On the blog we’ve looked at the main WWI memorials in Mosman but there’s another unique landmark with a strong connection to the First World War. It remembers the only man buried in Mosman.

Gavin Souter tells the story best in Mosman : A History and it begins with the Presbyterian church on Belmont Road, now known as Scots Kirk, and its second Minister.

Reverend Donald Peter Macdonald was ‘a man of wide interests’ with “the gift of creating great occasions when the people thronged to hear him.”1 He was later to enter political life as Mosman’s member of the State Legislative Assembly. Macdonald served as padre with the 2nd Division Artillery in France from 1917 and a fine portrait photograph from this period hangs in a vestibule of the church.

One of Macdonald’s most notable undertakings was literally just that, for it was a funeral which evoked the most intense communal emotion ever displayed in Mosman. The depth of public feeling aroused by the death of Flight-Lieutenant Keith Anderson in 1928 is something not easily understood by a later generation. It had to do with the pride so widely taken in the international achievements of Australian aviators, but that alone does not fully explain the extent to which Anderson’s tragic death was memorialised. In D.P. Macdonald’s mind the Anderson Memorial may also have been inspired by the Great War and by Mosman’s Scottish heritage.

Souter, Gavin 1994, Mosman : a history, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic

Keith Vincent Anderson

Photograph of Keith Anderson, the late pilot of Westland Wigeon aircraft ‘Kookaburra’ – National Museum Australia, 1985.0027.0001.002

War Service

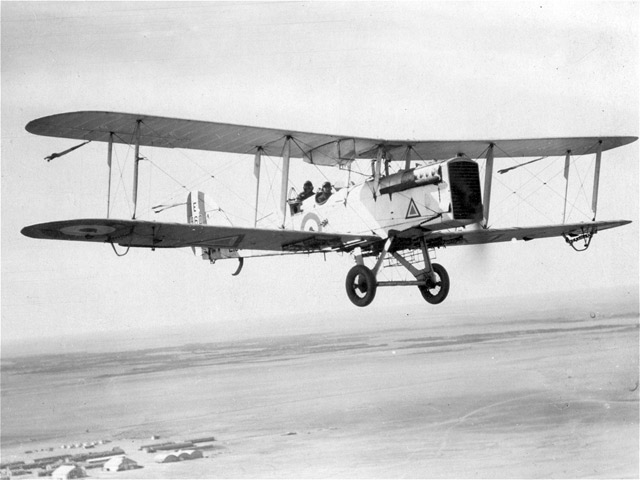

The airman was educated at South African College and when he was 18 years old there was, in South Africa, Major Alastair Miller, whose mission was to enrol recruits for the Royal Flying Corps, the Great War having been in progress nearly two years at the time. In the enrolment of cadets Keith Anderson was one of the first chosen, and he removed to England to continue his training and securing his commission, was in France before the end of 1918. During the war he handled several types of aircraft, among them the Maurice Farman, Avro, Sopwith “Pup“ and “Camel,” De Havilland, 6, 9, and 9A, and the BE2 2E.

Nine Captures

Although he was not actually wounded Anderson suffered from shell-shock. He had many thrilling skirmishes with enemy aircraft, but a natural modesty made him disinclined to discuss his experiences in France. However, it is known that he was responsible for the downfall of no less than nine German machines, but army practice demands that corroboration shall be forth coming of victims brought to earth, and although five of Keith’s were identified it was impossible to confirm the others, otherwise he would have qualified for the decoration awarded to the allied airmen responsible for the destruction of six German ‘planes.

1929 ‘KEITH ANDERSON’S CAREER.’, Western Argus (Kalgoorlie, WA : 1916 – 1938), 23 April, p. 34, viewed 24 January, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article34483913

Airco D.H.9A. Source: Royal Air Force

Flight-Lieutenant Keith Anderson’s service record suggests2 he saw action between Cambrai and Saint-Quentin where low level strafing was carried out by 73 Squadron. In 1918 he was with the Independent Force, RAF who undertook long range bombing missions against railways, aerodromes and other industrial targets in France and Germany.

[A]fter the armistice he returned to South Africa, eventually coming back to Australia in 1921… He joined the Westralian Airways Ltd, in 1922, and for two years was pilot on their North-west air mail route.

1929 ‘NOTABLE CAREER.’, The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), 22 April, p. 15, viewed 25 January, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article21397965

Smithy & the Southern Cross

Sir Charles Kingsford Smith stands on the wing of a Bristol aircraft with, left to right: Bob Hitchcock, Keith Anderson and Charlie Ulm standing in front, c. 1928. Source: State Library of South Australia

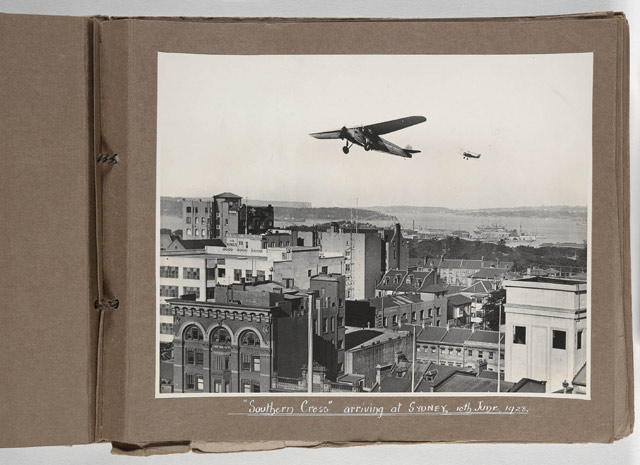

That famous first flight across the Pacific was initially a joint venture between Anderson, his longtime friend and fellow WWI pilot Charles Kingsford Smith, and Charles Ulm, a Mosman boy. The story is too long to tell here but Anderson and air mechanic Bob Hitchcock were replaced by two Americans at the eleventh hour, and the acclaim that greeted the successful crew of the Southern Cross led to rancour and a court case. Anderson lost, but Kingsford Smith made an out-of-court settlement of 1,000 pounds. In a tragic irony, Anderson used the money to buy the Kookaburra.

“Southern Cross” arriving at SYDNEY, 10th June, 1928. Charles Ulm – photographs and albums, 1928-1934, State Library of NSW

Following the Pacific flight they [Anderson and Hitchcock] had unsuccessfully attempted to sue for shares in the venture’s profits. Remarkably, the whole episode had not completely soured the relationship and when Southern Cross went missing, Anderson and Hitchcock agreed to join the search.

Molkentin, Michael 2012, Flying the Southern Cross : aviators Charles Ulm and Charles Kingsford Smith, National Library of Australia, Canberra

Tragedy in the Tanami Desert

Flying over the crashed Kookaburra, 1929. Source: State Library of Western Australia

Early in April, 1929, Keith Anderson in his ‘plane the “Kookaburra” with Mechanic Hitchcock hurriedly left Sydney to the rescue of fellow airmen, then missing in North West Australia.

When over the treacherous desert country in Central Australia (Lat. 170° 56’, Long. 132° 18’)3 the engine failed and the “Kookaburra” was forced to land there, never to rise. After many anxious days the ‘plane and the bodies of these gallant men were found by Pilot Lester Brain, A.F.C, of Quantas, Queensland, and their brave story was written there by Keith Anderson on the tail of his machine.

The remains of these noble flying men were recovered for burial from the desert by Flight-Lieutenant Eaton and other brave men, who endured great hardships in rhe undertaking.

Mechanic Hitchcock’s remains were taken to Perth, W.A., for burial there, and Lieutenant Anderson’s last resting place will be on beautiful George’s Heights, a site granted by the Council of the Municipality of Mosman.

In Memoriam, Flight-Lieut. Keith Anderson – Mosman Presbyterian Church, 6 July 1929

Burial at Mosman — why?

Again we turn to Mosman’s historian, Gavin Souter:

By the time Anderson’s body reached Sydney on 29 June the general desire – endorsed by his fiancée, Miss L. M. Hilliard, and her parents, all of whom lived in Mosman Street – was that he should be buried in Rawson Park, the most majestic site in all of Sydney, overlooking Georges Heights, Middle Head, Middle Harbour, North Harbour and Port Jackson. The idea was D.P. Macdonald’s. Whether the minister had known Anderson or his fiancée personally is uncertain, but once the thought of a grave and memorial in Rawson Park had occurred to him he urged it upon the Council with all his accustomed vigour.

The first mention in Council records is a Mayoral Minute from Alderman A. Buckle to the Council Meeting of 9 July 1928:

Burial of the body of the late Keith Anderson. Dated 3rd. July, 1929. In this connection the Mayor was approached relative to a site being made available for this burial in a portion of Rawson Park. The Mayor consulted all the Aldermen immediately available and it was decided that the site be provided subject to necessary arrangements being made with the various authorities. Subsequent to an interview which the Mayor and Town Clerk had with the Minister for Lands, the matter was referred to Cabinet which decided not to offer any legal objections, in view of the representations put forward on behalf of this Council. The selected site is outside the park enclosure, on high unenclosed ground which is visible from a very wide area. The burial which has been arranged by the Commonwealth Government is to take place on Saturday morning next.

Minutes of the Ordinary Meeting of the Council of the Municipality of Mosman held in the Council Chamber, Town Hall, Mosman on Tuesday, 9th July, 1929 at 7.45pm

Mourning at Mosman

Funeral [Military Road, Mosman?], 1929. Source: State Library of Western Australia

In a resting-place that is befitting a national hero – on high ground between Sydney Harbour and Middle Harbour, facing the sunrise – the body of Flight-Lieutenant Keith Anderson was laid away on Saturday morning.

As the coffin was borne from the Mosman Presbyterian Church to Rawson Park the nation paid homage to the memory of a brave man. Governments and public bodies, war establishments, and the Institutions of peace were represented officially. Soldiers walked with arms reversed before the gun-carriage which bore the airman’s body, blue-clad mechanics of the Air Force marched on either side, a Minister of the Commonwealth walked bare-headed among the chief mourners, aeroplanes swooping down to near the level of the tree tops, dropped wreaths and flowers.

But the most remarkable tribute, because it was entirely spontaneous, came from the people. They gathered in thousands in the quiet suburban street before the church, and in thousands followed the cortege over the rough track to the high, open space where the grave had been dug. There was no demonstration, no talking. They came, simply and quietly, to say farewell to one of those young Australians who have made Australian aviation famous for all time. In honouring his memory the people paid honour to the courage and the ability of the whole splendid band of Australian aviators.

1929 ‘LAST TRIBUTE TO KEITH ANDERSON.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 8 July, p. 10, viewed 25 January, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16564473

The Airmen’s Tribute

As the cortege proceeded at a slow pace to Rawson Park three squadrons of aeroplanes and two or three single machines (thirteen in all) manoeuvred overhead, and dropped wreaths and flowers. The five Moths, which led, flew in the form of a cross. The squadrons kept fairly high, and made wide circles while the funeral procession moved slowly through the crowded streets, but individual machines continually came down close overhead They had all been flying over Mosman for more than an hour by the time the coffin reached Rawson Park, so, with a final “dip,” as a mark of respect to their lost comrade, all except one flew off towards Mascot. That one, a Westland III monoplane, continued to fly backwards and forwards above the park, and just before the coffin was lowered, the pilot came very low and dropped his tribute, a wreath of red flowers and green leaves, almost on top of the coffin. It was a little incident that seemed, somehow, to typify the wonderful brotherhood of the air.

1929 ‘LAST TRIBUTE TO KEITH ANDERSON.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 8 July, p. 10, viewed 25 January, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16564473

At graveside [Rev. Macdonald in uniform?], 1929. Source: State Library of Western Australia

In a grave that was a bower of gum leaves, ferns, violets, and moss, the remains of Lieut. Anderson were laid to rest on a rocky elope of George’s Heights. While fourteen planes droned overhead 6000 people heard the Rev. D. P. MacDonald read the burial service.

1929 ‘KEITH ANDERSON’S FUNERAL.’, Sunday Times (Perth, WA : 1902 – 1954), 7 July, p. 1 Section: First Section, viewed 25 January, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article58422857

A Memorial Erected

One year later, a monument was raised above his grave.

Monument, 1930. Source: State Library of Western Australia

The cross recalled the many monuments that had been erected for the First World War fallen.

“I like to think of him welcomed by the great company of his former comrades whose names are recorded at Arras”

— Governor of New South Wales, Sir Philip Game1930 ‘LATE KEITH ANDERSON.’, The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), 29 July, p. 11, viewed 25 January, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article29807229

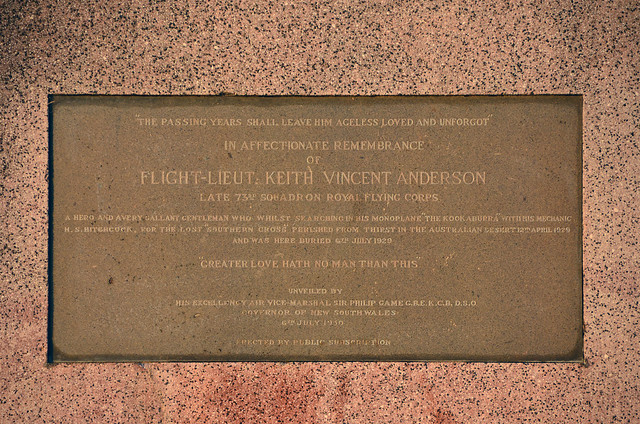

The plaque still stands and tells the story:

“The passing years shall leave him ageless loved and unforgot” / In affectionate remembrance of Flight-Lieut Keith Vincent Anderson, late 73rd Squadron Royal Flying Corps / A hero and a very gallant gentleman who whilst searching in his monoplane “The Kookaburra” with his mechanic H S Hitchcock for the lost “Southern Cross” perished from thirst in the Australian desert 12th April 1929 and was here buried 6th July 1929 / “Greater love hath no man than this” / Unveiled by His Excellency Air Vice-Marshall Sir Philip Game G.B.E. K.C.B. D.S.O. Governor of New South Wales 6 July, 1930 / Erected by public subscription.

And spare a thought for the Minister whose energy made its mark on Rawson Park.

Public subscription brought in £500, and a Celtic cross of the kind found in Scottish graveyards was designed by the architect and former AIF divisional commander, Sir Charles Rosenthal. The finished cross […] was made of polished pink granite aggregate, 16 feet high, with a laurel wreath in the centre and ivy leaves down the shaft. If D.P. Macdonald did not actually inspire the choice of cross, he would certainly have welcomed it…

Souter, Gavin 1994, Mosman : a history, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic

Sunrise at Rawson Park – more photos on Flickr

Footnotes

1 Mackillop, John Crawshay 1973, Scots Kirk, Mosman : a history of Presbyterianism from 1890, Scots Kirk, Mosman, N.S.W

2 RFC/RAF service chronology, based primarily on the service record:

| 1917-04-11 | Cadet, RFC |

| 1917-04-11 | Recruits Depot |

| 1917-05-18 | 2 Officer Cadet Wing |

| 1917-07-27 | 2 School of Military Aeronautics |

| 1917-08-30 | T2/Lt. Temporary [?] 2nd Lieutenant, Probationary General List – London Gazette 18.9.1917 |

| 1917-09-03 | 4 Training Squadron |

| 1917-09-28 | 89 Squadron – on Appt. Flying Officer Branch [to which aircrew were appointed upon graduation] |

| 1917-12-14 | T2/Lt. Flying Officer, confirmed rank – London Gazette 24.1.18 (see above) |

| 1918-01-30 | 2 (Auxiliary) School of Aerial Gunnery |

| 1918-02-24 | 73 Squadron |

| 1918-03-17 | Entry in The Camel File by Ray Sturtivant for Camel B4605 of No 73 Sqn RFC, which Anderson was flying when it was wrecked and abandoned on 17 March 1918 |

| 1918-04-01 | promoted Lieutenant |

| 1918-04-06 | Home Establishment |

| 1918-04-19 | Headquarters Southern Training Brigade |

| 1918-06-06 | 14 Training Depot Station |

| 1918-06-23 | C.D. [G.D.?] Pool – N.E. Area for disposal in 18 Group |

| 1918-08-10 | 1 School of Aerial Fighting |

| 1918-10-21 | 1 School of Navigation & Bomb Dropping |

| 1918-10-23 | Independent Force, RAF – N.W. Area for disposal – as DH9 pilot |

| 1918-11-01 | 42nd Stationary Hospital, admitted 1918-10-31 |

| 1918-12-05 | 20 Group for disposal – as Camel Pilot |

| 1918-12-09 | 32 Training Depot Station |

| 1919-01-09 | 26 Training Depot Station |

| 1919-02-15 | 2 Training Depot Station |

| 1919-05-05 | Blandford Repat Camp |

| 1919-07-13 | Lt. ALBD [BD may be to do with Bomb Dropping?] DH.9a, R.S.[?] Camel |

| 1919-10-06 | Transferred to Unemployed List |

3 The 1929 In Memoriam gives the latitude an extraneous ‘0’, perhaps a typesetter’s error. The coordinates 17° 56’ South, 132° 18’ East place the crash site near Wave Hill station in the Tanami Desert.

Acknowledgements

Errol Martyn, Gareth (Dolphin) and Mick Davis, Great War Forum, for help with Anderson’s RFC/RAF service record. Sources included RAF Flying Training and Support Units since 1912 by Ray Sturtivant, rafweb.org and ww1aero.org.au.

Bill (WhiteStarLine), Great War Forum, for debugging crash site coordinates.

Gabrielle, a young student from the Blue Mountains, for the wonderful blog keithandersonaviator.blogspot.com.au