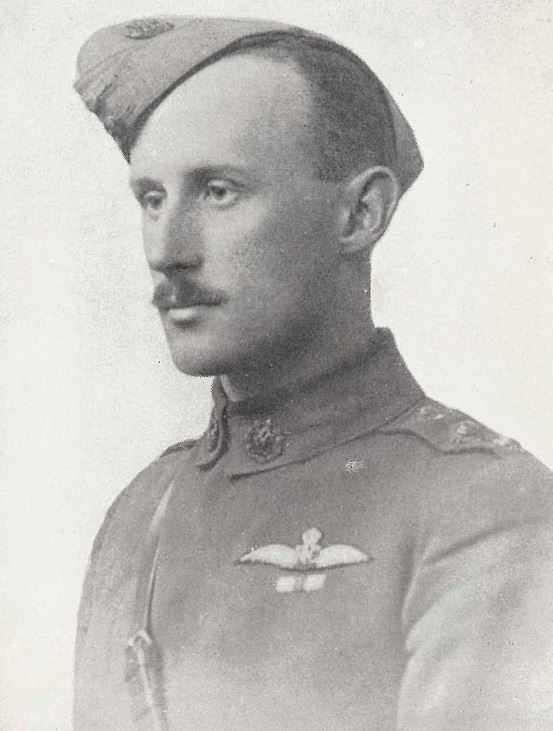

Left;The London Gazette Ay 11, 1917 www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30064/supplement/4592 The Gazette retrieved online 24/04/17. Right; Military Cross. Source: Wikimedia commons. Above photographic portrait, ‘Myself, in 1917’ from Sopwith Scout 7309.

Left;The London Gazette Ay 11, 1917 www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30064/supplement/4592 The Gazette retrieved online 24/04/17. Right; Military Cross. Source: Wikimedia commons. Above photographic portrait, ‘Myself, in 1917’ from Sopwith Scout 7309.

On the 24th of July 1917, 2/Lt. P.G. Taylor was awarded the Military Cross and promoted to Captain. Unfortunately, he received terrible news in the following days which overshadowed this prestigious honour. Today many of Bill Taylor’s belongings are kept at the Australian War Memorial.

Congratulations, Wallaby

Taylor recalled:

One evening Andrews [66 Squadron.‘s C.O.] came to my tent. ‘Congratulations, Wallaby.’

‘Congratulations? what for?’

‘MC. You’ve been awarded the Military Cross.’

I could hardly believe it. I hadn’t got many Huns. None of us had. But it would be absurd to pretend that I was indifferent to this recognition. I was delighted to be the recipient of one of the few awards which came the way of our squadron and greatly encouraged.

Later I saw the CO in the squadron office and he gave me a piece of the purple and white ribbon.

‘and, Taylor,’ he added, ‘see that you are properly dressed in the Mess tonight.’ Lambert, who had his own sources of information, was waiting with more formal congratulations – and a needle already threaded…1

Taylor was posted to Calais a few days later to intercept Gotha bombers en route to England.

In a letter to his mother he wrote of his new posting and the subsequent need for summer attire:

I have had a couple of swims in a creek 5 miles from here; it is fairly cool in the water but the sun is quite hot..I had a cool uniform made by a tailor in Sackville St. and it arrived a couple of days ago, and is not at all bad…2

Bill also mentioned that, by chance, he’d found out where elder brother Ken was stationed:

you will be glad to hear that I know where Ken is. One of our chaps had a forced landing near a town north of here and Ken saw him in a shop and asked him what squadron he was from. I hope to be able to fly up to where he is and see him but can’t be sure of that yet.3

Terrible news

Taylor recalled miraculously finding a lucky charm lost by a pilot nick-named ‘the ratter.’

That night we had a terrific celebration in Calais – a long affair of French food and bottles of champagne – going on late into the night. the Crossley tender brought us home, feeling no pain: a glorious ride. I tripped on the guy rope of my tent, recovered control and, putting on my clothes with a vague neatness on a chair, passed out on the bed. Fortunately there were no Gotha raids in the morning.4

The good times came to a halt:

We were down at the sea the next day, and in the evening before Mess the CO came to my tent. I rose, feeling rather awkward. Major Boyd was looking serious. There was a moment of silence. then he said, ‘I’m sorry to tell you, Taylor, that your brother has been killed.’ Brother? that would be Ken. I registered the words; but not, for a moment their meaning…5

Presumably, in shock, Bill asked how his brother had died. His CO provided the details, but to Bill:

The details seemed futile and superfluous. Ken was dead: killed in action. How didn’t really matter. The fact was complete in itself.6

Corresponding to his mother in England, he put on a brave face:

Dear Mother,

I just got the telegram about Ken, and I thought to write to you right away. I don’t think I can say anything as you know how I feel about it and can understand how you feel… Don’t worry..I am not going to get down about it; we have just got to face what nearly every other family has to do, and am absolutely certain that Ken would much rather we took it as cheerfully as possible, hard as it may seem. It is good to know that Don, although at home, is doing his part too.

He added what was originally to have been his good news:

I’ll try to get away on leave as soon as possible, and I was keeping a little surprise for you, but I will tell you now: it is not much, but I got the Military Cross about a week ago.7

Bill Taylor took two weeks leave and consoled his grieving mother, visiting England at the time.9 Bill flew to his brothers grave as soon as he was able. He visited the permanent cemetery and memorial again in 1960.

Mendinghem cemetery during the war. Image: René Matton

Exceptional dash and gallantry

Lt P.G. Taylor’s citation read:

Lt. Patrick Gordon Taylor, R.F.C.,

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He has taken part in over forty offensive patrols at low altitudes under heavy fire from the ground. He has always shown exceptional dash and gallantry in attacking large formations of hostile machines, setting a very fine example to all his comrades.8

A digital render of Sopwith Pup A7309 flown by Taylor in June 1917. Image: Panthercules, Rise of Flight forum

A digital render of Sopwith Pup A7309 flown by Taylor in June 1917. Image: Panthercules, Rise of Flight forum

Bill Taylor’s enthusiasm for solo attacks on German Jastas was short lived. Dash and gallantry looked good on paper but strategy and teamwork were key to survival. Sometimes discretion proved the better part of valour. Bill Taylor described one patrol:

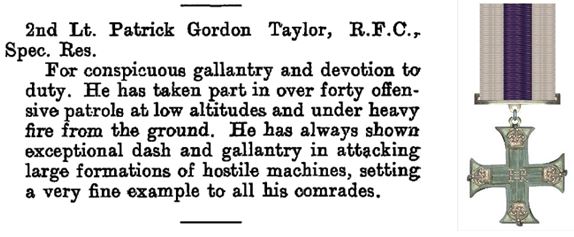

We encountered two Huns [German 2 seaters] flying south, east of Zonnebeke. Andrews and Sammy Luke took one and I took the other. My Hun didn’t see me until I was in the right position for attack, or he may not have seen me at all. After my short gun burst his nose went down and he dived vertically to the earth. We had attacked at about 6,000 and I last saw him going down vertically, so low that it seemed he should have hit the earth. At this moment we set upon a new formation of Hun fighters. They were silver coloured machines, slimmer than the Albatros and apparently very agile. They had us cold, and seemed to be even faster than the Albatros, and able to turn very quickly.

We wore these Huns down by never giving them a target; and eventually escaped back over the lines- an undignified performance, but one in which we had no other choice. It seems from later reports that these were Pfalz Scouts. They didn’t, however, supercede the Albatros D5 and D5a.9

Albatros DVa (Kurt Katzensteins pilot) Source: Wikicommons

Albatros DVa (Kurt Katzensteins pilot) Source: Wikicommons

The AWM’s artefacts

The Australian War Memorial’s collection of Sir P. G. Taylor’s memorabilia includes a ‘maternity style jacket’ and scarf.

Royal Flying Corps private purchase khaki woollen maternity-style jacket bearing the rank insignia of a captain. Label marked in black ink ‘P. G. Taylor Esq. Aug 7. 1916’. Source AWM

Royal Flying Corps private purchase khaki woollen maternity-style jacket bearing the rank insignia of a captain. Label marked in black ink ‘P. G. Taylor Esq. Aug 7. 1916’. Source AWM

Purple and white striped rayon scarf. The ends of the scarf is finished with a fringe of purple and white tassels. Associated with the service of Captain Patrick Gordon ‘PG’ Taylor. Source AWM

Purple and white striped rayon scarf. The ends of the scarf is finished with a fringe of purple and white tassels. Associated with the service of Captain Patrick Gordon ‘PG’ Taylor. Source AWM

Taylor explained:

The regulation uniform of the time was khaki. A rather smart forage cap, and a tunic done up to a high collar and folding across the chest to button up invisibly at the side. It was known in service as a ‘maternity jacket’, possibly because it made any superfluous weight around the middle extremely visible. The uniform was completed by riding breeches, and either putees or field boots. The latter of course gave tremendous scope, since nowhere could the field boot be so exclusive, so polished, so superb as in London.10

Pilots, on both sides, kept lucky charms and mascots:

[Bill Taylor] always carried a piece of Archie (anti-aircraft) shell which Ellins [his mechanic] had extracted from the wing of my machine in the pocket of my flying coat, and I also had a small black cat, given to me as a mascot by my mother, attached to my instrument panel. It had comical whiskers and it used to look at me with a kind of humourous disdain which made me feel a damned fool for being scared of Archie.11

The black cat, looking a little worse for wear is also held by the AWM:

Description: Black cotton velvet cat with glass eyes and a red silk ribbon tied in a bow around the neck. the cat is missing its ears and whiskers. The cat’s tail has been hand repaired. History / Summary: Associated with the service of Captain Patrick Gordon ‘PG’ Taylor. Taylor was given this cat by his mother as a mascot and flew with it attached to his aircraft’s instrument panel during the First World War.

Description: Black cotton velvet cat with glass eyes and a red silk ribbon tied in a bow around the neck. the cat is missing its ears and whiskers. The cat’s tail has been hand repaired. History / Summary: Associated with the service of Captain Patrick Gordon ‘PG’ Taylor. Taylor was given this cat by his mother as a mascot and flew with it attached to his aircraft’s instrument panel during the First World War.

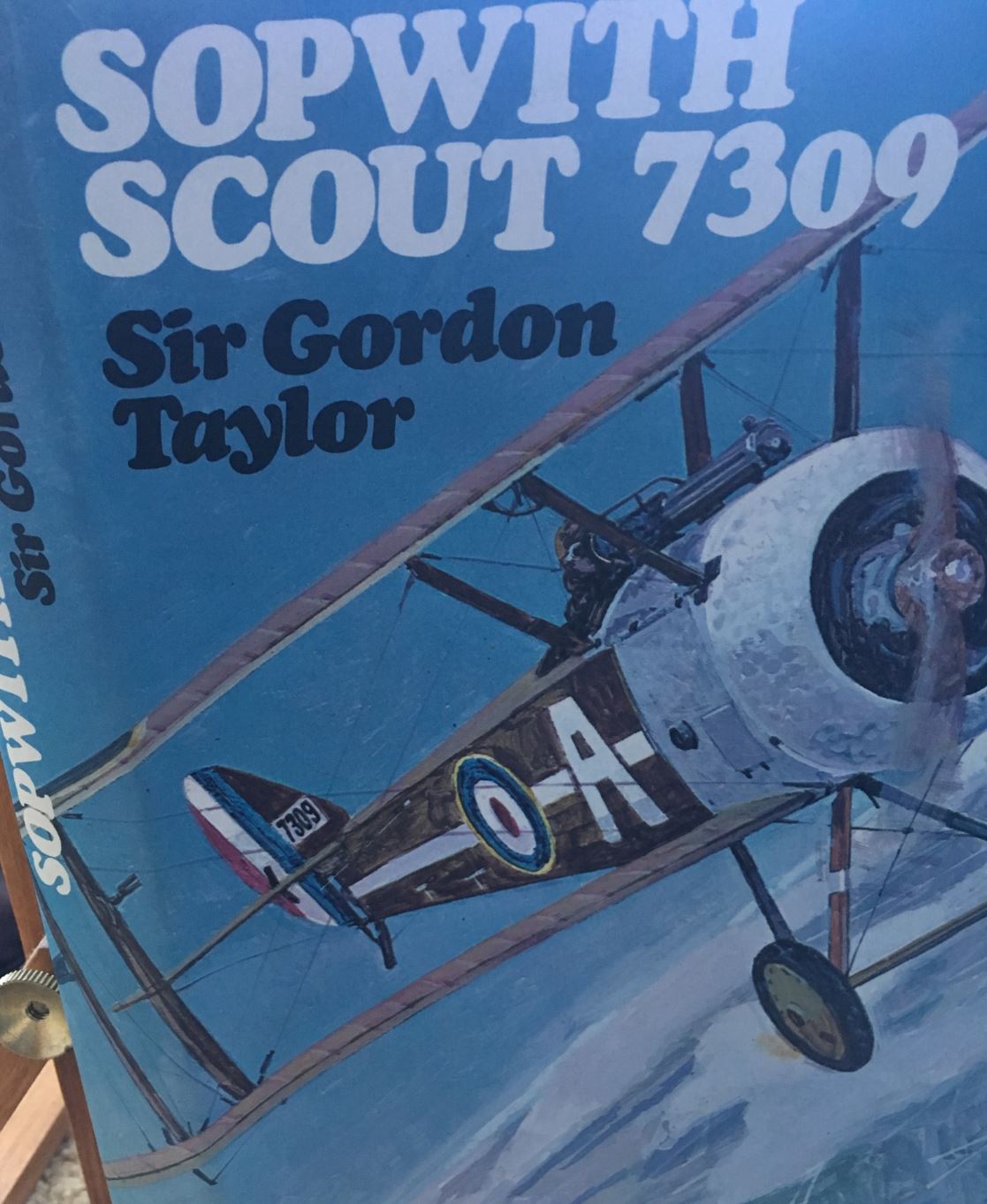

Distant events brought back to life

In the last years of his life Bill penned his memoirs. With only his logbook and 50 year old memories to draw on, he was surprised to find that in the writing they came back to me vividly, beyond my highest expectations.

To immerse myself completely in those distant events and to bring them to life again, I wrote in the very early mornings, before the life of the present day could impose itself on me; and there in those silent hours I found myself back at Vert Galand Farm aerodrome, with the sound of the guns at Arras rumbling in the night. I saw the chaps in the squadron, and in the high air over Carvin and Douai I stalked again the shark-like Albatros, flying my agile little fighter, Sopwith Scout 7309.12

‘Sopwith Scout 7309’ Published in 1968, two years after Sir P.G. Taylors death. Photo by the author.

‘Sopwith Scout 7309’ Published in 1968, two years after Sir P.G. Taylors death. Photo by the author.

He ended with the words:

Now that I have finished my story, it is with nostalgic regret that I let this splendid life slip away again into the past.

Though I deplored the killing and all the other evils of war, for me the actual hunt held in it some irresistible lure; the human qualities which it demanded for success were high, one good to live with amongst one’s companions.

…my incentive for writing this book, [has been] to try to explain what it is to be like to be a fighter pilot in the day of the Sopwith Scout and the Albatros; of Albert Ball, Georges Guynemer, and Werner Voss, and all the others.13

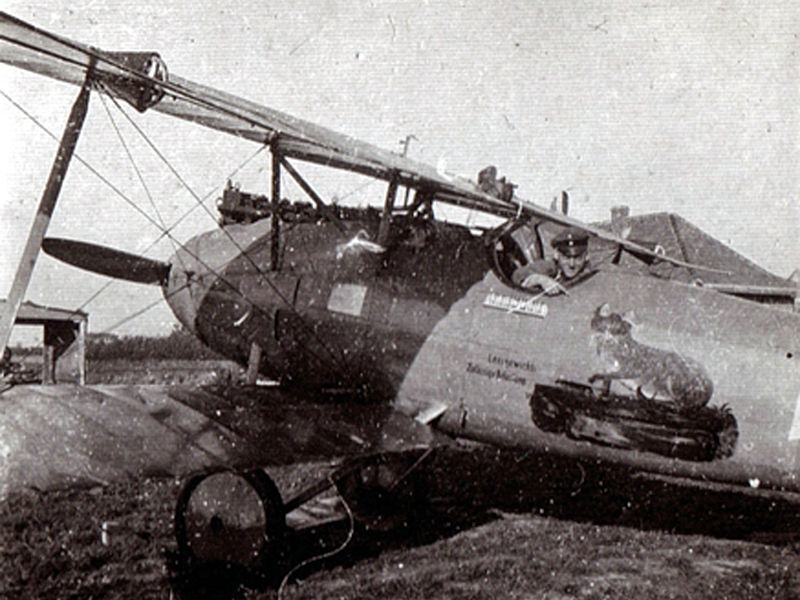

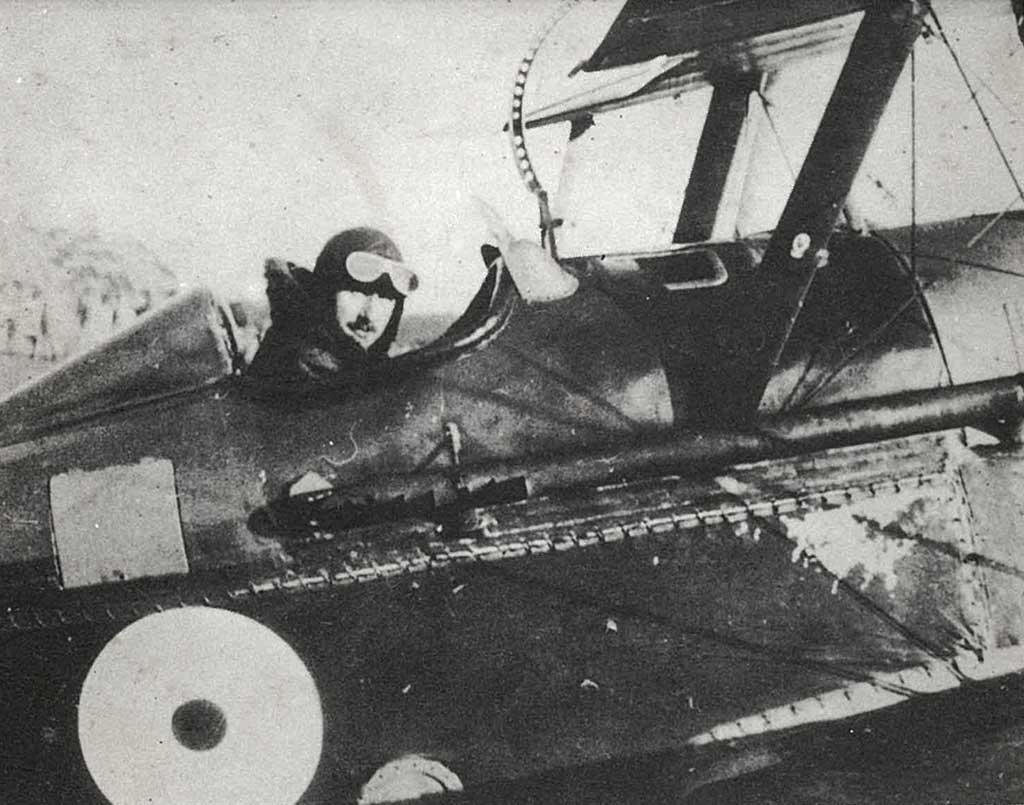

‘Sir Gordon Taylor. A photograph taken in 1917 after he had flown more than 100 offensive patrols and escorts over the lines in France in the Sopwith Scouts of 66 Squadron. Here, a Fighting Instructor, he is seen in the cockpit of an SE5.’ Image: P. G. Taylor, Sopwith Scout 7309, Cassell

‘Sir Gordon Taylor. A photograph taken in 1917 after he had flown more than 100 offensive patrols and escorts over the lines in France in the Sopwith Scouts of 66 Squadron. Here, a Fighting Instructor, he is seen in the cockpit of an SE5.’ Image: P. G. Taylor, Sopwith Scout 7309, Cassell

Taylor authored the following books on his flying experiences: Pacific Flight (1935), VH-UXX (1937), Call to the Winds (1939), Forgotten Island (1948), Frigate Bird (1953), The Sky Beyond (1963) and Bird of the Island (1964).

His papers and family correspondence are held by the National Library of Australia and the Powerhouse Museum, which also houses Frigate Bird II.

Bill’s military records are not held by Australia’s National Archives – both his (AIR 76/498/27 PDF, WO 339/68144) and Ken’s service details are held at the British National Archives in Kew, London.

Their names are not recorded on the Mosman memorial.

Follow the P.G. Taylor story in the following articles:

Raglan St to RFC: Mayor P.T. Taylor

Raglan St. to RFC: Bill Taylor’s school days & calling to the skies.

Raglan St. to RFC: Pilgrimage to ‘the silent fields’

Raglan St. to RFC: Bill Taylor: boy mascot company commander avoids the Valentine’s Day mutiny

Fledgling wings: Lt. Taylor inspires Gunner Allport.

Bloody April, 1917: P.G. Taylor survives

Lt. P.G. Taylor & ‘The doomed Rumpler’

Capt. P.G. Taylor, MC; Memories & Memorabilia

Footnotes

1 Taylor, P. G. (Patrick Gordon), Sopwith Scout 7309 London: Cassell, 1968 p.113

2 Ibid.

3 Taylor, P.G., unpublished notes in MS 2594, Papers of captain Taylor, NLA; in Searle, Rick The man who saved Smithy Allen & Unwin; Crows Nest, NSW 2015 p.

4 Taylor, Ibid p.113

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Taylor, P.G., unpublished notes in MS 2594, Papers of captain Taylor, NLA; in Searle, Rick The man who saved Smithy

8 The London Gazette Ay 11, 1917 www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30064/supplement/4592 The Gazette retrieved online 24/04/17

9 Taylor, P. G., Sopwith Scout 7309

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid., p.120-121

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.