Headline story for the ‘Brisbane Daily’ 10 June 1928. Source: Trove

Headline story for the ‘Brisbane Daily’ 10 June 1928. Source: Trove

At 10.50 am, June 9, 1928, resident Norman Ellison was an eye-witness to one of the greatest moments in Australian aviation. But from his angle (and the crowd present) all of the four flyers deserved a warm Aussie welcome, not just their hero Smithy. Norman Ellison made sure of it…

09/07/1928

Brisbane arrival 10.50 a.m.

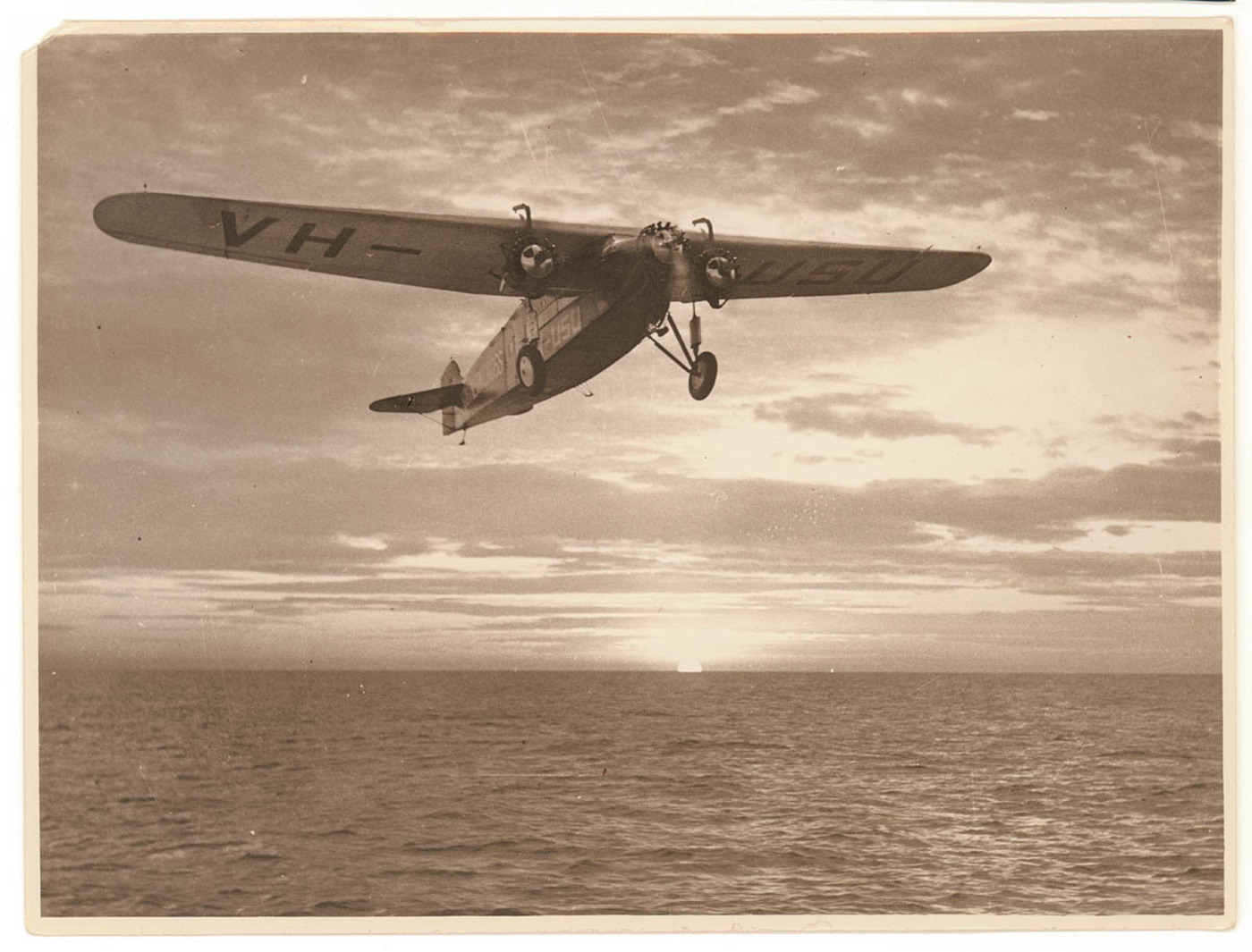

‘Southern Cross’ landing at Brisbane airport 1928 Source: StateLibQld 1 139254

‘Southern Cross’ landing at Brisbane airport 1928 Source: StateLibQld 1 139254

Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm, co-pilot, circled the Southern Cross into Brisbane after the epic flight in their ‘old bus’ across the Pacific. Two Americans Harry Lyon, navigator, and radio operator Jim Warner sat behind the pilots, separated by a huge fuel tank. Warner had messaged enthralling updates to captive audiences, and Lyon had guided them successfully over the vastness to Hawaii and Fiji.

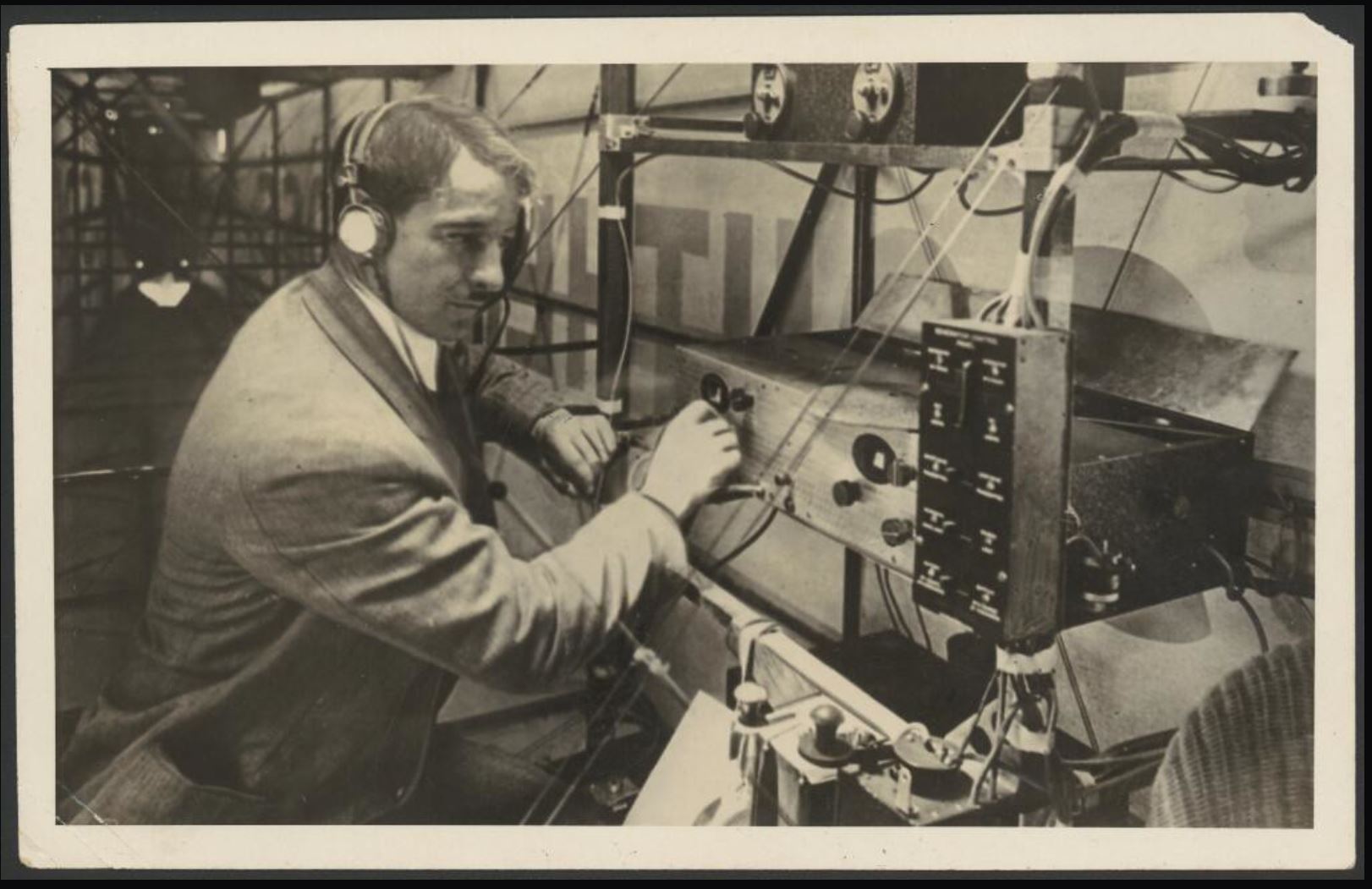

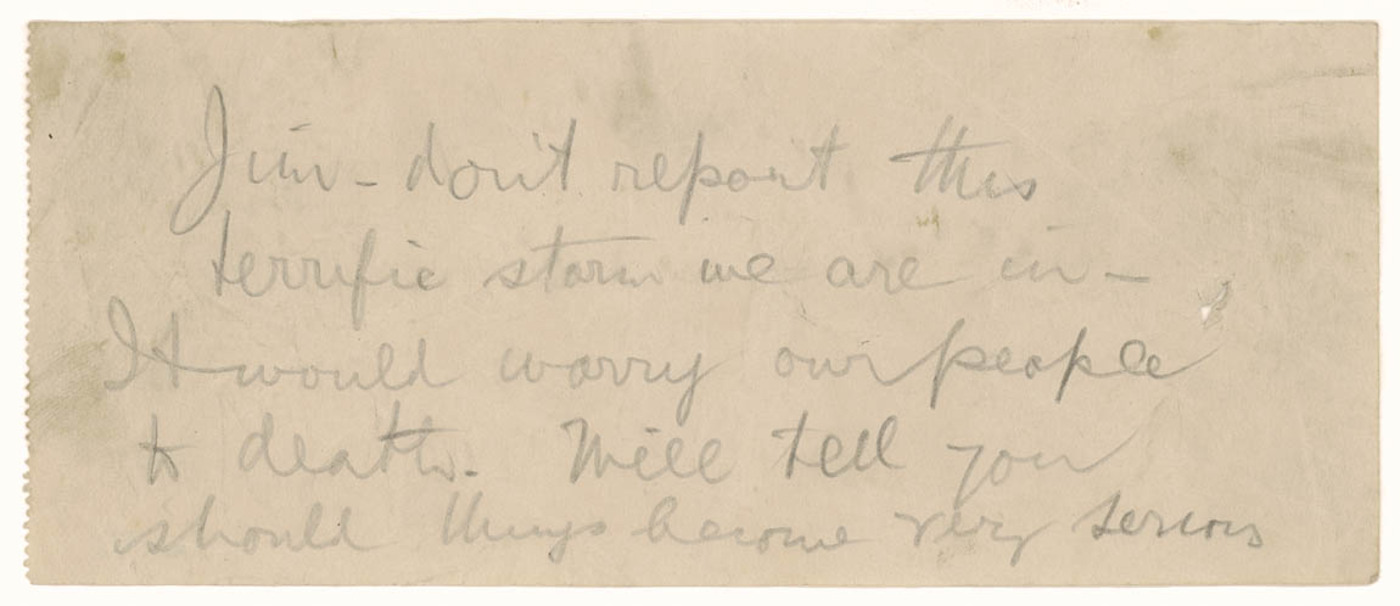

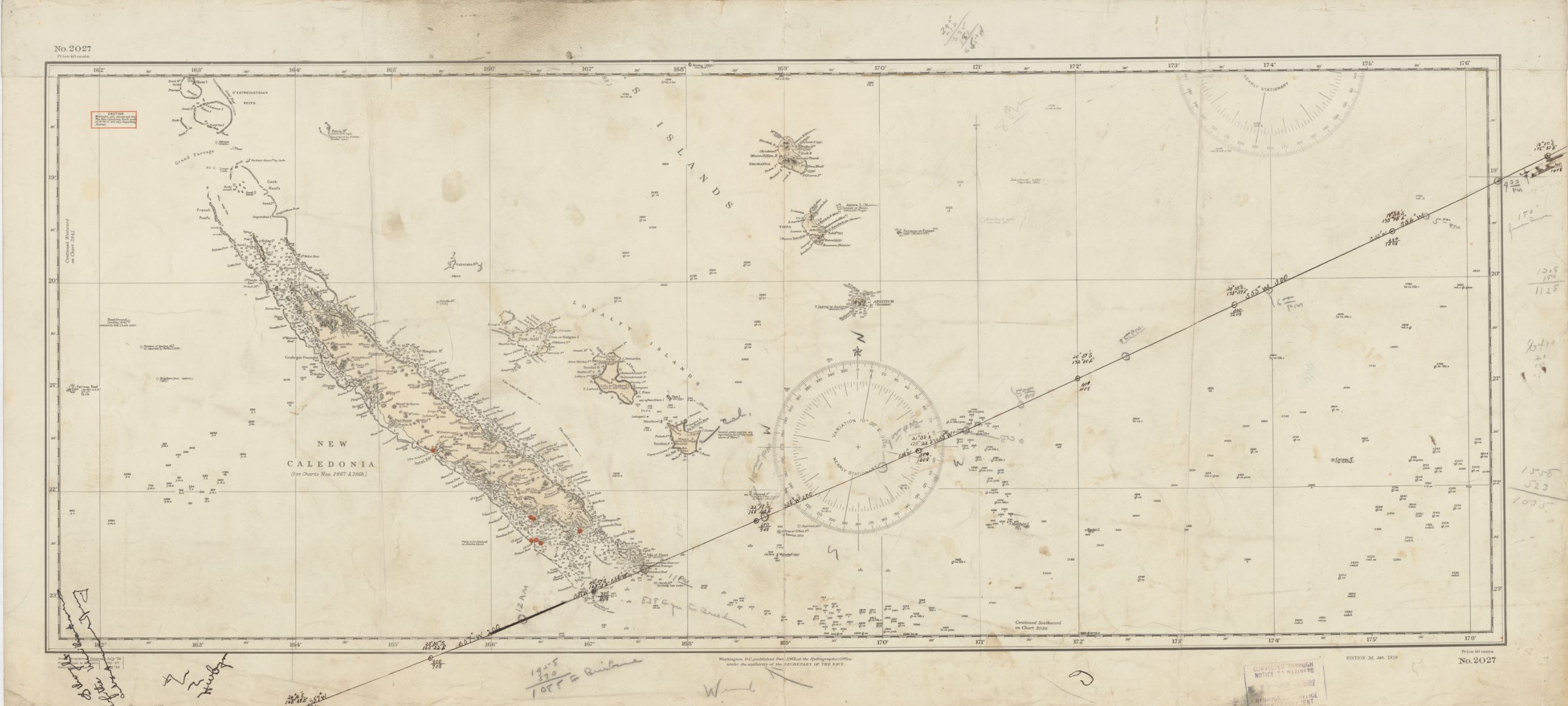

Top Jim Warner the man ‘on the keys’. Sitting amongst radio equipment. The antenna trailed behind the bottom of the aircraft. Note the thin canvas exterior, which Warner revealed he fell through on landing in Fiji- they found him unconscious and naked near the aircraft, lucky to be alive. Source: Michael Molkentin; Photo: NLA https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147658361/view. Middle: Hand-written note from Ulm not to report severe storm Source:The Charles T.P. Ulm collection of historical aviation records, Part 1, 1919-1965 Source: MLMSS 3359 SAFE/MLMSS 3359 (Safe 3/127) Bottom: Harry Lyon chart map with hand-drawn flight course. Accurate navigation was a matter of life or death. Source: NLA https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1267331665/view

Top Jim Warner the man ‘on the keys’. Sitting amongst radio equipment. The antenna trailed behind the bottom of the aircraft. Note the thin canvas exterior, which Warner revealed he fell through on landing in Fiji- they found him unconscious and naked near the aircraft, lucky to be alive. Source: Michael Molkentin; Photo: NLA https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-147658361/view. Middle: Hand-written note from Ulm not to report severe storm Source:The Charles T.P. Ulm collection of historical aviation records, Part 1, 1919-1965 Source: MLMSS 3359 SAFE/MLMSS 3359 (Safe 3/127) Bottom: Harry Lyon chart map with hand-drawn flight course. Accurate navigation was a matter of life or death. Source: NLA https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1267331665/view

last to descend… [?]

Local resident Norman Ellison was there, on the spot. Jostling with rival ‘Journos’ and a heaving mob gathered to congratulate the four airmen.

Somewhere in the relay of what was seen, and what went to print, a key moment was not reported. But here’s what one paper reported1

Immediately on landing the ‘plane taxied smoothly to the enclosed barricade. Around the sides of flimsy pine barricades, the excited crowd surged and jostled, cheering wildly as the smiling face of Kingsford Smith appeared above the cockpit, one hand guiding the great ‘plane to a standstill while with the other he waved a cheery greeting to the crowd.

Before the ‘plane had stopped, the crowd, in blithe disregard of the whirling propellers, closed in on the machine in a wild rush to gain a closer glimpse of the aviators as they prepared to climb out of the machine.

Crowds gather at the Brisbane Airport to watch the landing of Charles Kingsford-Smith in Brisbane. The words ‘Southern Cross’ are written on the side of his plane. Source: Brisbane John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

Crowds gather at the Brisbane Airport to watch the landing of Charles Kingsford-Smith in Brisbane. The words ‘Southern Cross’ are written on the side of his plane. Source: Brisbane John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland

‘Hello Aussies’: Smithy alighting and inhaling a ciggy ‘with luxurious enjoyment’. A pleasure all crewmen craved. Source: SLQld https://hdl.handle.net/10462/deriv/127957

‘Hello Aussies.’

Kingsford Smith was first to climb out of the machine, and he acknowledged the cheers of the crowd with a smile and a shout: “Hello, Aussies.”

He was followed by Ulm and both demanded cigarettes and inhaled them with luxurious enjoyment.

The navigator Lyons, who is the wag of the party remarked: “Waal, Jim, we’ve travelled 7000 miles to get a drink.” His fellow-American, Warner, who flashed out Morse messages during the memorable flight, was last to descend, and when he leaned against the side of the Southern Cross to get his land legs [Author highlight] his battered hat was askew, and he smiled, embarrassed by the warmth of the crowd’s welcome. He and Lyon, who were both clad In blue serge suits, were quietly and un-ostentatiously withdrawing behind the two figures of Kingsford Smith and Ulm, conspicuous for their heavy airmen’s uniform and helmets when the crowd pounced on them, and with a cheer hoisted them shoulder high, crying: “Good old Yank.”

Other members of the party were also being enthroned on willing shoulders, the men carrying Warner took him over to the barrier until he looked over the sea of faces, and shouted: “Have a look at him; he’s the boy that worked the keys.”

Crush of people welcoming Kingsford Smith, Brisbane, 1928. Source: Brisbane John Oxley Library, State Library of Qld 81-5-11 Author’s note: the look from Ulm captured here as he notices the Americans being brought in by the crowd is interesting, in the context of this story.

Crush of people welcoming Kingsford Smith, Brisbane, 1928. Source: Brisbane John Oxley Library, State Library of Qld 81-5-11 Author’s note: the look from Ulm captured here as he notices the Americans being brought in by the crowd is interesting, in the context of this story.

I managed to convince them…they, too, were to be guest of honour

Norman Ellison saw it different, and as a result, Warner and Lyon feature in what happened next:3

After circling the aerodrome, the Southern Cross came in. At the end of its landing run, the plane stopped briefly.

Two men jumped out and began to walk away from, not towards, the reception enclosure.

‘Brisbane Daily’ 10 June, 1928. Source: Trove

‘Brisbane Daily’ 10 June, 1928. Source: Trove

Norman ran out to the two men and identified himself as a reporter:

The chunky chap fumbled with a handkerchief, took out a denture, slewed it into his mouth, and said, “I’m Harry Lyon, and this is Jim Warner.” After handshakes, I asked, “Why did you leave the plane? And where are you going?” Lyon said this was an Australian welcome for two Australians, so he and Warner were keeping out of it. I managed to convince them they were wrong – they, too, were being welcomed; they, too, were to be guest of honour at the official enclosure.

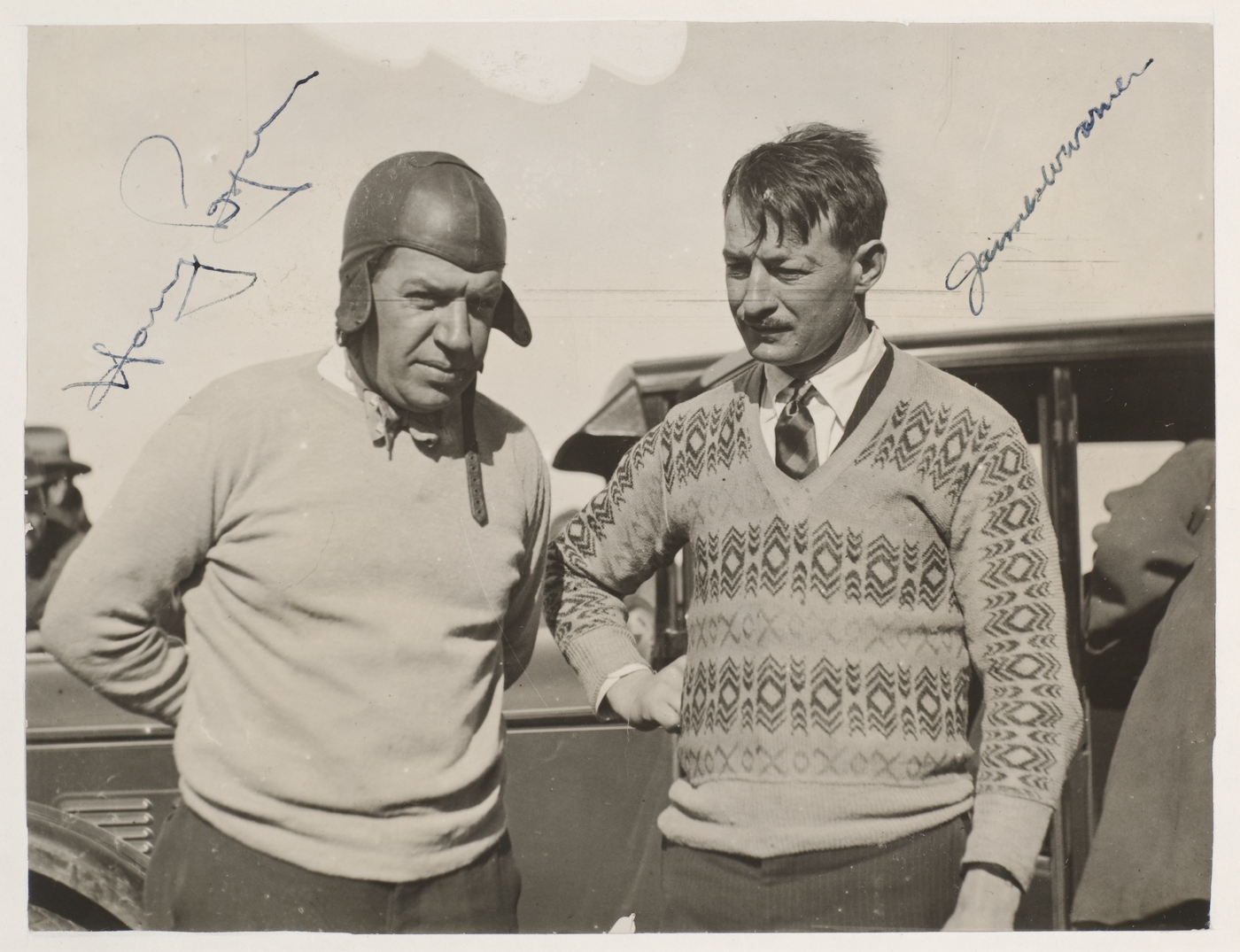

Picture showing two men leaving the ‘Southern Cross’ before at the end of the runway. Enlargement shows them to be Lyon and Warner (with distinctive white hat and suits). From ‘Brisbane Courier Mail’ via Ian Mackersay.

Picture showing two men leaving the ‘Southern Cross’ before at the end of the runway. Enlargement shows them to be Lyon and Warner (with distinctive white hat and suits). From ‘Brisbane Courier Mail’ via Ian Mackersay.

The two Americans went back towards the enclosure. Before they got there, they were identified by the crowd in the vicinity and enthusiastically welcomed. All four airmen were acclaimed at the official ceremony at the airport and drive through the city.

People lined up along a Brisbane street to see Sir Charles Kingsford Smith, 1928. Source: Brisbane John Oxley Library, State Library of Qld 86-7-4

People lined up along a Brisbane street to see Sir Charles Kingsford Smith, 1928. Source: Brisbane John Oxley Library, State Library of Qld 86-7-4

The Scoop

…unexpected, astonishing news.

Late that afternoon Norman waited in the hotel lounge Smithy, Ulm and were staying at, still perplexed at why the Yanks had been kicked out of the plane:

…unexpectantly, Lyon joined me. He was spruce, fit and ready for fun. When he said how deeply he’d been impressed by the warmth of the public welcome I said that was only the beginning – “you wait till you get to Sydney”. They wouldn’t be going there said Lyon; he and Warner were remaining in Brisbane until they took the first ship back to the States. That was unexpected, astonishing news. It didn’t make sense, I said, for the really big national welcome would be at Sydney, and the two Americans just had to be there. Surely they weren’t in such a hurry to get home, and anyway in the Southern Cross, Sydney was only a few hours away. And the welcome would not just be for two Australians, but just as much for the other members of the crew.

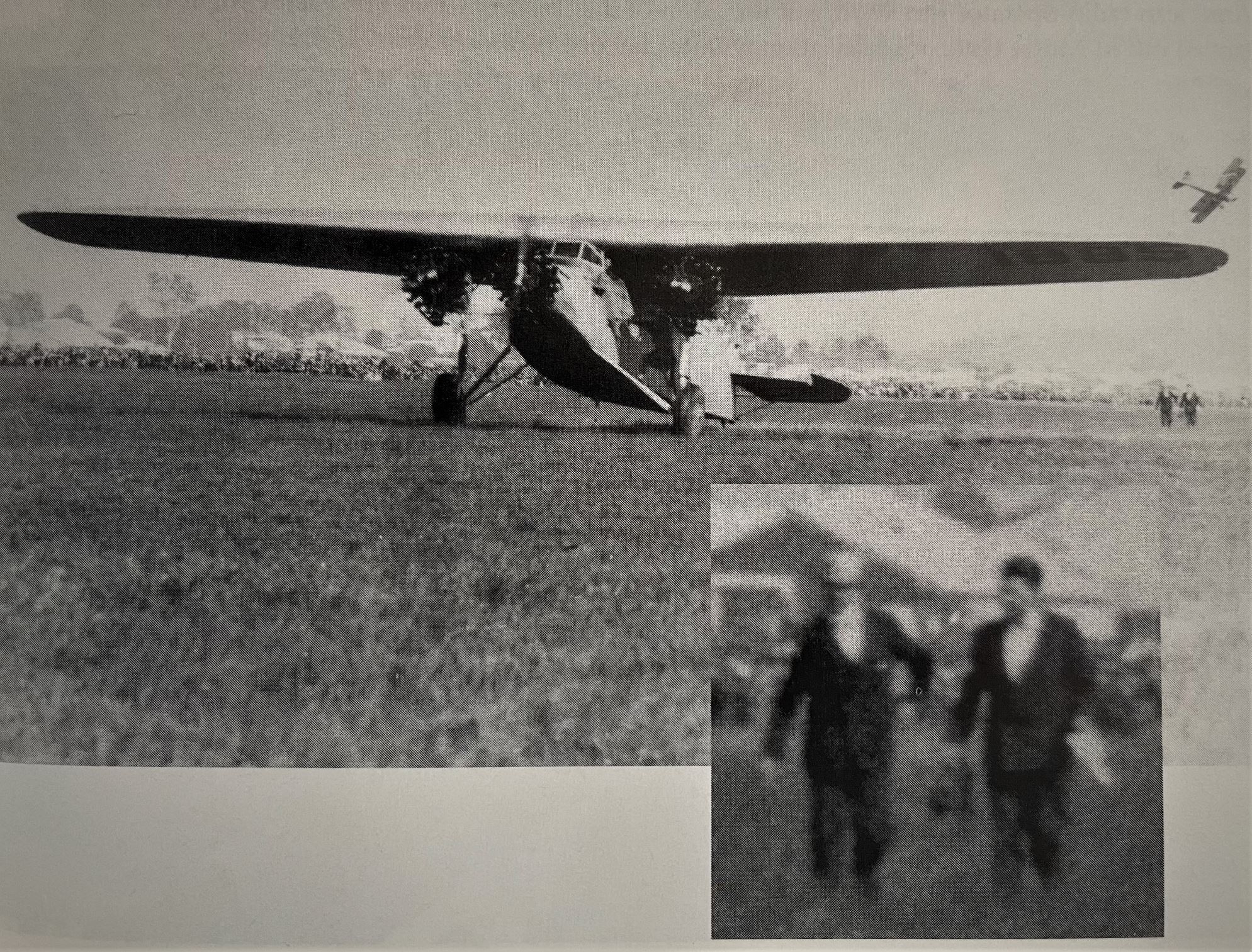

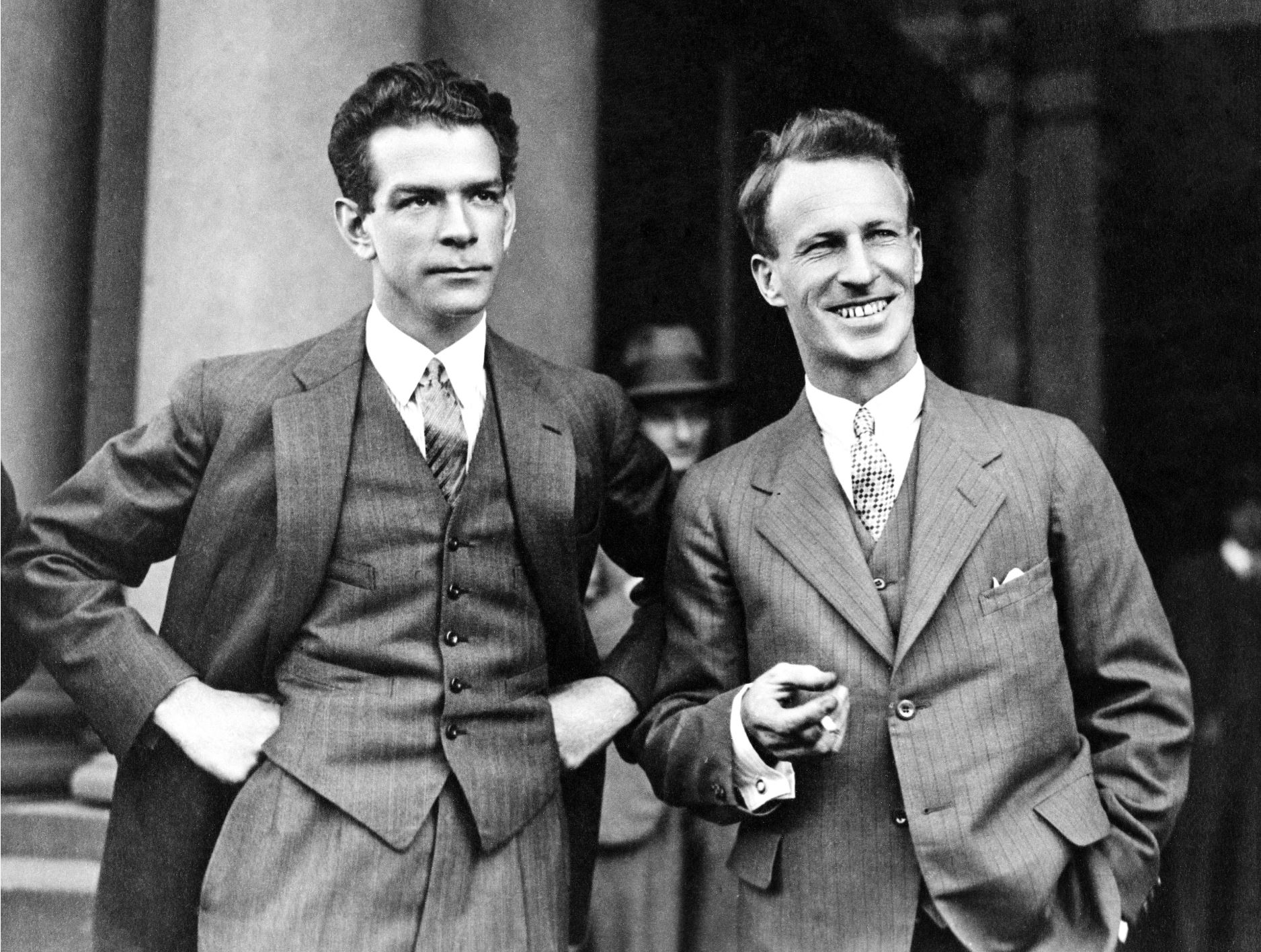

Harry Lyon [navigator] and James Warner [radio operator], 1928 / photographer unknown Source: SLNSW FL3194924

Harry Lyon [navigator] and James Warner [radio operator], 1928 / photographer unknown Source: SLNSW FL3194924

Lyon explained why they couldn’t be part of the Sydney welcome:

Their contract ended with the arrival in Brisbane, he said. Besides, he admitted frankly, at Suva he had been drunk, he had blotted his copybook, and Ulm, who had arranged the flight contract, had said that he and Warner had to leave the plane at Brisbane. In any case, Lyon repeated the Australian welcomes were for the Aussies; that’s why he and Warner had left the plane as soon as possible.

Group photo in Fiji, drinking Carver with a local Chieftain. It looks like Lyons is interested in something stronger.

Group photo in Fiji, drinking Carver with a local Chieftain. It looks like Lyons is interested in something stronger.

Smithy and Ulm would like the Press to come to their room.

Luncheon held for the trans-Pacific airmen by the ‘Sun’ newspaper, at Hotel Australia, June 1928. Austin Byrne collection, National Museum of Australia.

Luncheon held for the trans-Pacific airmen by the ‘Sun’ newspaper, at Hotel Australia, June 1928. Austin Byrne collection, National Museum of Australia.

Ellison didn’t lose any time, he had a big, breaking story:

I immediately left Lyon and got in touch with a chap who was acting as a secretary to Smithy and Ulm; as a representative of the Sydney Daily Guardian, I said, I wanted to see Smithy and Ulm on an urgent matter. Couldn’t be done they were getting ready for the official dinner. Then, I said, would he put these questions to them: Were Lyon and Warner going on the Southern Cross to Sydney? If not, why? Also would he tell Smithy and Ulm that if the two Americans were out, the Guardian would charter a plane and fly them to Sydney to arrive there at the same time as the Southern Cross. I would wait half and hour, I said, and then if I could not get an interview with Lyon, and then get on with the plane charter. Incidentally, I wasn’t empowered to undertake this charter, but I felt sure the Guardian would have approved.

Source: Discovering our ANZACS online https://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/browse/gallery/13667

Source: Discovering our ANZACS online https://discoveringanzacs.naa.gov.au/browse/gallery/13667

Ten minutes later the secretary came back to the lounge – several other reporters had arrived – and Smithy and Ulm would like the Press to come to their room. There Ulm was the spokesman. He said there had seemed to be a story around that the two Americans were being left in Brisbane. Not so, he declared; they were coming to Sydney on the Southern Cross. They did.

28/07/1928. Sydney arrival

Top: Aerial view of the ‘Southern Cross’ being surrounded by a police guard on arrival at Mascot. Below: View of a section of the crowd at Mascot, with Warner’s hand-written notation – ‘200,000 people’. Austin Byrne andJames Warner collection, National Museum of Australia.

Top: Aerial view of the ‘Southern Cross’ being surrounded by a police guard on arrival at Mascot. Below: View of a section of the crowd at Mascot, with Warner’s hand-written notation – ‘200,000 people’. Austin Byrne andJames Warner collection, National Museum of Australia.

So the Americans made it to Sydney. Ulm made Lyons and Warner sign contracts, as Lyons mentioned. In Ulm’s mind, he and Smithy had come up with the idea and largely made it happen against the odds, so only they could lay claim to any fame and fortune that followed. There is truth to this. He and Smithy spent up to a year in the US getting the venture together, driven by Ulm’s organisational skills.

Ironically, the venture relied on generous support from an American multi-millionaire who bought and donated the aircraft, and would not have been a success without Lyons and Warner. However Ulm felt they had no right to participate in the celebrations after the Fiji leg, as he regarded them as contractors. Kingsford Smith publicly praised and acknowledged the importance of Southern Cross crew, but went along with this decision.

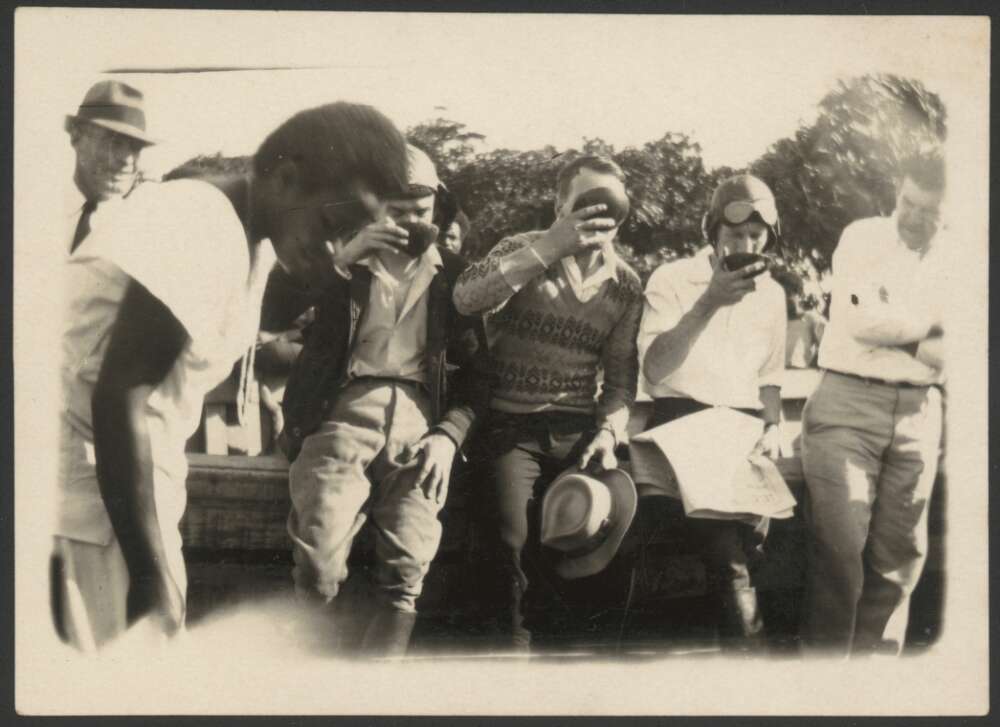

The exhaustion of the last leg, social schedule, including drinks stronger than carver, show on the faces of the four airmen. It was at this time that tensions between Lyon and Ulm. Source: Charles Ulm national aviation collection

The exhaustion of the last leg, social schedule, including drinks stronger than carver, show on the faces of the four airmen. It was at this time that tensions between Lyon and Ulm. Source: Charles Ulm national aviation collection

Keith Anderson Memorial Rawson Park, Mosman. Photo by author Feb 2020

There was one person however who had some claim to compensation. Fellow aviator Keith Anderson, a major contributor to the project’s start-up, took legal action against Smithy and Ulm after he became aware he would be left out of any share.

This bitter split between an old friend and colleague haunted Smithy, normally a man of few regrets. Ellison eported on this story as it unfolded. What hurt Smithy were accusations that he and Ulm stage-managed a rescue for publicity, resulting in tragedy, despite combined, desperate efforts to find Anderson and his co-pilot.4

‘Kookaburra’ lost in the Tanami desert

‘Kookaburra’ lost in the Tanami desert

…a happy burden of debt upon every Australian

For his part, Ellison’s efforts were pivotal. The Americans joined the national celebration. Over time their names were inevitably forgotten. As a writer for the Sydney Morning Herald waxed lyric, in summary:

…the fact remains that these four brave men and their magnificent machine have done much for the

science of aviation and for Its practical advancement, in the years to come, when feats like this are the commonplace of the age, history will record, and all men will acknowledge, the great effect upon world communication and transport for which these pioneers of trans-Pacific flight were responsible. For they have proved that with careful organisation and finely applied skill and stout hearts the widest ocean may be traversed and the fury of Its storms outstayed and conquered. It was a fitting thing that two Australians should be associated in this historic flight with two Americans.

The services of Mr. Lyon,the navigator of the Southern Cross, and of Mr. Warner, her wireless operator, have laid a happy burden of debt upon every Australian. And we would be ungenerous Indeed not to acknowledge it gladly and gratefully. It is good to know that the deeds of Kingsford Smith and Ulm are to be recognised by their country in appropriate fashion, and we trust that the welcome we accord to their brave companions will show them, too, how greatly we appreciate the work they did so well.

Left to right, Warner (ground), Lyon, Ulm and Kingsford Smith at the podium amongst the crowd at Mascot. Austin Byrne collection, National Museum of Australia.

Left to right, Warner (ground), Lyon, Ulm and Kingsford Smith at the podium amongst the crowd at Mascot. Austin Byrne collection, National Museum of Australia.

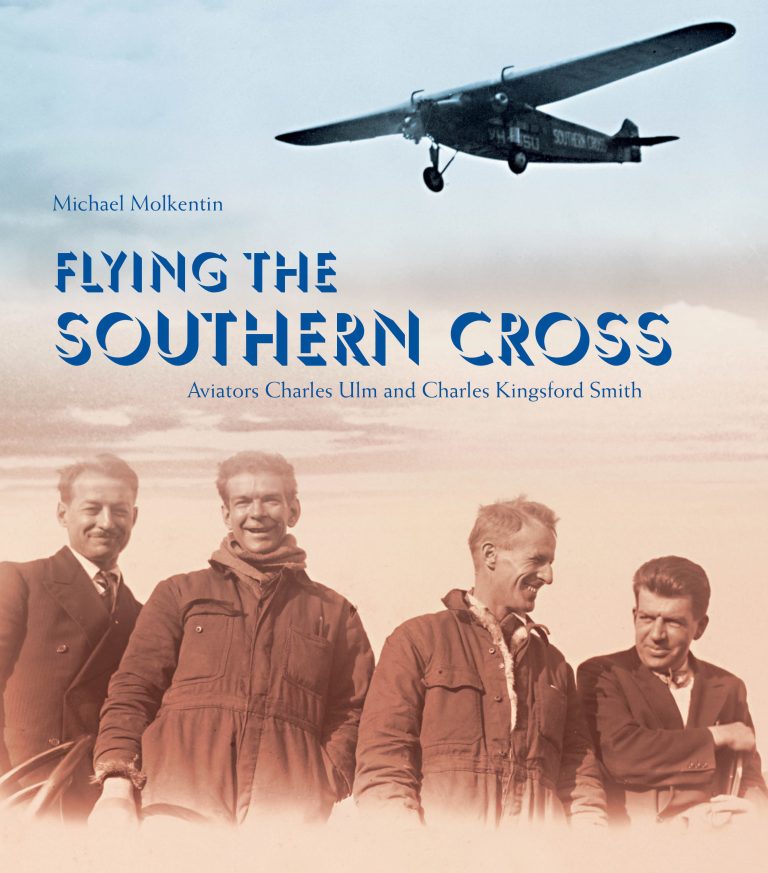

After writing this I (finally!) watched Michael Molkentin’s talk with John Ulm. Much of what I found in researching this story is mentioned. However, two things are worth noting here. John, working for Qantas, organised for Warner and Lyons to be brought out to Australia for the 30th-anniversary unveiling of the Southern Cross memorial, Brisbane, and medal ceremony. He even made a film featuring them. They were asked about leaving the plane early. Their response wasn’t that they’d been kicked out. It was more that they’d just had enough, and wanted to get away quickly as possible. And so, debarring any polite glossing-over of the past on their part, this is what happened. What Lyons said to Ellison rang true in either case Their contract ended with the arrival in Brisbane and as far as they knew the Australian welcomes were for the Aussies; that’s why he and Warner had left the plane as soon as possible.

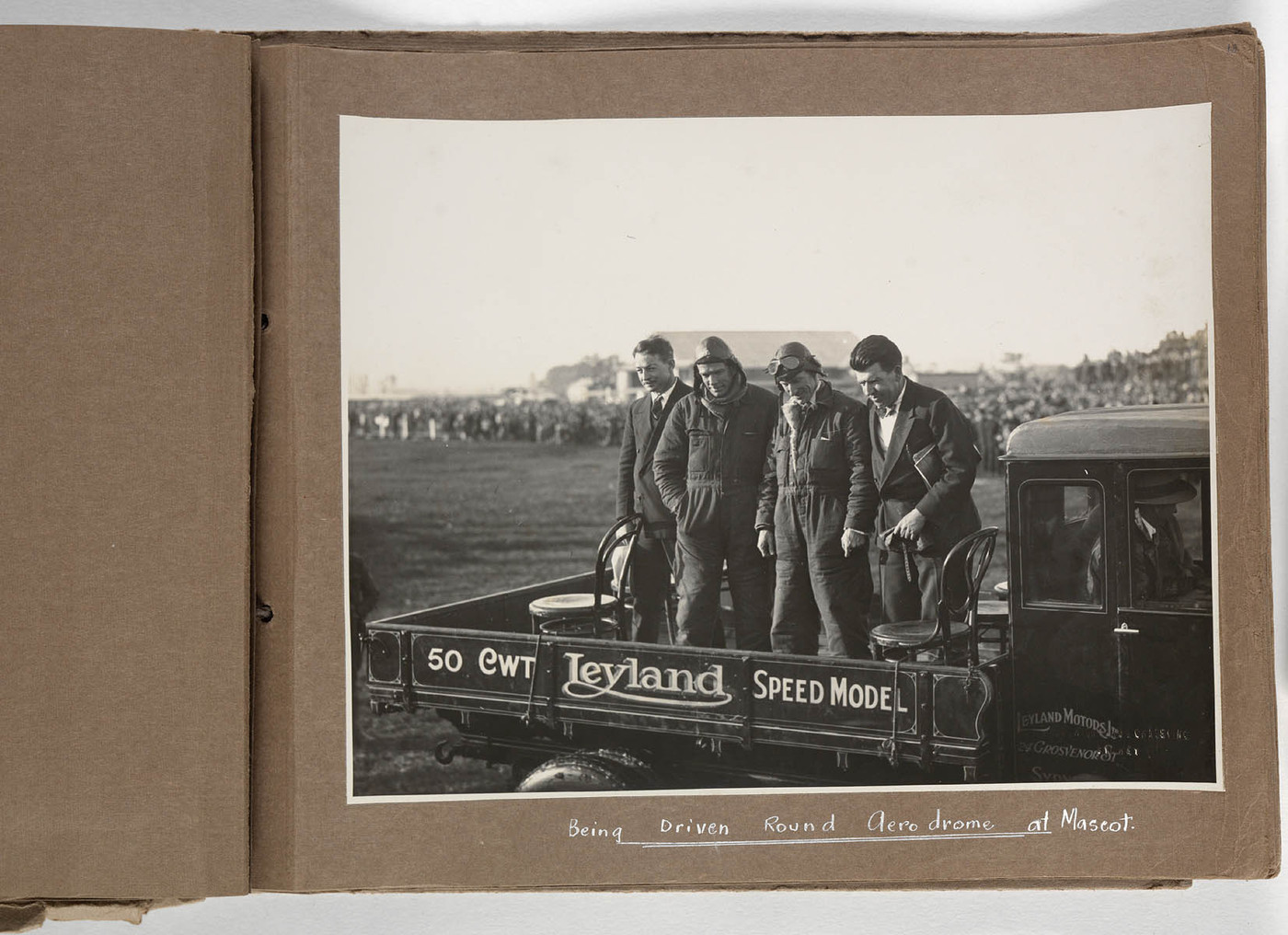

Charles Ulm – photographs and albums, 1928-1934 Source SLNSW PXD 921 MP 98

Charles Ulm – photographs and albums, 1928-1934 Source SLNSW PXD 921 MP 98

Follow the Smithy and Ulm Story:

Recommended reading

War Service and beyond…

…and the Norman Ellison Story:

- “ ‘I’m rambling now but I enjoy doing it!’: Rodney Ellison’s Mosman Memories

Also related:

Also : Digitised logbook made by Charles Ulm during the flight is held by the National Library

Footnotes

1 AIRMEN MOBBED. (1928, June 11). The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), p. 13. Retrieved July 1, 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21295459 . The Sun had signed an exclusive rights deal with Ulm to updates as the Southern Cross crossed the Pacific. Readers and households hung on every exciting detail of the airmen’s progress.

2 Rodney Ellison’s memories have been digitised on Trace: http://images.mosman.nsw.gov.au/?code=NDk1MQ==%3D

3 All quotes from Flying Matilda : early days in Australian aviation Sydney : Angus & Robertson, 1961. by Norman Ellison

4 see De Broglio, B Keith Anderson memorial http://mosman1914-1918.net/project/blog/keith-anderson-memorial

Next record flight: trans-Tasman crossing to New Zealand and back…

Next record flight: trans-Tasman crossing to New Zealand and back…