The 18th Battalion’s recruits from the Sydney area (including Mosman) were described by official war historian C.E.W Bean as ‘great big cheery fellows, whom it did your heart good to see.’ Within 48 hours of landing at Gallipoli, 50% of them were either dead or wounded. A few days later, 80% of the 760 men who started the battle had become casualties.

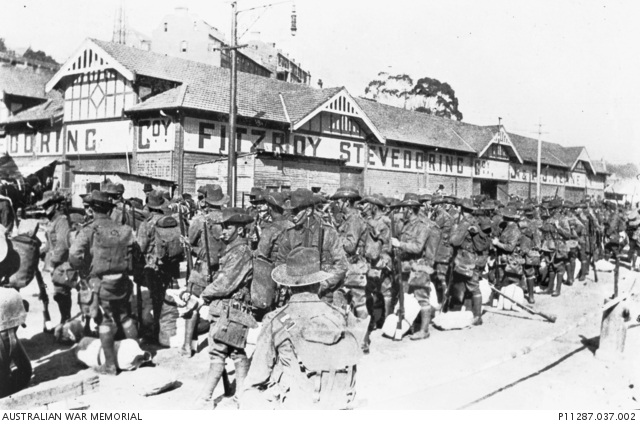

Men of the 18th Battalion waiting at the wharf to embark on the troopship A40 HMT Ceramic. ..From an album relating to the service of 1248 Sergeant Roberts, 18th Battalion, later Lieutenant Roberts, RFC.

Nights on the Nile

The 18th Battalion shipped out for overseas service in May, 1915. Corporal Joseph Maxwell of ‘B’ Company found their destination far less exotic than he’d imagined

Egypt!

Historic dust of tombs and crumbling stone, fleeting pictures of Cleopatra and Rameses in the back of the brain, glamour, colour, romance. How it all surged through the mind as the Ceramic nosed her way into the entrance of the Suez Canal. But once again my mental pictures were shattered…Scented, sensuous, nights on the Nile. What did they become? Blasted seared caricatures of the pictures I had conjured. A stifling heat that seared the brain, a penetrating desert dust that scraped the flesh, sweat, boots, thirst, utter weariness, swish of sand, and the flame that poured from the sun and made men mad.1

‘Joe’ Maxwell had nevertheless expanded his ‘gallery of good pals’ enroute. His new mates included ‘Doherty’ and ‘Mick’:

Into the 18th Battalion blew Doherty…Worries, reflection, introspection he scorned…each minute a crowded atom of life, triumphant and arrogant, that was Doherty’s code…A lumbering care free Irish-Australian, with a heart of gold, whose very presence was a vitalizing force..

Mick lacked Doherty’s effervescence but not his robust courage…The war had to be won. Of that Mick was convinced…But he failed consistently to appreciate the part that saluting “brass hats” and gentlemen with “pips”- and-things was to play in giving us victory…

They could agree on one thing though:

Both he [Mick] and Doherty gloried in their allegiance to beer- amber, froth-crusted beer, the nectar of the gods, the most seductive of mistresses…

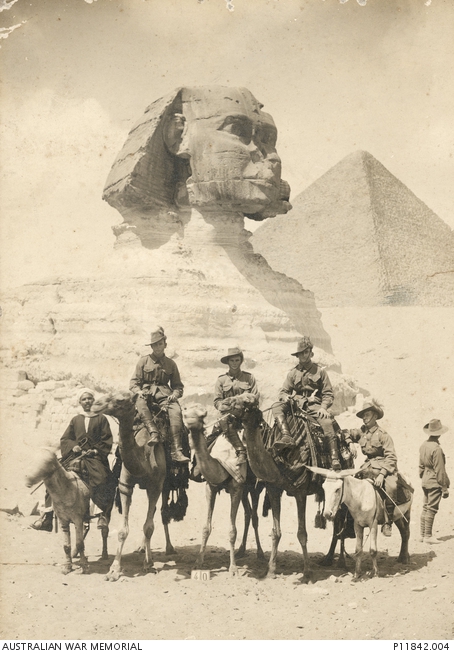

Members of the 18th Battalion in Egypt,1915

Members of the 18th Battalion in Egypt,1915

Postcard sent home by Joseph Edward Crew Source: Barry’O Keefe Library ‘Trace’ digital archive. Ken Nugent, Joseph Edward Crew’s nephew, lent for copying for the ‘Doing our Bit: Mosman 1914-1918’ project.

Blowing off steam: in bars, cafes and houses of ill repute; sightseeing at the Pyramids and souvenir-hunting helped alleviate the ‘monotonous thraldom of the desert’2 and camp life.

Maxwell described how, on one occasion trouble in the the red light district boiled over into a full-blown riot.

In Cairo I had my first fleeting glimpse of “active service” I stumbled into the fringe of the battle of Wazir. It was fast and furious … cushioned bowers of lechery [were] torn open to the general gaze, a swirl of dust and flying arms and dark faces, a crackle of “Gyppo,” a sirrocco of oaths sizzling and spluttering. It was hatred swept up like a summer storm. Arms and clubs flew, ..Up leapt the flames as the appurtenances of hired love were scattered in blazing brands and glowing embers…At the height of the battle and through the hanging dust of that stifling day, a piano (which, if endowed with speech could tell a few torrid stories), tumbled from a high window and hurtled into the street. I missed no time getting out of the racket and missed many of the high lights in an episode that was discussed excitedly for weeks.2

Gallipoli, August, 1915

Back at Gallipoli, the Sari Bair offensives of August 1915; Chunuk Bair, Lone Pine and the Nek had all ended in failure.

Lone Pine Diorama. Source: Australian War Memorial (AWM), Canberra

The landings at Suvla had also been a disaster. The last British attacks coincided with the 18th’s landing at ANZAC Cove.

The Turks had strengthened their defenses south of Suvla. Mustafa Kemal inspected the completed trenches at ‘Hill 60.’ The wiley, battle-hardened commander had ordered more artillery pieces, just in case the British were foolhardy enough to try again.3

Mustafa Kemal inspecting the battlefield, 1915

Mustafa Kemal inspecting the battlefield, 1915

Captain Henry Loughan of the 14th Battalion noted that

On August 7 we could have taken Hill 60 and Hill 100 almost without a casualty. Now that the Turks thoroughly entrenched Hill 60 , garrisoned it strongly and arranged machine guns to sweep every foot of its surface, we were to storm it. What chance would the Turks have had of taking Hill 92 by a direct attack? None whatever; just as much as we had of taking Hill 60 from them.

Charles Bean in his Official Histories wrote that the battle for Hill 60 would become

..one of the most difficult in which Australian troops were ever engaged –

[it] was conditioned by the inaccuracy of the knowledge which the staff had so far succeeded in obtaining of the complicated defences of the hill.The simple method which was applied a few years later-that of sending an aeroplane to photograph the region from above-does not seem to have suggested itself, and the local staff based its maps upon what it could see from the front line on Damakjelik and from the Suvla area. But the hill was clothed with scrub four feet high, through which the trenches were difficult to trace.

Anzac Cove, Ari Burnu:GERMAN AERIAL RECONNAISSANCE PHOTOGRAPHS OF GALLIPOLI, 1915-1916; SANDERS LIMAN VON (GENERAL) COLLECTION, 1915 Source IWM

Anzac Cove, Ari Burnu:GERMAN AERIAL RECONNAISSANCE PHOTOGRAPHS OF GALLIPOLI, 1915-1916; SANDERS LIMAN VON (GENERAL) COLLECTION, 1915 Source IWM

Darkness before the dawn

After midnight on August 21st, the 18th Btn. disembarked at Gallipoli. Cpl. Maxwell described landing in the inky darkness.

There behind us, on the beach, the ribbon of sighing surf flared like whites of eyes in the darkness. It may have been a Sydney beach in that terrible silent hour before the first glow of dawn.

We were on the move. .. Black ghosts in the gloom, platoons, companies of them; orders muttered in undertones, whispers, whispers, whispers everywhere. Above the black scarps frowned on us. But we were on solid earth. Life regained a little of is savour. There we straggled into line in the blackness. There was the friendly, comforting contact of shoulders and packs of men whose faces you cannot see. There were no faces. We were all just phantoms..

‘Finis’ by Leslie Hore

‘Finis’ by Leslie Hore

A view of the beach north of Anzac Cove.

.. Dominating the scene at left is the rock formation the Anzac’s named The Sphinx.

We straggled up to a gully directly behind the firing-line. Other strange figures detached themselves from the gloom. Veterans these, who knew the horror and grimness of war. Their step on the pebbles had a confident ring. But they too once passed though the mental bewilderment which then gripped me. This was a consoling fact to say the least.5

Despite apprehensions, the ‘new Australians’ were keen to find out about their surroundings. C.E.W. Bean notes:

As these men with well-rounded cheeks and strong limbs filed past the heights of which in Australia they had heard so much, they quietly but eagerly questioned other wayfarers as to the situation. They had not yet acquired the cynicism of old soldiers.In the quiet valley below Walker’s Ridge some of their officers had spoken gravely to them of their high duty in the tests they were about to face.These fine troops had made a deep impression upon all who saw them, and brigadiers, anxious to relieve or support their tired troops, looked eagerly towards “ the new Australians.”6

ANZAC soldiers awaiting replacements: Source AWM

ANZAC soldiers awaiting replacements: Source AWM

The 18th’s men thought they’d occupy trenches in a quiet sector. After a forced march in the darkness they halted. Orders were passed from one company to the next; fix bayonets, charge magazines, and extend into two lines! According to Bean

[this] was the first intimation to the troops that they were about to carry out an assault.7

Corporal Rex Boyden of the 18th Battalion recalled:

We were moving along the Ghurkas’ trench and were ordered to fix bayonets, so we knew there was to be a charge. Having been marching from 12 o’clock we were extremely tired and thirsty, for we had nothing to drink from the evening before, so we did not feel much like charging.8

The rising sun at their backs revealed a 4 ft. hedge covering their positions. Beyond the hedge their objective Hill 60, covered in scrub with its summit 400 yards away.

Looking down Kaiajik Dere showing Turkish trenches on the right and Australian trenches on the left of Dere, Hill 60 in in the centre. Suvla Bay and Salt lake are in the distance directly behind Hill 60, looking north west. One of a series of photographs taken on the Gallipoli Peninsula under the direction of Captain C E W Bean of the Australian Historical Mission, during the months of February and March, 1919.

Hill 60 at Gallipoli, which the 13th and 14th battalions AIF attacked on 21 August, 1915. A track through the scrub now follows the path of the communication trench that was dug the night after the attack. retrieved online from ‘Hard Jacka, the story of a Gallipoli legend’ by Michael Lawriwsky_ http://www.hardjacka.com/gallipoli.html

Hill 60 at Gallipoli, which the 13th and 14th battalions AIF attacked on 21 August, 1915. A track through the scrub now follows the path of the communication trench that was dug the night after the attack. retrieved online from ‘Hard Jacka, the story of a Gallipoli legend’ by Michael Lawriwsky_ http://www.hardjacka.com/gallipoli.html

Aug 22; A tragic morning

The 18th’s men might have been thinking about home. But there was no time to write to loved ones now.

Joe Maxwell revealed his state of mind passing the cliffs and crags of Gallipoli. The same thoughts might have have been racing as they prepared to charge.9

“God! what a damn fool I was to get into this.”

Frankly that was my thought. It kept hammering away at the brain. Streets, girls, colour, friends, life, civilisation, seemed dwindling memories, things lost forever. There was finality about it all…Lost souls must have felt like that as they were ferried across the shadowy Styx.

Around, faces were grim where a shaft of furtive light caught their profiles. This was the end.

Nothing could prepare them for what would happen next. After the starting whistle, 2 platoons forming the front line charged. The next 2 prepared to follow, throats dry, adrenaline pumping.

ANZACs charging

ANZACs charging

Joe Maxwell described being in the thick of it:

.. Out we went tripping and stumbling among the undergrowth. What a tragic morning it was! We had never seen a hand grenade, nor had our officers. Ridges sprang to life they began to crackle. Turkish machine-gun pellets pelted us. Rockets of dust burst and flew. That ripping machine gun rattle that we came to know so well raced up and down a ridge that loomed in the grey light ahead. Men fell in gullies and pockets. There were groans and thuds to right and left. You just held your breath and stumbled or crawled on..[with] Men writhing and dying in the livid morning light.15

Amongst them, Charles Barker a 30 year old Costing Clerk from Orlando Avenue, Mosman lay in the dirt, mortally wounded. A passing comrade later said that he had seen Charles. Charles had told him not to bother about him -he knew he was dying.

The 1st wave of the attack reached what they assumed was their objective. According to C.E.W. Bean:

As they scrambled through several gaps in the hedge on to a narrow belt of corn at the foot of the hill, they saw in the scrub, 150 yards ahead, the parapet of a newly-dug trench from which Turks were retiring up the hill. Fire was opened by the enemy, but both lines quickly gained the trench, which proved to be a deep, almost straight, sap leading far down to the plain on the left. A number of the enemy were at the moment endeavouring to scramble out to the rear. These were shot, and, on the front of the attack, the trench was captured. The men settled into it, some of them taking out their pipes and none having any notion that they were intended to go farther.10

The Turks counter

Turkish soldiers

Turkish soldiers

The 18th’s lead companies waited for reinforcement and further orders. The Turks didn’t hesitate. They poured troops down adjoining trenches. The counter-attack was on.

The left of the Australians was attacked with bombs, and at the same time a machine-gun on some slight eminence in that direction began to fire up the trench. The 18th had no bombs, and knew nothing of them. But a number of Turkish grenades were found in their sap, and by throwing some of these they won sufficient respite to enable them to pull down sandbags from the parapet and form a barricade, behind which for a time they successfully fought.

A private named O’Reilly climbed on to the parapet and, lying behind some sandbags until he was severely wounded by a bomb, shot steadily along the trench at the Turks, whose attention had been suddenly turned to supporting companies of the 18th that were now coming forward.11

The attack falters..

Turks who survived the bombardment emerged from their shelters. They fed ammo belts into machine-guns, and aimed rifles. The hillside erupted as gunfire swept the 18th’s advance.

.. at least three machine-guns in the scrub on Hill 60 were directed upon the wheat field at its foot; and a heavy enfilading fire was being poured in from the left .. where a Turkish officer with drawn sword could be seen pointing out to his men the target at which they should fire.

The next companies drew a murderous hail of lead from the enemy’s elevated positions,

The left of McPherson’s company, emerging through a large gap in the hedge, was broken while attempting to deploy.12

Turkish machine-gunners.

Turkish machine-gunners.

The gap in the hedge through which the 18th Infantry Battalion passed to attack Hill 60 in August 1915. Hill 60 is in the background and Hill 971 is in the far distance. C E W Bean, 1919.

The gap in the hedge through which the 18th Infantry Battalion passed to attack Hill 60 in August 1915. Hill 60 is in the background and Hill 971 is in the far distance. C E W Bean, 1919.

Like wheat at harvest, men were scythed down.

Other platoons issuing through openings south of it [the hedge] were met by tremendous fire, but a proportion crossed the field,

Any officer seen urging men forward became a priority target.

among them was Lieutenant Wilfred Addison, who, with dying and wounded around him, and machine-gun bullets tearing up the ground where he stood, steadied and waved forward the remnant of his platoon until he himself fell pierced with several bullets.13

One officer who by by luck or fate survived was Maj. Sydney Herring of the 13th Btn.

We were heavily laden, this made a quick dash impossible and we only got half way across when we were held up by enemy machine gun fire. ….There we were crouched behind some very indifferent cover in No mans’ land.. Our dead and wounded were lying around us in all directions, and to add to the horror of the situation our shells had set fire to the scrub and some of our wounded were being burnt to death before our eyes.

… I said ‘Come on, we will give it a go.!” And dashed on. There were two slight depressions leading towards Hill 60 and by luck or chance I chose the nearest to the Turks.. of those that took this route the majority reached their objective, ..[those].. that took the other route nearly all became casualties.14

..the attack fails

The Turkish artillery and machine gunners kept up their deadly work.

A machine-gun nest was decimating the 18th’s left flank. Major Powles directed the next companies to swing left into the teeth of the enfilade to take it out. But, as Bean notes:

This attempt was quickly shattered.

Maj. Powles threw his last last companies in:

These later lines, however, only reached the trench in fragments, and the situation of the left flank was desperate. From a point of vantage in a cross-trench the Turks were flinging bombs with Australians.

By now Powles had lost control of the battle. In the confusion,

An unauthorized order to retire had been given to some of Lane’s men, and in withdrawing over the open they lost heavily.16

Any chance for success waned with the setting sun.

At 7 o’clock the battalion was urged by a message from Russell to push on and seize the summit, but such an attempt would have been hopeless.

Fighting in the maze of trenches continued. It was desperate, chaotic and savage. In the dust and fading light it was hard to tell friend from foe. By 10 o’clock the decimated platoons were driven back. They stubbornly held onto 50 yards of trench with the New Zealanders and other survivors.17 This foothold would be the launching point for any further attack.

A queer brand of mordant wit.

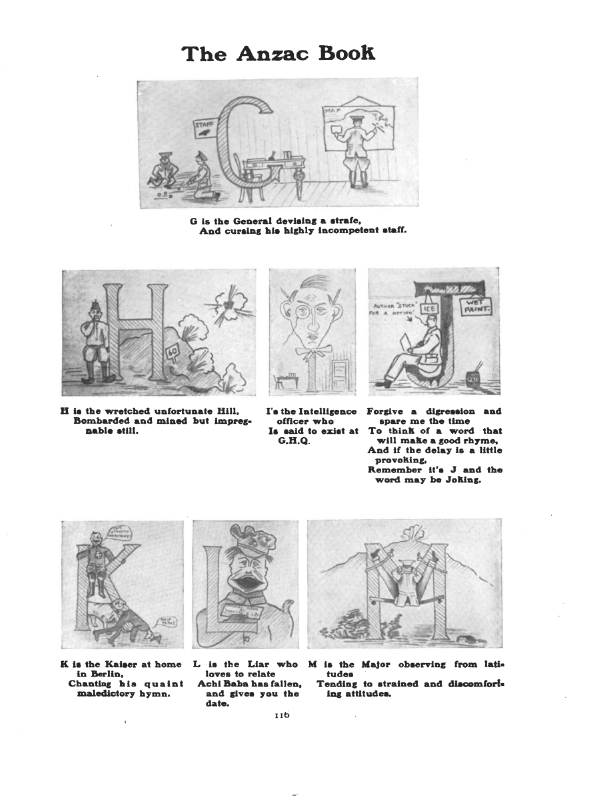

The Anzac book / written and illustrated in Gallipolli by the men of Anzac London ; New York ; Toronto ; Melbourne : Cassell, 1916 ANZAC Alphabet G-M p. 115

The Anzac book / written and illustrated in Gallipolli by the men of Anzac London ; New York ; Toronto ; Melbourne : Cassell, 1916 ANZAC Alphabet G-M p. 115

Corporal Joe Maxwell had to survive a long, hard, heartbreaking day on the 22nd:

Our first attack. We were to face it at dawn, Sunday 22nd August. Why Sunday of all days?

Doherty and I were detailed as stretcher-bearers. We had no shoulder straps to help us with the stretchers. After the first nightmare trips to the dressing station behind the ridge, the job became a back breaking one.

Doherty’s courage, irreverence and ‘queer brand of mordant wit’ helped get them through.

He[Doherty] thirsted for “fags.” As he plucked a packet of Egyptian cigarettes from one pocket his bitter remark was “It’ll be too hot for a cigarette where he’s gone.”

Later Maxwell and Doherty helped a 6’ tall Sikh who ‘had gone down with a bullet hole bored through his waist…’

..[they] dumped him on a stretcher and began to stagger to the station down a slope and over “rough going.” He revived a little and began to pant “Wine-Wine.” “This here Injun,” said Doherty to Dr Dunlop at the station, “keeps yellin’ for wine, Doc- have you got anything to drink? “You damn fool,” the doctor replied, “he has been trying to tell you to wind a bandage round his wound.”

Doherty’s cultural faux pas didn’t end there. Later in the day

…[he] ran against a kindly old padre, Chaplain Waldron, who had been ministering to the dying since “the stunt” began. “I think this Injun is just about to kick the bucket,” drawled Doherty, “he’s been shot clean through the guts, so you’d better tell him a bit about God.” “In spite of your blasphemy,” the padre replied “you have a generous heart. It’s a noble act to show humane conduct to our enemy even though he is a Turk.” “What!” Doherty exploded. “A -----Turk? Well I’ll be damned.” He promptly tipped the wounded Turk off the Stretcher..

Brushed by death’s wings

That night Joe found himself alone with his thoughts.

There under the stars I could not sleep. All kinds of the most melancholy reflections flooded my mind. Thoughts of those huddled bodies in the gully, rigid corpses of boys who had laughed and joked the previous night; thoughts of their folks at home, of the anxiety, the hopes and the fears; thoughts of the melancholy mission of clergymen who would have to break the news, to complete the anguish and despair. So this is war!

So here in the dismal forbidding gully, brushed by the wings of death, lay glory! It was not the heroic theatrical war of the history books. Those black bundles out there, dim and shadowy under the pale starlight, had not even struck a blow at their enemies. In fact they had not seen a Turk. Yet they were cut down, scattered through the ravine, under those friendly stars and by an invisible enemy that had sprayed death from an indefinite vague ridge, a mere blur of green and russet brown in the direction of Suvla Bay.

To me it seemed murder, nothing short of cold blooded murder. I felt sick with the horror of it all. But it was my first night of war.18

‘The Morning After’ by Leslie Hore, 30.6.1915 NSW Library PXE 702 13

‘The Morning After’ by Leslie Hore, 30.6.1915 NSW Library PXE 702 13

Out in no-mans land amongst the huddled, rigid bodies (or remains thereof) were Charles Barker; George Harman Burke, 18, a ‘Town traveler’ and economics student at Sydney Uni.; Clive Sedgwick Cooper, 22, Pastoral student; Joseph Kenneth Donaldson, 28, a newly married Consulting engineer; Mure Robinson Farquar, 34, Grazier; Felix David Saclier, 19, Clerk and Thomas William Watson, 35, Cutter at Anthony Hordern & Sons. All from Mosman.

Also in the dark gullies, amongst the dead was Corporal Rex Boyden. It was a miracle he had survived, shot and pinned down all day by enemy fire:

It was simply wonderful how God watched over me.. shell and shrapnel were bursting within a few yards of me and bullets flying everywhere. I couldn’t possibly move at the time, and it was fortunate I didn’t, for I was behind a dead man and he was sheltering me from the deadly fire of the Turks. I could hear the bullets pelting him while I was lying there…

I thought it would be dark enough for the stretcher bearers to come for me. But it was not to be, for it was bright moonlight, and none came to fetch me, so I lay there until the moon went down, about an hour before daybreak next morning. I managed to crawl about 25 yards, which took me nearly an hour, and brought me near part of our trench. I couldn’t go any further but shouted out for a stretcher bearer, and one of the New Zealanders pulled me out out of the parapet into the trench.19

Hill 60 showing bones of members of the 4th Australian Infantry Brigade and New Zealanders near the position of the old oak tree just beside Turkish trenches. Captain C E W Bean, 1919. [AWM G02079]

Hill 60 showing bones of members of the 4th Australian Infantry Brigade and New Zealanders near the position of the old oak tree just beside Turkish trenches. Captain C E W Bean, 1919. [AWM G02079]

Lessons unlearnt

Charles Bean said of the 18th’s charge on the 22nd

The attempt to round off the capture of Hill 60 by setting a raw battalion, without reconnaissance, to rush the main part of a position on which the experienced troops of Anzac had only succeeded in obtaining a sIight foothold, ended in failure….the attack upon such a position required minute preparation, and that the unskilfulness of raw troops, however brave, was likely to involve them in heavy losses for the sake of results too small to justify the expense.

Within a few hours the 18th Battalion, which appears to have marched out 750 strong, had lost 11 officers and 372 men, of whom half had been killed.20

The Turks now fully awake to British plans, sent extra troops to reinforce the defenses of Hill 60. It was a pity British High Command could not heed their own advice. Kitchener’s message received by Hamilton on July 11th read:

When the surprise ceases to be operative, in so far that the advance is checked and the enemy begin to collect from all sides to oppose the attackers, then perseverance becomes merely a useless waste of life.21

But, in the words of historian Peter Hart:

These were pointless attacks and if they typified any British trait it was a lunatic persistence in the face of the obvious.22

And that lunatic persistence had yet to run its course. The 13th, 14th and 18th Battalion’s survivors joined into 4th Brigade. For another attempt on Hill 60, on August 27th.23

Sunset at Gallipoli, 1915 by Leslie Hore (1870-1935)

Sunset at Gallipoli, 1915 by Leslie Hore (1870-1935)

Their name liveth

Echoing the words of Maxwell, the attack on Hill 60 was, ‘nothing short of cold-blooded murder.’

The following men (already mentioned), lost their lives in this tragic and pointless battle, which typified the waste of the Gallipoli campaign – a small sideshow compared to the main war of attrition in Europe.

Charles Barker, 30; KIA 22/8/1915; 18th Btn.; Costing clerk. Orlando Avenue. Barker’s mate said that: “Barker was shot in many places and had told him not to bother about him as he knew he was dying.”

George Harman Burke, 18; KIA 22/8/1915; 18th Btn.; Traveller, economics student, University of Sydney. Played fullback for Mosman Rugby Club. Brother of Thomas Burke AN&MEF and of James Burke, 2/10th Field Ambulance, 8th Div. 2/AIF lost when Rakuyo Maru torpedoed when carrying Australian POW’s to Japan on 12/09/1944.

Clive Sedgwick Cooper, 22; KIA 22/8/1915; 18th Btn.; Pastoral student. 33 Spencer Rd.

Joseph Kenneth Donaldson, 28; KIA 22/8/1915; 18th Btn.; Consulting engineer. Wife Doris, “Doondi” Almora St.

Mure Robinson Farquar, 34; KIA 22 /8/1915; 18th Btn.; Grazier. Mother Margaret, 8 Boyle St. Sister, Anne – Australian Army Nursing Service and brothers Francis – 9 Mobile Veterinary Service; James – 5 Brigade Ammunition Column; and Noel – 5 Field Artillery Brigade.

Felix David Saclier, 19; KIA 22/8/1915; 18th Btn.; Clerk, Parents Louis & Fannie, 11 Silex Rd, Mosman. “… he was a brave little fellow, quite young.”

Thomas William Watson, 35; KIA 22/8/1915; 18th Btn.; Cutter, Anthony Hordern and Sons. Served Boer War AN&MEF. Father Sydney, 57 Glover St, Mosman.

Source: Franki, George Their name liveth for evermore : Mosman’s dead in the Great War 1914-1918. [Waverton, N.S.W.] George Franki, 2014.

Articles about the August offensives at Gallipoli.

Hill 60 and the lost 18th. Aug. 22, 1915

Hill 60 and the lost 18th. Aug. 27, 1915

Remembering Major T.H. Redford, at The Nek

Footnotes

1 Maxwell, J. (Joseph), Murphy, G. F., (George Francis), 1883-1962 and Martin, Steve Hell’s bells & mademoiselles ([Rev. ed.]). HarperCollins Publishers, Sydney, 2012. p9

2 Maxwell, J. Murphy, G. F., p8

3 Regiments and battalions from the 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th, 9th, 12th and 11th Cav. Reg

Extra artillery included Field Snieder Battery; 15cm Howitzer; 12cm gun; 3 × 8.8 cm gun; 1 naval gun; 2 × 12cm Howitzers. Broadbent, Harvey Gallipoli : the Turkish defence : the story from the Turkish documents. Carlton, Victoria The Miegunyah Press, 2015 p. 344

4 Hart, Peter Gallipoli. Oxford New York Oxford University Press, 2011. p. 380

5 Maxwell, J. Murphy, G. F., p12

6 Bean, C. E. W. (Charles Edwin Woodrow), 1879-1968. Official history of Australia in the war of 1914-1918. Angus and Robertson, Sydney, N.S.W, 1921. Ch. 26 Hill 60 www.awm.gov.au/images/collection/pdf/RCDIG1069534—1-.pdf p748-762 retrieved online 10/08/2017

7 Ibid Bean, C. E. W. Official history of Australia in the war of 1914-1918 p748-762

8 Hart, Peter Gallipoli. Oxford New York Oxford University Press, 2011. p. 381

9 Ibid Maxwell, J. Murphy, G. F., p11

15 Maxwell, J. Murphy, G. F., p13

10 Ibid Bean, C. E. W. Official history of Australia in the war of 1914-1918 p748-762

11 Ibid

12 Ibid

13 Ibid

14 Hart, Peter Gallipoli. Oxford New York Oxford University Press, 2011. p. 381

16 Bean, C. E. W Official history of Australia in the war of 1914-1918.

17 Ibid

18 Maxwell, J. p16

19 Hart, Peter Gallipoli. p. 382

20 Bean, C. E. W Official history of Australia in the war of 1914-1918.

21 Ibid.

22 Hart, Peter Gallipoli.

23 As on the 21st they joined the NZ Mounted Rifles, 9th and 10th Australian Light Horse, Connaught Rangers, Ghurka Riflemen, Welsh Borderers and New Hampshires to take - and hold - Hill 60. The battle lasted into the night as both sides struggled desperately - and paid dearly - for each metre of trench