Sydney’s 2-F1 Sopwith Camel (N6822) launching from platform. This photograph is probably of an aircraft that replaced Lt. Sharwood’s (N6783)

Sydney’s 2-F1 Sopwith Camel (N6822) launching from platform. This photograph is probably of an aircraft that replaced Lt. Sharwood’s (N6783)

After leaving SMS Emden ‘wrecked and done for’ in 1914, HMAS Sydney served with the British North Sea fleet.

HMAS Sydney was involved in some interesting engagements.

Under her innovative commander, Captain Dumaresq, Sydney fought a running duel with German submarines and a Zeppelin on May 4th, 1917.

In August 1917 Sydney had an overhaul. She was fitted out with the latest equipment, including a revolving aircraft launching platform (the first to be installed on an Australian warship), and a new tripod mast, now a permanent memorial at Bradley’s Head.

First mast being replaced during her re-fit in the UK

First mast being replaced during her re-fit in the UK

Floating crane ‘Titan’ installing the mast at Bradley’s Head after the war

Floating crane ‘Titan’ installing the mast at Bradley’s Head after the war

In December 1917, Dumaresq loaned a Sopwith ‘Pup’ fighter from HMAS Dublin. On Dec.8 the ‘Pup’ was successfully launched with the ship turned into the wind – an Australian naval first. On Dec.17, a second launch was made. This time with the movable platform turned into the wind – a world naval first.

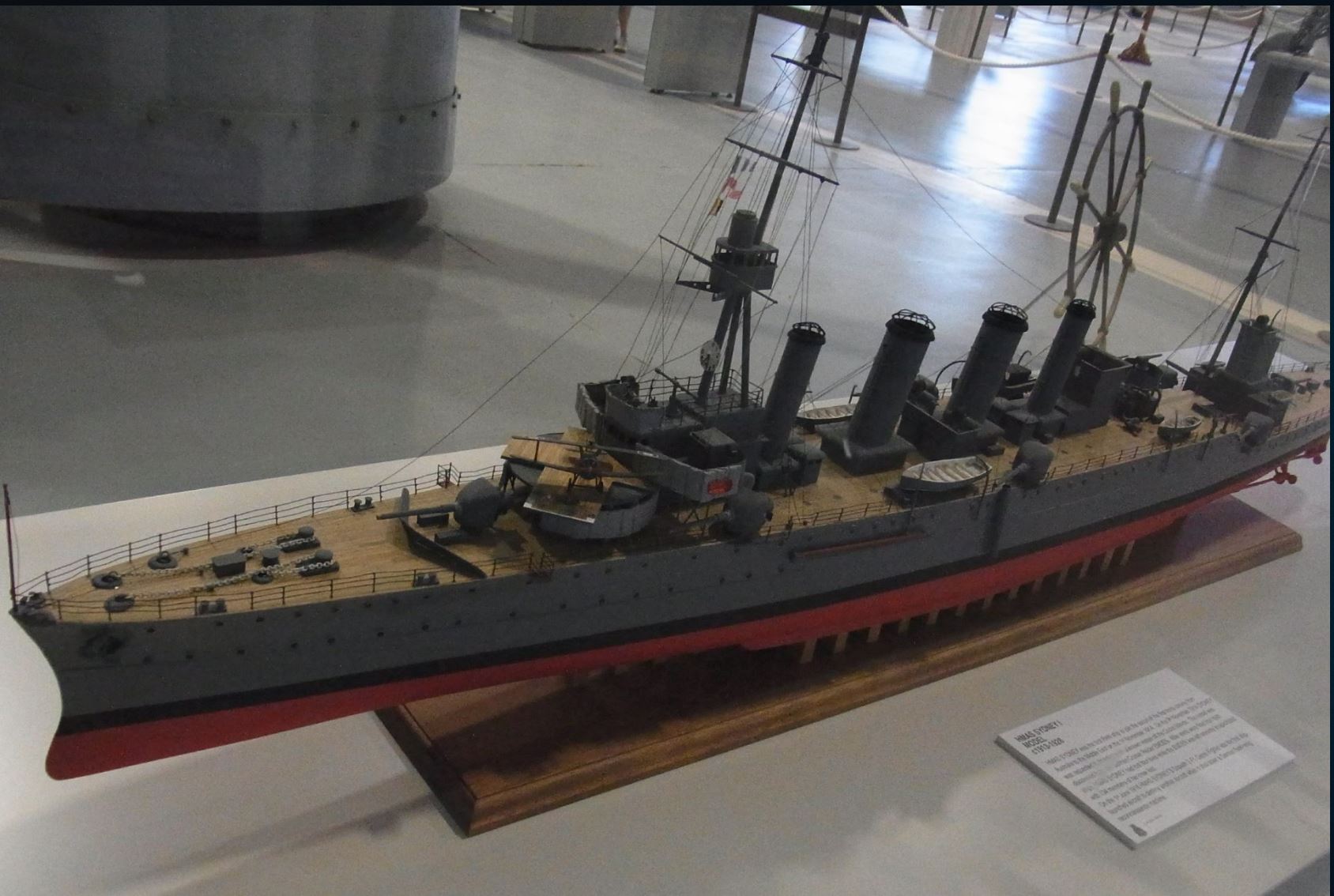

Model Of HMAS Sydney (I) at Fleet Air Arm Museum, Nowra. Full view of ship and close-up showing Sopwith fighter on launching platform. Photo taken by the Author

Model Of HMAS Sydney (I) at Fleet Air Arm Museum, Nowra. Full view of ship and close-up showing Sopwith fighter on launching platform. Photo taken by the Author

Within six months Dumaresq’s advocacy of ship-launched aircraft would be vindicated. In early 1918, Sydney replaced her Sopwith Pup with a modified Sopwith Camel – a 2-F1 ‘Ships Camel’.

On 1 June 1918, 2 German seaplanes1 were sighted by Sydney diving towards HMAS Melbourne. Both aircraft dropped bombs but no hits were scored.

Within minutes Lieut. A.C. Sharwood from Sydney, and Flight Lieut. L.B. Gibson from Melbourne were strapped into their Sopwith fighters and launched into the wind.

Sopwith F.1 Camel takes off from HMAS Sydney. HMAS Melbourne is in the background.

Sopwith F.1 Camel takes off from HMAS Sydney. HMAS Melbourne is in the background.

Sharwood and Gibson climbed rapidly to intercept the enemy. Gibson lost sight of his quarry in the clouds. Sharwood continued the pursuit:

Lieutenant Sharwood, followed his enemy persistently for 60 miles, in the end attaining a position “on its tail,” and giving it several salvoes from his machine gun. As it dropped in a spinning nose-dive through the mist, and Sharwood prepared to follow it and make quite certain that it had “crashed,” he found another German machine just behind him and was compelled to rise again and fight; soon afterwards one of his guns ran out of ammunition and the other jammed, and he thought it wiser to make back towards home.

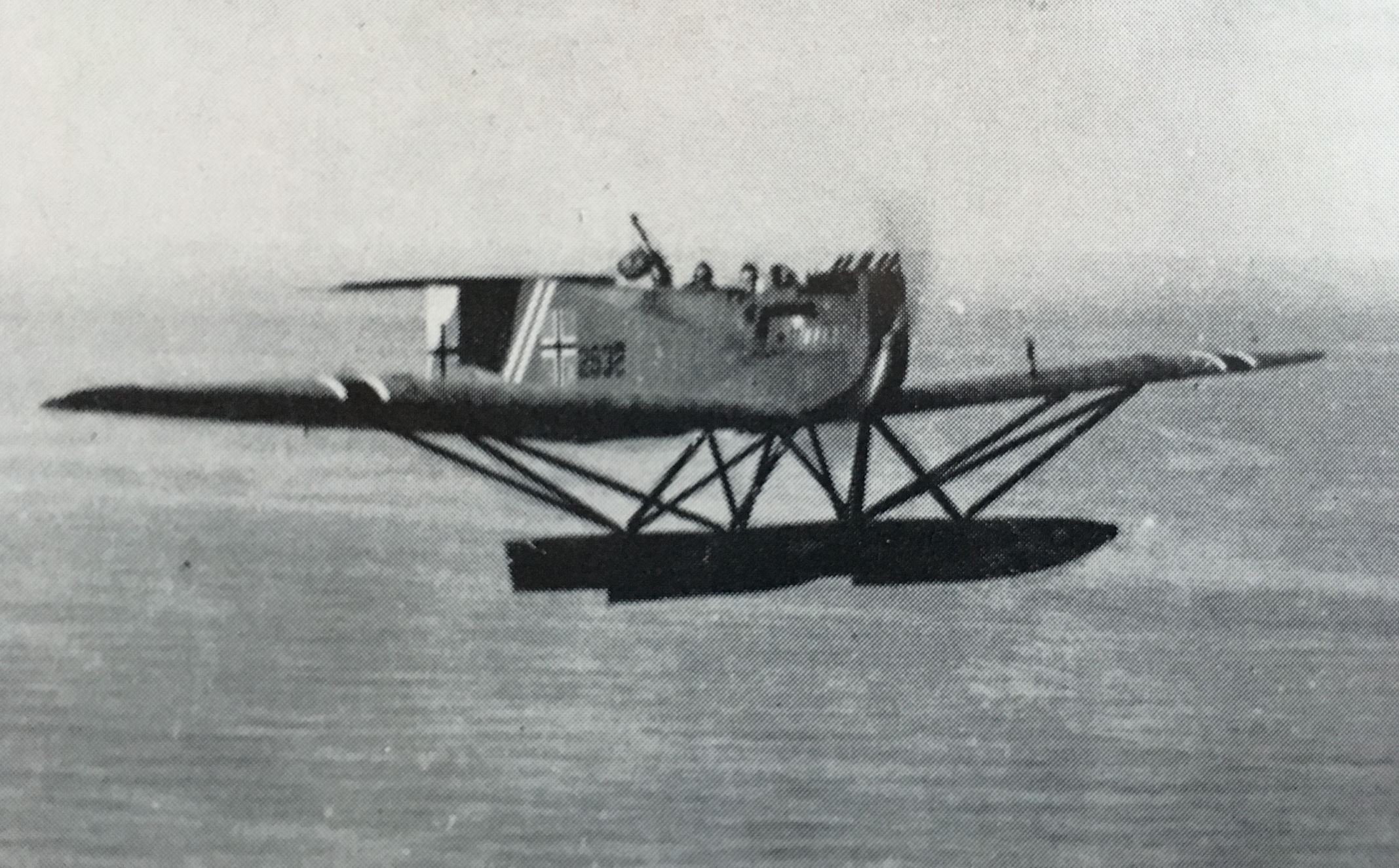

Above Hansa Brandenberg and Friedrichshafen 2-seat aircraft. Either type or a variant could have attacked on the day.

Above Hansa Brandenberg and Friedrichshafen 2-seat aircraft. Either type or a variant could have attacked on the day.

Out of options, he broke from the fight. After losing his attacker in cloud cover, Sharwood tried to find the HMAS Sydney . But Sydney was now over 70 miles away!

After a long and unsuccessful search which used up his supply of petrol, he sighted two light cruisers and several destroyers, one of which fired at him; observing that they were British, he flew down and took the water ahead of a destroyer, which proved to be the [HMAS] Sharpshooter. The actual landing (if one may use that word in the absence of land) was bound to be difficult, as this type of machine usually turned a somersault when it hit the water, and threw its pilot out. Sharwood was a little more lucky. His machine merely stuck its nose deep into the sea and remained there, tail in the air, while the contained air slowly bubbled out of it – and Sharwood hung onto the tail for twenty minutes, the destroyer eventually sending a boat for him. The Canterbury picked up his machine.

Adventures with aircraft : HMAS SYDNEY [I]‘s Sopwith Pup lands in the North Sea – ‘Warship’ magazine.’ Source: Horatio J. Kookaburra’. ‘

Adventures with aircraft : HMAS SYDNEY [I]‘s Sopwith Pup lands in the North Sea – ‘Warship’ magazine.’ Source: Horatio J. Kookaburra’. ‘

Lt. Sharwood’s actions proved the value of aircraft in preventing enemy air attacks and intelligence gathering at sea. The ship-launched air battle was yet another world first for HMAS Sydney5

Archive footage!

[Imperial War Museum]: IWM 638

Object description:

Instructional film showing how an RAF Sopwith Camel can be launched from the light cruiser HMS Sydney, fly to land at Rosyth seaplane base, and re-join the ship on her return, September 1918.

Full description:

The Camel is mounted on a launch platform above the light cruiser’s ‘A’ Turret. The crew makes ready for launch, removing the safety netting and holding wires. The plane’s engine is turned over (very good view of the rotary engine), it builds up speed and launches directly over the turret, which is swung out to starboard. The Camel lands conventionally at an aerodrome not far from Rosyth after flying its mission. A Royal Navy groundcrew performs a quick check on the machine, then wheels it by a ramp onto a lorry. The Camel is then unbolted immediately behind the cockpit, and the two halves re-arranged one under the other on the lorry for easier transportation. The lorry arrives at the seaplane base where the aircraft is reassembled and checked over. It fails to satisfy the mechanics on a second check and another Camel is provided as a substitute. This is put on a lorry (which has a long tailboard specially designed to take the aircraft in one piece) and driven to South Arm, Rosyth. Here a crane transfers the plane to the lighter Guide Me which takes it out to the Sydney or a similar Chatham Class light cruiser. The ship’s derrick takes the Camel on board and it is fitted back onto its launch platform.

Footnotes

1 At this stage it is unknown what types these were but the single-seaters may have been Albatros or Rumpler types; and 2 seaters, Hansa-Brandenbergs or Friedrichshafen.

2 Full account: AWM First World War Official Histories – Volume IX – The Royal Australian Navy, 1914–1918 9th ed., 1941. p 305 306. retrieved online 21/01/18 https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1416827 The German shot down was a single seater the other a 2 seater. Sharwood was not credited with a victory by the Admiralty.

3 Fleet Air Arm Association of Australia Our Heritage: RAN Naval Aviation 1913-1947 retrieved online 6/11/2018. Another source says both guns jammed (both the Vickers and Lewis guns.) It is unknown which gun jammed (presumably the Vickers?)

4 Although the image above identifies HMAS Sharpshooter with the Camel strapped to her bow, HMAS Canterbury salvaged the ship. Source: Fleet Air Arm Association of Australia Our Heritage: RAN Naval Aviation 1913-1947 retrieved online 6/11/2018 https://www.faaaa.asn.au/ran-naval-aviation-1913-1947/

5 Flt Sub Lt Smart, RNAS, flying a Sopwith Pup from HMS Yarmouth on 21/08/17 had previously shot down Zeppelin L23

This article is an excerpt from: After Cocos: HMAS Sydney’s progress

Follow the Sydney-Emden story

After Cocos: Sydney-Emden memorial unveiled!

After Cocos: HMAS Sydney’s progress

After Cocos: Holsworthy Concentration Camp

Sydney v Emden, a century later

HMAS Sydney’s mast dedication, 80 years ago today

Sydney’s mast not destined for ‘Sow and Pigs’

h.4 Appendix: C.E.W. Bean’s account

From: First World War Official Histories – Volume IX – The Royal Australian Navy, 1914–1918 Chapter X – ‘Service in European Waters’, 1st June, 1918

The Sydney was now back with the squadron, having rejoined it at Scapa on the 1st of December. The early records of 1918 are concerned with escort work, sometimes in company with a squadron of battle-cruisers, or occasionally with battleships, including those from the United States Navy which formed part of the Grand Fleet.43 The conditions may be guessed from a report which states that, during escorting operations from the 6th to the 9th of January, “the bores of the guns in all ships were choked with ice and were out of action… until arrival in harbour.” Meanwhile, Dumaresq had attained his heart’s desire, launching-platforms for aeroplanes having been fitted in the two Australian cruisers; the first flight off the Sydney’s platform was made successfully on the 8th of December, 1917. Among other incidents of this period the diary already quoted notes several attempts of the Grand Fleet to lure the Germans into the open. “We were off Heligoland,” notes an entry for the 1st of February.

letting rip with a 6-inch gun to let Fritz know we were there. The Grand Fleet was only about 12 miles off. Fritz was not having any.

On the 11th of April “Grand Fleet went out to sea on a spasm ”; and on the 29th the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron helped the 1st Battle Squadron— Revenge, Resolution, Royal Oak, Royal Sovereign, Ramillies, and Canada, a trumpet-call of great names – to escort to Norway a convoy of ninety-two vessels. The achievements of the German High Sea Fleet may have been few, but the work of their lighter vessels must be respected, seeing that it evoked so overwhelming a defence. Both the Melbourne and the Sydney had by now aeroplanes of their own. The Sydney’s launching-platform had been fitted up while she was at Chatham, and was inspected at Rosyth on her way back to Scapa (30th of November) “with a view to framing proposals for flying arrangements in other light cruisers.” The Melbourne took aboard her flying officer, Flight-Lieutenant Gibson (Flight-Lieut. L B. Gibson, R.A F. Civil Servant, of Coventry, Eng: b. 14 April, 1896.) on the 14th of April, but does not seem to have experimented with the aeroplane till the 10th of May In June occurred an unexpected test of the Australian cruisers’ aeroplane organisation. The now-famous Harwich Force (nine light cruisers and twenty-eight flotilla leaders and destroyers) was at the time mainly occupied with reconnaissance work and the destruction of enemy mine-sweepers in and near the Heligoland Bight; consequently these mine-sweepers were being supported by German destroyers and light cruisers, with battleships – sometimes a division of them-within reach and the whole area was patrolled by aeroplanes and Zeppelins. To test the strength of this support, and if possible to break it down or bring on a general engagement, Admiral Beatty planned a raid in force into the bight. The Harwich Force went off in advance and was followed on the 1st of June by three detachments working along separate routes. The main body, with which alone this narrative is concerned, consisted of:

(a). the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron with four attendant destroyers; and

(b). some miles behind, the aeroplane-carriers Courageous and Glorious with their destroyers; with H.M.S. Champion and nine destroyers.

©. the First Battle Cruiser Squadron, led by the Lion, Thus if, to protect their smaller craft against the light cruisers, the enemy’s battleships were tempted out of hiding, a superior British force could be launched against them unexpectedly- provided the German air-scouts did not first take back news of the big ships in the offing.

Late in the afternoon there suddenly appeared out of a sky covered with large broken clouds two enemy aeroplanes flying direct for the British fleet; they were not visible till almost overhead, passed the light cruisers, sighted the battlecruisers, dropped five bombs in their neighbourhood, and at once made off eastwards to report what they had seen. The whole process, from their first appearance to their return over the light cruisers, took perhaps five minutes. But for such an emergency Dumaresq had long since prepared; the_Sydney_’s pilot was continuously on duty close to his aeroplane, a bugle-call summoned the despatching crew, and the machine could be away within two minutes of giving the alarm (the Melbourne, of course, had similar arrangements). So, when the German aeroplanes returned, the machines from both Australian cruisers were in the air, climbing rapidly to intercept them.

Unfortunately, Flight-Lieutenant Gibson of the Melbourne lost sight of his opponent very soon through cloud- interference, and, observing Gibson’s return, the Courageous, which had not yet launched an aeroplane, refrained from sending one up at all. But the Sydney’s pilot, Flight- Lieutenant Sharwood, (Capt. A C. Sharwood R A.F.; of Bournemouth, Eng.; b. 7 March. 1899) followed his enemy persistently for sixty miles, in the end attaining a position “on its tail,” and giving it several salvoes from his machine-gun. As it dropped in a spinning nose-dive through the mist, and Sharwood prepared to follow it and make quite certain that it had “crashed,” he found another German machine just behind him and was compelled to rise again to fight; soon afterwards one of his guns ran out of ammunition and the other jammed, and he thought it wiser to make back towards home. After a long and unsuccessful search which used up his supply of petrol, he sighted two light cruisers and several destroyers, one of which fired at him; observing that they were British, he flew down and took the water ahead of a destroyer, which proved to be the Sharpshooter. The actual “landing” (if one may use that word in the absence of land) was bound to be difficult, as his type of machine usually turned a somersault when it struck the water, and threw its pilot out. Sharwood was a little more lucky. His machine merely stuck its nose deep into the sea and remained there, tail in air, while the contained air slowly bubbled out of it-and Sharwood hung on to the tail for twenty minutes, the destroyer eventually sending a boat for him. The Canterbury picked up his machine.

The achievement of the Sydney’s aeroplane went practically unrecognised, the officer in command of the light cruiser squadrons having apparently taken it for granted that Sharwood had shared Gibson’s bad luck. Further, Sharwood did not even get credit for having shot down an enemy machine, since he could not state that he had actually seen it fall into the water. But the operation – whether the German aeroplane was destroyed or not – was entirely successful. ‘The German scouts were after bigger news than the presence of light cruisers or even battle-cruisers; they wanted to know whether the Grand Fleet was out-and in a few minutes more they would have known. Before, however, they had seen more than the Lion and her comrades (not an uncommon sight in those waters), the ’planes from the Australian ships were rising to intercept them, and they were forced to return in a hurry. On the other hand, had they neglected these two ’planes and gone on to find out what they were looking for, Sharwood and Gibson would have caught and probably destroyed them, or at any rate, detained them so long that the Courageous could have sent hers to complete the work.