After leaving SMS Emden ‘wrecked and done for’ in 1914, HMAS Sydney served with the British North Sea fleet.

Sydney was involved in some interesting engagements under her new commander, Captain Dumaresq.

Dumaresq was a man of exceptional ability and vivid imagination—an originator, both of novel devices and of tactical ideas. When he joined the Sydney he was in the thick of a campaign for inducing the Admiralty to use light cruisers against the Zeppelins which were at the time infesting the North Sea area—a scheme which in the end involved the installation of launching-platforms for aeroplanes on the cruisers.1

Sydney vs. L43

Charles Bryant’s 1931 painting depicting the HMAS Sydney a the fight with Zeppelin L43 in the North Sea.

Charles Bryant’s 1931 painting depicting the HMAS Sydney a the fight with Zeppelin L43 in the North Sea.

On the 4th of May, 1917, the Cruisers Sydney , Dublin and four Destroyers fought a running duel with German submarines and a Zeppelin.

Dumaresq was aware his ships could be drawn into a U-boat trap by Zeppelin L43 floating ominously above them at 7000ft., observing every move.

The Cruisers turned their attention to the strange craft in the skies, elevating guns and unleashing a torrent of fire.

This angered the Zeppelin into a direct attack:

The helium-filled behemoth took immediate evasive action, ascending out of range, then manoeuvred itself into a position to bomb the convoy.

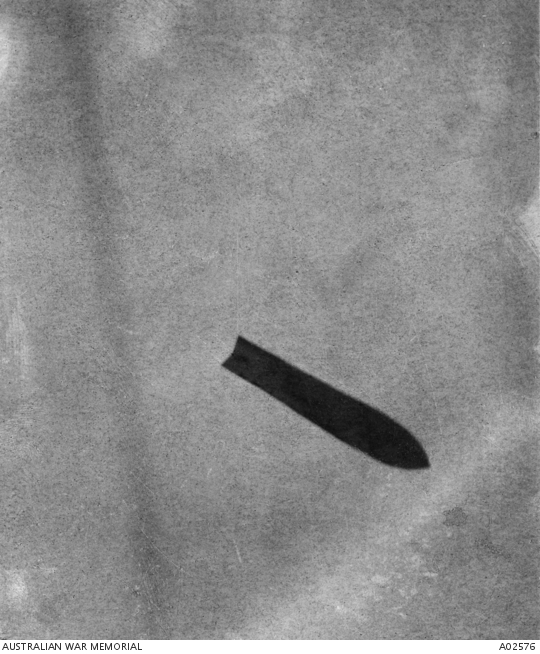

The German Zeppelin L43, photographed by Able Seaman G Leahy, who lay on his back while HMAS Sydney was being bombed by 10 bombs each weighing 250 pounds.

The German Zeppelin L43, photographed by Able Seaman G Leahy, who lay on his back while HMAS Sydney was being bombed by 10 bombs each weighing 250 pounds.

A cat-and-mouse engagement ensued:

Dumaresq became probably the first naval officer to develop the zig-zag system of bomb avoidance. For almost two hours he weaved in evasive action.

The fight was inconclusive. L43’s bombs landed harmlessly in the ocean.

…it flew above the Sydney and dropped ten or twelve bombs, six of them in two salvoes; then, the Sydney having used up all her anti-aircraft ammunition’ and the L43 all its bombs, “the combatants,” to quote an officer who was in the fight, “parted on good terms.”2,3

According to the Australian War Memorial Sydney ‘s actions against L43 made her

the first Royal Australian Navy vessel to be subjected to an air attack.

This article is an excerpt from: After Cocos: HMAS Sydney’s progress

Follow the Sydney-Emden story

After Cocos: Sydney-Emden memorial unveiled!

After Cocos: HMAS Sydney’s progress

After Cocos: Holsworthy Concentration Camp

Sydney v Emden, a century later

HMAS Sydney’s mast dedication, 80 years ago today

Sydney’s mast not destined for ‘Sow and Pigs’

1 Jose, Arthur W. The Royal Australian Navy 1914-1918, Sydney: Angus & Robertson. (1928)

2 Zeppelin L43 was later shot down by an RNAS flying boat:

3 AWM First World War Official Histories – Volume IX – The Royal Australian Navy, 1914–1918 9th ed., 1941. p 295-300. retrieved online 21/01/18 https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/C1416827.

Appendix: Description of the battle by CEW Bean

First World War Official Histories Volume IX – The Royal Australian Navy, 1914–1918 (9th edition, 1941) Chapter X – Service in European Waters:

4th May, 1917 EUROPEAN WATERS p. 295 –

Dumaresq was a man of exceptional ability and vivid imagination—an originator, therefore, both of novel devices and of tactical ideas. When he joined the Sydney he was in the thick of a campaign for inducing the Admiralty to light cruisers against the Zeppelins which were at the time infesting the North Sea area-a scheme which in the end involved the installation of launching-platforms for aeroplanes on the cruisers. Various experiments along these lines made the Sydney’s next few months of service particularly interesting. On the 3rd of May the Sydney, with the Dublin and four destroyers (Nepean, Obdurate, Pelican, Pylades, left Rosyth for a sweep along certain cleared channels between the mouths of the Forth and the Humber; three destroyers in line abreast did the sweeping with their anti-submarine paravanes), the cruisers and the Obdurate (whose paravanes were out of order) following. About IO a.m. on the 4th the southward sweep was completed, and the six ships turned north-north-west towards Rosyth at eighteen-and-a-half knots. Five minutes later a small vessel was sighted east-wards, and the Obdurate was sent to examine her.

At 10.25 a.m. the Dublin observed a Zeppelin (afterwards ascertained to be L 43) about seventeen miles away to the east, rapidly approaching the strange vessel; both cruisers promptly made for the enemy, opening fire on it at extreme range and ordering the three destroyers to cut their sweeps loose and follow in support. The Obdurate, meanwhile, had been attacked by a submarine just as she reached the suspected vessel, and at 10.30 sighted another about 1,000 yards away; she dropped two depth-charges near the first and one near the second, sighted the distant Zeppelin and started independently in chase of it. As soon, however, as she got within four miles of it, it rose steeply and sheered off to the south-east. The cruisers now had their turn. At 10.54 the Dublin saw the track of a torpedo passing ahead of her, at 11.12 a submarine, and at 11.15 another, which fired two torpedoes at her.

At 11.20 she sighted a third, which she engaged with her guns and on which she dropped a depth-charge. Dumaresq (who was in command of the whole British force) came to the conclusion that he was being deliberately led into a sub-marine-infested area; recalling his companions, he resumed his original course to the north-north-west, at the Same time signalling to the Obdurate to board the suspect from which she had been lured away:

If there is any presumption whatever of connection with Zeppelin and submarines, you are to sink her and take back crew with you.”

Seeing the British ships in apparent retreat, the Zeppelin took heart and came after them. Dumaresq at once spread his ships, the cruisers maintaining their course, the Pylades making north-east to join the Obdurate, the Pelican and Nepean diverging south- west to get behind the airship, that soon after noon it was technically “surrounded.” At 12.10 the cruisers doubled back on their tracks, bringing the L43 within 7,000 yards range at an elevation variously described as fifty degrees and eighty degrees, and opened fire.

This angered the Zeppelin into a direct attack: making for the stern of the Dublin, and rising hastily as it flew, it endeavoured to attain a position vertically above the cruiser in order to drop bombs on her-an attempt which was foiled by the Dublin ’s hurried swerve to starboard. The Zeppelin thereupon flew above the Obdurate (which had completed her examination of the suspected vessel) and from a height of about 20,000 feet dropped three bombs within thirty feet of her, splinters coming aboard; twenty minutes later it flew above the Sydney and dropped ten or twelve bombs, six of them in two salvoes; then, the Sydney having used up all her anti-aircraft ammunition and the L 33 all its bombs, “the combatants,” to quote an officer who was in the fight, “parted on good terms.”

During the latter part of the fight L43 used its wireless vigorously, and a little before 1 p.m. another Zeppelin was seen far off in the north-east, but by 1.10 both had disappeared eastwards.’This fight well illustrates the defects of the Zeppelin as an instrument of aggression. Airships can rise quickly and fly fast, but, compared with cruisers and destroyers, are slow in lateral steering; their plan of attack, therefore, when once an enemy ship is sighted, is to fly high out of range while observing her course and speed, and then, manoeuvering into a position well astern of her, to catch her up and bomb her while flying directly above. Obviously, the vertical height should not be too great, or bombing becomes a matter of chance. The attacked ship has two main defences -sudden alterations of course, especially when the airship is just about to get into bombing position, and steady anti-aircraft fire, which, though it has little chance of inflicting actual damage, compels the airship to keep to a great height. Dumaresq’s method of fighting the Sydney mas in accordance with these principles:

During the latter part of the action, the Sydney manoeuvred to prevent L43 from coming up astern, by keeping her on or before the beam, turning often, whereby L43 was obliged to drop her bombs while crossing Sydney’s track. The gunnery officers of Sydney and Dublin made very good shooting with the H.A. guns, thereby keeping the airship at such a height as to make her bomb-dropping inaccurate.

In the footnotes Bean mentions:

An interesting and racy account of this action furnished by an eyewitness, J W Seabrook, who at the time of the fight was a leading signalman and stationed on the bridge of the Sydney, is given in Appendix No. 24.

Appendix 24 – An interesting and racy account

SYDNEY IN NORTH SEA p 589

ACTION WITH ZEPPELIN L43.

On Thursday, 3 May 1917, H M.A.S. Sydney, H M S Dublin , and eight destroyers, under; the leadership of Captain Dumaresq, left Rosyth with orders to sweep L Channel, which was approximately 120 miles long. On his occasion, also, as the ship passed under the Forth Bridge there was no train on the, bridge, and the word soon went round – “What’s going to happen?” Nothing of any note occurred until 10.28 am. on Friday, 4 May, when H.M.S. Dublin reported having been fired at by a submarine, the torpedo missing astern. The destroyer Obdurate next reported a submarine, and the Sydney and Obdurate steamed over the spot and let go depth charges. At 10.30 a.m. the signalman of the watch on board H.M.A.S. Sydney reported:

Zeppelin right ahead, sir.

A Zeppelin, which we subsequently learned was the L43, had been sighted. Captain Dumaresq immediately ordered full steam (25 knots), and his plan of action was as follows: to rush at the Zeppelin and fire a 6-inch gun, with the object of making the Zeppelin engage the Sydney. Immediately the Zeppelin was sighted Captain Dumaresq thought that it was working in conjunction with U-boats, the Zeppelin doing the scouting and the U-boats the sinking Of British merchantmen. With this thought in mind, the captain of the Sydney did not intend to rush in too far. It seemed obvious that the Sydney sighted the Zepp. first, because on the Sydney’s 6-inch projectile landing in the water, the Zeppelin stuck its nose up and tail down and rose rapidly. Here I may explain that the Germans claimed that their Zeppelins could rise at a speed of 500 feet per 30 seconds. The Zeppelin continued to rise and turned away, either because she did not want to fight or else to draw the Sydney on in order to get her to steam over the position on the water that the Zeppelin had been manoeuvering, which was thought to be a submarine nest or rendezvous. If such was the game, it failed, because as soon as Captain Dumaresq thought he saw through the Hun manoeuvre he turned and ran away from the Zeppelin. As soon as the Zepp. saw this move it turned around and chased the Sydney , which was exactly what that good ship wanted.

Just before the Zeppelin overtook the Sydney , Captain Dumaresq ordered “open fire” with the anti-aircraft shots from the Sydney went as straight as a gun-barrel for the Zepp. amidships, leaving a thin trail of smoke in their wake, and appeared to anxious eyes on the deck of the Sydney to reach their culminating point not many feet below the undercarriage of this mighty Zepp. Groans went up when it was realized that the Zepp. could have it all its own way by keeping outside the Sydney’s anti-aircraft vertical range of 21,000 feet, and take its time letting go whatever bombs it had on board. Captain Dumaresq recognised this point and tried just one more ruse to “kid” the Hun to come a little lower.

The manoeuver “to scatter” is used for several reasons, but had never before been used for Captain Dumaresq’s reason. On the order “scatter” all ships turned away from the Sydney and, selecting a point on the horizon, set their various courses and steamed outwards at full speed. The result of this was that the Zepp. and the Sydney were left to it, and the remaining ships were in a complete circle round them but steaming away. Captain Dumaresq hoped that, when the Sydney ordered the remaining ships apparently to run away, the Zepp. would close down on the Sydney in order to have a good shot at her with some heavy bombs.

As soon as the Zepp. commenced to come down, the Sydney hoisted the “ recall” to all ships and to “open fire.” The result of these signals was that the Zepp. was the centre at which shells from one light cruiser and eight destroyers were coming, the height of the Zepp. being at one time 14,000 feet. She immediately rose to a safe height and then began to act. Her first bomb of 250 pounds missed, off the Sydney’s port bow. The second missed, also off the port bow but nearer. The Sydney altered course and steamed over where the second bomb fell. The third bomb missed and dropped off the starboard bow.

The Sydney straightened her course. The Zepp. then let go three bombs in “rapid fire” which straddled the Sydney , two dropping to starboard and one to port. Had the Sydney repeated her manoeuvre of steaming never where the last bomb fell, I would not be able to finish this story. The Sydney next altered course to starboard, this time over where the nearer of the last two bombs to starboard fell. The Zepp. let go two more bombs “rapid fire,” missing with both (off the port bow) and causing Captain Dumaresq to say:

The Sydney again steamed over the point where the next of the !xt two bombs had dropped, and the Zepp. again let go of yet two more bombs, which duly missed – off the starboard. After the Zepp. had let go her third bomb, the destroyer Obdurate joined up with the Sydney and asked for orders. Captain Dumaresq replied:YOU can’t drop two in one place, old chap.

Follow me round.

Then, with his back up against the bridge screen, his feet on the base of the compass, and intently watching the Zepp., he remarked:

This fellow is doing some good shooting, but he won’t damn well hit us.

The signalmen of the Sydney had huge grins all over their faces because they thought the little destroyer was absolutely bound to get all the “overs”- that is to say, those bombs that missed the Sydney by dropping astern. However, good fortune or the God of Justice or the Sydney ’s manoeuvring favoured the little Obdurate, because all she got were two punctures in her funnels and no one wounded. He ordered all ships to “scatter.” rapid fire while the Zepp. Was bombing the Sydney , the commander of the Sydney was driving would-be spectators down a hatchway under cover. At the same time, others were pouring up another hatchway to see all the fun.

A second Zeppelin, which had been sighted during the bombing, had by this time joined up with the first, and signalling commenced between them. As it was most galling to see the Sydney ’s projectiles going straight for the Zeppelins and,then turning over before reaching them, Captain Dumaresq ordered “Cease fire.”

The crew of the Sydney now said their good-byes, thinking they had no chance in life of having the good luck to dodge another round of bombs. However, after five minutes both Zeppelins turned towards the German coast, much to the relief of all concerned, and sailed for home. The Sydney , Dublin , and destroyers now finished the interrupted work of sweeping L” Channel, and returned to Rosyth.

To show how monotonous the members of the Sydney ’s ship’s company considered life in the North Sea, I will relate an incident which happened about four days after this action. On return to harbour four hours’ leave was given. A certain stoker who failed to return on board was arrested three days later and was brought before Captain Dumaresq on a charge of desertion. When asked what he had to say, he answered:

I’m fed up, sir. Nothing ever happens.

Captain Dumaresq said:

Nothing ever happens! Why you just had a fight with a Zeppelin; isn’t that something happening?

The stoker replied in a most lugubrious voice:

Not one of ’em hit us, sir.