Pandemic 1918

I’m currently reading Pandemic 1918: The Story of the Deadliest Influenza in History by Catherine Arnold.

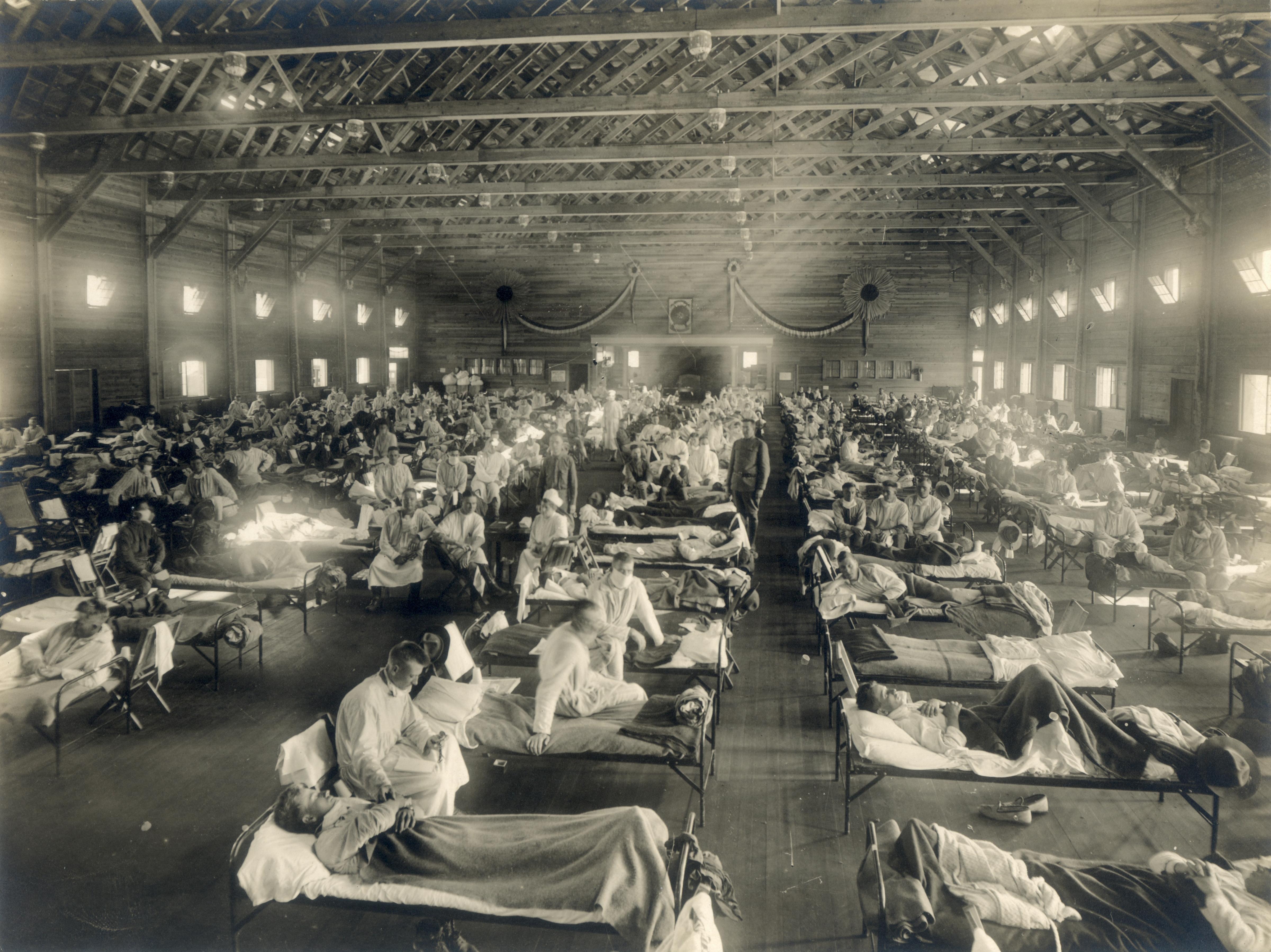

Training grounds in the US provided the perfect environment for an outbreak. Recruits crowded into dormitories, breathed in dust storms and burning manure, and became susceptible to strains of swine and horse flu or viruses from sick Chinese labourers crammed into trains heading through North America to dig trenches in Europe.

John Steinbeck, the famous writer, had a close call with the deadly respiratory infection.

I went down and down until the wingtips of angels brushed my eyes

His doctor removed a rib to drain a lung of infection. Steinbeck did recover but was haunted physically and emotionally by the experience, as many were for a long time afterward.

I highly recommended the above title. Especially because of the first and second-hand sources used to illustrate the impact of this ‘holocaust’ on people from all walks of life. It’s like watching a train crash in slow motion the way Arnold brings this to life. It’s hard to put down, even though you wish you could.

The book review below provides more detail about the 1919 Pandemic.

The Spanish Flu Epidemic

Another book about the 1919 pandemic published just before the current Covid 19 event is The Spanish Flu Epidemic and Its Influence on History by Jaime Breitnauer .

It has short and interesting chapters and is a good introduction to the subject.

The author writes in a fictional style so the reader can empathize at the random and unfathomable nature of death from the invisible enemy.

Whilst researching I found mostly dry and uninformative newspaper articles and official reports, first-hand accounts are rare. So in that way, the author’s approach is a good one. I would caution in general, however, about writing history with too much imaginative interpretation.

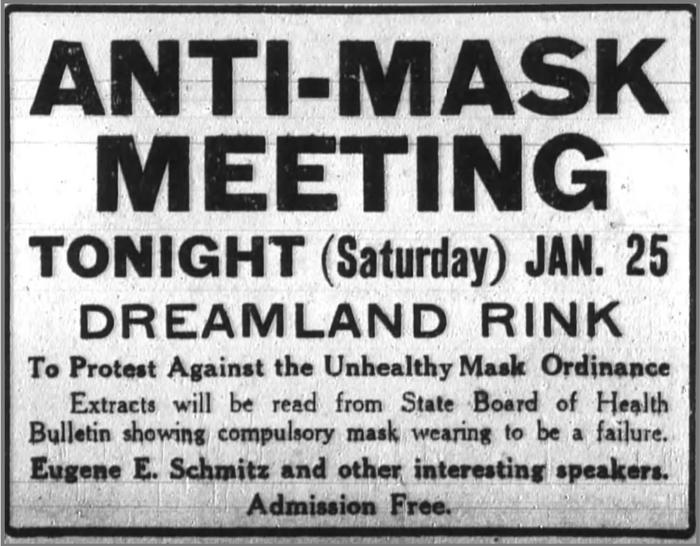

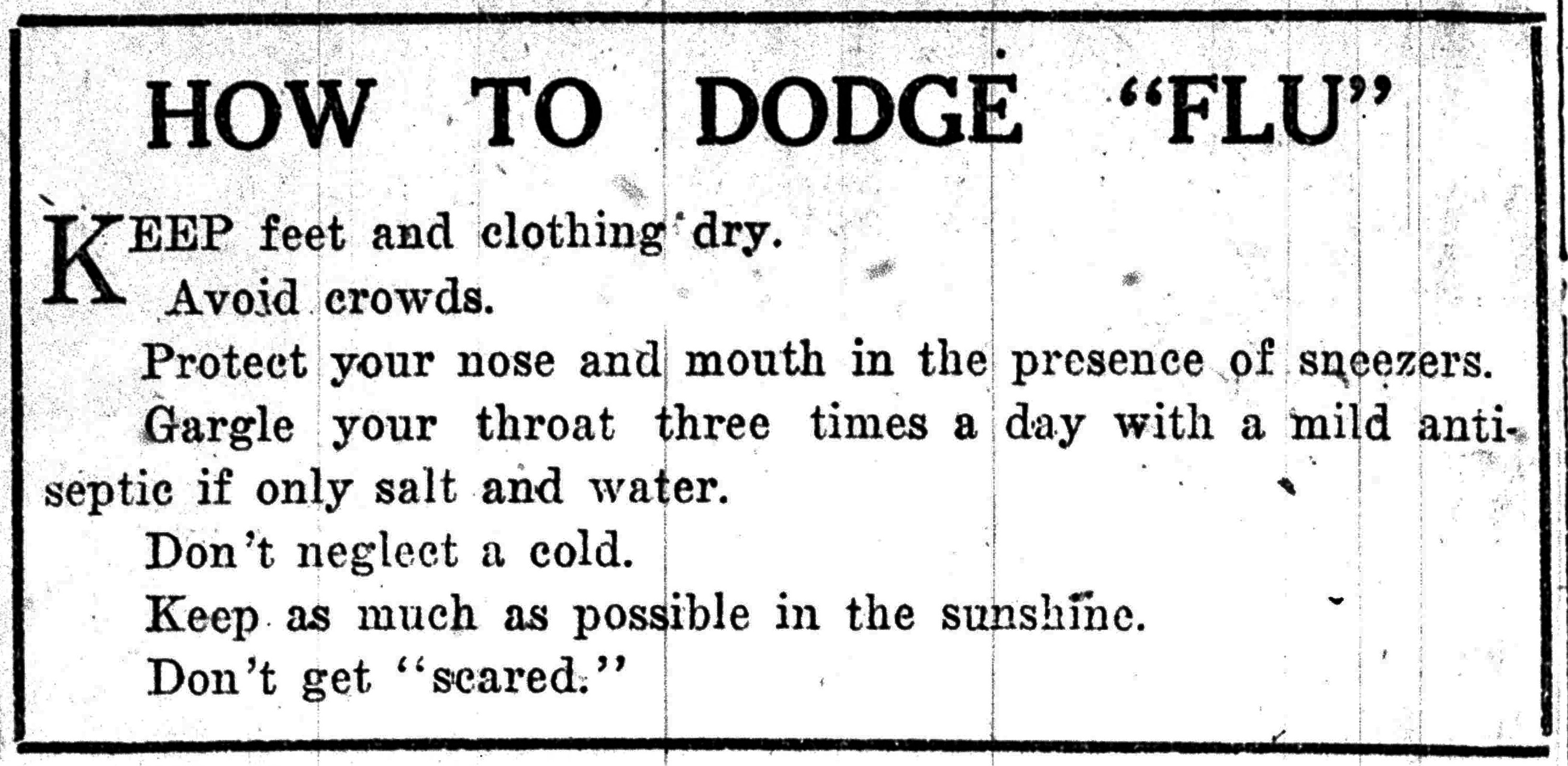

That said the author’s bibliography is comprehensive. As Brietnauer correctly states this tragedy has been swept under the historical carpet, overshadowed by the war before it, even though the pandemic took more lives. And It is definitely a story worth telling. Especially now. I was amazed how similar both pandemics have played out, and in particular how authorities have tried and failed to get on top of the spread. Our technology and communications systems have us in a better position than one hundred years ago as you would expect.

The author raises interesting points:

- There were initial outbreaks in China before the war. A strain could have been carried by labourers sent in confined trains across Canada to Europe to dig trenches in Europe. One strain definitely emanated from farms in the American mid-west. Training grounds in the US provided the perfect starting point, and then it reached the trenches and civilian population from soldiers en route to the front, mixing with other strains already circulating.

- The virus then spread rapidly through the trenches on both sides, substantially weakening manpower. It is suggested that the German’s huge offensive in 1918 was undermined by the amount of men down dropping like flies from the ‘flu.

- From the trenches, it made its way all around the world. Servicemen returning home contributed to its spread. Civilian and indigenous populations, like the troops, were malnourished from years of war and were devastated. The first wave seemed to hit the old, children, and pregnant women. The second took younger people, sometimes within hours of showing symptoms. The third got everyone. The author gives memorable detail of the sudden and terrible impact on families and communities.

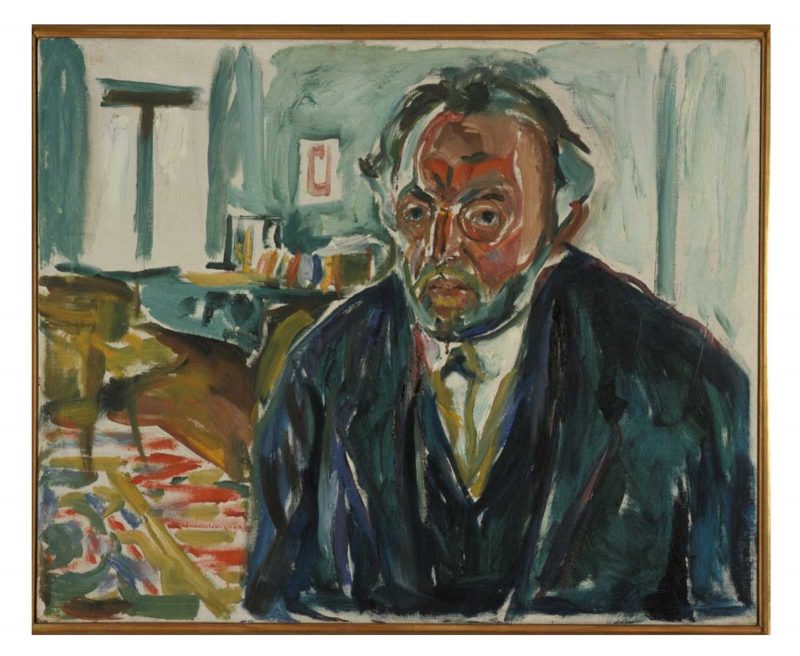

Edward Munch “Self Portrait With Spanish Flu” (1919) oil/canvas, Munch Museum, Oslo

Edward Munch “Self Portrait With Spanish Flu” (1919) oil/canvas, Munch Museum, Oslo

‘Edith Schiele on her Deathbed’ (1918) by Egon Schiele. Chalk on paper, Leopold Museum, Vienna

‘Edith Schiele on her Deathbed’ (1918) by Egon Schiele. Chalk on paper, Leopold Museum, Vienna

- I was interested to learn Viennese artist Egon Schiele’s wife and unborn child succumbed to the virus. Devastated by the loss, he died 3 days later, weakened by the disease. It was a sad irony his themed paintings on death and motherhood came to be realised at his life’s end. His friend and fellow artist Gustav Klimt also narrowly survived a bout of the dreaded lurgy, as did many.

- It is called ‘The Spanish flu’ because Spain being neutral did not censor its news, and reported the first cases.

- Scientist thought that the infection was bacterial. Its identification as a Virus wasn’t until 1933. So all efforts to fight to bug were in vain.

- Those that recovered from the virus suffered physical and psychological after-effects for years afterward.

The virus had some indirect impacts on ‘big history’ as well:

- It showed up the indifference of the British colonial enterprise to the needs of Indian people, prompting the movement to Independence led by Gandhi, among others.

- The Sykes-Picot agreement affecting the future of the Middle East, went ahead at Versailles. It may be that Sykes was having doubts about his proposal, but he died of the flu before the final draft was tabled.

- As mentioned the German war effort was seriously eroded with men unable to fight.

More reading:

- Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How it Changed the World by Laura Spinney, 2017

And first out of the Covid blocks:

- The Pandemic Century: A History of Global Contagion from the Spanish Flu to Covid-19 by Mark Honigsbaum, April 2020