Holsworthy Internment Camp, c.1915. Photograph Heinrich Jacobsen, Dubotzki Collection, Germany. Source: NSW Migration Centre ‘The enemy at home.’

Holsworthy Internment Camp, c.1915. Photograph Heinrich Jacobsen, Dubotzki Collection, Germany. Source: NSW Migration Centre ‘The enemy at home.’

Woe to the vanquished

For Emden’s survivors, their story did not end after the battle with HMAS Sydney

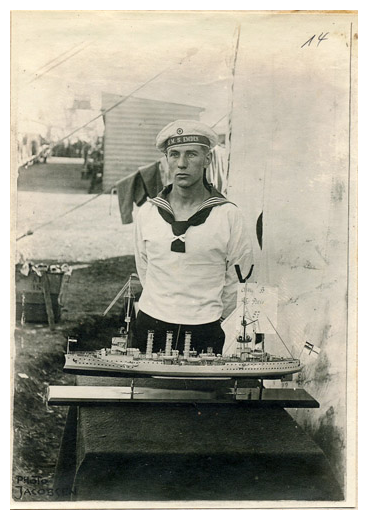

Internee’s scale model of the SMS Emden, Holsworthy Internment Camp, c.1915. Photograph Heinrich Jacobsen, Dubotzki Collection, Germany. Source: NSW Migration Centre ‘The enemy at home.

Internee’s scale model of the SMS Emden, Holsworthy Internment Camp, c.1915. Photograph Heinrich Jacobsen, Dubotzki Collection, Germany. Source: NSW Migration Centre ‘The enemy at home.

Some of Emden’s crew and their Captain Karl Von Müller made a daring escape across the globe1, and became decorated heros. Others were captured. They had survived the horrors of Emden’s twisted, burning wreck, to languish as prisoners in Australia. Sharing their internment with other German enemy aliens in concentration camps for the war’s duration.

Of all the camps Holsworthy was the harshest and resembled a prison in the true sense of the word. A strict regime of control was enforced by the camp authorities. Raids often turned up stills and grog making faculties.2

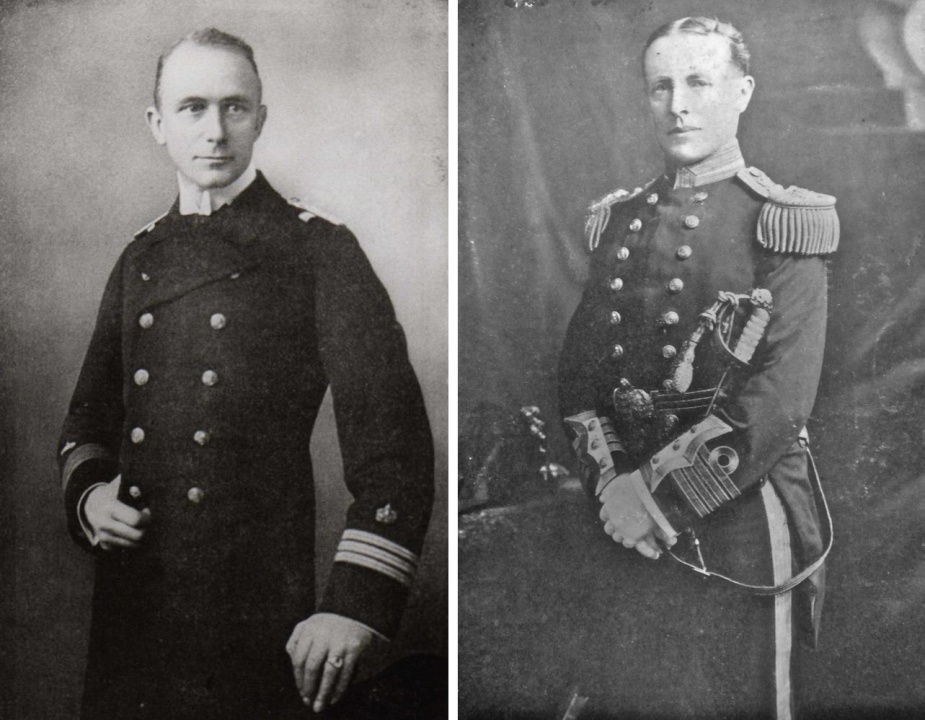

Illicit still for making alcohol made by the internees at Holsworthy c.1916. Dubotzki collection, Germany

Illicit still for making alcohol made by the internees at Holsworthy c.1916. Dubotzki collection, Germany

Internees were seldom allowed out of the camp confines and here boredom and melancholy took hold….The internees were not allowed to free range like those at Berrima or Trial Bay and were kept behind barb wire fences and watched over by guards with a mounted machine gun in a substantial watchtower on the southern perimeter.3

Colonel Sands and the Black Hand

Colonel Sands was appointed to the role of ‘Commandant of the concentration camps of Australasia’ including Trial Bay, Berrima and Holsworthy. His connection with Mosman was that he later lived in Silex Rd, Mosman.

Portrait of Colonel Robert Sands (centre) and two permanent German officers captured in New Guinea, Captain von Klevitz and Lieutenant Meyer. (original album held in AWM archive store).

Portrait of Colonel Robert Sands (centre) and two permanent German officers captured in New Guinea, Captain von Klevitz and Lieutenant Meyer. (original album held in AWM archive store).

In early 1915 there were riots over rations and work duties that were subdued by negotiations between the camp commandant Colonel Sands and the Camp Committee. In order to keep the camp under control Sands ran the camp firmly. Troublesome internees were singled out and thrown into solitary confinement in the camp gaol. There were regular searches for contraband and weapons.4

The Black Hand gang held some sway over internees and control of the Camp’s Committee

On April 18, 1916 matters came to a head. Inmates rebelled against the gang’s stand-over tactics. Colonel Sands found himself in the midst of an ugly riot.

Ringleaders were beaten up and thrown over the compound’s main gate:

A crowd gathered at the gate yelling in English ‘these two men of the Black Hand Society have got what they deserved and there are more to come’. Colonel Sands and a group of police went into the crowd who were armed with home made batons and clubs, but no attempt was made to injure the police.5

Colonel Sands could have ordered his men to fire on the crowd, but allowed the vigilante action to continue:

Shortly after there was a ‘rush of Germans all over the compound’ who were looking for the other four main members of the Back Hand gang.6

The incensed crowd found the four other men and gave them the same treatment. Camp guards took the lynched thugs to the camp hospital. Later fourteen other Black Hand members were arrested and thrown into the camp jail. Two died in the melee:

and after that the Camp quietened down to the usual routine.7

The bodies of two internees who were killed during a riot on the 18th April 1916.Dubotzki collection.

The bodies of two internees who were killed during a riot on the 18th April 1916.Dubotzki collection.

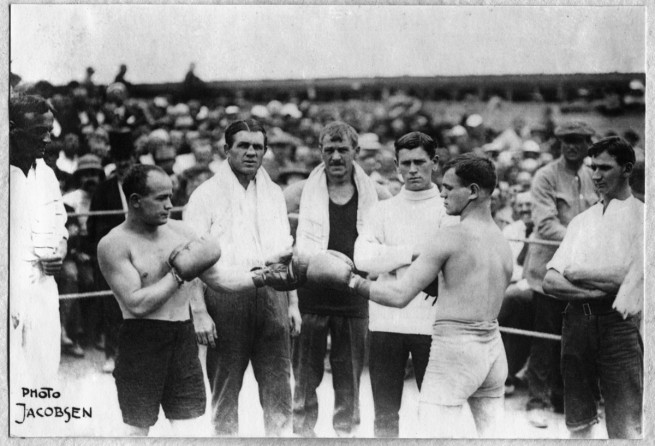

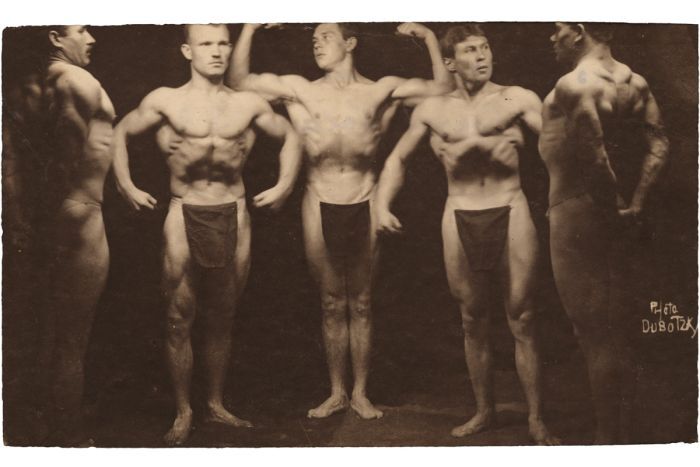

Photographs of leisure and industry

The internees alleviated the atmosphere of confinement, deprivation of liberty and constant surveillance with literary, cultural and sporting activities. Physical outlets such as boxing, weightlifting and gymnastics alleviated boredom and melancholy.8 Cultural activities such as crafts (making wooden furniture, toys and models) and the performing arts (music and theatre) also constructively passed the time.

Boxer Frank Bungardy, third from left, who established a boxing and self-defence school at Holsworthy. Picture: Paul Dubotzki Collection

Boxer Frank Bungardy, third from left, who established a boxing and self-defence school at Holsworthy. Picture: Paul Dubotzki Collection

Hans Overbeck (centre) in a theatre production put on by prisoners in Holsworthy camp. Source: retrieved online at https://jonolineen.com/2014/07/27/on-the-inside/

Hans Overbeck (centre) in a theatre production put on by prisoners in Holsworthy camp. Source: retrieved online at https://jonolineen.com/2014/07/27/on-the-inside/

The German Concentration Camp at Holsworthy, near Liverpool, New South Wales, showing internee life during World War I File number: FL3371613 File title: 82. Internee life GCC Orchestra 1916

The German Concentration Camp at Holsworthy, near Liverpool, New South Wales, showing internee life during World War I File number: FL3371613 File title: 82. Internee life GCC Orchestra 1916

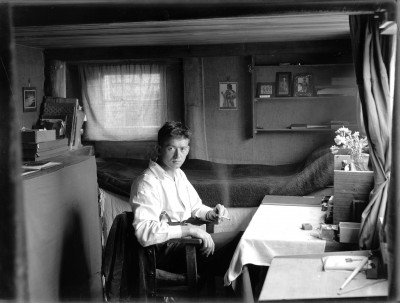

Life at the internment camps was captured by photographer Paul Dubotzki.

Paul Dubotzki: Photographer, Trial Bay c. 1916. Dubotzki collection, Germany

Paul Dubotzki: Photographer, Trial Bay c. 1916. Dubotzki collection, Germany

His photographic collection (discovered after his death) is a wonderful visual documentation of this otherwise forgettable part of Australian History. The digitised images are viewable at the NSW Migration Centre ‘The enemy at home’ site. A sample of his collection is provided below:

Internees at Enoggera Internment Camp, c.1915. Dubotzki collection, Germany

Internees at Enoggera Internment Camp, c.1915. Dubotzki collection, Germany

Athletic club on Torrens Island (Paul Dubotzki/ National Library of Australia)

Athletic club on Torrens Island (Paul Dubotzki/ National Library of Australia)

Communal latrines, Holsworthy Internment Camp, c.1915. Dubotzki collection, Germany

Communal latrines, Holsworthy Internment Camp, c.1915. Dubotzki collection, Germany

The the War Memorial and State Library of NSW also have interesting digitised photographic collections, This includes includes images of Emden’s crew (in and out of uniform) standing behind their scatch-built scale model Emden ships.

The German Concentration Camp at Holsworthy, near Liverpool, New South Wales, showing internee life during World War I. File number: FL3371544 File title: 34. GCC Holdsworthy internees with ‘Emden’ models.

The German Concentration Camp at Holsworthy, near Liverpool, New South Wales, showing internee life during World War I. File number: FL3371544 File title: 34. GCC Holdsworthy internees with ‘Emden’ models.

The German Concentration Camp at Holsworthy, near Liverpool, New South Wales, showing internee life during World War I. File number: FL3371692 File title:161. GCC Holdsworthy – more model builders

The German Concentration Camp at Holsworthy, near Liverpool, New South Wales, showing internee life during World War I. File number: FL3371692 File title:161. GCC Holdsworthy – more model builders

Appendix: Eyewitness accounts to Emden’s destruction

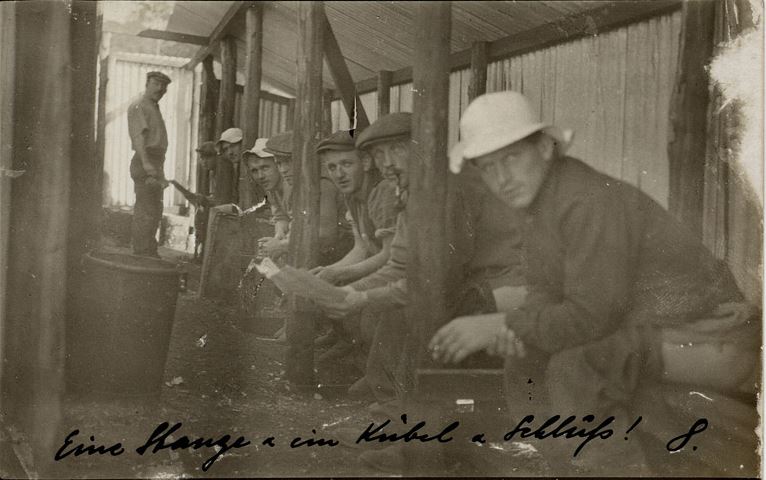

Photo graph of 1) HMAS Sydney and 2) SMS Emden (at Tsingtao in 1914.)

Photo graph of 1) HMAS Sydney and 2) SMS Emden (at Tsingtao in 1914.)

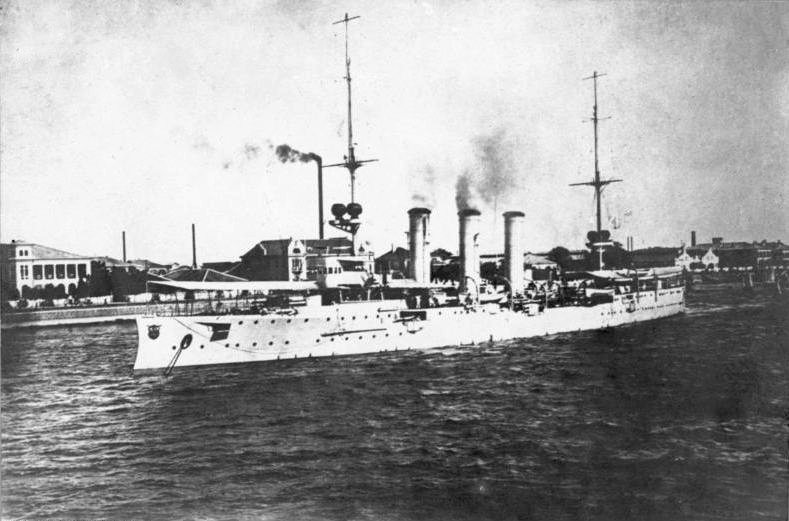

Fregattenkapitän (Frigate Capt.) Karl von Müller, of the Emden; and Capt. J.C.T. Glossop of the Sydney.

Fregattenkapitän (Frigate Capt.) Karl von Müller, of the Emden; and Capt. J.C.T. Glossop of the Sydney.

A German Survivor’s Account

Described as an unassuming, middle-aged man, Mr Hans Heinz Harmes-Emden, of Shanghai, reviewed, at the request of the North China Daily News his experiences as an engine room petty officer of the famous German cruiser.

“Hell on the Emden”

“HELL on the EMDEN” The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1950) 10 November 1936: 5 (FINAL EXTRA). Web. 27 Oct 2017 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article85171194

Rear-Admiral Robert Witthoeft, of the German Navy, as told to Wayne Francis Palmer, in the American magazine ‘Liberty.’

It happened yesterday…years ago…

THE German cruiser Emden was the terror of the Pacific and Indian Oceans during theearly months of the World War.

Operating alone and without a base, and with half the world against her, she harried Allied shipping in one of the most daring sea raids of all time. Starting from China, where she was stationed when war was declared -in August, 1914, the Emden blocked the transportation of Anzac troops to France, shelled British oil reserves at Madras, and sank some ‘ £3,000,000 worth of shipping, after first removing non-combatant crews. In one typical raid she crept at dawn into the harbor of Penang and blew up a Russian cruiser with a sudden hail of shells that gave the doomed crew not even a chance to fight.

But on November 9, 1914, she was surprised in turn. While putting a landing party ashore to destroy the British cable station at Cocos Island, Captain von Muller, of the Emden sighted a hostile cruiser approaching.

One of the Emden’s officers here describes what followed:

‘The bugle blared. There was the tramping of feet as men rushed to their battle stations. Gun breeches banged. Then order and silence reigned as the Emden steamed out to meet the enemy.

‘It looks like the Newcastle,’ said the captain, as he squinted through the slit in the conning tower.

‘That’s not so bad. She may have a little more gun power than we but I’ve got the Emden’s crew! Full speed ahead.’!’

‘We were the first to open fire, at about 10,000 yards, on a course parallel with the mysterious British cruiser. Our third salvo struck her upper works and sent up a cloud of black smoke. First blood!’ Gunnery Officer Gaede yelled. ‘We’ve ‘got their range. Now let them have it.’!!’

‘Meanwhile, there was a flash of orange flame from the other ship as they gave us their broadside. We could actually pick up the shells as they came toward us, looking like so many bluebottle flies.They seemed to waver as they neared, and then we lost them as they moaned over us. Soon, however, great geysers began rising out of the sea so close to us that they brought tons of water crashing down on our deck.’

‘We’re in for trouble,’ Captain von Muller said quietly. ‘Those splashes are from a much heavier ship than I had thought.’

He turned to the navigating officer.

‘Closer, Gropius, closer,’ he ordered and the Emden edged over toward the enemy to reduce the range.’

‘Under the clouds of yellowish smoke that billowed the enemy, I saw our shells striking her time after time; but mean-while her shots were getting uncomfortably near us. Then with a crash the first shell came aboard us and burst in the wireless cabin. Instantly nothing was left but its twisted white-hot steel frame. Our faithful operators, who for so long had been our only link with the outside world, were destroyed.’

‘Immediately thereafter a shell burst with an appalling- noise directly in front of the conning tower. For the next few seconds everything was strangely silent. We missed the rapid bark of the forward gun, but in its place came the groaning of the wounded and dying. It was a frightful mess out there. Gaede called up a reserve crew; and the captain repeated his order: ‘Closer, Gropius, closer!’

‘But already we knew that we did not have a chance. They would run out as we tried to close in, and then with their longer range guns they would pound us unmercifully.’

‘The battle became a nightmare to me. Lieutenant Zimmerman, seeing that there was more trouble with the forecastle gun, dashed forward from the conning tower. Just as he arrived an explosion killed him and every man at the gun. That same shell got the captain and myself, but only slightly. Then forward smokestack was hit and collapsed. The foremast came down and slid off into the sea, carrying with it the foremast crew. Gropius dashed aft to see what was wrong with the rudder.’

‘There was now a slackening in our rate of gunfire, and Gaede left the conning tower to find out why. He hadn’t gone far before a shell splinter got him, and he fell dying to the deck, his white uniform drenched with blood. Our two remaining stacks were hit and took a cock-eyed tilt. Suddenly there was a ghastly concussion somewhere amidships as the deck folded up and buckled. A broadside gun hurtled up into the air. Men, steel plates, mess benches, and great splinters could be seen in the flying mass of debris.’

‘Everything seemed on fire at once. Gropius was caught aft with a few survivors from the poop gun. Intent on what they were doing, they didn’t notice that the flames were eating their way aft until a solid wall of fire confronted them.They tried to break through by, going to a lower deck, but down there it was like some terrible furnace.’

‘Step by step they were forced: to retreat, until they were, huddled together on the very stern. Swiftly the flames rushed at them; they knew the end was at hand. Gropius led three cheers for our Fatherland. But before they had finished a shell hit nearby and they were all blown overboard.’

‘Up in the conning tower, Captain von Muller and I were now alone. Our guns were silent our ammunition exhausted. Our ship was without a rudder. ‘It’s no use going on, Witthoeft,’ the captain said. ‘This is nothing but slaughter. I must save what men I can, and yet I won’t let them have my ship. See, there is North Keeling Island dead ahead. I’m going to try to put her there high and dry.’‘

‘While the British fairly poured their shells into us, we rushed full speed for the beach. We signaled the engine-room force to climb to safety. With a tearing impact the Emden slipped in between two large coral reefs, and there, about 100 yards offshore, our ship came to rest, a burning, sinking charnel house.’

‘Our cruise had ended. Captain von Muller told those of us who had collected around him on the upper deck that we might try to swim ashore if we wished. A few tried, but only five of them reached the beach. The others were crushed on the reef. The captain ordered all survivors up to the comparative safety of the forecastle.’ Half the officers were dead. The deck and gun crews were almost entirely wiped out. The engine-room and fire-room crews now made up most of our little band.’

‘Some us went below to look for the wounded. Of all the experiences of my life, that was the most ghastly and crushing. Here and there a single candle spluttered, but it only added to the horror. The stench of burning hammocks and1 burned human flesh nauseated us. Bodies, or what had been bodies, lay strewn about the guns and in the passageways. The mutilation of the dead was beyond belief. All was silent below decks, except the steady, muff led roar and crackling of the flames.’

‘On the forecastle the condition of the wounded was pitiful. They, cried for water, but the tanks had been shot away. As though our afflictions were not enough, a number of vicious sea birds settled down on the deck. As we lift one helpless wounded man to go to another, they would rush at him and tear at his eyes or at his wounds. We tried to beat them back with clubs. Never having seen any men before, they were without fear of us.’

‘Our situation was becoming unbearable and the shore seemed such a little way to go — only 300 feet. Our boats had been blown to bits or burned. We tried floating light lines attached to boxes to the men who had reached shore, but every, attempt failed.’

‘Meanwhile the enemy-we later learned it was the Australian cruiser Sydney — had steamed away to capture our landing party on Direction Island. We settled down to a night of hell, surrounded by, our wounded shipmates, for whom we could do nothing, all of us threatened with a fiery death from the still raging flames.’

‘At dawn we started our second day of torture. Many of the wounded were delirious. It was agreed if the Sydney didn’t return we would all be lost. In the afternoon, however, the Sydney was sighted. Good. Our wounded would have their chance.’

‘We thought the British were going to rescue us. But suddenly salvo after salvo came from the cruiser. Shells ploughed into the stricken Emden and exploded. Fires again sprang up everywhere. I saw a stoker sink down to the deck, a shell splinter driven into the back of his head. Another lad screamed in agony.The captain again gave permission to jump overboard. – Again a few tried it, only to be crushed on the reef. The captain, however, stood there among his men.’

‘His face showed that he was carrying the pain and suffering of all those about him. He looked at the enemy, and I believe that for an instant & look of supreme contempt passed over his countenance. Then he ordered that the German ensign be hauled down and a white flag hoisted. The firing ceased immediately.’

‘Later, two cutters were sent to us and the officer in charge stated that the Emden’s crew would be taken aboard the Sydney if Captain von Muller would give his word that none of his men would commit any unfriendly act. A boat was sent for the handful of men who had landed. They were brought back half mad from thirst and hunger. There had been neither water nor food on the island.’

‘On the Sydney the British sailors were all kindness. Our wounded were rushed to the operating room. Highballs revived us and we tasted the first food we had had in over 36 hours. That night our hosts, or captors, laid before us a wireless message containing editorial comment on the destruction of our ship.’

‘The London ‘Telegraph’ said: ‘It is almost in our hearts to regret that the Emden has been destroyed.’

In the 20 years that have passed, the verdict of the world has not changed, and the Emden has earned a niche in the hall of immortal ships.’

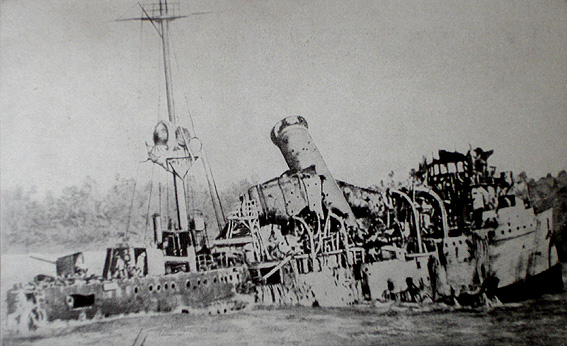

The wreck of SMS Emden. Taken from the book: Der Weltkrieg 1914-1918 in seiner rauhen Wirklichkeit. „Das Frontkämpferwerk“, Munich, ca. 1925

The wreck of SMS Emden. Taken from the book: Der Weltkrieg 1914-1918 in seiner rauhen Wirklichkeit. „Das Frontkämpferwerk“, Munich, ca. 1925

“Last of the Emden”

“LAST OF THE EMDEN.” Heytesbury Reformer and Cobden and Camperdown Advertiser (Vic. : 1914 – 1918) 25 December 1914: 3. Web. 27 Oct 2017 http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article152613086

‘//// Day A.B. on board the “Sydney,” and a relative of Mrs. Goodall of Cobden, gives the follow-ing thrilling account of the capture of the Emden: “On Monday morning we got a wireless from Coco Island station to say that a strange warship was blocking the entrance to the islands. We at once once raised steam on all boilers, and presently were streaming along at over 29 knots. The electrician came down and told me that the ship was in sight and that I could go and have a look, but he told me to come down again. Of course I was up on deck before you could “wisk(?) and away” ahead was an island, and between us and the island was a three funnelled cruiser, and she was steaming along to run out to sea.’

‘At the time we did not know that she was the Emden, but we were hoping and praying that she was. When we got within range, we turned and ran parallel to her, so that she was on our port side. We opened fire on each other, and the first shot that I saw fired by her hit the water about 20 yards short of us right in line with our bridge. Just after, I happened to be passing the foot of the bridge ladder, and saw two of our cooks’ mates struggling with something, and one of them beckoned me to them.’

‘It turned out to be an A.B.named Hoy, who worked the range finder on the upper deck. ‘A shell had struck the range-finder and carried it away, taking his left leg right off close to the body. He died just afterwards. A chap who was working with us at the ammunition hoist was struck in the chest with a piece of shell, and he die I on Wednesday. A shell burst near No. 2 starboard gun, and wounded all the gun’s crew except one man.’

‘The gunlayer died the next day, also an ordinary seaman. That made four fatalities and twelve injured. I finished up acting as one of the gun’s crew at No. I port, at the request of the gunlayer. You should have seen the Emden at this time. She was on fire aft, and only her main mast was standing, her funnels and foremast having fallen one at a time. Also she was getting very low in the water, and was evidently in a sinking condition. Her colours were still flying, from her main mast, arid as she was near an island, she headed and fast ashore.’

‘We ceased firing, and went off after a collier that was standing by the Emden. We took off all of the people from her, and then sank her. We then went back to the Emden, and signalled to her demanding her surrender. We’re received no reply, so opened fire again, but, after firing’ a few rounds, they waved a white flag, and one hand went aloft and took down her ensign. Our skipper sent off to the commander of the Emden that if he would guarantee good behaviour on the part of his officers and men, we would get his injured off, and take them all to Colombo. The Germans agreed, and we stood by them on Monday night, and on Tuesday we started to embark their wounded.’

‘One man; with his bead all bandaged, was brought aboard after dinner. On removing the bandages, we found that his right eye and all the right side of his face had been blown away. His nose was hanging down by a little bit of flesh, and his lower jaw was hanging by the left side. He had been like that for over 24 hours, and he lived till next night. Others were maimed in every conceivable place- broken arms, legs, parts of limbs blown off, and nearly every one of them was peppered with bits of shell and splinters.’

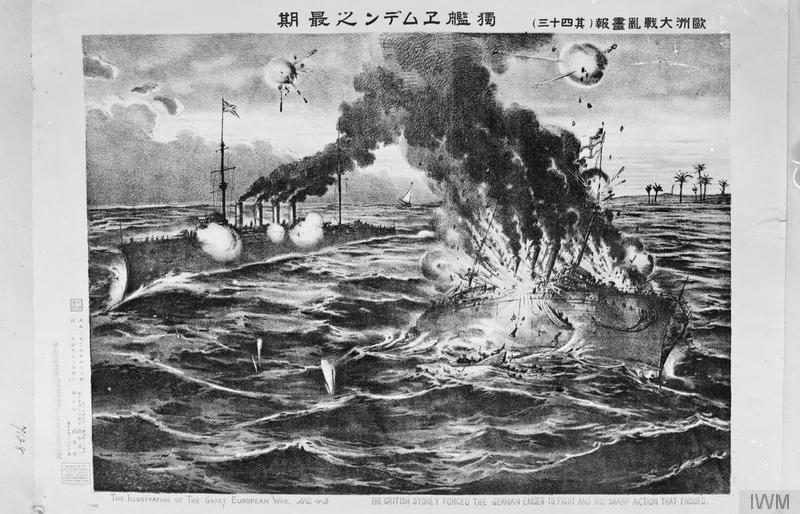

Imperial War Museum Galleries at the Crystal Palace, 1920-1924 A Japanese printed poster prdepicting the fight between the British light cruiser HMS Sydney and the German Raider Emden. In the IWM, Crystal Palace.

Imperial War Museum Galleries at the Crystal Palace, 1920-1924 A Japanese printed poster prdepicting the fight between the British light cruiser HMS Sydney and the German Raider Emden. In the IWM, Crystal Palace.

Captain Glossop describes Emden action to Banjo Patterson

`She had no idea that there was any vessel of her own power in that part of the Pacific, and she came out looking for a fight – and she got it. She must have got a surprise when she found she had to fight the Sydney; and I got a surprise, too, I can tell you. When we were about ten thousand five hundred yards apart I turned nearly due north so as to run parallel with her, and I said to the gunnery lieutenant that we had better get a thousand yards closer before we fired.’

‘I knew the Emden’s four-point-one guns would be at their extreme limit at ten thousand yards, and I got a shock when she fired a salvo at ten thousand five hundred and two of the shells came aboard us. That’s modern gunnery for you. Fancy one ship, rolling about in the sea, hitting another ship – also rolling about in the sea – six miles away! She must have elevated her guns and fired in the air, for we were technically out of range; but it was great gunnery.’

`Her first salvo was five guns, of which two shells came aboard us. One shell burst and carried away the after-control, wounding all the men, including Lieutenant Hampden, but no one was killed. The other shell passed within six inches of the gunnery lieutenant and killed a man working a range-finder, but it never burst. There was luck again for me – I was in that control and if the shell had burst I suppose I would have been a goner.’

`There was a boy of about sixteen in the control working a telescope.When the shell landed he was stunned by the concussion and was lying under the body of the man that was killed. As soon as he came to himself he threw the man’s body off him and started looking for his telescope. “Where’s my bloody telescope?” was all he said. That’s the Australian Navy for you.’

`The whole thing didn’t last forty minutes, but it was a busy forty minutes. She tried to get near enough to torpedo us, but she could only do seventeen knots and we could do twenty-seven, so we scuttled out of range. The Emden had a captured collier called the Buresk hanging about, trying to get near enough to ram us, and I had to keep a couple of guns trained on this collier all the time. We hit the Emden about a hundred times in forty minutes, and fourteen of her shells struck us but most of them were fired beyond her range and the shells hit the side and dropped into the water without exploding.’

`When the Emden made for the beach we went after the collier, but we found the Germans had taken the sea-cocks out of her so we had to let her sink. They were game men, I’ll say that for them.’

`Then we went back to the Emden lying in the shallow water and signalled her “do you surrender”. She answered by flag-wagging in Morse “we have no signal book and do not understand your signal.” I asked several times but could get no answer and her flag was still flying, so I fired two salvos into her and then they hauled their flag down. I was sorry afterwards that I gave her those two salvos, but what was I to do? If they were able to flag-wag in Morse, they were surely able to haul a flag down. We understood there was another German warship about and I couldn’t have the Emden firing at me from the beach while I was fighting her mate.’

`We waited off all night with lights out for this other vessel, but she never showed up, and then we sent boats ashore to the Emden. My God, what a sight! Her captain had been out of action ten minutes after the fight started from lyddite fumes, and everybody on board was demented – that’s all you could call it, just fairly demented – by shock, and fumes, and the roar of shells among them. She was a shambles. Blood, guts, flesh, and uniforms were all scattered about. One of our shells had landed behind a gun shield, and had blown the whole gun-crew into one pulp.’

‘You couldn’t even tell how many men there had been. They must have had forty minutes of hell on that ship, for out of four hundred men a hundred and forty were killed and eighty wounded and the survivors were practically madmen. They crawled up to the beach and they had one doctor fit for action; but he had nothing to treat them with – they hadn’t even got any water. A lot of them drank salt water and killed themselves. They were not ashore twenty-four hours, but their wounds were flyblown and the stench was awful – it’s hanging about the Sydney yet. I took them on board and got four doctors to work on them and brought them up here.’

https://www.navyhistory.org.au/captain-glossop-rn-describes-emden-action-to-banjo-patterson/

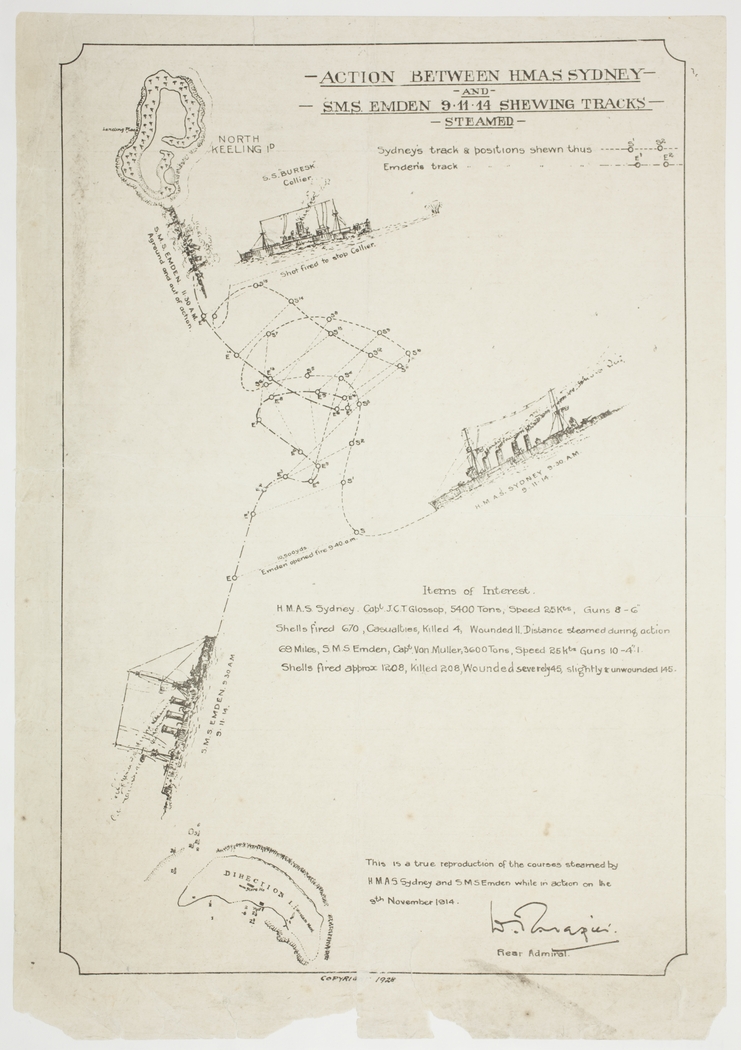

Map showing Battle of Cocos between HMAS Sydney and SMS Emden, 9 November 1914, Digital order number: a8553001 Source: SLNSW.

Map showing Battle of Cocos between HMAS Sydney and SMS Emden, 9 November 1914, Digital order number: a8553001 Source: SLNSW.

BY ONE WHO WAS THERE

The Sydney-Emden Fight (1917, July 24). The Richmond River Herald and Northern Districts Advertiser (NSW : 1886 – 1942), p. 3. Retrieved November 10, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article125931278

A Mid-Richmond soldier, now in the Moree Convalescent Home, forwards the “R.R. Herald” the following interesting article written by Torpedoer Ayres, a fellow convalescent, and published in the “North-West Champion,” Moree :

‘On a, certain Sunday in November, 1914, the first contingent of the Australian Expeditionary Forces was convoyed by H.M.A.Ss. Minotaur, Melbourne, Sydney, Pioneer, and a Japanese battle cruiser. The convoy was steaming in three single lines ahead, with H.M.S. Minotaur right ahead, scouting for any possible enemy. The Sydney was on the left, or port, side of the convoy, the Japanese cruiser on the right, or starboard, side of the convoy; with the Melbourne and Pioneer bringing up the rear. Everybody proceeded smoothly, and it was an imposing spectacle to see this grand fleet of transports being convoyed by warships. We could not keep our eyes off the Minotaur— it was magnificent to see her right ahead. First she would be going straight ahead; then all of a sudden she would go full speed ahead in one direction, and then go full speed in another.It was very pretty to watch her, even to a man-of-war sailor. But she was not, however, to be in command for long, for she received a wireless to proceed elsewhere. The Melbourne then took command. The Pioneer had already dropped back with some defect in her engines.’

‘All went well until the morning of the 9th of November, when a wireless message was received by the Orvieto (transport) and the Melbourne, from the wireless station at Cocos Island, as follows, viz.: “ Strange warship at mouth of harbor.” There was great excitement in the lines of the convoy. The Melbourne immediately signaled to us: “‘Sydney investigate,’ and away we dashed, gathering speed as we went; but at the time we could not help thinking we were on another wild goose chase. Everything was ready for immediate action. We had hardly put the finishing touches on, when away flashed the wireless — “ Enemy sighted.” We could see a ship on the horizon, coming towards us, and our captain challenged her. The reply was a salvo of projectiles, which pitched just in front of us. Then the sport began.’

‘The Emden was very lucky in the first ten minutes of the action, as one of her broadsides carried the range-finder away on the forebridge, and took the leg off the man manipulating it. Captain Glossop, who walked the bridge throughout the action, had a very narrow escape, as he was only a foot away from the finder when the projectile put it out of action. Tho same broadside also put our control and all the men in it out of action; so we were having a decent couple of minutes. Then the Sydney’s gun-layers got to work, and it was “hell” for the Emden ! We poured one

continual stream of lyddite into her —first one funnel went, then another, and then the other, and they seemed, the way they had fallen, to make a tripod. Then her foremast went; so she and her “ jolly” crew seemed to be having a “happy” time!’

‘The action went on, both ships steaming full-speed and manoeuvring for all they were worth. One shell had smashed through our forecastle, and in consequence the boys’ mess deck was full of water; but still the Sydney was doing 29½ knots, and the Emden about 26 knots. The nearest we got to the Emden was 4500 yards; and then smacked a torpedo at her; but there was not much chance of torpedoing her, as she was very ‘slippery.’ After the action had lasted an hour and forty minutes, the Emden was seen to turn and make for the shore where von Muller put her, so as not to lose all his men. When we had seen her ‘‘safely’‘ on the beach, we proceeded after the collier, “Buresk,” which had a German prize crew aboard. We overhauled her as she was trying to get away, and put a shot across her bows, which made her heave to, and we took the crew off; but they had opened the Kingston valves, so we had to put a couple of shells into her and sink her. We then proceeded back to see how the Emden was getting on, and we saw that she still had her battle flag flying from the main truck.’

‘We thought von. Muller was still defiant, so we gave him a couple of broadsides, and then a white sheet was seen to flutter from the forecastle. We ceased firing, and left the Emden for the day and went in search of more trouble, as we thought the Konigsberg was acting in conjunction with the Emden; so we prepared to receive her and give her some of the same ‘rations’ we had given the Emden. Whilst cruising about we picked up two of the quarter-deck gun’s crew of the Emden – they had been blown clean over the side, and had been in the water for five hours. One was inside a life-buoy, and the other was being supported by him. We could not help giving him a cheer, and they shouted, “Thank you!” in good English. Nothing happened that night, and the next day we proceeded to get the wounded off the Emden.’

‘During the two days we were there, we had a trying time, for some of the Emden ‘screw swam through the surf and were roaming round the island (Keeling Island). We had to send a landing party to round them up. Some of them were found on the beach, dead — they swam through tho surf, only to die on the beach, and the crabs and scavenger birds had been feeding on them. After everything was ready, we proceeded full speed to Colombo, and got the wounded ashore, also the prisoners. We treated them with every kindness, and left on our way to Gibraltar, where we had a new control and range-finder put into the ship. We left Gibraltar on Xmas Eve, 1914, and made for the South Atlantic, where the German raiders were operating.’

‘The next news we got from tho outside world was in May, 1915, after the two Atlantic raiders had been accounted for. From August, 1914, till the end of December, 1915, the Sydney had covered 116,000 miles. Pte. Lawrence Brown, who has just returned to Grafton from France and Belgium, writes to the “ Daily Examiner” to say : I am astonished at the lack of interest shown by my fellow- Australians whom I, together with others, having been keeping in ease and comfort. It’s hard to keep going over there when your own kith and kin out here are turning you down. All the other chaps from Canada, South Africa, and other parts of the Empire get the backing of their mates at home — why don’t we get it? Some people say here that men are not wanted. God, what folly! Anybody who says such a thing is a fool and a liar. Men are wanted, and put the “men” in big letters. Half the reinforcements that we have been receiving are just mere boys, and they are being slaughtered because the men of Australia will not do their duty.

Will you listen to a man that has fought for you? Will you believe him when he tells you that unless men do come forward, the name of Australia will “stink” for all time?’

The ‘Emden’ Gun 039\039864 ADDRESS Liverpool, Oxford & College Streets. DESCRIPTION World War I vintage photograph. DATE c 1917 FORMAT B&W postcard RECORD SERIES Sydney Reference Collection CITATION SRC13467. Originally CRS 44/118. PROVENANCE City of Sydney Archives

The ‘Emden’ Gun 039\039864 ADDRESS Liverpool, Oxford & College Streets. DESCRIPTION World War I vintage photograph. DATE c 1917 FORMAT B&W postcard RECORD SERIES Sydney Reference Collection CITATION SRC13467. Originally CRS 44/118. PROVENANCE City of Sydney Archives

Follow the Sydney_Emden… story

After Cocos: Sydney-Emden memorial unveiled!

After Cocos: HMAS Sydney’s progress

After Cocos: Holsworthy Concentration Camp

Sydney v Emden, a century later

HMAS Sydney’s mast dedication, 80 years ago today

Sydney’s mast not destined for ‘Sow and Pigs’

Footnotes

1 50 of the landing party stranded on Direction Island made a daring and arduous escape.

2 NSW Migration Centre The enemy at home : German internees in World War 1 Australia; Holsworthy Internment Camp: retrieved online http://www.migrationheritage.nsw.gov.au/exhibition/enemyathome/holsworthy-internment-camp/index.html

3 Ibid

4 Ibid

5 Ibid

6 Ibid

7 Ibid

8 Ibid

Children’s toys and model Fokker ‘Eindecker’, made by internees in 1916 and 1917, Trial Bay Gaol collection. Photograph by Stephen Thompson

Children’s toys and model Fokker ‘Eindecker’, made by internees in 1916 and 1917, Trial Bay Gaol collection. Photograph by Stephen Thompson