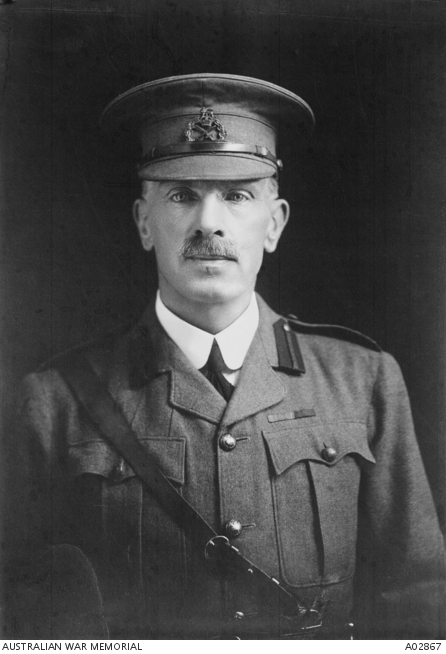

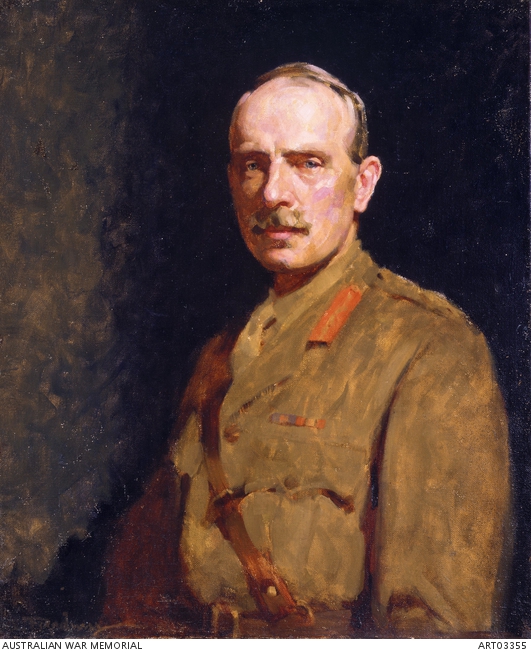

Studio portrait of Major General Sir William Bridges KCB CMG. Photographer: Alice Mills, Melbourne. (AWM A02867)

Anyhow, I have commanded an Australian Division for nine months…

These were the reported last words of Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges. According to C. E. W. Bean1, he knew he was dying.

A few days earlier, Bridges had been picked out by a sniper in Monash Valley. The lone bullet cut his thigh artery.

Gangrene soon set in. His doctors aboard the hospital ship Gascon, knew amputation for the 53 year old would be fatal. Nature took its course and William Bridges died three days later en route to Cairo.

Bridges last recorded instruction was,

that his regret should be conveyed to the Minister for Defence that his dispatch concerning the landing was not complete — he was too tired now.

We can only surmise as to the mental processes of this proud man as he slipped in and out of consciousness. He may have remembered his life experiences, or those closest to him. Memories of time spent with his family and friends around Sydney’s foreshores. In particular his posting to Middle Head.

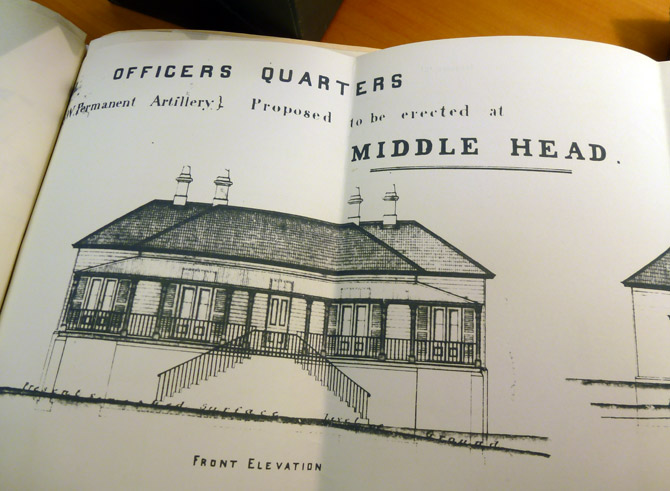

The Officers Quarters later Permanent Married Quarter No. 9 at Middle Head. Bridges lived here with his family from 1886-1893 when he was Officer Commanding Middle Head Battery.

C.E.W. Bean takes up the story.

Bridges … was in charge of the coastal batteries on Middle Head in Sydney Harbour. These were a part of the port defences and sited so as to fire on any hostile craft trying to enter between North and South heads, about a mile away. The task of preparing for that event was not an inspiring one, and the little group of buildings in the bush on Middle Head, connected only by a track with the then sleepy, scattered suburb of Mosman, might have been an isolated country post. There was no stimulating friends, little work, and apparently slight chance of progress in the small colonial force. Bridges’ main occupations during the idle months at Middle Head were reading novels and sailing.2

As he lay in waiting for the end, his thoughts may have turned to family. Edith his devoted wife of 30 years…all those times he’d made her anxious sailing outside the Heads with the commander from Watson’s bay.. His eight children. Four of whom had died young.

One had drowned at Chowder Bay in a tragic boating accident. She was on the way to her seventh birthday party, with her twin sister. Donald, the apple of his father’s eye, his early death, a dreadful blow.

Bridges had seen eldest son Francis Noel for the last time en route to Cairo, on the Orvieto. Noel had been born in Mosman whilst he was on duty at Middle Head.

Bridges was sitting on deck reading a newspaper when someone tapped it. It was his son Noel, who was traveling by a British ship from Singapore to London to enlist. They were delighted to see each other, but if, as is possible, Noel sought some way of joining the Australian force, he was disappointed3.

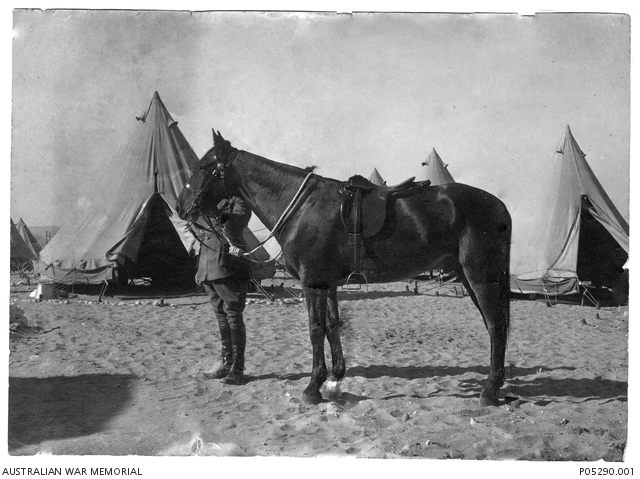

Bridges holding the bridle of his favourite charger, Sandy. The horse is a 15.3 hands high bay gelding with a white star. They are standing in front of the tents of the 1st Australian Division at the Mena Camp, Egypt, prior to embarkation to Gallipoli. (AWM P05290.001)

During his professional career Bridges remained aloof from personal connections. He was however, fond of horses, especially his personal mount , Sandy. Of the 121,324 horses sent abroad during the First World War, Sandy was the only one to return4.

Sandy followed the gun carriage when Bridges was buried among his soldiers at Alexandria. Later that year Bridges body was brought home. On 3 September 1915, the respected commander was given a solemn military state funeral in Melbourne. Afterwards his body was taken to Canberra for burial. People lined the streets and railway towns along the way. The procession became a public display of private grief and anxiety. For sons, brothers, fathers and uncles overseas.

Canberra, 3 September 1915. The burial of Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges, KCB, CMG, Commander of the Australian Imperial Force and of the 1st Australian Division. With the exception of the Unknown Australian soldier re interred at the Australian War Memorial in 1993, Major General Throsby was the only Australian to die overseas during the First World War and be re interred on Australian soil. (AWM P10797.002)

Bridges’ grave is now a permanent monument at Mount Pleasant

His tombstone bears the words ‘A gallant and erudite soldier.’

It overlooks Duntroon, an institution he was instrumental in founding. The Royal Military College is based on the West Point and Sandhurst academies. Bridges was its first Commandant. At Duntroon he became a Brigadier General, the first Australian to do so.

Bean notes that Bridges was always media shy. On one occasion however, he called the official correspondent over. Bridges made the point that artillery observers on the first day of the Gallipoli landings were Duntroon graduates. He was proud of the fact.

25 September 1914. The original 2nd Infrantry Brigade passing Parliament House, Melbourne. This brigade was part of the 1st Australian Division which, with the 1st Light Horse Brigade, formed the first contingent of the AIF to be sent overseas. Behind the Governor-General (in dark uniform) and Colonel the Hon J W McCay (with sword) are standing Major-General Bridges and the staff of the 1st Australian Division. (AWM J00352)

Bridges’ other major achievement was the organization and recruitment of the 1st Australian Imperial Force. Bean describes the how the force was named at the 1st staff meeting.

About a dozen titles were suggested by those present “Too long!” he said to some of them. I want a name that will sound well when they call us by our initials. That’s how they will speak of us. We don’t want to be called B.U.M.F!” He himself suggested Australian Imperial Force. Though the day had not yet arrived when every military institution and many civil ones were tagged with capital letters, his foresight was as usual sound. By the letters A.I.F the force which he founded became known throughout the Empire.

Bridges was promoted to command the A.I.F. There is no evidence, according to Bean, that he sought the position. In fact, he’d recommended someone else.

On paper Bridges was the man for the job. He had a background in civil engineering, expertise in artillery, gunnery and intelligence work. His organizational skills, drive and ability to appoint competent staff made him a worthy candidate.

At times he was cold, brusque and unappreciative of those around him. Sir Cyril Brudenell Bingham White, fellow founder of the A.I.F. and present on Bridges’ staff at Gallipoli, said:

He lacked just the little added touch which would have made him a big man. But he was a big soldier… General Birdwood has told me he came to value his advice and to depend on it. He was always thinking, and was independent enough to think for himself, and strong enough to hold his own view when others held differently.

On the evening of the landing at Gallipoli he and NZ Maj. Gen. Godley would have to advise General Birdwood about the situation at ANZAC. He did not shrink from presenting Birdwood with their grim assessment.

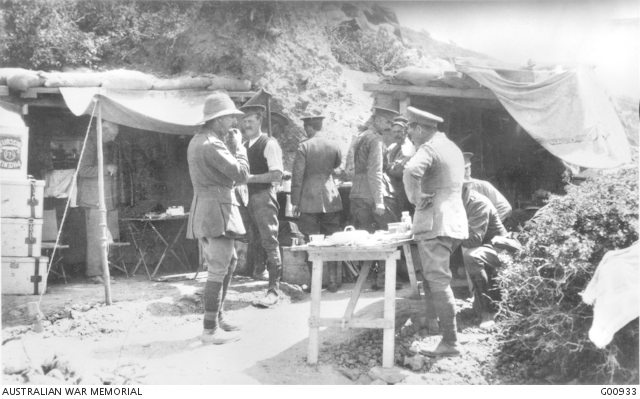

3 May 1915. At General Bridges’ first Headquarters at Anzac, during lunch. The officers in the photograph, reading from left to right, are General Bridges, (in dugout); Lieutenant Riches; Private Wicks (Batman to General Bridges); Captain Foster (Aide-de-Camp); Major Gellibrand; Colonel Howse; Major Blamey; Colonel White; Major Wagstaff. The position was exposed to shrapnel fire and Major Gellibrand was wounded there. (AWM G00933)

Bridges had pushed the troops to breaking point at their training camps in Egypt. However, Bean says they were genuinely shocked by his death. He had earned their respect with his daily visits to the front line.

Overall Bridges remains a bit of an enigma. Bean gives this interesting insight, from the music room of the Orvieto after dinner.

Nothing pleased Bridges more than a brief discussion over a knotty point. At his table at dinner, to which he invited members of his staff in turn, I happened to say that long words were too often resorted to by writers either from haziness or laziness – to avoid the trouble of thinking out what they meant; it should be possible, I contended, to express almost any thought in words which a nursemaid would understand. “How would you write this then?” he retorted, rolling off at once three or four labyrinthine lines from an English version of the Critique of Pure Reason or some other of Kant’s philosophical works. Unfortunately I kept no note of the passage or of the attempted solution which I handed to him the next day.

May 1915. The main track up Shrapnel Gully on the Gallipoli Peninsula, showing traverses, built to provide cover from Turkish snipers. It was near this site that Bridges was mortally wounded. Pope’s Hill can be seen in the background. (AWM C02676)

Bean concludes that Bridges’ habit of exposing himself to danger made it unlikely that he would survive many months of fighting

Had he done so, it is probable that he would have emerged the greatest of Australia’s soldiers, as he was certainly the most profound of her military students.

Bridges was awarded a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) in 1909, and the day before he died a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB), and was twice posthumously mentioned in despatches.

The family home “The Mill” in Moss Vale was converted into a convalescent hospital for returning servicemen in 1916.

A posthumous portrait of Bridges by Florence Rodway (AWM ART03355)

Follow Maj. Gen. Bridges story…

An audience with the Sphinx: Maj. Gen. Bridges at ANZAC, 25th April, 1915

Burning Bridges: ANZAC in hindsight, 100 years on

Articles about the August offensives at Gallipoli.

Hill 60 and the lost 18th. Aug. 22, 1915

Hill 60 and the lost 18th. Aug. 27, 1915

Remembering Major T.H. Redford, at The Nek

References

Bean, C. E. W. (Charles Edwin Woodrow) 1957, Two men I knew / William Bridges and Brudenell White, founders of the A.I.F., Angus and Robertson, Sydney

Ricketts, H G, History of Middle Head Barracks at Mosman, NSW, plus a chronological biography of William Throsby Bridges. Includes copies of plans of military surveys of the area and buildings. Manuscript, MSS0762, Australian War Memorial

Clark, Chris, Bridges, Sir William Throsby, Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 7, (MUP), 1979

Major General William Throsby Bridges, Australian War Memorial

Anzac centenary: Anniversary of the death of Major General William Throsby Bridges, ABC News, 18 May 2015

Who’s Who – Sir William Bridges, firstworldwar.com

Guide to the Papers of Major-General William Throsby Bridges, KCB, CMG

Ziino, Bart, Mourning and commemoration in Australia: The case of Sir W.T. Bridges and the Unknown Australian soldier

Coulthard-Clark, Chris, One came home / The waler’s tale touched a nation, but the facts are coloured by wistful fiction…, Wartime, Issue 19

Penhallow, Ann, Charging Home, AWM blog, 19 August 2008

Notes

1 Unless otherwise noted, quotes are from C. E. W. Bean’s book Two men I knew.

2 Bridges’ pace of life was soon to pick up as he left this backwater idyll. “In 1891 there had occurred a sudden change in this hitherto purposeless life at Middle Head. The Government decided to turn this little station into a school of gunnery. Bridges was sent to England to attend the long course… He took his wife and family with him… It was a turning point in his career. He threw himself into his work with an impulse which never again relaxed.”

3 Noel continued on to London where he enlisted in the Royal Engineers and then received a commission in the Northumberland Fusiliers. Bean noted that Noel like his father “feared nothing and was determined to make his own life” — this included joining the ranks of his fellow countrymen. “After his father’s death six months later he applied for permission to be transferred to the A.I.F and became one of the very few men allowed to join it in England. He served on Gallipoli and on the Western Front, ending up his fine service there as a brigade-major of the 7th Infantry Brigade.” Noel Bridges was awarded a Distinguished Service Order (D.S.O) and was Mentioned in Dispatches (M.I.D) in 1917. After the war Noel Bridges returned to Malaya with his wife and was eventually made Surveyor General of the colony and Director of Military Surveys when war broke out in 1939. As Singapore fell he was ordered to go on duty in Java. “After a perilous journey of ten days,” writes Bean, “they reached Padang in Sumatra. They sailed thence in a small Chinese vessel, but were never heard of again.”

4 “As the official record says, [Sandy] was “pensioned off”, or turned out to graze at the Central Remount Depot in Maribyrnong. Blind and unwell, Sandy was put down in 1923.”

Appendix: Description of Bridges shot by a Turkish sniper by C.E.W Bean.

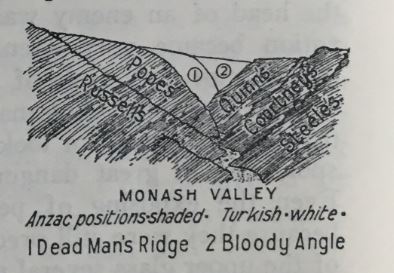

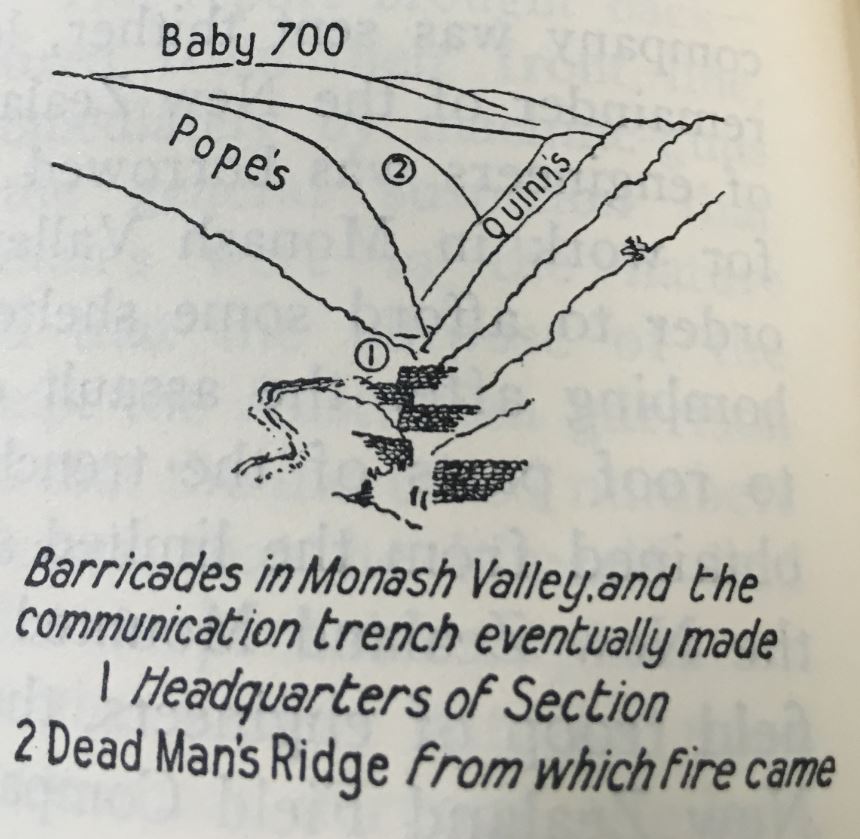

sketch by C.E.W. Bean

Exerpt from C.E.W. Bean’s Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 Volume II – The Story of ANZAC from 4 May, 1915, to the evacuation of the Gallipoli Peninsula CHAPTER IV: THE PROBLEM OF MONASH VALLEY p.128-30

As, however, the fighting crystallized into trench-warfare, in which-except at such exposed points-the figure or even the head of an enemy was rarely seen by either side, observation became very keen. Such signs as smoke, or the throwing of shovelfuls of earth on to the parapet, were likely to draw shell-fire. Any man peering over the parapet for more than a few seconds, or looking out several times from the same spot, was in great danger of being shot through

the head. Even the exposing of periscopes needed caution, not only because they were still precious, but because by the splintering of the upper glass several men were injured in the eyes. Both General Bridges and General Walker constantly had their periscopes struck, and on May 14th General Birdwood, when looking through one at Quinn’s, was grazed on the head by part of a bullet deflected from the upper mirror.

Early on May 15th, in the morning following the attack by the 2nd Light Horse, the sniping down Monash Valley, in spite of the traverses, became severe. Several men running between those barriers were hit. It happened that on this morning Bridges had asked permission to visit Chauvel’s headquarters in the valley, which was in the N.Z.& A. Division’s sector. As he went up the road with Colonel White and Lieutenant Casey (his A.D.C.) they met Major William Glasgow, of the 1st Light Horse Regiment, with some of his men on their way down.

“Be careful of the next corner,” he said, “I have lost five men there to-day.’’

Such warnings, which were constantly heard by anyone visiting the trenches, were usually little heeded. But this particular officer was not one who would give idle advice. When, therefore, they reached a traverse 200 yards below Chauvel’s headquarters, and some men behind the next barrier advised them to run to it, General Bridges, to the surprise of his companions, adopted the suggestion. His ordinary practice had been to expose himself without regard for danger, laughing down at his staff when they took cover, and asking “what they were getting down there for?” But he had apparently begun to realise that this impunity could not continue.

sketch by C.E.W. Bean

On this day, probably guessing from a certain vague tension in the valley that the danger was real, he acted upon the advice tendered The party ran three or four times between barriers, until they reached the one below Steele’s Post. Behind this was the dressing-station of Captain Thompson of the 1st Battalion. After talking a few minutes and lighting a cigarette Bridges went on, Thompson warning him to be careful. The general’s long legs disappeared in the scrub round the traverse, and the others were preparing to follow, when there was some sort of stir, and Thompson ran out to find Bridges lying with a huge bullet-hole through his thigh. Both femoral artery and vein had been cut, and, though Thompson instantly stopped the bleeding, the loss of blood had been very great. As they brought the general back into the shelter of the traverse, strangely changed from the bronzed healthy man who had passed a few seconds before, he said weakly,

Don’t carry me down – I don’t want any of your stretcher-bearers hit.

Colonel White had the traffic in the gully stopped, so that it should be clear to the Turks that the only movement was the carrying of a wounded man, and then the party moved slowly to the Beach. The Turks, whether by accident or by a forbearance which they sometimes showed, did not fire upon it. Bridges was taken at once to the hospital ship Gascon. But the whole blood-supply to the limb had been cut off, and nothing could save his life except complete amputation at the thigh, an operation which, it was considered, to a man of his years, must prove fatal. Before the Garcon left for Alexandria he knew he was dying. “Anyhow,” he said to Colonel Ryan,

…anyhow, I have commanded an Australian Division for nine months.

He died before the ship reached port. His body was brought to Australia and buried on the hill above the military college at Duntroon, which he had founded.

Bridges’ habit of exposing himself to danger had made it from the first unlikely that he would survive many months of fighting. Had he done so, it is probable that he would have emerged the greatest of Australia’s soldiers, as he was certainly the most profound of her military students. His powerful mind and great knowledge were supported by outstanding moral and physical courage, and also by a ruthless driving force, rare in students. Only in Haig and Allenby did Australians meet any commander whose forcefulness equaled that of Bridges. His defect as a leader-the inability to display those qualities which would make the ordinary man love and follow him-was finding its compensation in the conspicuous bravery with which, since the landing, he had won the admiration of the troops.

Upon Bridges’ death the command of the 1st Australian Division temporarily passed, in accordance with the general expectation of those at Anzac, to Brigadier-General H. B. Walker, of the 1st Infantry Brigade, an officer who, by his directness, his fighting qualities, and his consideration for his men, had in a few weeks much endeared himself to the troops.