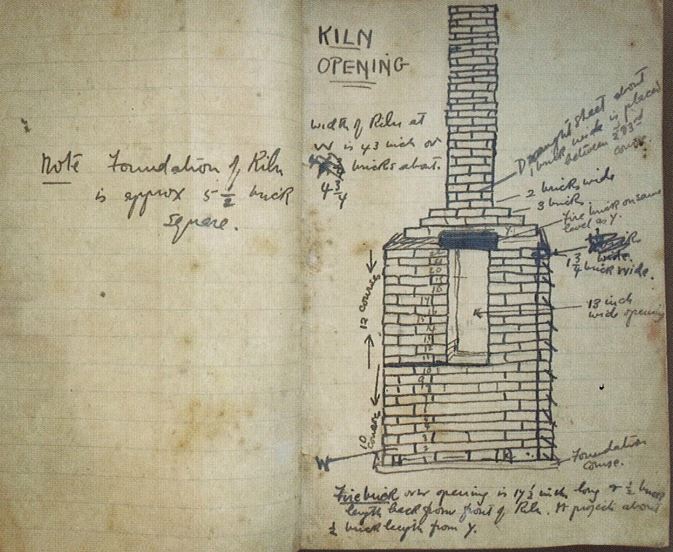

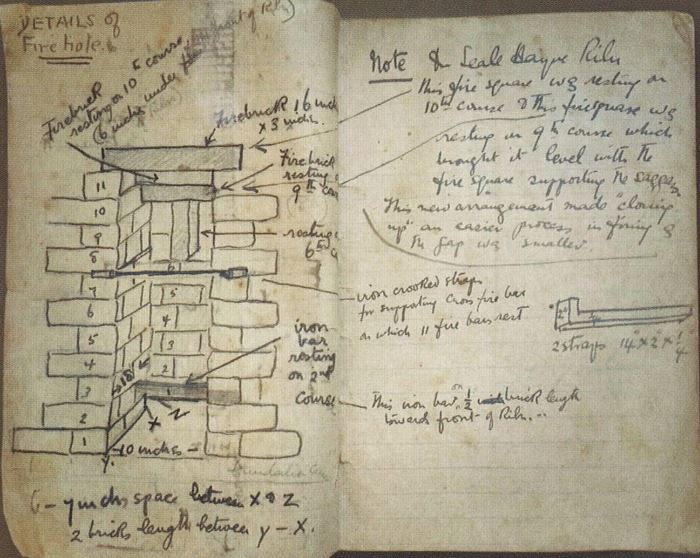

Margaret and Gladys had to design and supervise the making of a kiln:

It was found that amongst the patients were bricklayers, who were capable, under strict supervision, of laying the bricks. This was done from a simple plan of a small brick kiln, of the kind generally used as an experimental one for brick factories.

Drawings of kiln construction from McPherson’s sketchbook 1917. Margret Preston Papers. Art Gallery NSW.

Drawings of kiln construction from McPherson’s sketchbook 1917. Margret Preston Papers. Art Gallery NSW.

Clay was excavated from the local area. It was put into tubs of water and hand-mixed by patients the next day. Therapeutic mud-kneading did not work for one patient:

Memory goes back to one poor “Tommy” who had decided that his hands could not move. When they were gently “pushed” into this mud, he quickly decided to pull them out and use them on the “pusher,” who was myself. The doctor rushed to the rescue and took away a soldier who had been partly cured of a difficult complex.

A basic turning wheel was made:

One soldier would turn the handle, while another threw on the wheel. It would hardly seem possible that turning a wheel would start a cure in a case of badly shaking nerves, but this happened.

Preston notes that for those did not like throwing clay on the wheel:

They were shown how to make objects by winding sausages of clay together. Some of these men produced fantastic animals and grim creatures that would have turned Dali green with envy.

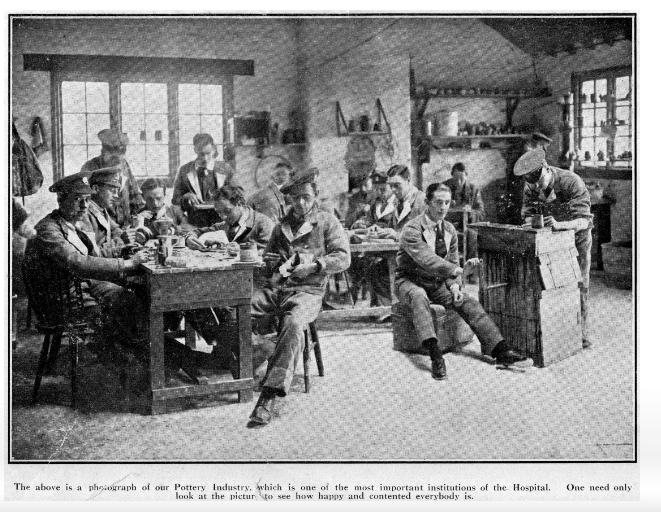

Pottery making at Seale Hayne. Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0297rc8

Pottery making at Seale Hayne. Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p0297rc8

She also notes that other crafts interested the men. Simple dyeing was one:

This meant long walks on the moors, looking for plants that would give dyes… These were brought back to the shed, cooked in jam tins, and later fixed ..Thus the dye would not come out of the cloth when it was washed.

Dyeing was used in conjunction with batik work. ‘Cushion covers were generally the greatest extent of our ambitions.’

Simple wood-cut prints ‘helped things along.’:

everything that could be made to do was used. Cigar-box lids, old pieces of furniture that could be cut into shapes; any wood that had a fine grain.

Paint would be rubbed on an old tray with a photographer’s squeegee, and then over the upstanding design of the wood. A piece of dampened paper would be put on this, and rolled over with a clean roller. The paper was taken off, and the results shown around for criticism.

Men basket weaving at Seale Hayne Source: Owen Davies Twitter feed

Men basket weaving at Seale Hayne Source: Owen Davies Twitter feed

Monotypes and Stencilling were also popular:

as they caused no excessive expenditure of energy. … Many made Christmas Cards this way. The cards were, of course, unique, as it is only possible to get one copy by this method.

All the crafts are better than that horrible work known as crewel work. The most pathetic thing was to see a big wounded soldier plugging away in crewels at the motto, “God Bless our Happy Home,” which was often to be seen in the war hospitals.

Doctors and guests visited and took an interest in the patient’s handiwork. The men were reluctant to part with their creations, which ended up in houses and workplaces:

remind[ing] their owners of the pottery shed at Seale Hayne Hospital on the Devon moors.

Photograph from paper produced at Seale-Hayner Hospital. Source: http://longstreet.typepad.com/thesciencebookstore/2015/10/ghost_train.html Preston notes visitors to the Hospital included author John Galsworthy, who edited ‘a kind of shell-shock paper.’

Photograph from paper produced at Seale-Hayner Hospital. Source: http://longstreet.typepad.com/thesciencebookstore/2015/10/ghost_train.html Preston notes visitors to the Hospital included author John Galsworthy, who edited ‘a kind of shell-shock paper.’

Safe harbour

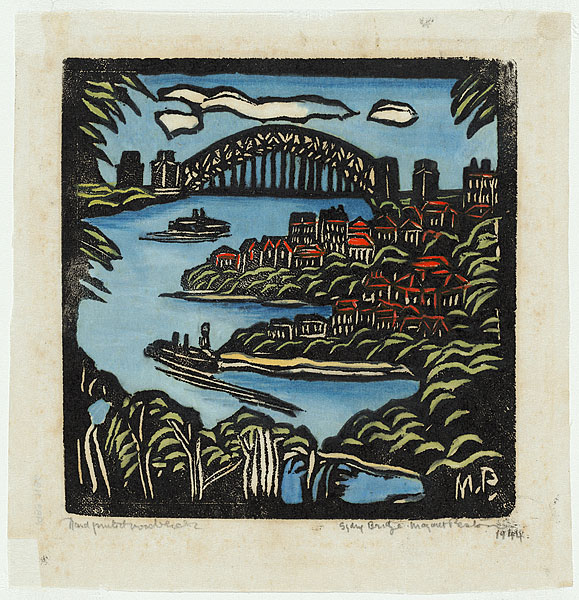

‘Mosman Bay’ 1927, woodcut, printed in black ink, hand coloured with gouache on thin ivory laid tissue. Source: National Gallery, NGA 76.937

‘Mosman Bay’ 1927, woodcut, printed in black ink, hand coloured with gouache on thin ivory laid tissue. Source: National Gallery, NGA 76.937

William George Preston was a 2nd Lieutenant in the Australian Artillery. He met Margaret McPherson in London and proposed to her en route to Australia.

Margaret and Gladys held a joint pottery exhibition in Adelaide in September 1919 which included pottery from the Seale Hayne Hospital.

Margaret married George Preston on the 31/12/1919 in Adelaide. The reception was held at ‘Reynella’, the Reynell family home.

Margaret and George moved to Sydney and settled into ‘Glenorie’, a bayside flat in Musgrave St., Mosman. Here her artistic endeavours continued. The move effectively ended her creative partnership with Gladys. In George’s words, he’d ‘broken up the ‘twosome.’9

The Prestons at home in Mosman.

The Prestons at home in Mosman.

George resumed his position as manager of Dalton Bros. Ltd. Later at Anthony Hordern &Sons his overseas imports included Japanese textiles. The Prestons moved to ‘Preston’, 11 Park Ave, Mosman in 1922 where they lived for 10 years.

Later they lived as long-term residents at the Mosman Hotel. Margaret took over the guests’ sunroom, using it as her personal studio, and ‘tended to treat staff as personal servants.’10

Mosman Bay

Mosman Bay

Through a Japanese sieve.

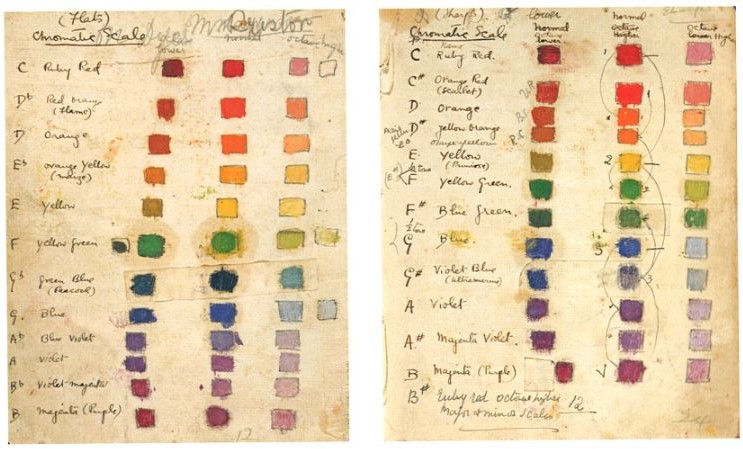

Her work in the ’20s and 30’s incorporated colour theories developed during the war years:

[Preston] systematically compiled subsets of colours based on all the possible major and minor scales in small squares of oil paint. These subsets correspond to traditional Western scales but Preston also developed ‘Japanese schemes’.11

‘It is clear that Preston’s references to Japanese schemes and their numbered books relate to the classified collection of textile designs “Shikiman Ruisan”, published by Teikoko Hakubutsan (Imperial Museum), Tokyo, 1892. 6 of the 10 volumes were bequeathed by William Preston to the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1963.’ Source: https://aiccm.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/BPG2006/AICCM_B&P2006_Peel_p18-35.pdf

‘It is clear that Preston’s references to Japanese schemes and their numbered books relate to the classified collection of textile designs “Shikiman Ruisan”, published by Teikoko Hakubutsan (Imperial Museum), Tokyo, 1892. 6 of the 10 volumes were bequeathed by William Preston to the Art Gallery of New South Wales in 1963.’ Source: https://aiccm.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/BPG2006/AICCM_B&P2006_Peel_p18-35.pdf

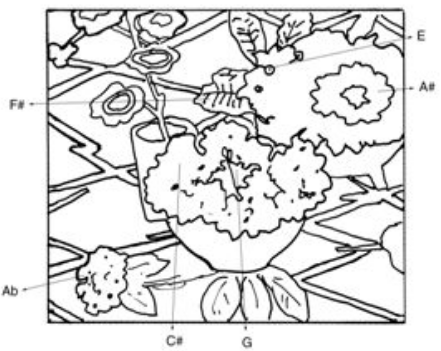

Diagram of’ ‘Flowers, 1917’ showing relationship of chromatic scheme with pigments. from: https://aiccm.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/BPG2006/AICCM_B&P2006_Peel_p18-35.pdf

Diagram of’ ‘Flowers, 1917’ showing relationship of chromatic scheme with pigments. from: https://aiccm.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/BPG2006/AICCM_B&P2006_Peel_p18-35.pdf

‘Flowers, 1917’ oil on board oil on board 46.0 h x 54.7 w cm National Gallery of Australia. Note the use of ‘Japanese’ colours and corresponding scales applied to final picture.

‘Flowers, 1917’ oil on board oil on board 46.0 h x 54.7 w cm National Gallery of Australia. Note the use of ‘Japanese’ colours and corresponding scales applied to final picture.

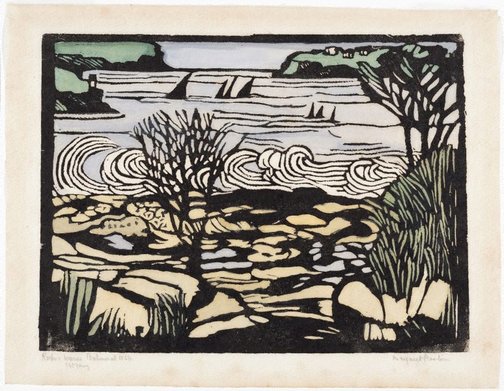

By the 20’s her style was well defined: flat planes of decorative colour; linear definition of form; diagonal structure and expanded space (encouraging viewers to use their ‘mind’s eye’.)12

Still Life, 1925 is a good example of Preston’s evolution from academic realism to oriental inspired modernism.

Still Life, 1925 National Gallery of Australia. Oil on canvas

Still Life, 1925 National Gallery of Australia. Oil on canvas

During the ’20s,

Preston put Sydney’s urban environment through a Japanese sieve..and contributed to the continuing relevance of Japonisme in 1920’s Australian design.13

Preston’s adaptation of Japanese prints in Edward F Strange’s ‘Japanese colour prints’, 2nd ed., 1908. AGNSW Archive Photographer Chilin Gien for the AGNSW.

Preston’s adaptation of Japanese prints in Edward F Strange’s ‘Japanese colour prints’, 2nd ed., 1908. AGNSW Archive Photographer Chilin Gien for the AGNSW.

Rocks and waves, Balmoral, NSW c1929 woodcut, black ink hand coloured with gouache on thin cream laid Japanese tissue 1st proof from unknown edition, hand coloured, purchased by AGNSW 1976. Source: https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/141.1976/

Rocks and waves, Balmoral, NSW c1929 woodcut, black ink hand coloured with gouache on thin cream laid Japanese tissue 1st proof from unknown edition, hand coloured, purchased by AGNSW 1976. Source: https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/141.1976/

Preston’s sense of place was also represented through the urban landscape.

In moving closer to the traditions and intimacies of Hiroshige and Hokusai produced a set of Sydney-Australian views depicting the emphatic modernity of the harbour through its increasing mechanisation.15

Mosman Bay. 26 March 1920. Woodcut, printed in black ink, from one block; hand-coloured thin Japanese paper. Source: National Gallery. NGA 87.20

Mosman Bay. 26 March 1920. Woodcut, printed in black ink, from one block; hand-coloured thin Japanese paper. Source: National Gallery. NGA 87.20

Works such as Circular Quay and Sydney Bridge represent this modernity and mechanization, as do the geometric forms of _*Spit Bridge*_(1929)

During her Mosman period, Preston also produced works such as Edward’s Beach, Balmoral (1929) and Red Cross Fete (1920). These idyllic, intimate visual vignettes are glimpses into inner-harbour life in the 1920s. They also have a timeless quality, like the foreshores themselves…

Red Cross Fete, Mosman, 1920. woodcut, printed in black ink, from one block; hand-coloured thin Japanese tissue paper mounted on cardboard NGA 1978.761

Red Cross Fete, Mosman, 1920. woodcut, printed in black ink, from one block; hand-coloured thin Japanese tissue paper mounted on cardboard NGA 1978.761

Don’t ask questions!

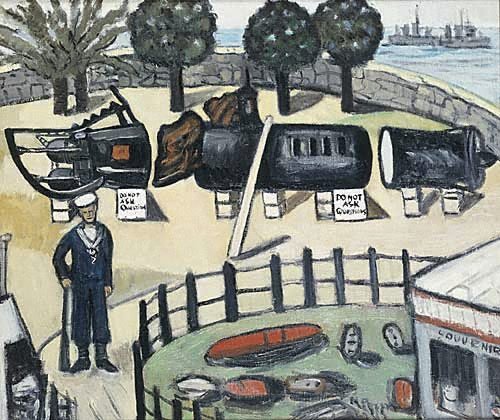

Prestons later works ventured beyond her main subject matter of still life and landscape.

Two examples are Taronga Zoo and Japanese submarine exhibition

‘Japanese submarine exhibition’, 1942, oil on canvas 43.2 × 50.8 cm. Source: Art Gallery NSW, gift of Mr W.G. Preston the artist’s widower 1967

‘Japanese submarine exhibition’, 1942, oil on canvas 43.2 × 50.8 cm. Source: Art Gallery NSW, gift of Mr W.G. Preston the artist’s widower 1967

Japanese submarine exhibition depicts the wreckage of the mini-sub recovered from Taylor’s Bay.

In the picture, Australian navy surveillance boats patrol the harbour. A sailor stands watch over the exhibit and wreckage strewn about in front of a ‘Souvenir’ shed. ‘Souvenir-ing’ can be read as a general comment on, or metaphor about, the dirty business of war profiteering..’16

Signs warn the onlooker: ‘Do not ask questions’

‘ Do not ask questions’ (a command recognised as antithetical to Preston’s credo) embod[ies] the cynicism with which Preston greeted the aftermath of the submarine tragedy.17

although Preston left no explanation of her wartime pictures, her correspondence and 1943 articles indicate her concerns. Preston was one of the few Australians with first-hand experience of Japanese culture, an appreciation deepened by her 1934 travels there. Hence she could not share the vehemence of Australian propagandists..18

She and George were disturbed by the internment of acquaintances and the denouncement of neighbour Ken Prior, as a Japanese agent.19 Her concerns about censorship and cultural xenophobia came through in Tank traps and General Post Office.

Tank traps exploited the design of massive pyramidal barriers on her local beaches of Mosman and Narrabeen, to portray the country subsumed in the machinery of war.. [and the] metaphorical closing down of the country to the possibility of involvement with Asia..20

Tank traps. Oil on canvas Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery Gift of Dr and Mrs C. B. Christesen, 1978 from https://chasspain.wordpress.com/2015/05/11/good-art-is-a-womans-reflection-on-war/

Tank traps. Oil on canvas Mornington Peninsula Regional Gallery Gift of Dr and Mrs C. B. Christesen, 1978 from https://chasspain.wordpress.com/2015/05/11/good-art-is-a-womans-reflection-on-war/

The General Post Office on George Street, Sydney, boarded up and sandbagged, is ‘a metaphor for censorship at that hub of communications.’21 The viewer is drawn to a recruitment poster in the middle of the picture, and then Martin Place Cenotaph,

…as a reminder of the slaughtered in the Great War, during which she had nurtured the wounded.22

When looking at the picture one can almost see life and death fast-tracked. The recruit passes through the black doors of the recruitment office, then is remembered at the Cenotaph;

…a memorial she long despised for its ‘realism without offering conviction of grief or anything else but tailor’s dummies’.23

The drapers shop to the right of the Post Office on Rowe St. references the tailors dummies.

General Post Office. Oil on canvas Source:https://chasspain.wordpress.com/2015/05/11/good-art-is-a-womans-reflection-on-war/

General Post Office. Oil on canvas Source:https://chasspain.wordpress.com/2015/05/11/good-art-is-a-womans-reflection-on-war/

The colour and content of Preston’s later works have an iconic Australian or indigenous feel. The style she developed during her early years, however persisted on

Most of her significant works can be viewed online at the Art Gallery NSW, National Gallery and National Gallery of Victoria.

The Mosman Art Gallery also holds some of Preston’s works. Its exhibition Tokkotai: Contemporary Australian and Japanese Artists on war and the Battle of Sydney Harbour commemorated the 75th anniversary of the Midget Sub sinking.

Sydney Bridge (1944 Woodcut), printed in black ink, from one block; hand-coloured in gouache cream Japanese-style paper. Bequest of Alan Queale 1982

Sydney Bridge (1944 Woodcut), printed in black ink, from one block; hand-coloured in gouache cream Japanese-style paper. Bequest of Alan Queale 1982

NGA 83.1136

Footnotes

1 Harding, Lesley Margaret Preston: recipes for food and art [Carlton, Victoria] The Miegunyah Press, an imprint of Melbourne University Publishing, 2016. p.156

2 Preston, Margaret From Eggs to Electrolux Art in Australia; No 22, Dec. 1927, p.25.

3 Carew enlisted with his occupation as Vigneron

4 Margaret Preston: Still life with teapot and daisies Art Gallery NSW retrieved online 21/02/18 https://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/works/192.1977/

5 Edwards, Deborah, Peel, Rosemary and Mimmocchi, Denise Margaret Preston (New ed). Thames & Hudson, Fishermans Bend, Vic, 2010. p1917

6 Dowling, Taylor Breakdown: The crisis of shell-shock on the Somme, 1916 Little, Brown Book Group; London, 2016

7 Ibid

8 All quotes on Seale Hayne in The arts that heal are from Margaret Preston’s article: Preston, ‘Crafts That Aid’ Art in Australia 3rd Series No.77 Nov. 15, 1939

9 Harding, Lesley Margaret Preston: recipes for food and art [Carlton, Victoria] The Miegunyah Press, an imprint of Melbourne University Publishing, 2016. p.61

10 Huxley, John The pot that nearly spoilt a moment in art retrieved online smh.com.au http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2002/09/20/1032054960256.html 14/02/18

11 Peel, Rose Margaret Preston: A material girl explained retrieved online 14/02/18 https://aiccm.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/BPG2006/AICCM_B&P2006_Peel_p18-35.pdf

12 Ibid.

13 Edwards, Deborah, Peel, Rosemary and Mimmocchi, Denise Margaret Preston (New ed). Thames & Hudson, Fishermans Bend, Vic, 2010. p.82

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid. McQueen, Humphrey p182.

17 Ibid.

18 Edwards, Deborah, Peel, Rosemary and Mimmocchi, Denise Margaret Preston 2010. p.179

19 Ibid. p.184

20 Ibid. McQueen, p.182.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid. p.178 quote of Preston from ‘Meccano as an ideal’, Manuscripts, no 2, 1932 p. 90-91

Bibliography

Butel, Elizabeth Margaret Preston (New ed). Royal Exchange, NSW ETT Imprint, 2015

Butler, Roger, Preston, Margaret, 1875-1963 and National Gallery of Australia The prints of Margaret Preston : a catalogue raisonné (Rev. and enlarged ed). National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2005.

Edwards, Deborah, Peel, Rosemary and Mimmocchi, Denise Margaret Preston (New ed). Thames & Hudson, Fishermans Bend, Vic, 2010.

Harding, Lesley Margaret Preston: recipes for food and art [Carlton, Victoria] The Miegunyah Press, and imprint of Melbourne University Publishing, 2016.

Peel, Rose Margaret Preston: A material girl explained retrieved online 14/02/18 https://aiccm.org.au/sites/default/files/docs/BPG2006/AICCM_B&P2006_Peel_p18-35.pdf

All quotes on Seale Hayne in The arts that heal are from Margaret Preston’s article:

‘Crafts That Aid’ Art in Australia 3rd Series No.77 Nov. 15, 1939, copied in full below:Crafts That Aid

This is an article from Art in Australia, November 15th, 1939 entitled Crafts That Aid. Preston notes that it is ‘partly reminiscent and partly it deals with the immediate future.’ (The Second World War had just started.) Having experienced the effects of war she realised that ‘the moment to prepare for such work’ had, unfortunately, come again.

Mrs. Preston is one of Australia’s leading artists, and she can talk interestingly about the crafts she practises. A few months ago, under the auspices of the Carnegie Institute, she gave a series of lectures at the National Art Gallery of New South Wales. These proved highly genial and entertaining. The subject-matter included many aspects of art, such as the preservation of oil paintings and the best way of printing woodcuts. Mrs. Preston touched briefly then on the use of various crafts in war-time. The present article amplifies those remarks.

THIS article is a personal one. It is partly reminiscent and partly it deals with the immediate future.

In 1916, British shell-shocked and injured soldiers started pouring into England. This necessitated hospitals that were fitted to deal with their maladies. Many cases, such as those with shock to the nerves and with injured limbs had long intervals between the various times when they were seen by the doctors and by the administration. This circumstance demanded the services of persons who were able to interest the men, and to aid the doctors in ways that did not come under the heading of “nursing.” Some of this work took the form of handicrafts.

My own experience was gained in a shell-shock hospital situated on Dartmoor, England. The building had been an agricultural college, and it was requisitioned by the Government for the use of soldiers suffering from nerve trouble. This was the main object of the hospital, but there were also cases of twisted hands and stiffened limbs that had to be treated. The hospital was for the rank and file, and not for officers.

The men would arrive in fortnightly batches from the war areas. My work was to take from twenty-five to thirty men every two or three weeks. These the various doctors would bring down to the shed known as the Pottery. This outhouse was originally the dairy of the agricultural college. The work was under the strict supervision of the doctors. It consisted of basket-making for twisted and stiffened hands; of pottery for the shell-shocked men. This was to aid them to regain confidence in their own abilities as well as to interest them while they were waiting for their cures. There were others who came to the shed with complaints that allowed them only to amuse themselves. These did monotypes, batik, and other handicrafts.

Perhaps the most valuable of them all was basket-making. This simple craft has the greatest right of all the handicrafts to the name, as it is about the only one that cannot be carried on by machinery. The great help that basket-making gives to twisted hands and stiff arms is now acknowledged by doctors who have worked in war hospitals. Pulling of the canes and holding and separating the rods used muscles and fingers that had become stiff and hard. Another thing that helped was the simplicity of the craft. It did not worry tired brains, and took very little concentration to obtain a good result. These facts place basket-making well on the way to being one of the most useful of the handicrafts for war-time work.

For those who know nothing of this art, a few explanations and illustrations might be of interest. The materials are inexpensive and substitutes can be easily procured. When cane gave out at the hospital, young rose shoots, raffia, and Paddy’s lucerne were used. In fact, any branches that were strong and supple enough to twist were made into

baskets. When these baskets were sold to the local housewives of Newton Abbott (the nearest town), some of the women complained that the baskets “started to shoot” on shopping expeditions, and were a little conspicuous; but it was pointed out to them that these were really “war baskets,” so no money had to be given back

As regards the materials for this work, only a few tools are necessary — a basket-maker’s bodkin, a pair of sharp shears, a picking knife, and a basket-maker’s iron for knocking the cane together. For a simple basket, two kinds of rods are employed. Some of these are young and pliable. The others are older branches, known as “sticks.” For larger baskets, stronger canes and a different method are used, but it can be seen how the hands are used in manipulating the sticks. The pulling and stretching of the fingers all help in the recovery of lost suppleness. It is suggested here that lessons could be taken from the blind, so that when a time comes there will be found persons who will be able to help when necessary. At the hospital on Dartmoor, some of the men went on to advanced lessons in this craft. They are now earning their living making fish and clothes baskets, which take strong hands and careful work.

Next to basket-making, pottery work was of the greatest assistance. This craft helped cure in many ways. For one thing, it gave an easy and interesting occupation. For another, it restored confidence, when the patient found that he could make things that his doctor could not. Again, it gave healthy exercise and allowed the brain to work out original ideas and put them into practice. Perhaps the great thing was, that, at the end of the labour, the patient possessed an object that even the doctors wanted, and that he could raise money on if he so wished. The method of making pottery by these shell-shocked men was simple in the extreme and had no connection with public money making. As the hospital was out on the moors, there was no gas or electricity for firing. There was no factory at which to buy ready prepared clay, and there were no shops to run to when the glaze supplied failed. It was a self-made affair from beginning to end. The first thing that had to be seen to was the making of a kiln. It was found that amongst the patients were bricklayers, who were capable, under strict supervision, of laying the bricks. This was done from a simple plan of a small brick kiln, of the kind generally used as an experimental one for brick factories. It had been proved quite successful in Cornwall, where I had worked with my friend Gladys Reynell.

After the kiln was built, the next thing was to get the clay. This meant that all the patients who could walk would carry pieces of sacking or bags and shovels. As the hospital was in Devon, the finding of clay was no bother. (By the way, there is plenty of rough clay in our Australian ranges not suitable for commercial pottery perhaps, but quite useful for amateur work). At the end of the walk, the men would hump the clay on their backs, and then go back to the shed. Sometimes when the men were not able to carry the clay, a cart and horse would be begged from the farmer nearby, but generally we humped it back ourselves. When the clay arrived at the shed it was thrown into an old wooden tub and covered with water. The next day it was stirred by hands that needed such gentle treatment as the pressing together of some such substance as liquid mud. Memory goes back to one poor “Tommy” who had decided that his hands could not move. When they were gently “pushed” into this mud, he quickly decided to pull them out and use them on the “pusher,” who was myself. The doctor rushed to the rescue and took away a soldier who had been partly cured of a difficult complex.

After the men had mixed the mud and water to the consistency of a very thick cream, they scrubbed it through three different meshes (sieves). This left all the stones and rubbish in the sieves to be thrown away. The clean clay was then put into bags and hung in the sun to allow the water to drip out. After some days it was brought into the pottery shed and put on a table, where it was beaten and thrashed to get all the air out, and to set the clay in a fine smooth mass for work. Then the wheel had to be made, and the wheel was as primitive as the rest of the materials. It consisted of an iron shaft with a circular flat piece of iron attached to the top. This shaft had another length of iron joined to it half-way. The iron had a handle at its free end, which turned the shaft round and so revolved the circular plate at the top. The whole was enclosed in a box, which had a shelf and ledges that held the clay ready for throwing. One soldier would turn the handle, while another threw on the wheel. It would hardly seem possible that turning a wheel would start a cure in a case of badly shaking nerves, but this happened.

Many doctors visited the pottery shed either to see their patients, or to study how the scheme worked. There were also different visitors. Amongst these was John Galsworthy, who edited a kind of shell-shock paper. When Galsworthy’s visit was expected, the most shaking patient was put on to turn the wheel. This man had been for two years a martyr to the most convulsive shaking. It was discovered that he had one decided trait —an extreme personal vanity. When Galsworthy arrived with secretary and photographer complete, this patient was asked to try and keep still, and to look at a new pair of silk laces that had been put in his shoes. He did so, exercising a tremendous will so that the photograph should not be a failure. His doctor counted the seconds that became minutes, and another patient was taken away, well on the road to a cure that later became permanent. This man’s work is now in the War Museum in London.

Many men did not like throwing on the wheel. They were shown how to make objects by winding sausages of clay together. Some of these men produced fantastic animals and grim creatures that would have turned Dali green with envy. The doctors found these efforts interesting, and would try to get the men to part with them, but none of them would do so. They are to be found in unexpected places, such as miners’ homes and policemen’s barracks, where they remind their owners of the pottery shed at Seale Hayne Hospital on the Devon moors.

The kiln was used once a week. The firing was of wood or coal, and the glaze used for the pottery was of borax. It did not take long to cook the pots. Twelve hours, or perhaps a little longer, were enough, as the clay was of a low-firing grade. The morning the bricked-up door of the kiln was opened saw a scene like a village fair. Doctors with their patients of the pottery shed, and others not associated with the shed, would turn up in full force to see the results. The bidding of the soldiers to try and get possession of the precious objects was amusing. The doctors would offer large sums to try and get some, but they could hardly ever, if at all, part the pots from their makers. The kiln was later pulled down. Alas, it seems as if it may have to be rebuilt for other “Tommies.”

Other crafts interested the men. One was simple dyeing. This meant long walks on the moors, looking for plants that would give dyes. Sorrel was found to give a yellow, and the bulbs of the white iris a good black. These were brought back to the shed, cooked in jam tins, and later fixed with a mordant of common salt, alum, or some simple chemical. Thus the dye would not come out of the cloth when it was washed.

Dyeing was used in conjunction with batik work. A piece of unbleached calico would have a simple design drawn on it. This was retraced with hot wax, which was contained in tins that had lips to them. These were kept liquid over methylated spirit stoves. When the design had been waxed, the cloth was put into the boiling dye for a few minutes; then taken out and washed with soap and water. Any wax left on was scraped off with a knife. Cushion covers were generally the greatest extent of our ambitions. Wood-cutting was another craft that helped things along. There being no money for anything, everything that could be made to do was used. Cigar-box lids, old pieces of furniture that could be cut into shapes; any wood that had a fine grain – all was gratefully accepted.

The paint would be rubbed on an old tray with a photographer’s squeegee, and then over the upstanding design of the wood. A piece of dampened paper would be put on this, and rolled over with a clean roller. The paper was taken off, and the results shown around for criticism. Monotypes were also popular, as they caused no excessive expenditure of energy. This craft was done with a small piece of plate glass, zinc or copper, a soft hair brush, a roller, a rag, and some blotting paper. The worker began by rubbing a little oil and paint on to the glass. This he tried to get fairly even. Then he drew his design on to this, wiping out the white parts to be, and the highlights with the rag. Then he quickly placed a piece of paper on this drawing, rolled it over with his roller, and pulled it off the face of the glass. Many made Christmas Cards this way. The cards were of course unique, as it is only possible to get one copy by this method.

Then there were other crafts to interest the men. Stencilling was one. All the crafts are better than that horrible work known as crewel [embroidery] work. The most pathetic thing was to see a big wounded soldier plugging away in crewels at the motto, “God Bless our Happy Home,” which was often to be seen in the war hospitals.

This is an article on “crafts that help.” It is the moment to prepare for such work. As this is a personal article, it is not out of place to give advice on such matters. The Arts and Crafts Society are the people to be consulted. In New South Wales, Miss Florence Sulman, the president of this society, is always willing to help. She is extremely competent to do so.