A studio portrait of two diggers with empty grog bottles

Boy mascot company commander

Like other lads his age, Bill Taylor didn’t want to miss out on being a part of the greatest adventure of their lives. His parents’ plans for him to study medicine were dashed. However, life at the Liverpool camp was harsh and frustrating. Not just Bill but all the volunteers trapped at the dusty training grounds.

Liverpool camp, October 1916. (Image: AWM C01206)

‘Bill’ Taylor was stationed at the AIF training camps at Liverpool. He’d been there for over a month in February 1916.

Bill recalled1

Since I had been a commissioned officer in the School Cadets and knew as much of elementary military training as one could know without having seen a shot fired in anger… I was first given command of a platoon and, soon afterwards, of a company of Australian Imperial Force trainees.

Somehow it worked. The men in the company were from all walks of life. Labourers, solicitors, station hands, shearers, office clerks, tradesmen of all kinds, professional men, they all had volunteered for the AIF and been sent to the Liverpool camp to be turned into soldiers. There were some toughs among them, of course, but I never had the slightest trouble with them. Perhaps they regarded me as some sort of boy mascot company commander, but anyway they gave me an absolutely fair deal.

There were of course the usual impassioned appeals for leave, often on the grounds of family emergencies. Sick wives, children all with measles, the roof leaking, all the routine domestic disasters. Some were genuine, some obviously invented. I went along with them as far as I could, as long as it didn’t interfere with training and wasn’t too blatantly malingering. But when they were on parade they worked hard, their discipline something they themselves took pride.

However, the heat of the sun and humidity on this particular February morning would do nothing to cool hot heads.

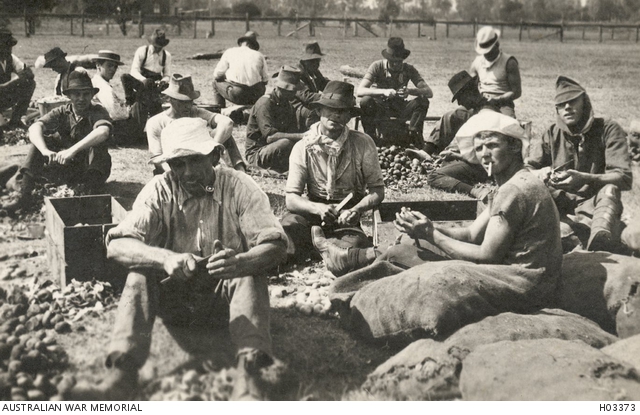

Liverpool, c. 1914. Army recruits peeling potatoes for the cookhouses. (Image: AWM H03373)

[T]here was a riot in the camp, stemming from some stupid injustice caused by a senior officer. The men made persistent orderly representations for this to be put right and were continually turned down. So they wrecked the camp, commandeered a train at Liverpool station, and drove it to Sydney where some thousands of them poured into the city with dramatic effect.2

Will we drill fourty hours? No!

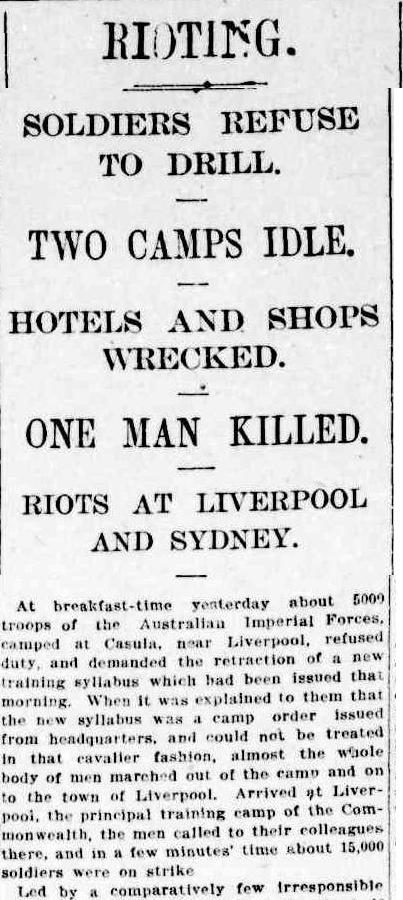

Trouble had been stirring in the dry, dusty, overcrowded Liverpool military training camps. Complaints about harsh treatment, including difficulty getting leave, had gone unheeded. The authorities, despite Royal Commission findings, failed to do anything about poor conditions inside the camp.

An increased training regime (from 36 to 40.5 hours a week)3 was all it took. The pressurised keg of collective frustration fermented and exploded.

Repeated requests for a wet canteen (serving alcohol) had also been ignored. Now the thirsty hot-heads were galvanised into action. On the morning of the 14th, they marched to Liverpool station, where things quickly got out of hand.

The Commercial Hotel, opposite the station, was ransacked first. Soldiers availed themselves of ‘every available bottle of liquor in the bars, broke open the cellar, and hauled 11 hogsheads of beer, rum, wine, whisky, etc.’ [4] onto the street. They then tapped and drank them dry.

According to newspaper reports, thousands of angry, rum-fueled AIF trainees in various states of intoxication commandeered the trains to Sydney.

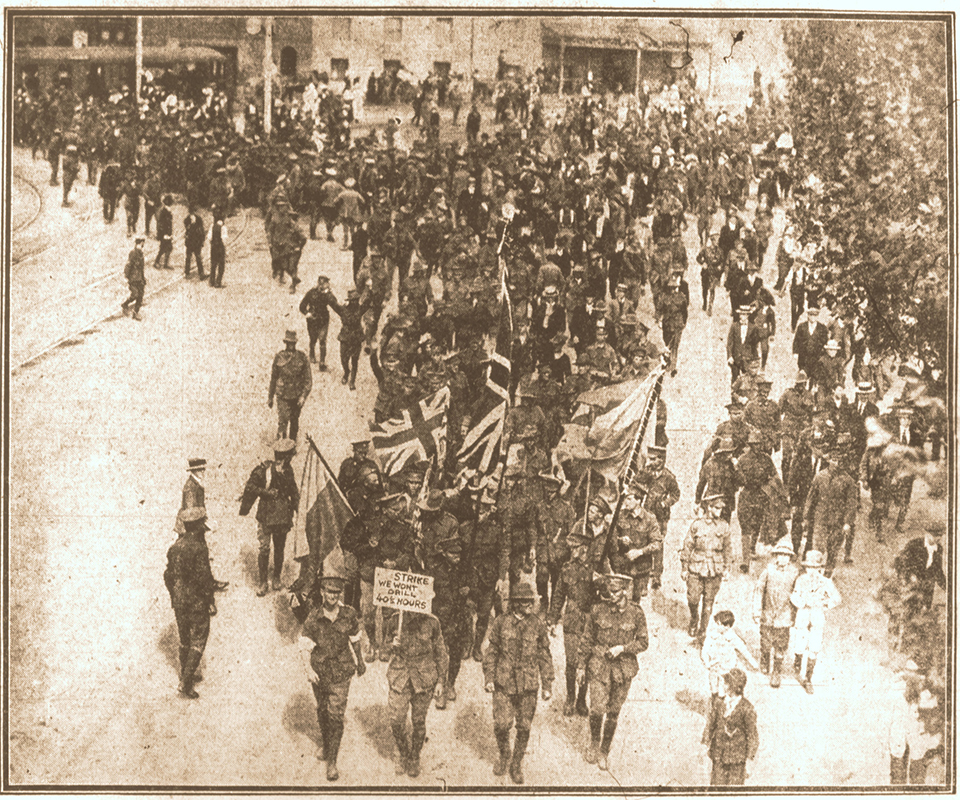

The volunteers noisily spilled out at Central Station. They ‘made a really fine spectacle’ marching through Haymarket, up Elizabeth and George Streets in columns, under the Union Jack, red flags and regimental colours, as if on parade. Chants and placards proclaimed Strike – We won’t drill 40 ½ hours! They let ‘all and sundry know what they thought of the camp and its new regulations’ to ‘the discordant sound of trumpets.’5

‘THE LIVERPOOL CAMP MUTINY. WAS IT “GERMAN INFLUENCE AND GOLD?” THE PROCESSION IN GEORGE STREET.’, The Mirror of Australia, 19 February 1916 (Image: Trove)

By the time the columns had reached Circular Quay, many had peeled off to wet dry throats at hotels. The remaining marchers were turned back at the turnstiles at the Manly ferry wharf. They then headed up Macquarie St., passing the Conservatorium. Here they stopped for a smoko resting at the Domain Garden Gates.

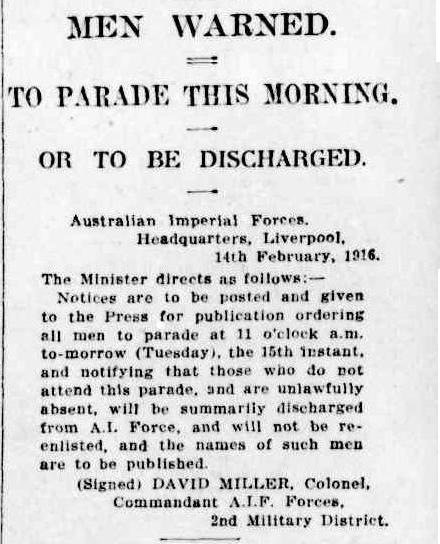

Unionism in Excelsis – Soldiers on Strike, Liverpool 14 Feburary 1916. Daily Telegraph, 15 February 1916, p 7. (Image: NLA NX 277)

Once rested — it was going to be at least an 8 hour day, after all — they invaded a nearby pub. But were soon ejected by the constabulary (once support had arrived from the police HQ across the road.)

The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 February 1916 (Image: Trove)

Other strikers proceeded to the Evening News demanding the newspaper change their advertising poster from ‘Riot At Liverpool’ to ‘Strike at Liverpool’, and issue an apology6 Their windows were smashed.

The “strike” descended into a maelstrom of civil disorder throughout the day.

Groups joined up with new arrivals, making their way through inner-city neighbourhoods, up side alleys and along major thoroughfares such as Cleveland and Shepherd streets in Chippendale, and Glebe Point Road, off Broadway.

Italians, Greeks, Chinese and locals who owned grocery stalls, seafood and “oyster bars” closed shutters and removed wares from shop-front windows.

The German Club in Phillip St. was set upon and had windows broken. German-owned or named businesses were also targeted. One individual was collared in Hunter St. in front of broken storefront window. The alleged looter was in possession of a box of imported cigars from ‘Kleisdorff’s’ tobacconist’s.

Taxi cabs ‘made off at a fast pace’ as soon as they saw anyone in khaki approaching. Troops were commandeering all forms of transport. Not just trains and trams

…motor cars, motor bicycles, lorries, drays, on all of these the men deposited themselves without as much as ‘with your leave.’ However, in the majority of cases, it was tolerated.7

Skirmishes occurred throughout the day with an overwhelmed police force. A struggle to arrest and free soldiers ensued, including an attempted mass break-out of soldiers from Regent St. Police lock-up by comrades armed with metal pipes.

Toohey’s Brewery in Chippendale became an obvious target as did the market stalls at the Queen Victoria Building and other parts of the city during the day.8

All the fruit was taken—and the soldiers spared nothing of the vehicle to get it. The men started to pelt the big crowd that was watching the proceedings from the balcony of the station and one of the tramway bridges. Oranges, peaches, bananas, all flew about, but misses were more frequent than hits.9

The Bulletin concluded:

If all the beer in Sydney had been buried in stone vaults at the moment that the human tornado struck the city, it would have stood a big chance of being torn from its place of seclusion.10

As the day wore on thousands of curious onlookers and by-standers joined in…11

“…there was a wild scene on the Druitt-street side of the Town Hall. A crowd had collected, and the police drove through it. Women fainted and men cheered or boo-hooed. Just at this moment, three distinct revolver shots were heard in Bathurst street, and the crowd surged around towards that thoroughfare, the few police being helpless to stem the tide. Luckily the mounted police arrived and dispersed the crowd, some of whom made towards Elizabeth-street, while others went down George-street. Many women took refuge in the grounds of St. Andrew’s Cathedral, and from behind the railings watched the mob rush past. Overall the recruiting message from the Town Hall blazed out “The Empire Calls,” but the young military men took no notice of the message, and continued their mad career.12

The cancellation of Liverpool train services, closure of public bars and shops, baton charges by police, and the deployment of 1,500 militia eventually funnelled soldiers back to Central.

Small bullet-hole in the marble by the entrance to platform one at Central Station. (Image: Chris McKeen / The Daily Telegraph)

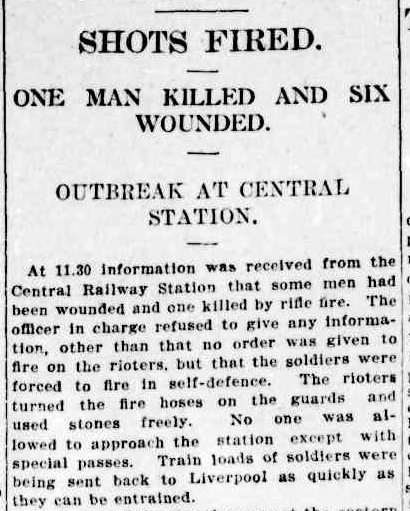

By about 9pm a large, surging group of AIF recruits chanting Will we drill forty hours? No! faced off against armed militia forming picket lines near Platform 1.

In the confusion shots rang out.

The scene of the shooting was at the eastern end of the assembly platform, between the entrance portico and near the lost property depot. It appears that a number of soldiers […] gathered at the lavatories at this end of the station and the iron gates were drawn against them. Some of those thus imprisoned brought a large hose into use and directed it against the military picket.13

The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 February 1916 (Image: Trove)

Shouts of “blacklegs” and “scabs” were answered with rifle butts in a violent encounter.

Reports vary but it seems a trapped soldier fired shots from a revolver into the ceiling and this was answered by a volley from the military picket and ‘a number of men fell. Seven of these were found to be more or less injured by rifle fire…’14

Of the 50 or so cartridges discharged one bullet found its mark, shooting a 6th Light Horseman ‘clean through the left eye.’

The mortally wounded man Trooper Ernest William Keefe was moved to the “Refreshment room” and his recently deceased body taken to the Mortuary Station for later examination, service and burial at Waverley Cemetery. He left behind a fiancé as well as a grieving mother.

His ‘cause of death’ was described, in sobering detail, at the coroner’s inquest.

There were abrasions on the chin and the bridge of the nose, and an entrance wound of a bullet on the right cheek, above the angle of the mouth. The lower jaw was fractured in front, and the tongue was much lacerated; the left, internal jugular vein was torn. The bullet passed out the lower part of the left side of the neck and then entered the left shoulder fracturing the collar-bone and shoulder-blade, and was found on the outer side of the shoulder more or less broken up and flattened out.

Based on the evidence given by Lieutenant Colonel Logan and Constable Bailey —

The Coroner announced that Keefe died from the effects of a bullet wound in the head justifiably inflicted upon him by a military picket in lawful execution of their duty in maintaining public peace and suppressing a riot of mutinous soldiers and civilians.15

Taylor steers clear of turbulence

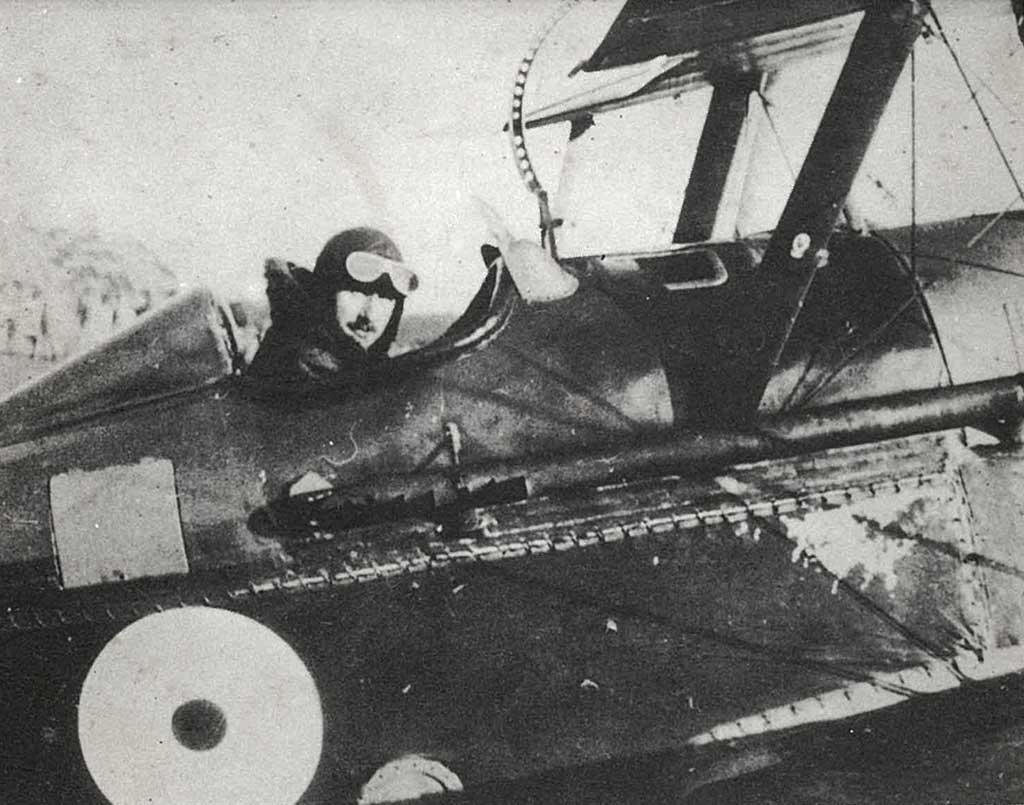

“Bill” Taylor in 1917 when serving with the Royal Flying Corps. (Image: Sopwith Scout 7309, Cassell)

Knowing that strike action and revolt would be on the cards on the morning of the 14th of February, 2nd Lieutenant Taylor had to find a way. Between the heavy-handedness of camp authorities, and duty of care he felt towards the men in his platoon.

I had advance information this was going to happen. Our battalion was not closely involved. But it wasn’t difficult to see that there would be trouble for all the men caught taking part in it. I didn’t want my chaps swept up into this shambles. So I lined them up on the parade on the morning of the final ultimatum to the camp commandant and told them what I thought was going to happen. I then told them we were going to march out immediately into the country on a skirmishing exercise, and that any man who wanted to stay and join the mutiny must fall out now and leave the company. There were a few sideways glances, but not a man moved.

I kept them on the march, well out along the Holsworthy road, and into the bush for a smoko. Then we began the exercises for the day. By the time we got back to camp the worst of the trouble was over.16

In this way Taylor’s platoon was able to avoid, in his words, the day’s “shambles,” sore heads and prosecutions that followed the men that had participated.

The Sydney Morning Herald, 15 February 1916 (Image: Trove)

The strike’s aftermath

Reports vary but upwards of 1,000 men did not show up for parade and roll-call the next day and were immediately discharged17.

Up to 30018 were charged, many for “mutiny.” Of those charged, 36 were convicted in state courts. ‘Ringleaders’ (some just 16 years old) were sentenced to up to 5 years of hard labour. One 16 y.o. soldier caught up in the furore faced 6 months of hard labour. His crime “maliciously injuring a plate glass window” (at the Grace Brothers flagship store on Broadway.)

The Liverpool “riots” (as coined by newspapers at the time, or “strikes” as the participants insisted on) can be viewed as one event, building to the General Strike of 1917 and plebiscites against Conscription

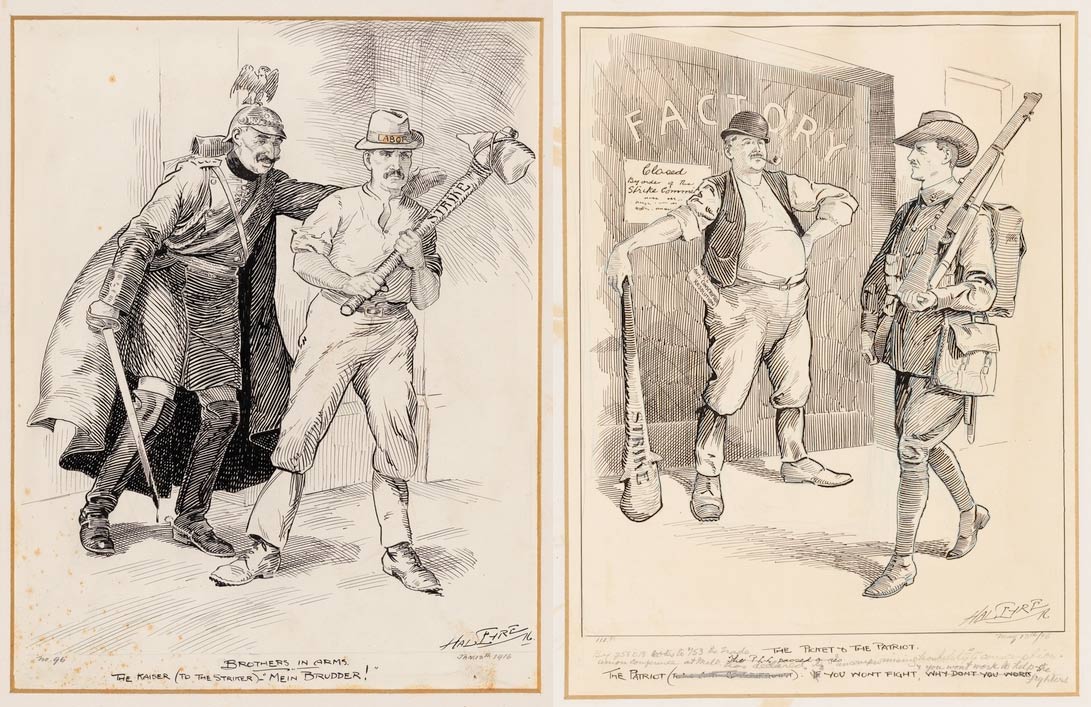

Anti-labour propaganda in the Daily Telegraph. Left: Brothers in arms – the Kaiser (to the Striker): “Mein brudder!” 13 Jan 1916. Right: The picket to the patriot: you won’t fight, why don’t you work. 13 May 1916. Cartoons by Hal Eyre. (Images: SLNSW)

Feb. 14th., 1916 doesn’t sit comfortably with the ANZAC mythology and has been largely forgotten. A small bullet hole at Central Station the only remaining physical evidence that a struggle took place.

Max Dupain’s photograph of A Barmaid at Work in Wartime Sydney. Petty’s Hotel, Sydney, 6pm, 1941.

The “six-o’clock swill” became part of the Australian vernacular and way of life from 1916 until the mid 50’s, and was an unintended outcome of the day’s drinking “binge”.

Although the battle began as a dispute over working conditions it gave the temperance movement, which had been gathering support for many years, a compelling argument to convince the people of New South Wales to vote in June 1916 for the six o’clock closing of all pubs. The Bulletin denounced the link as ‘hysterical…pub hours were no more to blame than the railway timetable or the width of the Redfern tunnel.’21

In the aftermath, the military camps at Casula and Liverpool were broken up and their occupants moved elsewhere, leaving only the German concentration camp and its unfortunate internees (POWs and ‘enemy aliens’) to occupy the area for the duration of the war.

December 1916. Men of the 5th Division resting by the side of the Montauban road, near Mametz, while enroute to the trenches. (Image: AWM E00019)

Most A.I.F. recruits who participated in the strike on Feb 14 were shipped overseas. They served their country in the mud and trenches of the Western Front or the deserts of the Middle East. Many made the ultimate sacrifice, others returned home with physical injury and psychological trauma.

Taylor flies free

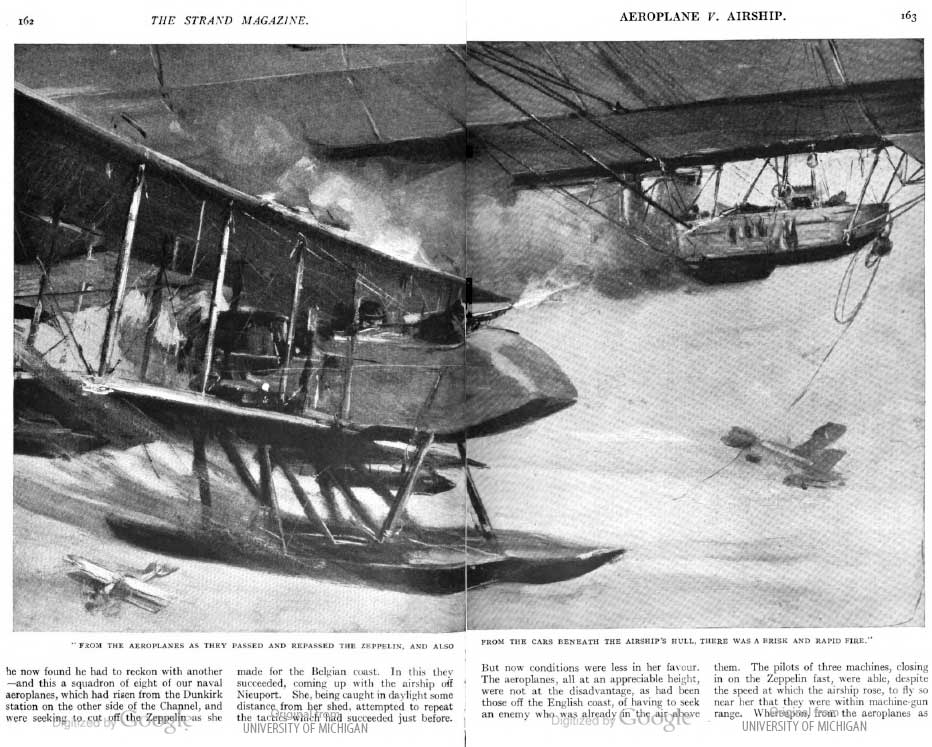

Despite his efforts and months of good service, P.G. Taylor could not convince the camp authorities to release him for service abroad.. After reading an illustrated article about British aeroplanes destroying the German airship hangars at Cuxhaven in The Strand. At that moment, returning back to camp from leave, he was inspired to pursue his newly found life’s purpose — to fly.

Aeroplane V. Airship. The Strand Magazine, 1916.

Aeroplane V. Airship. The Strand Magazine, 1916.

He describes his dread at returning to camp.

The train was approaching Liverpool. The thought of the dust and the parades was horrible, something to be left for the brilliance of these diving aircraft… getting to grips with the enemy without all the sordid complications of war on the ground.

The next day I made a direct request for transfer to the Australian flying Corps. My request was ridiculed. I was told there was a war on. I was in the army.

However, for “Bill” Taylor —

The idea of flying grew quickly into an obsession, so that every wasted minute in the camp became almost unendurable… discreet inquiries brought the advice that I should apply for leave, so that I could go to England at my own expense. There I would be able to join one of the flying services. But first I must escape the clutches of the Army.

I knew that any further conventional approach to the authorities would be useless. I had already been turned down and I couldn’t put forward any new circumstances to make them change their minds. But by then I didn’t care how I got out of the army. I decided to use any family influence I might have to get free of that dusty camp.19

Bill Taylor’s father Patrick Thompson Taylor. Mayor P.T. Taylor was horrified by the idea of flying (in a war – that was suicide!) But his son’s enthusiastic arguments eventually persuaded him. Once convinced, P.T. Taylor was able to use his considerable political influence,

…he did everything in his power to get me away as soon as possible. He was in a position to have my request dealt with on a higher level. Neither he nor I had any misgivings about resorting to this action—I wasn’t trying to avoid the war. I was trying to reach it

In a few days, I was told to report to the camp Commandant’s office. I arrived punctually and saluted, eagerly waiting instructions. The scene was brief; I had been granted leave in the terms of my request. I was free to go.20

Bill had ‘escaped the clutches of the Army’ and taken his first steps: to emulating the ‘brilliance’ of those pilots he’d imagined becoming.

‘Sir Gordon Taylor. A photograph taken in 1917 after he had flown more than 100 offensive patrols and escorts over the lines in France in the Sopwith Scouts of 66 Squadron. Here, a Fighting Instructor, he is seen in the cockpit of an SE5.’ (Image: Sopwith Scout 7309, Cassell)

Whilst stationed with 66 Squadron in France, Bill bumped into a ‘blast from the past.’

D’you remember that day, Cap?

Whilst on short leave to Amiens, Taylor and his fellow officers would buy soft furnishings, lamps, and picture postcards ( Kirchner girls and ‘select illustrations’ from La Vie Parisienne) to make their bare Nissen huts more homely.

‘Part of the “..life of extreme ease” Sleeping quarters above and living quarters, Estree Blanche.’ Photograph and caption by P.G. Taylor.

‘Part of the “..life of extreme ease” Sleeping quarters above and living quarters, Estree Blanche.’ Photograph and caption by P.G. Taylor.

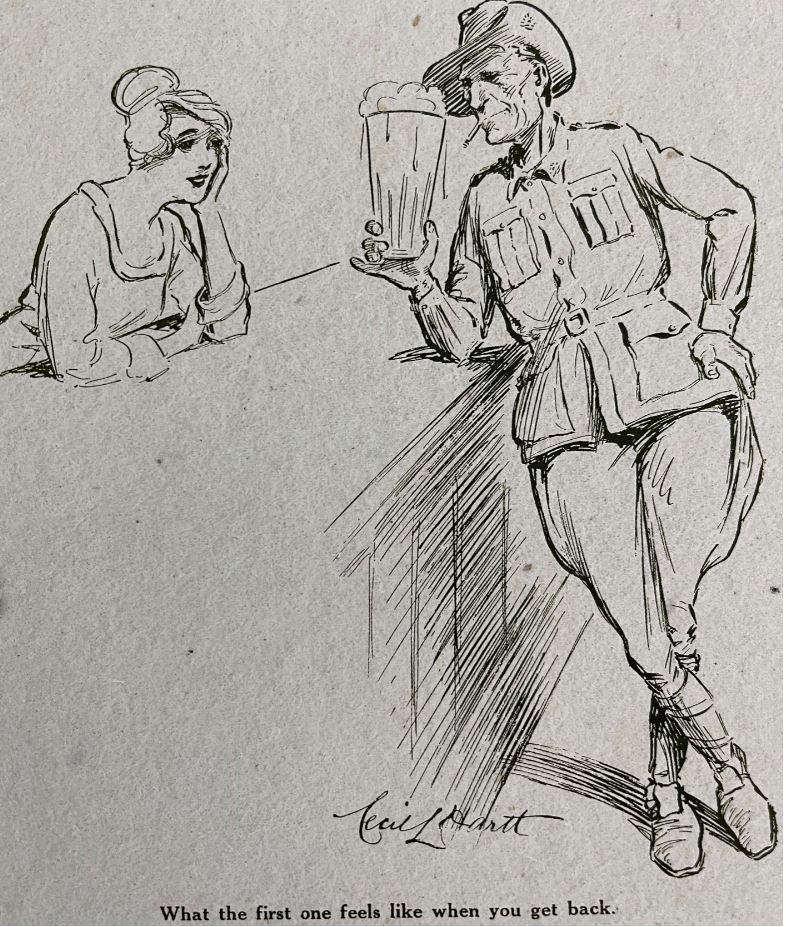

On their outings the pilots frequented cafes and other establishments. One regular drinking hole was ‘Charlie’s Bar’:

Looking back I realise that this surely must have been one of the toughest places of its kind on earth. Charlie’s Bar was the retreat of all sorts of characters from the active services, including usually a few flying corps pilots from nearby aerodromes. It was a dangerous place in which to become involved in an argument because most of its patrons had come from scenes of violent death, so that the reactions of some to the most trivial disagreement, particularly if they were well on the grog, were liable to be extremely violent. It was in these circumstances that by pure chance I met again one of the old soldiers who had been in my training company at Liverpool camp in Australia, and, as it happened our mutual recognition, of each other could hardly have happened at a better moment.

On this occasion, Taylor and three of his flying mates had decided to drop in to Charlie’s Bar for a drink before returning to Vert Galand Farm where the squadron was stationed.

There was the usual crowd of men from the war; some pretty full and argumentative, including two Australian soldiers who were quite near us at the bar.

I hadn’t been there long before some of the more audible remarks about the Flying Corps began to come our way.

“Where’s you blokes when the Jerries come shootin’ us up in the trenches? Where’s th’ flamin’ Flyern Corps then?”

It was getting bad, and very soon something would have to be done. Then one of the Australians turned towards me, and suddenly stopped in his tracks, his face lighting up with recognition.

“Well, stone th’ flamin’ crows! Its Cap! Good ole Cap-sir”

I recognized him immediately, one of the toughest characters I ever had in the company at Liverpool, often at trouble at home, but fundamentally a good man. To get him clear of some awkward disciplinary situation I had recommended him for the next group of men to go overseas. ‘Cap’ was a sort of honorary title given me by the men when I was a company commander, which normally carried the rank of Captain, though I was in fact a temporary second lieutenant.

Taylor says he felt pretty relieved by the mutual recognition, as it had diffused a potentially explosive situation. The A.I.F. boys were obviously spoiling for a fight…

‘Murphy!’ I greeted him. ‘Well, you finally made it. When did you get away?’

“Came with that reinforcement mob, Cap.” And, turning to his pal he quickly cleared up any threatening atmosphere,

“Ar-r Jacko; the Cap’s all right. Too bloody right e’ is. Marched us outer the flamin’ camp when th’ riot was on, and saved us from the clink. D’you remember that day, Cap?”

‘Yes I certainly do. Been up the line yet, have you?’

“To right I have been, Cap. Always there when the numbers go up- the ole Murph.”

We got onto the subject of the Huns sweeping down and strafing the trenches and I told him about it from our end. It did some good, I think. I was sorry to leave old Murphy, and I have often wondered what happened to him: whether he survived the war.

As we left he exhorted us to great deeds and ferocious action, ending “Good luck to yer, Cap-sir! Get th’ bloody Baron!”

I raised a hand to him and we left. Von Richtofen in his Albatros! That was unlikely.

‘Flying Circus’ lined uo. Richthofen’s is the all red Albatros.

‘Flying Circus’ lined uo. Richthofen’s is the all red Albatros.

Sir Patrick Gordon Taylor was not destined to tangle with the Red Baron but he did on at least one occasion try to engage enemy aircraft attacking front line trenches. Bill Taylor deplored the killing and all the other evils of war.22 after his first confirmed kill. But he survived to become famous as a co-pilot and navigator with Charles Kingsford-Smith and Charles Ulm.

We are grateful that later in life he recorded his experiences, including his experiences as a boy mascot company commander, on a Valentine’s Day like nothing before, or since, in the nation’s history.

Further reading

- Newspaper articles tagged 1916 AIF Mutiny – Casula Training Camp in Trove

- The other charge of the Light Brigade — Carl Reinecke, Griffith Review

- Wise, Nathan 2011-11-01, ‘‘In military parlance I suppose we were mutineers’: industrial relations in the Australian imperial force during World War I.’ Labour History: A Journal of Labour and Social History, no. 101, pp. 161(16).

Follow the P.G. Taylor story in the following articles:

Raglan St to RFC: Mayor P.T. Taylor

Raglan St. to RFC: Bill Taylor’s school days & calling to the skies.

Raglan St. to RFC: Pilgrimage to ‘the silent fields’

Raglan St. to RFC: Bill Taylor: boy mascot company commander avoids the Valentine’s Day mutiny

Fledgling wings: Lt. Taylor inspires Gunner Allport.

Bloody April, 1917: P.G. Taylor survives

Lt. P.G. Taylor & ‘The doomed Rumpler’

Capt. P.G. Taylor, MC; Memories & Memorabilia

Footnotes

1 Taylor, P. G. (Patrick Gordon), Sir 1968, Sopwith Scout 7309, Cassell, London, 1968

2 Ibid.

3 1916 ‘RIOTING.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 15 February, p. 9, viewed 13 February, 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15646740

4 1916 ‘AT LIVERPOOL.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 15 February, p. 9, viewed 13 February, 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15646739

5 1916 ‘CITY PARADE.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 15 February, p. 9, viewed 13 February, 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15646737

6 Reinecke, Carl 2010, ‘The other charge of the light brigade’” Griffith Review, no. 28, pp. 226-231.

7 1916 ‘CITY PARADE.’, The Sydney Morning Herald

8 Reinecke, Carl 2010, ‘The other charge of the light brigade’

9 1916 ‘CITY PARADE.’, The Sydney Morning Herald

10 Reinecke, Carl 2010, ‘The other charge of the light brigade’

11 Ibid.

12 1916 ‘AT THE TOWN HALL.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 15 February, p. 9, viewed 13 February, 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15646865

13 1916 ‘MILITARY RIOT.’, Singleton Argus (NSW : 1880 – 1954) , 17 February, p. 4, viewed 13 February, 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article80177971

14 1916 ‘SHOTS FIRED.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 15 February, p. 9, viewed 13 February, 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15646738

15 1916 ‘SOLDIERS’ RIOTS.’, Kalgoorlie Western Argus (WA : 1896 – 1916), 7 March, p. 24, viewed 13 February, 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article33602446

16 Taylor, Sopwith Scout 7309

17 Newspapers reported up to 15,000 men were involved but it was probably closer to 5,000 as many soldiers were stranded back at Liverpool once train services to the city were stopped.

18 Newspapers at the time said 330 were charged, a recent study (Reinecke) says 279.

19 Taylor, P. G., Sopwith Scout 7309

20 Ibid.

21 Reinecke, Carl 2010, ‘The other charge of the light brigade’

22 Isaacs, Keith 1990, ‘Taylor, Sir Patrick Gordon (1896–1966)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/taylor-sir-patrick-gordon-8763/text15357, accessed online 13 February 2016.