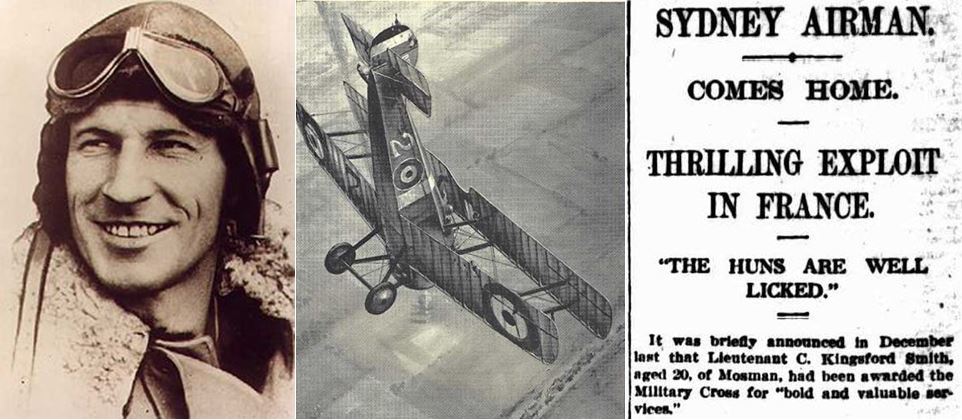

Charles Kingsford Smith’s flying career was forged in the fires of adversity. In his autobiography My flying life he recalled:

Sometimes our squadrons would sweep the sky in bands 20 strong, looking for trouble in the shape of Hun machines, and generally finding it. We flew low over enemy aerodromes and trenches, ground strafing and attacking anything in sight with our drums of Lewis fire. At other times we flew high, waiting At 15,000 ft. to pounce on our enemies, and there were exciting and adventurous occasions when we deliberately cultivated a spinning nose dive in an effort to avoid attack, or with nonchalant abandon rolled carefree.

…We did the job to the best of our ability in what seemed to be the craziest old antiquarian contraptions imaginable- the machines of the Royal Flying Corps… And we were up against an enemy that was ahead of us in aircraft design, and certainly not our inferiors in courage, élan and dash.

The Terror of Mosman

Charles’ risk-taking behaviour started early in life. Catherine, his mother, recalled how ‘Chilla’ (his family nickname):

…delighted in living dangerously. Riding his bicycle at frantic speed on the suburban footpaths, careering down steep hills, hands off the handlebars…1

In his late teens to satisfy his passion for noise and power:

he acquired a second-hand motorbike on which his recklessness soon earned him the nickname ‘ the ‘Terror of Mosman’2, and numerous police warnings for speeding. Neighbours predicted that he would break his neck. But it was the bike he wrecked, smashing it one day through the wall of a dairy and ending up in a heap of bottles and confectionery.3

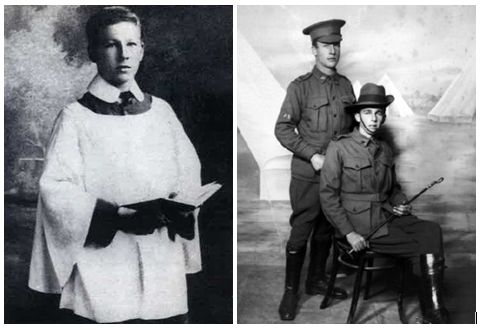

Left: Chilla as a St Andrews boy soprano choristor. Right: Sapper Charles Edward Kingsford Smith of Neutral Bay (left) and friend after enlisting in the Australian Army. Picture: Australian War DA08453

Left: Chilla as a St Andrews boy soprano choristor. Right: Sapper Charles Edward Kingsford Smith of Neutral Bay (left) and friend after enlisting in the Australian Army. Picture: Australian War DA08453

Like many young men at the time, Chilla found the Empire’s call irresistible. On his 18th birthday he enlisted with the AIF, transferred to the 4th Light Horse, and was shipped off to Gallipoli via Egypt.

In a letter home Smithy wrote home about the risks of his job running messages:

Snipers are pretty bad at the foot of our gully and get our chaps fairly often. One has to do a sprint or have a bullet after him.4

A holed cap was sent as evidence of a close call5. His family must have felt both relieved and anxious receiving this souvenir in the post.

Out of the Frying Pan…

After surviving Gallipoli, Chilla saw action in France, as a dispatch rider.6 Once again, he had close calls, surviving near-misses from German shells.7

Charles’ letters home were upbeat. But after seeing the front-line first hand, he confessed:

Some of the sights out there are really sickening.8

A.I.F. causalities after Western Front Battle: Photograph by Frank Hurley

Due to a pilot shortage, the opportunity arose to apply for the Royal Flying Corps. Sgt. Kingsford Smith jumped at the chance. After passing the vetting process,9 training, examinations, and instruction on a Maurice Farmans, Smithy flew solo:

I am some pilot now, and can land and stunt and do anything in the aerobatics line except loop. I’d try that if these machines would do it. But they tell me that a wing is liable to go off with the strain.

The usual B.S. as these types could not do advanced aerobatics. In fact, four days later he misjudged a landing and wrote:

The machine was wrecked, but I, being marvelously lucky, only got shaken and a bit bruised10

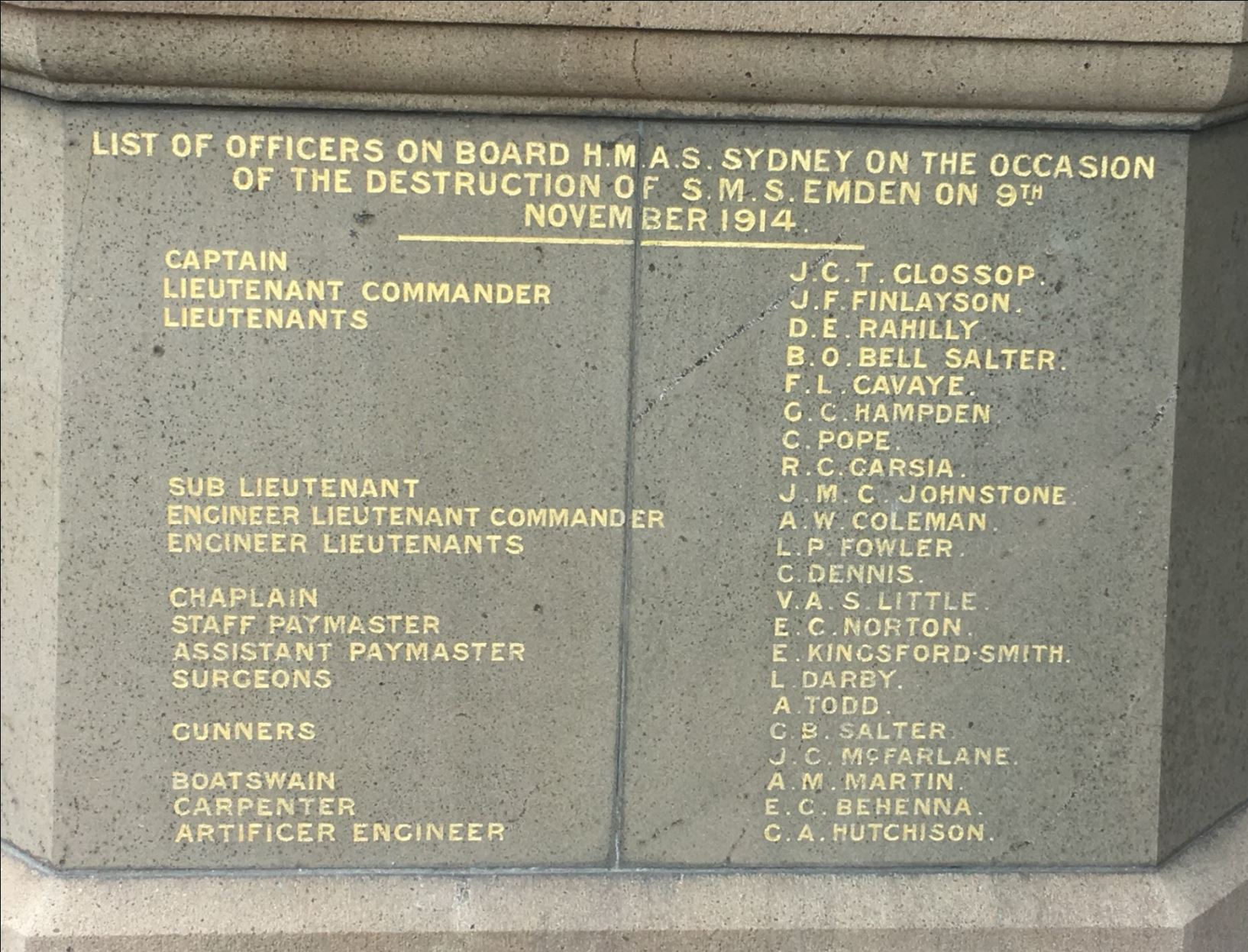

One of the highlights of this period in Smithy’s life was his meeting, for the first time in years, with his brother Eric, in age his nearest brother [onboard HMAS Sydney]

Eric had been a paymaster on the Sydney during her famous encounter with the SMS Emden (His name appears at the Emden gun memorial in Hyde Park.)11

According to Smithy historian and Mosman resident Norman Ellison:

On leave from Denham, R.F.C Cadet Charles went to the Firth of Forth to see Paymaster Leiutenant Eric Kingsford Smith, whose ship, Sydney, was with the Grand Fleet. It was an enthusiastically happy reunion, and the visitor was overjoyed when he was allowed to stay on the cruiser for a few days. “I’ve got a cabin to myself, a servant and all,” he boasted when he wrote to his parents. He proved a welcome guest in the mess, because at the time he was the only member who could play the piano – he was self-taught -and he could sing many a rollicking soldier song. He was gleefully impressed by the salutes he got ashore; some privates were so zealous as to accord commissioned status to an R.F.C. cadet wearing a Burberry.12

…into the fire.

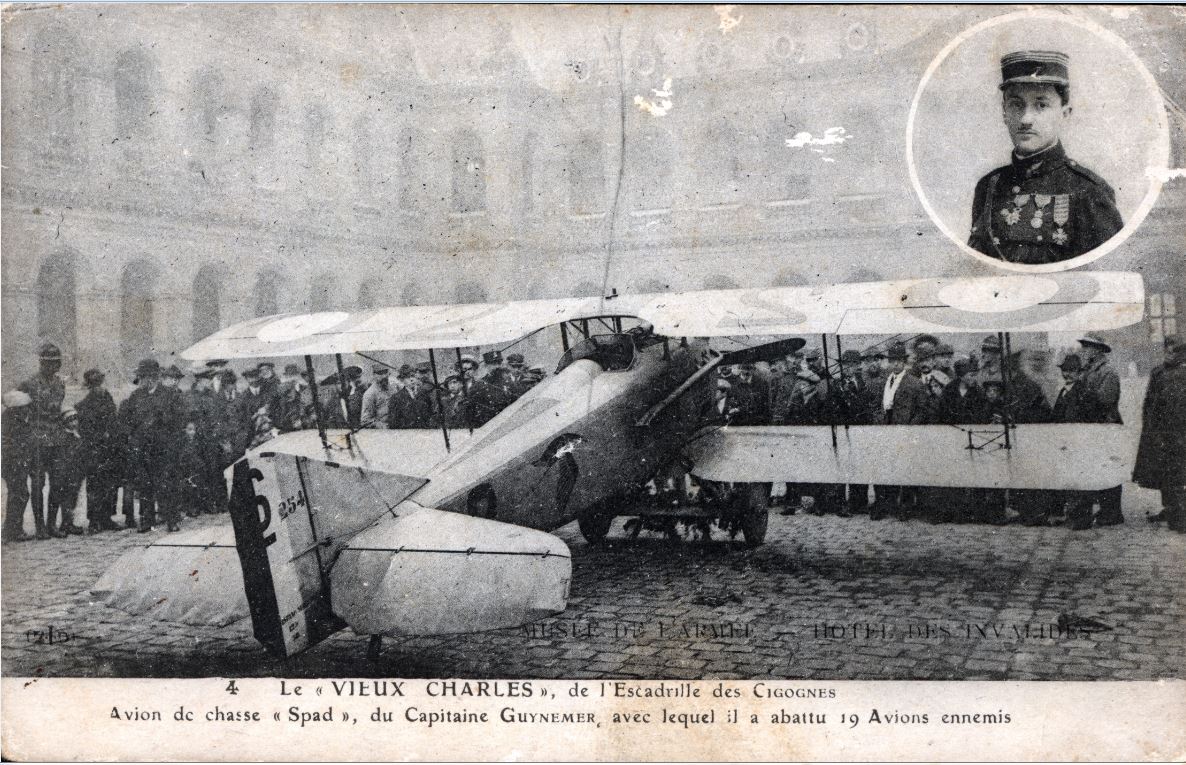

Smithy got his ‘wings’ after 30hrs in the French designed SPAD13

The SPAD was flown by British, American and French aces. Above: Postcard ‘“SPAD”, du Captaine Guynemer’, Source: Barry O’Keefe Library ‘Trace’ digital archive. This item belonged to Wilfred Joseph Allan Allsop.

The SPAD was flown by British, American and French aces. Above: Postcard ‘“SPAD”, du Captaine Guynemer’, Source: Barry O’Keefe Library ‘Trace’ digital archive. This item belonged to Wilfred Joseph Allan Allsop.

Smithy’s initial assessment of his new ‘bus’14 was favourable:

The Spads are great machines. They fly at 140 m.p.h., Some going, eh?

Despite only having a single machine gun it was fairly maneuverable, dived and climbed well (up to to 20,000 ft.) They could also take a bit of punishment, as he was later to find out.

Smithy was posted to 23 Squadron based at La Louvie aerodrome, Pas de Calais. His first combat patrols started in July 1917. On the 14th he wrote home:

Just a short note this time to let you know I’m alright, etc. I got my 1st Hun this morning. Eight of us attacked about 20 Huns and had the dickens of a fight. One…dived across in front of me. So I got my sight on and let him have about 50 rounds before he could get out of the way. I had the satisfaction of seeing him chuck up his arms and fall back. The machine glided on for a while and then nose-dived straight for the ground…I had bad luck after bagging my first bird. My gun jammed and I had to leave the scrap and tootle off home.

Yesterday we had another scrap and I had a rather narrow squeak. My gun jammed early in the fight and I put my nose home to get it fixed, when 3 spare Huns sat on my tail and kept there all the way…[they] were firing all the way down. I landed with holes all over the machine and one burst of a dozen alongside my ear. I was rather badly scared…15

On landing he found a bullet hole in the collar his tunic. Another souvenir, another close call.

Filled with an unearthly joy

‘Balloon busting’ was important work carried out by Smithy’s squadron. ‘OB’s’ (Observation Ballons) were usually well defended so counted as a ‘kill’ if shot down.

23 Squadron was also tasked with attacking ground targets, if the opportunity presented itself.

Ending one patrol, Smithy looked down to the ground far below. He saw a field-grey line, snaking through the obliterated landscape. German troops en route to the front, resting in one mass of humanity. He broke formation and swooped into a screaming dive:

Over my sights, I could see men moving down the road, but there were too many of them to move quickly. I pressed the trigger. Tracer bullets zipped along the road and I saw men falling, and hundreds of them scrambling to get out of the way. I was filled with an unearthly joy.

Smithy shouted over the roar of engine noise as he lined up another pass. It was like shooting Feldgrau mice in a barrel. He couldn’t miss:

I kept my finger pressed hard on the trigger. Then I turned and roared back with my machine gun spitting death. I saw dozens of men bowled over…16

After his ammunition was spent on the infantry below, Smithy put his SPAD into a climb. Cracks of rifle shots followed the aircraft. He landed back at the aerodrome, cut the ignition, and climbed out of the cockpit.

After the noise of the engine and the gun, everything, all of a sudden, was quiet. I could hear birds whistling and men laughing and talking. Contact with these realities suddenly made men realise the horror of the thing that I had done. I leaned against the fuselage and vomited. I was twenty years old, I had just killed men and I hadn’t the faintest idea why. For those few minutes I had gone completely insane. Now I felt utterly miserable and hated my weakness for doing what I did.17

Photograph of La Lovie Chateau or Poperinghe aerodrome in 1915 [Authors note: the picture is blurry but the aircraft appear to be of different types including a Sopwith Dolphin (?) therefore the photograph must be later than 1915]

Photograph of La Lovie Chateau or Poperinghe aerodrome in 1915 [Authors note: the picture is blurry but the aircraft appear to be of different types including a Sopwith Dolphin (?) therefore the photograph must be later than 1915]

In a letter home he put on a brave face, highlighting his accomplishments:

Got another Hun this morning. We were out at 4:30 am looking for something to strafe. I saw this chap flying very low just below the Hun trenches. So I dived and fired at him, driving him back into Hunland and lower all the time, until he hit the ground and turned right over. So I came at him again and had the satisfaction of seeing him catch fire. Later on I killed a lot of Hun troops and set fire to some wooden huts in Hunland. So you see I had a good morning. I am mentioned in the commander’s report as having done bold and valuable service.18

However, his bravado and devil-may-care attitude showed signs of cracking. He later wrote:

It will soon be winter now, and we RFC people will get a spell - thanks goodness. We are doing frightful quantities of work now and couldn’t keep it up indefinitely, or our nerves would go to pieces.19

When Smithy first arrived at La Lovie aerodrome20 he noticed:

…many vacant places at the dining table and in the sleeping quarters. And the survivors, all youngsters like me…[had]…the faces of much older men.21

Smithy probably felt older himself after just six weeks. Only three of the sixteen pilots he’d graduated with were still flying22. Every combat patrol flown, increased the likelihood of leaving his chair empty.

The hunter becomes prey

Heading home from a regular patrol on the 14th of August, Smithy noticed something. An aeroplane from his flight broke formation. Thinking the other pilot had spotted an enemy aircraft, he followed. Smithy flew into black bursts of AA fire, then after losing his wing-mate, turned back. Shortly the trap was sprung.

On the 29th, he recalled what happened next:

A German fighter, stalking him in clouds above, had pounced whilst he was diving on the two seater. The Jasta scout swooped into Smithy’s blind spot, with perfect timing. Smithy’s SPAD was sprayed with a burst from 2 Spandau machine guns at point blank range. Smithy’s adversary, Obltn. Wilhelm Reinhard, followed the stricken SPAD down, to issue the coup-de-grace, which, thank goodness, he failed to do…I spotted two Hun two-seaters away below me…I proceeded to turn the old bus on her nose and dived…I sort of recollect a fearful clatter in my ear and a horrid bash on my foot, which made me think the whole leg had gone. Then I fainted. It turned out the bullet had busted numbers of nerves, and the shock sent me off.

When I came to -30 or 40 seconds later, or whenever it was - I was spinning, nose first, down to Hunland. The little holes and chips of wood, etc., were suddenly appearing all around me where the Hun’s bullets were chewing things up. I tried to turn round to scrap but my whole left leg was paralysed, and I could only fly ahead as fast and as steadily as I could for our lines, and pray that he wasn’t a very good shot.23

Albatros D.V of Obltn. Wilhelm Reinhard, Jasta 11, 1917/18; The ‘Hun’ thought to be responsible for shooting Smithy down.24

The deadly chase presumably lasted all the way to the British lines, but Smithy just made it back:

I was feeling fairly groggy…Blood was gradually filling my boot up past the knee….more by instinct than anything else, I made a moderately good landing, and then crawled out of the bus and fairly collapsed. They rushed the ambulance up and took me away to the C.S.S, where they operated.25

By his own admission:

It was a marvellous escape, considering there were 180 bullet holes in the machine and dozens round my head, within inches. Fortunately, any that hit the engine didn’t do any damage, and it never "conked out."26

…a certain satanic aspect

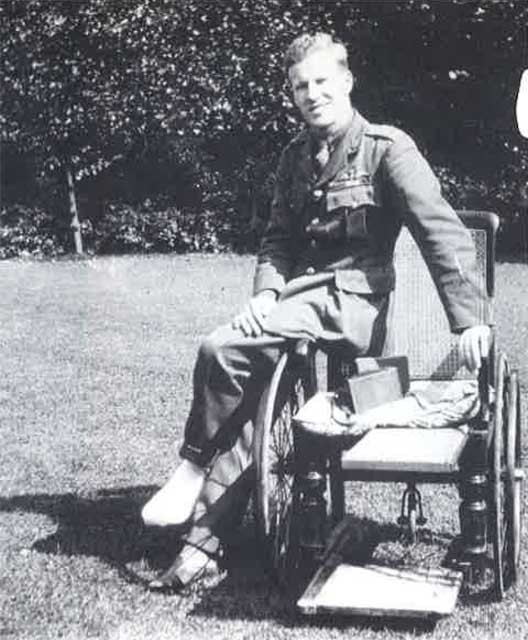

Smithy, like his engine, ‘conked out’ before undergoing surgery. Whilst recovering he wrote home, attaching a gruesome post-operative photo. It showed 2 missing toes and a large v-shaped wound.

As my foot will heal, it will give me a certain satanic aspect- a cloven foot as it were. But it doesn’t matter as long as I can walk all right27

His cloven-hoofed foot gave him pain and a noticeable gait. His mental state was also severely strained. He wrote:

A cablegram boy delivered Smithy’s next message to his home in Neutral Bay. The Kingsford Smith’s would have been relieved:My nerves have gone to the pack. I’m afraid I’m in for a breakdown if they get worse.

Wound improving. Awarded Military Cross

Valuable work or foolish acts?

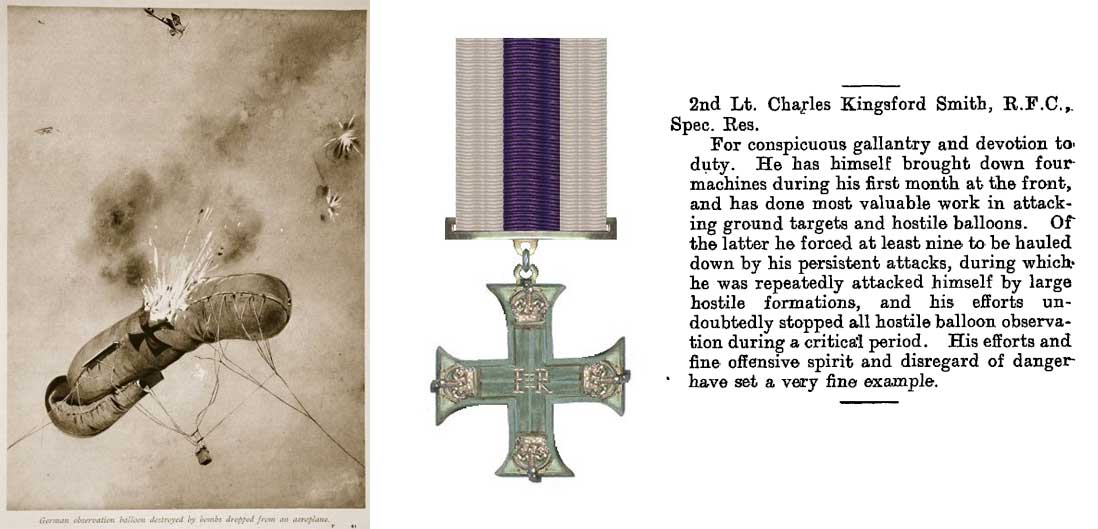

2/Lt. Charles Kingsford Smith’s M.C. was Gazetted on 26/09/1917. His Citation appeared in the Gazette on the 09/01/191828.

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty…His efforts and fine offensive spirit and disregard of danger have set a very fine example

The citation mentions four enemy aircraft as having been shot down during his first month at the front. It also cites:

most valuable work in attacking ground targets and hostile balloons. Of the latter he forced at least nine to be hauled down by his persistent attacks, during which he was repeatedly attacked himself by large hostile formations, and his efforts undoubtedly stopped all hostile balloon observation during a critical period.29

In November he was invited to Buckingham Palace. After George V had pinned an M.C. onto his chest, Smithy following protocol, took a step back. Somewhat embarrassingly, he got tangled up in his crutches and ended up in a heap on the floor. He later would joke that he had been given the award for various acts of foolishness30

…why linger over those hectic days on the Western Front? In our funny old machines, prodigious feats were performed by "intrepid airmen" in things tied up with bits of string, and when it was not unknown for the London Gazette to announce a packet of twenty Military Crosses had been handed out to as many young subalterns and airmen for “distinguished service.”

I managed to shoot down a few "Huns", as we called them in those good old days, and I managed to get wounded and shot down myself. It was service all right, though I doubt whether it was very distinguished, all the time we were youngsters learning a lot. We were imbibing an immense store of flying experience and technical knowledge, and we were learning something to my mind is far more valuable- the capacity to look after yourself, the instinct to do or to die, the desire for action, without of thought of the risks and dangers.

…You hardly ever heard ever heard of an airman having a nervous breakdown in those days, though how we managed to avoid them with all that immense output of energy, I do not know.

I expect it was just youth living off its nerves.31

Pretty, pretty uniform

In early 1918 Smithy returned to Sydney on sick leave. In an interview for the Sydney Morning Herald he sounded his usual upbeat self:

‘The Huns’, he says, ‘are well licked’ and they know it. My opinion is that we have them beaten. The British air service can fairly claim to be superior to that of the enemy; all the facts point to it. The German is a good pilot, but when it comes to actual fighting. In the air he has to play second fiddle to our men. The Australians have their own air service, and are doing remarkably well.

Smithy’s private persona was less brash:

…to the surprise of those that knew him well, Smithy, when he reached home, was retiring almost shy; he was embarrassed by the interest shown by strangers in his distinctive uniform- until a girl, a close friend of the family successfully used guile. She was a pretty girl and Smithy had asked out to afternoon tea…she declared..she was going to wear her best and look her smartest. And if people looked at them, she would be the subject of their admiration. Thereafter, Smithy did not have to be cajoled into wearing his uniform.32

Rather poor quality photo of Smithy in uniform with family. FAMILY ALBUM SNAPSHOT of the late Sir Charles Kingsford Smith in 1916. Smithy, then 19 had been invalided home, having collected the M.C. and foot injuries in a dogfight over France. With him are his sister-in-law, Mrs. Wilfrid Kingsford Smith (left), three of her children, Peter, John (back), Margaret and a family friend.

Rather poor quality photo of Smithy in uniform with family. FAMILY ALBUM SNAPSHOT of the late Sir Charles Kingsford Smith in 1916. Smithy, then 19 had been invalided home, having collected the M.C. and foot injuries in a dogfight over France. With him are his sister-in-law, Mrs. Wilfrid Kingsford Smith (left), three of her children, Peter, John (back), Margaret and a family friend.

By VICKI ANDERSON Source: Pittwater Online News

Not all the attention to his uniform was positive. One day Smithy and his brother Leof were taking their seats on the Mosman ferry boat:

…If his limp, which still demanded the use of a walking stick, added a touch of romance, it did not register with a pair of young men, apparently able bodied…One of the two strangers looked at Smithy and then, grinning, spoke to his companion. Smithy caught the term “pretty, pretty uniform.” Dropping his stick, he swung towards the pair, grasped the neck of each of his suspected detractors, and bashed their heads together resoundingly. He said nothing. He joined Leof as if nothing had happened. Smithy was always strong in action, weak on explanations.33

The only official duty Smithy performed on his leave was to investigate a reported sighting of aircraft over The Entrance, Tuggerah lakes:

This proved to be a false alarm as Smithy declared them to be nothing more than a flight of large birds.34 [ Pelicans? ]

King Dick

No. 19 Squadron RFC with Smithy second row, second from the right- the one with no cap.

Smithy finished the war, like many pilots with frayed nerves, as an instructor. His injuries, however, didn’t impede his rampant womanizing. One of his fellow instructors recalled:

He enjoyed life to the full and he enjoyed especially the company of young ladies35

King Dick was without doubt the fastest worker.. we were billeted at a hotel where 2 girls were resident.. He amazed us all by sampling the bed-worthiness of both within a couple of days. At the same time he was having an affair with an Italian violinist playing in the orchestra up in London. He just seemed to hypnotise women.36

The Blackburn ‘Kangaroo’ Smithy was meant to pilot crash-landed in Crete. Note the registration letters G-EAOW, translated by the crew as: ‘England-Australia On Wings’ Source: ‘The Greatest Air Race’ by Nelson Eustis.

The Blackburn ‘Kangaroo’ Smithy was meant to pilot crash-landed in Crete. Note the registration letters G-EAOW, translated by the crew as: ‘England-Australia On Wings’ Source: ‘The Greatest Air Race’ by Nelson Eustis.

Smithy desperately wanted to enter the 100,000 (GBP) prize air race from Britain to Australia. But he’d tarnished his name over a commercial flying venture in the UK. His joy flights with young ladies to secluded spots raised eyebrows, but other commercial indiscretions could not be ignored.

Smithy and his crew had acquired aircraft on the cheap from war surplus to set up a private flying service. Subsequent mishaps with a succession of aircraft, and insurance claims for amounts higher than their actual value came to the attention of British authorities. It may have been just bad luck, and a bit of opportunism, but that’s not how it was seen by those in decision making circles.

Smithy was stung by this rejection. His ambition to win fame and fortune had suffered a serious set-back.

The race was won by 2 other Smiths, Ross and Keith in their Vickers Vimy.

From Britain Smithy traveled to the U.S. Flat broke, he took up work as a stunt pilot in California. This was short lived. As the below picture below shows he became stuck suspended in flight, and was lucky to have not been killed.

Charles Kingsford Smith stunting for the movies, California, 1922. After serving in Australian squadrons in the Royal Flying Corps in World War 1, Kingsford-Smith travelled to Hollywood to do stunt flying. Among the stunts were wing-walking and hanging by his legs from undercarriages. (NLA 3723531)

Charles Kingsford Smith stunting for the movies, California, 1922. After serving in Australian squadrons in the Royal Flying Corps in World War 1, Kingsford-Smith travelled to Hollywood to do stunt flying. Among the stunts were wing-walking and hanging by his legs from undercarriages. (NLA 3723531)

Smithy returned to Australia, attempting commercial ventures. He lived for a time with his parents at Longueville, Lane Cove.

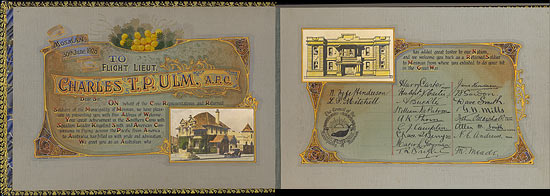

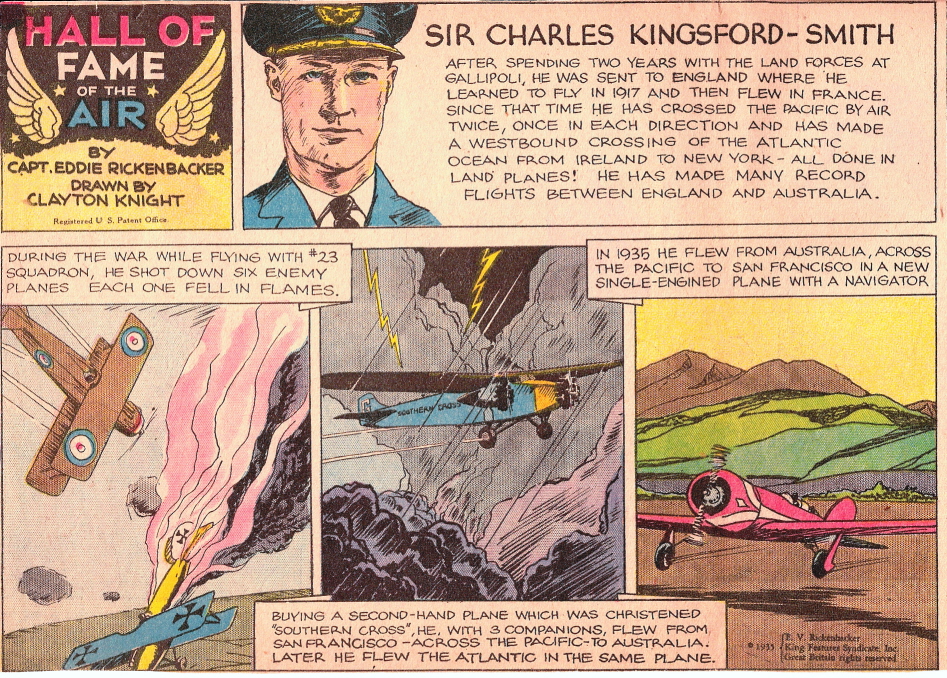

Smithy realised most of his dreams, flying in record breaking flights. These included crossing the Pacific Ocean in 1928 and 1934 with Mosman aviators, Charles Ulm and ‘Bill’ Taylor.

He and his aircraft disappeared making yet another record breaking attempt in 1934. He was survived by his family, wife and young son.

Follow the Smithy story

Where angels fear to tread: Smithy’s baptism of fire

1919 Air Race: Why Smithy couldn’t fly the Kangaroo

Mosman’s ‘right royal welcome’ to Pacific Fliers: Smithy & ‘Alphabet’ UlmSmithy’s treasured postcard from actress Nellie Stewart

Recommended reading / Bibliography

Ellison, Norman and Kingsford-Smith, Charles, 1897-1935 Flying Matilda : early days in Australian aviation. Angus and Robertson, Sydney, N.S.W, 1957.

Kingsford-Smith, Charles and Rawson, Geoffrey My flying life : an authentic biography prepared under the personal supervision of and from the diaries and papers of the late Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith. A. Melrose, Ltd, London, 1937.

Mackersey, Ian Smithy : the life of Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith. Little, Brown & Co, London, 1998.

Stannage, John and Kingsford-Smith, Charles, 1897-1935 Smithy. Geoffrey Cumberlege, Oxford University Press, London, 1950.

Footnotes

1 Mackersey, Ian Smithy : the life of Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith. Little, Brown & Co, London, 1998. p19

2 Kingsford Smith’s family lived close by, in Yeo Street Neutral Bay [No. 68], but also had Mosman connections-two of his brothers married Mosman girls, and Smithy is said to have played tennis with friends in Mosman. Source: Morris, Phillipa Mosman salutes those magnificent aviators retrieved online 24/05/17. Smithy’s parents lived in Shadforth St in 1918. Source: Blainey, Anne The turbulent life of Charles Kingsford Smith Black Inc. Carlton, VIC 2018 p.57

3 Mackersey, Ibid

4 Ellison, Norman and Kingsford-Smith, Charles, 1897-1935 Flying Matilda : early days in Australian aviation. Angus and Robertson, Sydney, N.S.W, 1957.

5 Mackersey p. 22

6 As a Sergeant with 4th Div. Signal Co.

7 Mackersey, p. 23

8 Ellison, Norman and Kingsford-Smith, Charles, 1897-1935 Flying Matilda : early days in Australian aviation. Angus and Robertson, Sydney, N.S.W, 1957.

9 His family background and private schooling would have helped. A lot of pilots had to embellish their applications in regards age and education in order to be considered.

10 Ellison, Norman and Kingsford-Smith, Charles, 1897-1935 Flying Matilda : early days in Australian aviation. Angus and Robertson, Sydney, N.S.W, 1957.

11 ‘At the age of seventeen, Eric had been apprenticed to the sea. By the time he joined up with the Royal Australian Navy in 1913 he had seen a good deal of the world, and a great deal of life. He was on the H.M.A.S. Sydney when she fought and defeated the German raider-cruiser Emden. In his love of adventure and zest for life he was truly Smithy’s brother, and he almost beat young Charles into the air. When he was on duty in the West Indies he was filling in an application for transfer to the Royal Naval Air Service, when an Admiralty signal arrived decreeing that no more transfers would be granted; too many officers had already changed over to ships of the air.’ Source: Ellison, Norman and Kingsford-Smith, Charles, 1897-1935 Flying Matilda : early days in Australian aviation. Angus and Robertson, Sydney, N.S.W, 1957.

12 Ellison, Norman and Kingsford-Smith, Charles, 1897-1935 Flying Matilda : early days in Australian aviation. Angus and Robertson, Sydney, N.S.W, 1957.

13 For a total of 46 hrs solo flying experience. The SPAD was designed by a French Company founded by Bleriot, who made the historic 1st flight across the English channel. The were built by both British and French companies.

14 Ellison, Norman and Kingsford-Smith, Charles, 1897-1935 Flying Matilda : early days in Australian aviation. Angus and Robertson, Sydney, N.S.W, 1957. p 225. Elllison notes ‘Australians in particular will note in this letter Smithy’s use of the term ‘old bus’, a term which he was to write into air history.’

15 Ibid. p. 229

16 Ibid

17 Ibid

18 Ibid p.230

19 Ibid

20 Retrieved 28/07/17 www.theaerodrome.com/services/gbritain/rfc/23.php

21 Years later Smithy co-authored his war experiences with his radio-operator John Stannage, (Smithy Oxford University Press, London, 1950.)

22 Mackersey, Ian Smithy : the life of Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith. p. 29

23 Ellison, Norman and Kingsford-Smith, p. 232

24 There are some doubts about whom Reinhard shot down on this day GWF: 1914-1918.invisionzone.com/forums/index.php?/topic/233100-23-sqn-rfc-and-kingsford-smith retrieved 28/07/17

25 Ellison, Norman and Kingsford-Smith, p. 233

26 Ibid p.233

27 Ibid p.234

28 Supplement to the London Gazette 9 January 1918 www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/30466/supplement/643/data.pdf retrieved 28/07/17

29 Ibid.

30 Kingsford-Smith, Charles and Rawson, Geoffrey My flying life : an authentic biography prepared under the personal supervision of and from the diaries and papers of the late Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith. A. Melrose, Ltd, London, 1937.

31 Ibid

32 Mackersey, p. 33

33 Ibid

34 Ibid

35 Ibid

36 Ibid