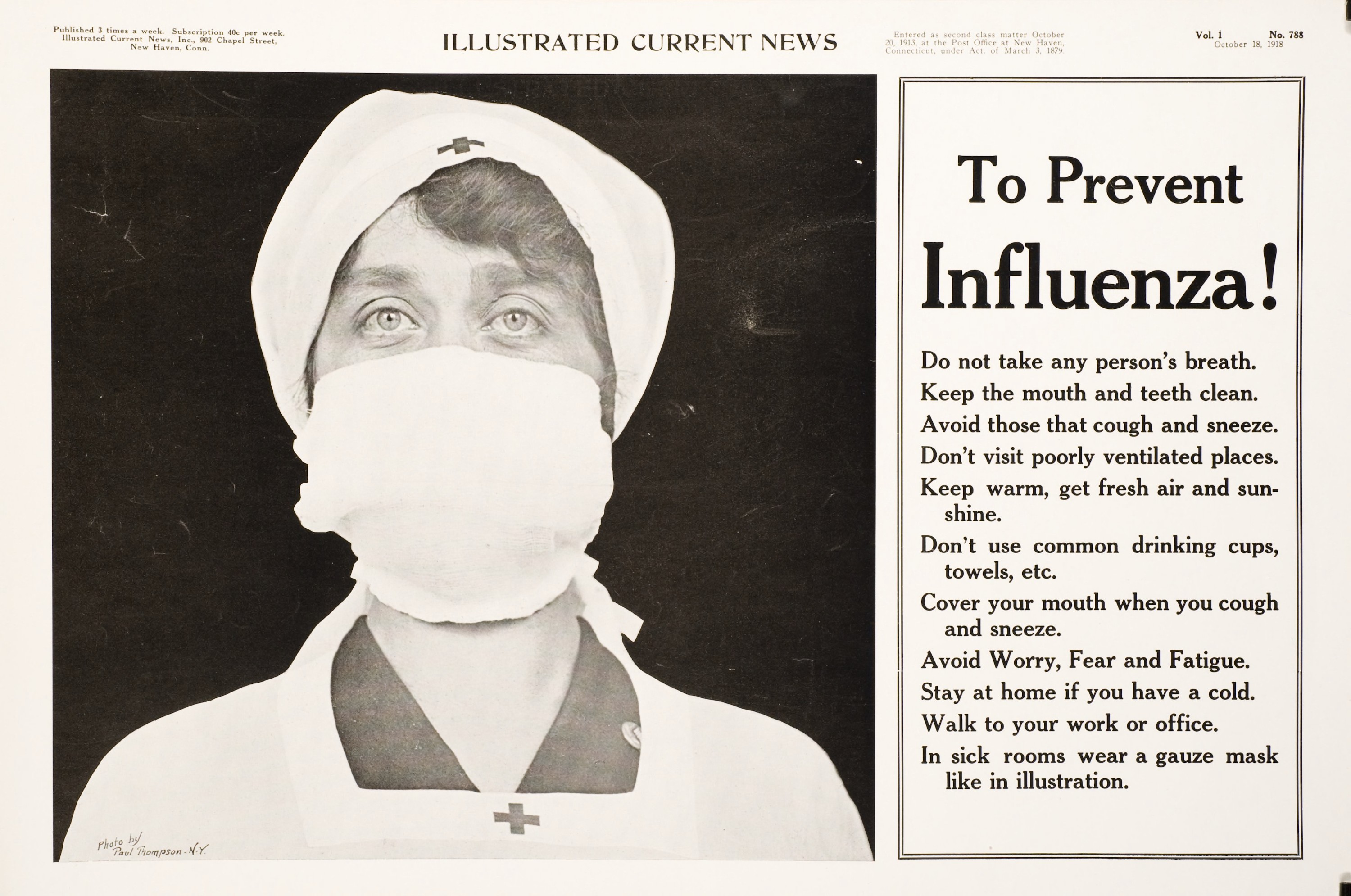

Prevent Influenza, Illustrated Current News, October 18, 1918 NLM Image ID: A032746

Prevent Influenza, Illustrated Current News, October 18, 1918 NLM Image ID: A032746

The invisible enemy

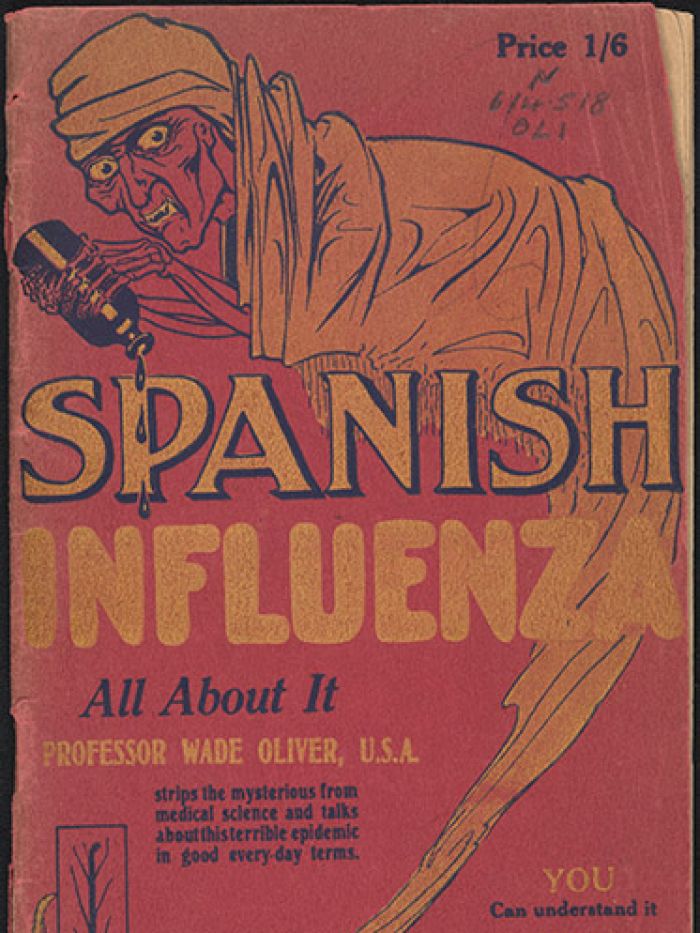

Six months before the end of the Great War a new and deadly strain of Influenza emerged.

The disease flourished in the trenches, and the mass movement of armies to and from Europe aided its spread to all continents. The virus took up to 50 million or more lives,1 of all ages.

Australia kept strict quarantine conditions from October 1918:

By late January 1919 it was compulsory in Sydney to wear a surgical mask in the street, in a building or on public transport. Theaters, hotels. schools and telephone boxes were closed, and race meeting and church services were shut down.2

The influenza pandemic/epidemic seriously affected everyday activities and services. There were only 2000 hospital beds in NSW at the start of the pandemic. Between January and September 1919 25,000 people in NSW were admitted to hospital with influenza. Obviously it took its toll on medical and healthcare workers. In Sydney many temporary hospitals had to be staffed by lay volunteers.3

Medical staff and workers from Riley Street Depot, Surry Hills, April 1919. Picture: NSW State Archives and Records

Medical staff and workers from Riley Street Depot, Surry Hills, April 1919. Picture: NSW State Archives and Records

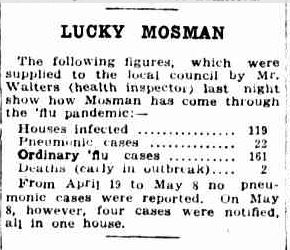

Lucky Mosman

Gavin Souter, Mosman historian, wrote:

As happened in many communities, schoolchildren often wore face masks, with camphor bags also slung hopefully around their necks for good measure. In April when eleven cases of pneumonic flu were reported in Mosman, the Council (unnecessarily, as it turned out) insured it’s sanitary Inspector’s life for the next six months at a premium of 7 [pounds], 3 s 4 p.4

…the Mulligan family show Mosman was not immune to the pneumonic influenza pandemic that swept the world in 1918, taking with it more casualties than World War I… Masked members of the Mulligan family, (L –R) Martha Mulligan holding baby James, Beatrice Mulligan, Maggie Hamilton (household help), in front Beryl Mulligan and Phyllis Mulligan in the garden of their home Seborf, 14 Clifford Street. More of Jill Mercer’s memories can be found on mosmanmemories.net Source: Barry O’Keefe Library’s image archive: Trace

…the Mulligan family show Mosman was not immune to the pneumonic influenza pandemic that swept the world in 1918, taking with it more casualties than World War I… Masked members of the Mulligan family, (L –R) Martha Mulligan holding baby James, Beatrice Mulligan, Maggie Hamilton (household help), in front Beryl Mulligan and Phyllis Mulligan in the garden of their home Seborf, 14 Clifford Street. More of Jill Mercer’s memories can be found on mosmanmemories.net Source: Barry O’Keefe Library’s image archive: Trace

Mr Walters, the health inspector for Mosman Council was kept busy. But as The Sun implied, Mosman had fewer cases than other suburbs. It’d been ‘lucky’. The Sun reported on the 14th of May, 1919:

LUCKY MOSMAN

The following figures, which were supplied to the local council by Mr. Walters (health inspector) last night

shows how Mosman has come through through the flu pandemic; —

Houses Infected………………119

Pneumonic cases……………..22

Ordinary ‘flu cases…………..161

Deaths (early in outbreak)…..2

From April 19 to May 8 no pneumonic cases were reported. On May 8, however, four cases were notified, all in one house.

Joyce Robinson was four at the time of the pandemic. She could be counted luckier than her family members who fell ill, and would have been part of Mr Walter’s caseload. Interviewed for the Mosman Voices project in 2001, she recalled:

I can just remember the bad flu that was in 1919, just after we moved back here. My aunt and her family were living in the house next door to us. My mother, my father and my brother all went down with it, and my aunt, her husband and two children went down with it. But Aunty Lou looked after me. All I can remember about it is her taking me through a gap in the fence between the two, and I had to wear this white mask, because I was only four at the time.

A girl stands next to her sister, who is lying in bed fighting the influenza virus, in November 1918. The young girl became so worried that she telephoned the Red Cross Home Service, which came to help care for the woman, whose husband was on the battlefield in France. Source/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

A girl stands next to her sister, who is lying in bed fighting the influenza virus, in November 1918. The young girl became so worried that she telephoned the Red Cross Home Service, which came to help care for the woman, whose husband was on the battlefield in France. Source/Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

The hospital on the hill.

St Georges Heights, NSW. The interior of a busy ward at No 21 Australian Auxiliary Hospital. Source: AWM H18457

St Georges Heights, NSW. The interior of a busy ward at No 21 Australian Auxiliary Hospital. Source: AWM H18457

Georges Heights hospital treated injured soldiers returned from the war. After the war it was to become a naval hospital for cases of venereal disease. Mosman Council asked the Member for North Sydney ‘to obtain an understanding from the Health Department that this would not happen, and two months later he reported that the hospital would not be transferred to the navy as it was still required by the army.’5

Staff at the Georges Heights Hospital during the Pandemic

Staff at the Georges Heights Hospital during the Pandemic

Staff and patients at the hospital survived the 1919 pandemic:

The medical profession argued about what caused the flu, came up with a number of theories,but proved no better able to deal with it than anyone else. You caught it, sweated it out, and survived – or perished. The hospitals were swamped with cases, but by the end of 1919 only 12, 000 Australians had died. At Georges heights, all strict measures were taken and there were no fatalities.6

St Georges Heights, NSW. Top: The Headquarters building of No 21 Australian Auxiliary Hospital with three AIF officers standing on the verandah. Source: AWM H18459 Below: The building in use today as artist studios and exhibition space (the building behind is now a cafe)

St Georges Heights, NSW. Top: The Headquarters building of No 21 Australian Auxiliary Hospital with three AIF officers standing on the verandah. Source: AWM H18459 Below: The building in use today as artist studios and exhibition space (the building behind is now a cafe)

The soldier to the right in the old photo above has been identified as Lt Alan Brierley. He met volunteer-carer Alice Pope whilst rehabilitating, and they later married:

Alan and Alice after the war. Source: Romance at Georges Heights Hospital

Alan and Alice after the war. Source: Romance at Georges Heights Hospital

The epidemic persisted through the winter of 1919. As a result Peace Treaty in Versailles celebrations were postponed. The Officer in Charge of the Influenza Emergency Department in Bridge St, Sydney, also announced the setting up an emergency depot at North Sydney:

The North Sydney center was located at St. Peter’s Hall in Blue’s Point Road and included Manly, Warringah, Mosman, North Sydney, Willoughby, Naremburn, Lane Cove, Kuringai and Hornsby. (A long way to travel in horse buggy for those needing emergency medical attention I would think!)7

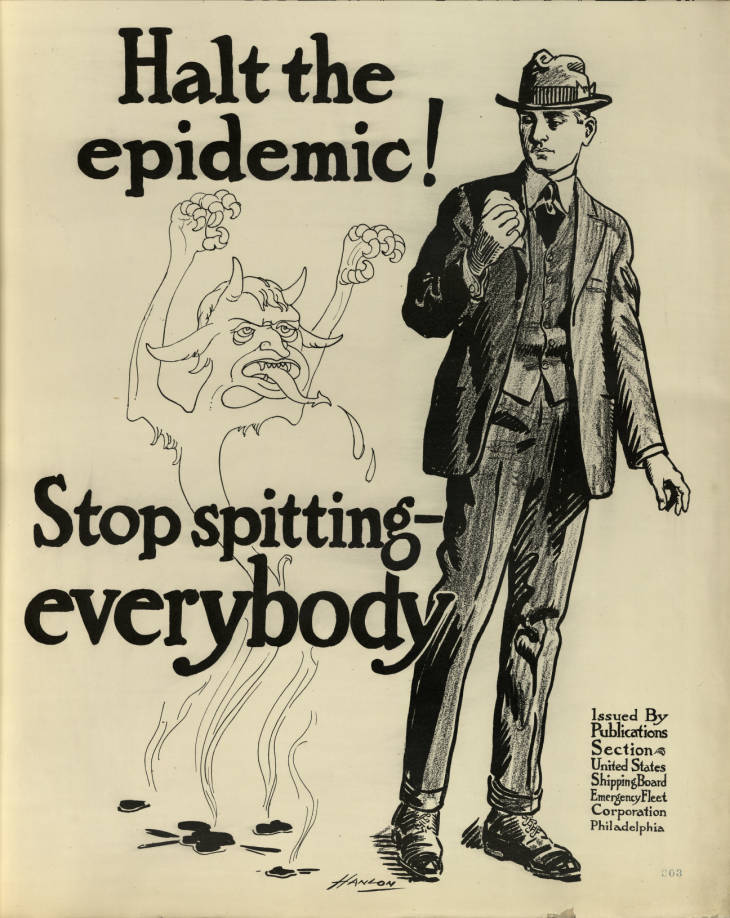

The beastly illness.

In a letter to the editor of the Leader in Melbourne on the 5th October 1918, one reader described coming down with the flu. Anyone who has had the following symptoms can relate to the experience:

It began yesterday. In the morning I was very cheerful, having just made definite arrangements for my holiday to start at the end of this week. At lunch time I suddenly detected a violent and unpleasant

headache, and I discovered that my forehead was burning. By 4 o’clock I was beginning to wonder what there was that other people found attractive in life. I felt moist and hot all over, my head weighed tons and ached intolerably, my eyes were on fire, and I had violent pains in my back, and legs, and arms.

Halt the epidemic! Source: Temple Universities digital collection

I wrote a hurried note to cancel all my arrangements for my holidays, and, thinking it would be nicer to die at home than in the city, I hurried from my office.

In the railway carriage people did not notice that I was on the point of death, and I had to stand. At times my legs wereso weak that I had to “strap-hang” with all my strength—which was not very much. Every now and then the pains ceased, and I felt curiously light-headed and “detached“—nothing mattered. And then the pain would come on again, and show me very conclusively that it mattered a lot.

My only consolation was that, very indirectly, I might have caught the beastly illness from the King of Spain himself, but when I thought of the thousands of others who might have done the same thing I realised that the distinction was not very great. I went to bed depressed and feverish

and miserable. This morning I found the sun still shining, and was a little annoyed that I had orders to stay in bed all day. At lunch my wife told me I was eating too much. This afternoon I wrote to cancel my cancellation

of my holiday arrangements. The world this evening is a much nicer world than it was yesterday.

The tail end

A sepia photograph showing male and female staff using an ‘inhalatorium’ at the Kodak Australasia Pty Ltd factory in Abbotsford. The inhalatorium was used to protect workers from being infected with the influenza during the 1919 Spanish flu epidemic. Ten people could be accommodated on each side of the structure, from which steam carrying sulphate of zinc solution was sprayed onto the worker’s faces. Once breathed in it was thought that the steam solution would ‘disinfect’ the workers’ throats and air passages. Staff were given this treatment twice a day for four minutes at a time, and were advised to take about 15 slow, deep breaths. Source: Trove

A sepia photograph showing male and female staff using an ‘inhalatorium’ at the Kodak Australasia Pty Ltd factory in Abbotsford. The inhalatorium was used to protect workers from being infected with the influenza during the 1919 Spanish flu epidemic. Ten people could be accommodated on each side of the structure, from which steam carrying sulphate of zinc solution was sprayed onto the worker’s faces. Once breathed in it was thought that the steam solution would ‘disinfect’ the workers’ throats and air passages. Staff were given this treatment twice a day for four minutes at a time, and were advised to take about 15 slow, deep breaths. Source: Trove

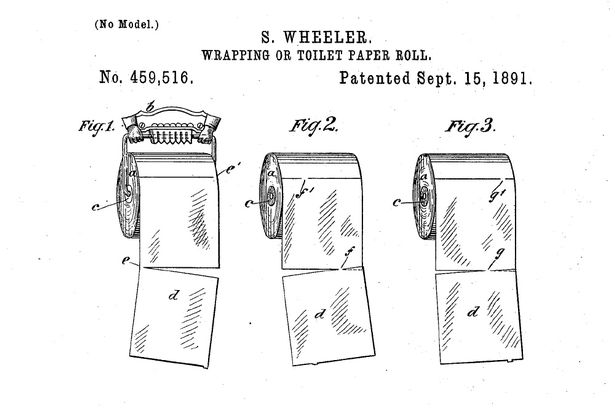

The impact on the sale of household supplies in 1919 requires further research. Toilet paper of some sort would have been commercially available in 1919:

The use of paper for hygiene has been recorded in China in the 6th century AD, with specifically manufactured toilet paper being mass-produced in the 14th century. Modern commercial toilet paper originated in the 19th century, with a patent for roll-based dispensers being made in 1883…The manufacturing of this product had a long period of refinement, considering that as late as the 1930s, a selling point of the Northern Tissue company was that their toilet paper was “splinter free”8

The author has found no evidence, so far, of panic buying of this product during the Spanish flu epidemic.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Source: Wikimedia Commons

A message during the current pandemic

Accademia library reading room, Rome with Globe. ‘Hmm…Terra Australis needs some filling in…!’

Wishing you and your loved ones all the best in the current crisis…keep calm and carry on..

Remember to take all precautions, including double checking social media sources. For example a letter supposedly written by F. Scott Fitzgerald in Italy during the 1919 epidemic.

Stay safe and healthy, go for walks, keep connected, reading and… ‘doing your bit!’

And a big thanks to our front-line hospital staff and anyone else involved in defeating Covid

Staff from the Georges Heights Hospital taking a break

Staff from the Georges Heights Hospital taking a break

Related articles

Recommended links:

General;

Doing Our Bit stories marking 100 years since the Great War

Relevant to the Pandemic! story;

Doing Our Bit Mosman 1914-18 Blog story Romance at Georges Heights Hospital

Mosman register of notification of infectious diseases, 1898-1966.

RAHS An Intimate Pandemic: The Community Impact of Influenza in 1919

Source: Trace

ABC News: How does coronavirus compare to Spanish flu? COVID-19 has important differences to the 1918 outbreak

The Guardian: Spanish flu: the killer that still stalks us, 100 years on

A search of Barry O’Keefe’s Trace digital archive reveals photos of families during the 1919 pandemic.

Footnotes:

1 Wikipedia Spanish flu sites 17-50 million, and up to 100 million

2 Fletcher, Patrick (2012). The Hospital on the Hill : recollecting a hospital of the First World War. Mosman, N.S.W. Sydney Harbour Federation Trust p.99

3 Wade, Susan Wading through the Archives: The Influenza Pandemic, 1918 – 1919 in North Shore Historical Society for AUGUST 2016

4 Souter, Gavin (1994). Mosman: a history. Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic p.159-60

5 ibid

6 Fletcher, Patrick ibid

7 Wade, Susan ibid

8 Wikipedia online Toilet paper retrieved 9/3/20