Lt. Allport beside Re8. Reproduced with permission from the Australian Society of WW1 Aero Historians

Lt. Allport beside Re8. Reproduced with permission from the Australian Society of WW1 Aero Historians

Conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty.

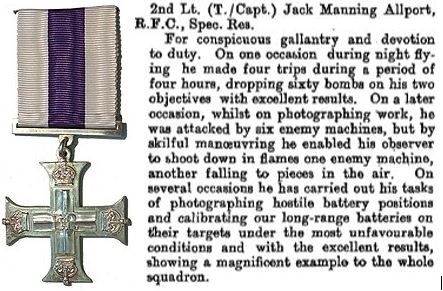

Military Cross and Allport’s citation in London ‘Gazette’.

Military Cross and Allport’s citation in London ‘Gazette’.

Allport’s citation for the Military Cross , published in the London Gazette, read:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. On one occasion during night flying he made four trips during a period of four hours, dropping sixty bombs on his two objectives with excellent results. On a later occasion, whilst on photographing work, he was attacked by six enemy machines, but by skilful manoeuvring he enabled his observer to shoot down in flames one enemy machine, another falling to pieces in the air. On several occasions, he has carried out his tasks of photographing hostile battery positions and calibrating our long-range batteries on their targets under the most unfavourable conditions and with the excellent results, showing a magnificent example to the whole squadron.

Excerpts from his interview in 1969 shed light on why he was awarded a Military Cross:

5 Squadron: RE8s

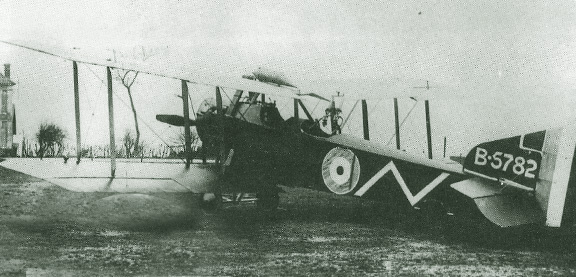

Re8 of 3 Squadron, AFC.

Re8 of 3 Squadron, AFC.

Allport describes the aircraft he did his final training in, the R.E.8:

…it turned out to be a winner, although the Mess Room chat centred on this new reconnaissance plane being an “incinerator” of pilots; it burnt up quite a few…Nearly all the R.E.8’s which crashed in England caught fire easily because the emergency tank was only an inch or so from the rear of the engine and burst if the engine was knocked back on to it.

When Allport was posted to France, No. 5 Squadron ‘…forbade the use of this tank for petrol, and it was kept empty. Later on I was pretty glad of this’3

Once this health and safety nightmare had been avoided, the Re8 was a welcome upgrade from its predecessor, the B.E.2c:

The R.E.8 was a faster, and more powerful reconnaissance machine than…the B.E.2c…The [B.E.2c] observer…who sat in front of the pilot…had to shoot backwards over the pilot’s head, …However, in the R.E.8 he was put in the back cockpit, which had a swivel seat and a Lewis gun mounting which he could swing around on and point in any direction..The pilot was also given a Vickers machine gun which was synchronized to fire in a forward direction through the propeller, but he didn’t often have the chance of using this, because his plane was too slow to catch up and get on the tail of the German Scouts. It was used mainly for “strafing” the enemy troops in the trenches.

Actually the change over made the observer the rear gunner, and incidentally helped tremendously in re-establishing the air ascendancy for the Allies at any rate, adjacent to the front line. The operations such as photography, artillery spotting, and ranging for our batteries, and various other patrol duties were carried out with much greater freedom from attacks by enemy aircraft. Of course, the real credit of winning back the air ascendancy must be given to the Scout Squadrons, Sopwith’s and S.E.5’s etc., that operated many miles inside the enemy territory, and “shot up” enemy aircraft as they were taking off from their own aerodromes.

‘A flight of Australian Scouting Machines, Sopwith Camel fighter aircraft…’ of No 4 Sqn, AFC. Source: AWM E01877

‘A flight of Australian Scouting Machines, Sopwith Camel fighter aircraft…’ of No 4 Sqn, AFC. Source: AWM E01877

Allport mentions that when Re8 pilots sighted an enemy scout, they would usually fly back to the safety of their own lines, ‘until he went away.’ In time the German fighters became reluctant to attack unless they had the element of surprise:

…because an R.E.8 properly handled, with a good crew, was equal to at least two German scouts. The attack by the scout invariably came from the rear, and by banking at more than a 45º angle, the R.E.8 pilot could control his flying, and by pulling the stick back, the turn could be regulated in such a manner as to keep the attacker in full view of the gunner, without the former being able to retaliate. The only advantage the German had was being the faster plane, he could break off the fight at will, and maintain his height more easily.

1. Aerial opposition:

Lone wolves and flying circuses

Albatros D.V.scouts of Jasta 5. ‘It was a very neat looking German scout plane painted in a black and white check pattern.’

Albatros D.V.scouts of Jasta 5. ‘It was a very neat looking German scout plane painted in a black and white check pattern.’

When asked about the German air opposition Allport recalled:

We were mostly bothered by the “lone wolf” who, on a cloudy day, would sneak up and catch you unawares.

He described one such encounter:

It was a very neat looking German scout plane painted in a black and white check pattern. It was a day with big billowy clouds down to about 4,000 ft. and the E.A. evidently had spotted us from a greater height and worked out his dive around the edge of the cloud.

My trusty observer had seen him coming, and I only woke up to the fact, when I heard him firing a burst from his machine gun at the Hun. I banked to prevent the enemy from getting a sight on us from behind, and by good luck more than good management, we had him where we wanted him, and as he persisted in trying to dive under our tail, I prevented this by pulling the plane into a steeper and tighter turn, meantime he was being raked by my observer’s fire.

Having greater speed he was able to break off the attack, and as he did not return we were able to finish the shoot in comparative peace.

On another occasion on a photographic mission deep into enemy territory they had an escort of 4 Sopwith Triplanes from No.8 Naval Squadron:

Triplanes of No. 1 Naval Squadron at Bailleul, France

Triplanes of No. 1 Naval Squadron at Bailleul, France

…we set out with complete confidence and rendezvoused with the “Tripes”. …In this instance, my particular photographs were to be taken some distance over the line. What I didn’t know at this time was that the escort was flying many thousands of feet above us while I was busy taking the photographs.

It was a very nice warm day, the sky was clear, the sun was shining, and I think that with the rarified atmosphere, my observer must have gone off to sleep. The result was that a wily lone flier came in. to the attack, and he got a pretty good burst of machine gun fire into us whilst I was busy concentrating on aiming for the photographs. The machine gun fire came in from pretty close range, and consequently by instinct, I kicked the rudder and yanked the joystick, and I think that the result of our peculiar manoeuvre must have convinced our attacker that he had achieved a kill. Anyway, I side slipped some height off and circled, but as he didn’t return to the attack, we were able to hurry at full bore back to our own lines, and as the saying goes, live to fight another day.

It wasn’t just the lone wolves that they had to worry about:

I developed a very keen eye for spotting enemy aircraft before they got too close. Actually the enemy took great exception to photographic patrols, and they very often sent up “Circuses”’ to intercept, and, of course, it didn’t take very long to determine whether they were enemy aircraft or not, we could very quickly do that.

We would quite often encounter the Albatros, Pfalz, D.F.W.‘s and in the latter period, the Fokker Triplane.

Line-up of Fokker Dr1s from Jasta 26 at Urchin, France. Source:Wikipedia

Line-up of Fokker Dr1s from Jasta 26 at Urchin, France. Source:Wikipedia

2 Squadron: FK.8s

Allport was transferred as a flight Commander to No. 2 Squadron, commanded by Major Wilfred Snow,4 from Adelaide:

This Squadron was equipped with the big Armstrong Whitworth [Fk8] which we knew as the “Big Ack” or “Ack W” and although it was more cumbersome than the R.E.8 it was more powerful and had a water-cooled Beardmore engine…The “Ack W’s” were a very strong plane which could take a bit of punishment, and had all flying wires duplicated. The large wingspan enabled it to carry a pretty good load of bombs, which we used to do quite frequently on moonlight nights.

…Actually, the big Armstrong Whitworth could take care of itself providing you had a reasonable crew in it. It was very similar in layout to the R.E.8 in that the gunner, or observer, had a swivel mount fitted with a single, or a double Lewis gun, and the pilot had one forward firing gun.

‘the [Fk8.] “Big Ack” or “Ack W”…although it was more cumbersome than the R.E.8 it was more powerful’

‘the [Fk8.] “Big Ack” or “Ack W”…although it was more cumbersome than the R.E.8 it was more powerful’

Allport flying, Hammond gunning.

“…On a later occasion, whilst on photographing work, he was attacked by six enemy machines, but by skilful manoeuvring he enabled his observer to shoot down in flames one enemy machine, another falling to pieces in the air…”

An air battle with ‘ace’ observer Lt. Arthur Hammond earned both men citations:

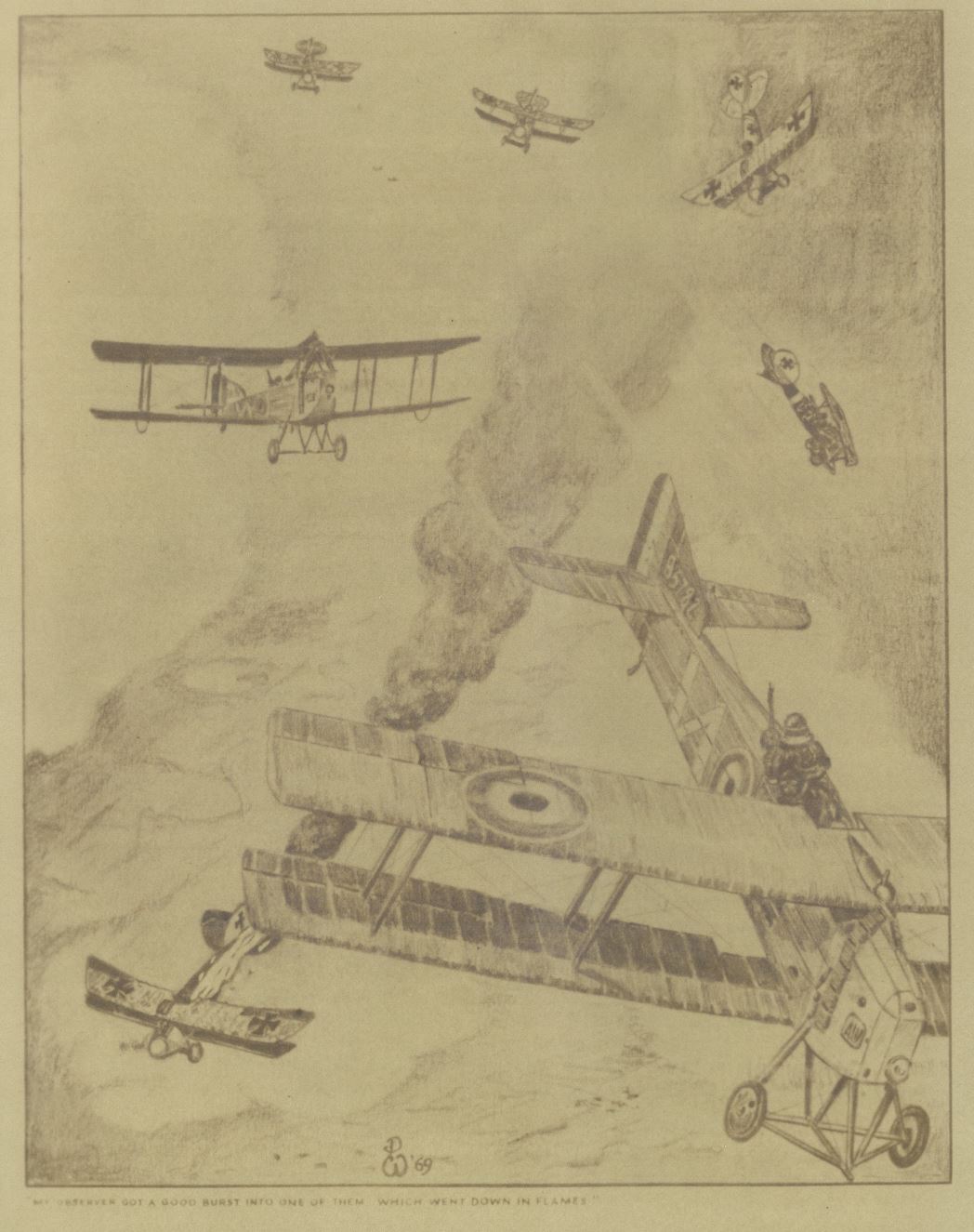

It was the beginning of 1918, and the German “Circuses” were making their appearance up north where we were. On one occasion, on photography, in company with another Armstrong Whitworth which was acting as my-escort, we ran slap bang into a brightly coloured “Circus” of six Albatros, which dived almost vertically at us. My observer, Arthur Hammond, a Canadian who saw them first, got a good burst into one of them, which went down in flames. From then on it was a dog-fight between the Germans and the two of us, during which time I circled many times, keeping a watch on my tail. As each one came at us, we pulled into an increasingly tighter turn, and “Hammy” my observer, would have his gun trained on the enemy aircraft, as long as they would persist in trying to get on our tail. One of these he also shot down, and by this time we were down to about 500 ft. and there was only one of them left to chase off. He eventually made off after a burst of fire from “Hammy”, and at last we had a chance to open the throttle and take for home, and our side of the lines.1

‘My observer, Arthur Hammond, a Canadian who saw them first, got a good burst into one of them, which went down in flames.’ B&W illustration by Derek White. (Signed DW’69) Reproduced with permission from the Australian Society of WW1 Aero Historians

‘My observer, Arthur Hammond, a Canadian who saw them first, got a good burst into one of them, which went down in flames.’ B&W illustration by Derek White. (Signed DW’69) Reproduced with permission from the Australian Society of WW1 Aero Historians

Our escort was okay, having also lost height in the scrum. I fired a Verey light, indicating to him to get back into formation, and having regained our height, we were able to go over and secure our photographs without being molested again.

Major Wilfrid R. Snow, (Jack Allport’s 2 Sqn. C.O.) recalled later:

Among others, I had ‘Sayers’ Allport, of Sydney, a splendid fellow. He was attacked one day, when he was in a slow old ‘bus’, by five German scouts, whose machines were 50 miles an hour faster than his. But he accepted the proposition and made it willing. He shot down two, and the other three cleared for their lives. Allport just carried on, and finished his job. That’s the type of men the colonial flyers are.

2nd Lt. Seton Montgomerie’s diary recorded:

Found Hom and Broadbent had been killed on 18 Feb in a fight. In this fight, Allport and Hammond were attacked and Hammond brought two down – one in flames and this is a very good performance.2

Allport and Hammond’s action took place at La Bassée, near Armentières. Jasta 23b recorded that Leutnant Heinrich Kütt came down wounded3

L.F.G Roland D.VIa, Ltn.Otto Kissenberth, Jasta 23b,1918. Kissenberth was the commander of Jasta 23 when they engaged Allport, Hammond and shot down Hom and Broadbent

L.F.G Roland D.VIa, Ltn.Otto Kissenberth, Jasta 23b,1918. Kissenberth was the commander of Jasta 23 when they engaged Allport, Hammond and shot down Hom and Broadbent

Hammond was also involved in an aerial battle with another pilot, Lt. A.A. McLeod Allport remembered McLeod:

Yes, he was one of the pilots in my flight whilst I was over there and when I was transferred to England, he took over from me as Flight Commander, also, my observer, Hammond, became his observer.

They were in a scrap in which they were shot down, incidentally after Hammy had shot down two of the enemy aircraft of which there were 5 or 6 attacking them. They were set on fire and things got a bit hot for Hammy and Mac, so Mac got out on the wing and controlled the plane down, keeping the flames from blowing their way. They crashed into No-Man’s Land and Mac who was wounded pretty badly, dragged the badly injured Hammond out of the plane and into our trenches, under gunfire from the Germans, which again wounded him. The result of this exploit was that Mac received the V.C. and Hammy a Bar to his M.C. Hammy lost a leg, and Mac died later, in Canada, from the wounds he received in this action. McLeod was a wild sort of chap but Hammy was a cool-headed fellow, and probably one of the best shots, as far as shooting aircraft down among the observers.

F.K. 8 reportedly the machine that McLeod was flying the day he was shot down. It was destroyed in the crash.

F.K. 8 reportedly the machine that McLeod was flying the day he was shot down. It was destroyed in the crash.

2) A typical day in the front office: Artillery observation, photography and night bombing missions.

“…On several occasions, he has carried out his tasks of photographing hostile battery positions and calibrating our long-range batteries on their targets under the most unfavourable conditions and with the excellent results, showing a magnificent example to the whole squadron…”

Allport and Observer. Reproduced with permission from the Australian Society of WW1 Aero Historians

Allport and Observer. Reproduced with permission from the Australian Society of WW1 Aero Historians

‘Art. Obs.’

Allport described how aircraft were used to spot German positions and direct artillery fire onto them:

Most shoots were pre-arranged with the batteries, targets being mainly gun emplacements. All known gun emplacements were registered on a counter-battery map which was prepared by the intelligence department. The procedure was to call up the battery by wireless, they, in turn, would put out a large white ground signal when they were ready to fire. The pilot usually flew towards the battery signalling “G” on his transmitter, (Morse buzzer) and watching for the flash of the gun. Then he turned towards the target watching for the burst, which usually occurred 20 or 30 seconds after firing. Corrections were sent down, and each gun of the battery individually ranged. The shoot was successful, or termed successful, when the battery was satisfied and put out the appropriate ground signal.

Three hours would be the average time of the shoot during which time, as you may imagine, the pilot had plenty to do in addition to keeping an eye open for enemy aircraft. When they appeared it was better to stop the shoot for a while and retreat to one’s own side of the line. The enemy aircraft were quite often spotter planes locating our batteries, or scouts after our blood. We were equipped with forward-firing guns, but obviously, we could not bring them to bear on a faster flying machine. The Artillery observation machines were too slow even to catch up with an enemy scout or get on his tail.

Haubourdin, France. 1918-10-17. Aerial photograph of smoke billowing from hangars set on fire …

Haubourdin, France. 1918-10-17. Aerial photograph of smoke billowing from hangars set on fire …

Aerial Photography

Allport flew at about 5,000 ft. for artillery observations and photography missions, except on one occasion:

…whilst I was still a bit green I was given the task of photographing certain gun positions and it looked like being a sticky job. Not knowing what height to go over at, I asked the Photographic Section from what height they would like the photographs taken. Curiously enough they said that they liked them taken from a height of about 2,000 ft. So, having been given the positions and locations of a number of gun emplacements, I proceeded over the line at an altitude of 2,000 ft., with the result that I got some very good photographs, even showing the actual guns in their emplacements.

But I also got a good collection of holes in the aircraft from machine gun fire from the ground, for our repair department’s attention. As a matter of fact, one bullet passed through the engine oil pressure pipe, and another entered the petrol tank. The observer and I were both well saturated with petrol and oil, but fortunately, we didn’t experience any fire. However, the plane got us back to our side of the line, and we were able to get it down into a paddock all in one piece, although the engine was very sick, and had, in fact, seized up by this time, being on full throttle.

German anti aircraft shrapnel bursting near an Australian RE8 aeroplane.

German anti aircraft shrapnel bursting near an Australian RE8 aeroplane.

Night bombing

“On one occasion during night flying he made four trips during a period of four hours, dropping sixty bombs on his two objectives with excellent results…”

Bombing at night was considered less dangerous than during the day when the German scouts were prowling the skies:

The night flying was not too difficult, and our casualties were very few. We operated from a larger aerodrome because Hesdigneul had very limited space, this aerodrome being Auchel. Incidentally, we were briefed very thoroughly beforehand on finding our targets, and, of course, on getting home again. The main guides to memorize were canals, in which the moonlight and stars would be reflected in the water, long tree-lined roads, and the various peculiar shapes of the numerous woods, and copses, in this area. We knew these like the palms of our hands, from our day flying, and we had no instrument aid except the compass which on its own was of very little value. For landing, at night each plane was equipped with a magnesium flare, which was attached to the underside of the wings. When coming into land this was ignited by the pilot, by remote control, and incidentally was very effective

‘Archie’

German Anti-Aircraft gun and crew. ‘Opposition to our actions would then be put up by the enemy in the form of machine gun tracers, and another missile which we called the ‘Flaming Onion’. This was similar as its name suggests, to a string of onions, there would be about 20 of these things all strung together, and they were like flaming balls, and were very spectacular. I have never heard of a plane being hit by one, or what the result would be.’

German Anti-Aircraft gun and crew. ‘Opposition to our actions would then be put up by the enemy in the form of machine gun tracers, and another missile which we called the ‘Flaming Onion’. This was similar as its name suggests, to a string of onions, there would be about 20 of these things all strung together, and they were like flaming balls, and were very spectacular. I have never heard of a plane being hit by one, or what the result would be.’

Anti-aircraft fire was an occupational hazard, but the Re8 and Fk8 crews carried on:

Well, by and large, anti-aircraft fire didn’t bother us very much, except when straight flying on photography missions, or when in formation. Most counter battery shoots were done from just on our side of the line, at approximately 5,000 ft., and the “Archie” virtually never ceased, but it was only the very occasional piece of shrapnel which left its mark on the plane. The avoiding technique in this regard was to develop a habit of constant change in direction, and a variation in height.

I believe that very few of our artillery observation planes were shot down by enemy anti-aircraft fire although, I believe it used to worry our scout pilots when flying in formation over the lines. It actually had the effect of keeping them up high, which obviously made them a harder target to hit. In another respect, it is possible that our bombers who penetrated further over the lines, would avoid certain areas or towns where the anti-aircraft batteries were known to be concentrated with a consequent increase in anti-aircraft fire. But the art-obs planes, as I say, having developed the habit of evasion, were not bothered very much, although there might be the odd shot that may come near us.

Footnotes

1 RFC Communiqué No 127: February 18; Enemy aircraft – Capt. J Allport and Lt. A W Hammond, 2 Squadron, while on photography, were attacked by six EA scouts. Lt. Hammond shot two down; one burst into flames and crashed, the other fell to pieces.

RFC Communiqué No 129: March 1; Honours and Awards, The Military Cross – Capt. J M Allport; Lt. A W Hammond

2 ‘No 2 Squadron RFC 1918, Lt Montgomerie’s diary’ http://www.hsm.airwar1.org.uk/hsm2.htm retrieved online 14/12/18

3 Guttman, John ‘Alan McCleod’ espritdecorps online July 18, 2018 No. 2 Squadron lost Lieutenant Alfred Jones Homersham and Captain Sydney Broadbent, both killed in B211 by Bavarian Jasta 23’s Leutnant Max Gossner at Armentières. Source: Ibid.

3 ‘One bullet which must have gone close to myself or the observer went into the front petrol tank, but thanks to the squadron orders, which I mentioned previously, the tank was empty. However, a thin stream of smoke came from it, and this pretty well continued all the way home, evidently this bullet was a phosphorous tracer. There was no actual fire but, as I say, had that tank been full of petrol, or even petrol fumes, which they did have in training in England, it would probably have been a completely different story.’

4 Located at Hesdigneul, near Bethune, and operated on the Lens front. After about 200 hrs of flying over the front (from 22nd May to the 10th August 1917)

Follow the J.M. Allport story in the following articles:

Fledgling wings: Lt. Taylor inspires Gunner Allport.

The high flying (and diving) Capt. Jack Allport.

Capt. Allport, MC: Air war over the Western Front

Capt. J.M. Allport: ‘Aerial Reconnaissance on the Western Front’