Billy Hughes assumed the majority of Australians would support him. Those remaining, he thought, could be persuaded or brow-beaten into accepting the YES case. Instead, his campaign divided the nation. In the words of historian Joan Beaumont:

The fault lines along which Australian society divided on conscription were complex, and are still not entirely clear… However, with some important exceptions, Australians voted in ways which reflected their class, religion and gender, with class perhaps the dominant variable…It was a long campaign, lasting eight weeks, and public order soon disintegrated. Each side held mass rallies, often in the open. Crowds numbered up to 100,000 in Sydney.11

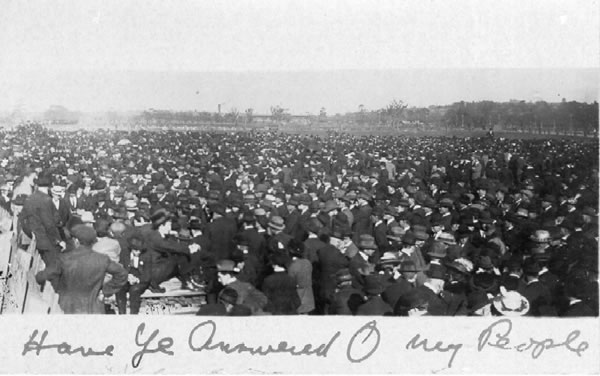

This is a postcard showing a huge crowd at an anti-conscription rally on the banks of the Yarra River in Melbourne in 1916. The image shows a sea of men and a sprinkling of women standing in an open area. A handwritten note under the photograph (penned by John Curtin) reads ‘Have Ye Answered O my People’ and another on the back of the postcard reads ‘Not a bad crowd to bang at’. ‘Kodak Australia’ is printed on the back of the card. Source: John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library; http://john.curtin.edu.au/education/tlf/R2991/00687157_image/index.html

This is a postcard showing a huge crowd at an anti-conscription rally on the banks of the Yarra River in Melbourne in 1916. The image shows a sea of men and a sprinkling of women standing in an open area. A handwritten note under the photograph (penned by John Curtin) reads ‘Have Ye Answered O my People’ and another on the back of the postcard reads ‘Not a bad crowd to bang at’. ‘Kodak Australia’ is printed on the back of the card. Source: John Curtin Prime Ministerial Library; http://john.curtin.edu.au/education/tlf/R2991/00687157_image/index.html

Hughes started the campaign by addressing his traditional supporters. He reached deep into his bag of ‘oratorical, logical and political tricks to convert all, or at least some… to support his referendum campaign’.12

But to no avail. The majority of Labour politicians and rank-and-file remained sceptical. They resolved on a resounding NO.

So he turned to middle-class and conservative voters more receptive to his call to arms.

The prime minister W M Hughes speaking in Martin Place, Sydney, 1916.

The prime minister W M Hughes speaking in Martin Place, Sydney, 1916.

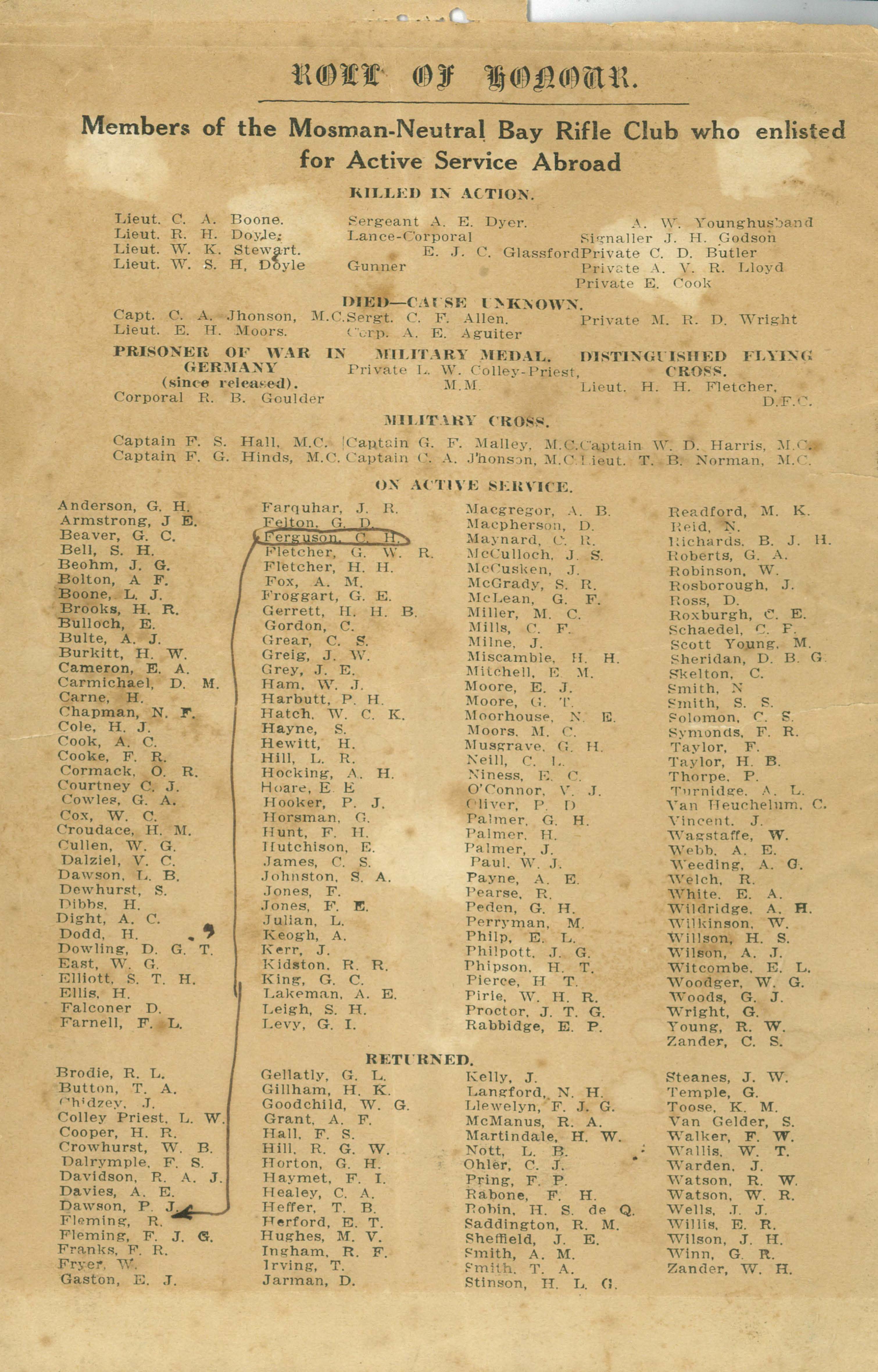

Mosman votes YES:

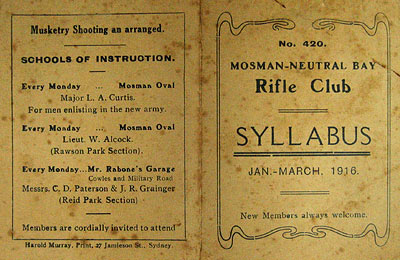

Conscription favoured by Riflemen.

The Mosman-Neutral Bay Rifle Club/Association had supported the war by training volunteers. The club also raised funds for Belgian war victims and organized a patriotic carnival (shooting competition) in 1915. In 1916 it hosted concerts and sent comfort packages to the troops (filled with goodies such as knitted socks, postcards and food.)

The Daily Telegraph reported13 on their 2nd AGM in July 1916. The proposal to support Conscription was passed ‘by an overwhelming majority’, with only a few questioning whether the club should get involved in the debate:

At Friday night’s meeting…. Mr A. G. Gilchrist moved, -

“That this meeting considers the time has now arrived when conscription should be brought into force in Australia to assist in bringing this terrible war to a speedy and satisfactory conclusion, and that copies be sent to the Universal Service League14 and the daily press.”

Mr. Gilchrist said they did not like conscription.

“But it was not a case of liking but one of national necessity.”(Cheers.)

Mr. Heath, who seconded the motion, said he was a married man with responsibilities. There were any amount of available young men and for that reason, he seconded the motion.

The point was raised as to whether the club, a military organisation, had the right to pass a motion ‘of that sort.’ (that is, of a political nature.)

A voice: We are only semi-military.

Mr. Gilchrist: So far as a military body is concerned I think we are semi-mongrel. (Loud laughter.)

Appeals were made to withdraw the motion, but Mr Gilchrist refused.

A voice: Only recently a letter was issued by the State Commandant asking soldiers to keep away from anti-conscription meetings. I think we as a military body are in the same plight. It would be better for them to join the Universal League as private citizens. Mr. Rex said they were only sworn in to defend Australia, and nothing else. The chairman (Mr. J. C. Cargill) said they might be wrong in passing the motion and also sending it to the press.

A voice: What will the penalty be? (Laughter.)

The chairman: I do not know. We may be disbanded. The question remains, ought we to do it?

Chorus of “Yes.”

The chairman said he would not rule the motion out of order, but he would ask them to consider whether it was advisable in the interests of the club and military discipline.

Voices: Put the motion.

A voice: What is the difference between a soldier and a civilian?

Cries of “The uniform.”

An amendment was moved that the motion be deferred for 30 hours.

Cries of “No’”

The motion was then carried by an overwhelming majority.

MOSMAN COUNCIL TAKES ACTION

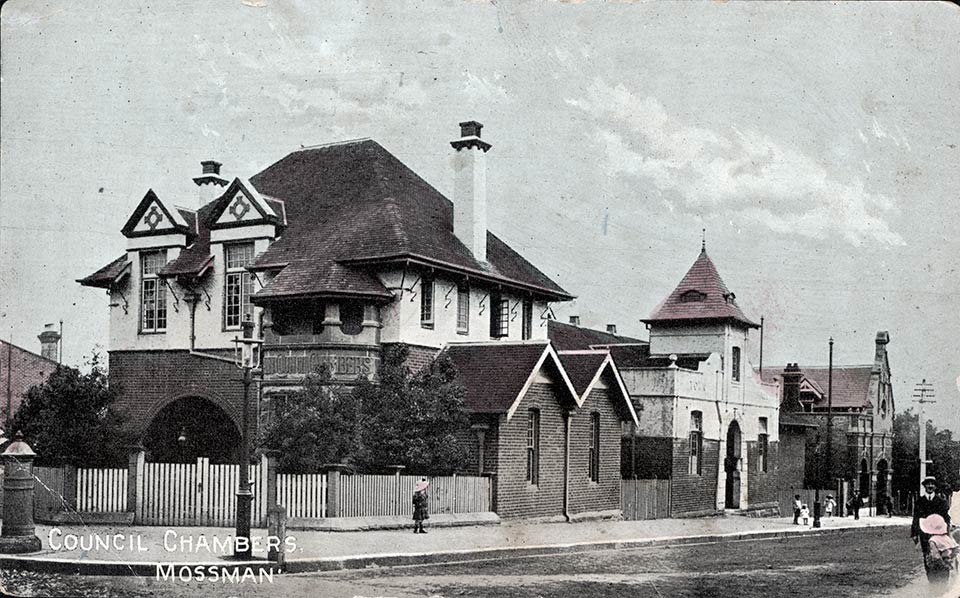

Mosman’s first council chambers at Spit Junction. Image: Mosman Library

Mosman’s first council chambers at Spit Junction. Image: Mosman Library

The pro-conscription Sydney Morning Herald reported on 28 September 1916 that Mosman Council’s support for the Prime Minister’s campaign:

A letter received by Mosman Council from the Prime Minister Mr W.M. Hughes asked the Mayor to convene a public meeting to establish a strong committee, with a view of bringing to a successful issue the referendum proposals. The council agreed to the Prime Minister’s request, and a meeting will be called … to be held next Friday night at the Protestant Hall, at 8 o’clock, for the purpose of taking a vote by ballot on the question of conscription.15

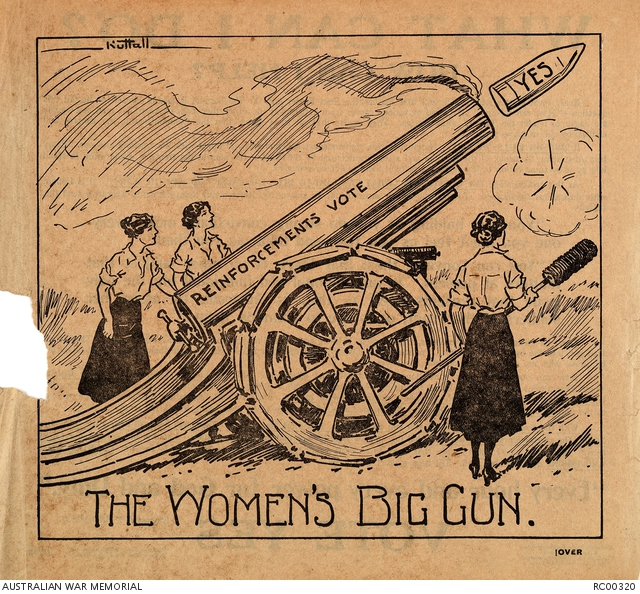

Mosman women stand by Hughes

Conservative women’s organizations actively supported Billy Hughes’ crusade:

On October 10 The Sydney Morning Herald reported16

A largely-attended meeting of women, presided over by Mrs. Stanhope Swift (president of the Mosman-Neutral Bay Reform League) was held in the Mosman Town Hall last night.

Mrs. Swift called upon her audience to realise that the successful carrying of the referendum cast upon the women a solemn duty, and they should take up their cross and bear it in the light of righteousness and freedom. The women should be up and doing, and show the anti-conscriptionists that they at least would not allow their noble heroes at the front to languish for the want of support. (Applause)

Miss Collison, B.A, of the women’s committee of the State National Referendum Campaign then spoke. Ms Collision believed women had an “unprecedented responsibility … as voting citizens of the Commonwealth with equal rights” to support compulsory enlistment. She continued:

If they [women] believed in the preservation of life they should see that sufficient reinforcements were sent to bring the war to a speedy conclusion. It was untrue to say that conscription was undemocratic. Those who objected to compulsion now did not scruple about compelling a man to join a Union. Did they get the privilege of an eight-hour day without compulsion? It required compulsion to have the minimum wage placed upon the statute book. Again, people did not pay taxes of their own sweet will.

They had had compulsion all along the line, and where was the logic of opposing it in a grave matter of this kind? (Applause).

Miss Collison concluded by moving:

That this meeting pledges itself to stand by Mr. Hughes in the action he has taken on conscription, and to work towards the triumphant carrying of the referendum.

The motion was seconded by Mrs. Burton and ‘carried amidst cheers.’

Others vote NO:

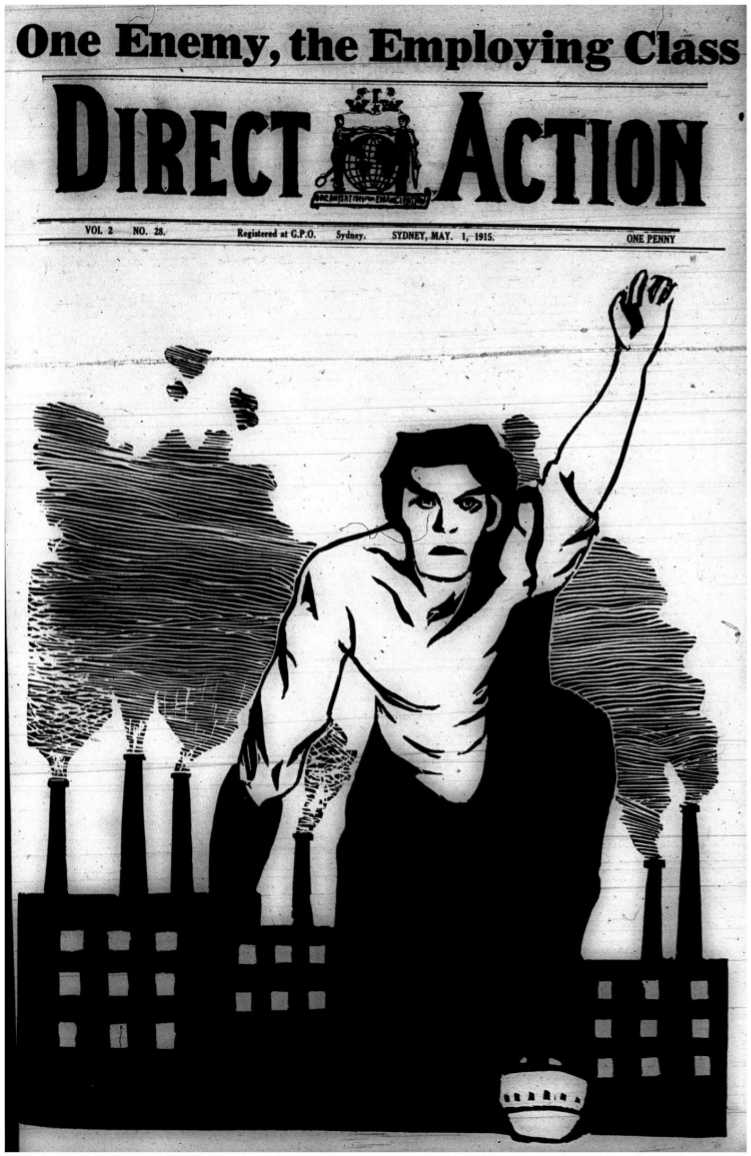

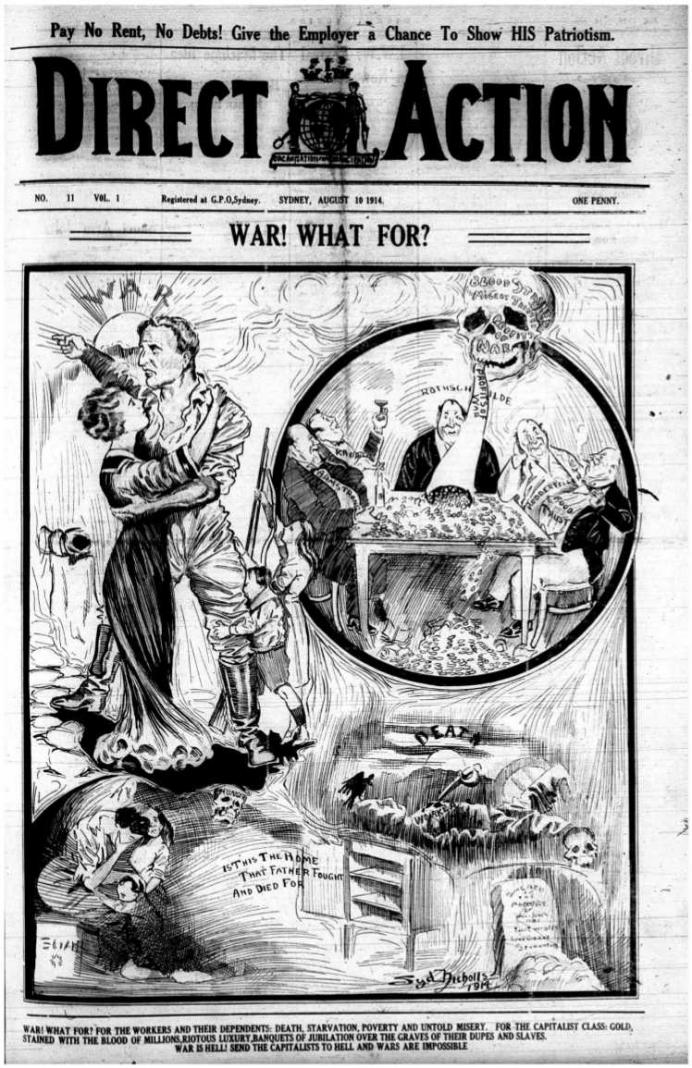

‘Direct Action’ Magazine front cover published by the Industrial Workers of the World Australian Administration

‘Direct Action’ Magazine front cover published by the Industrial Workers of the World Australian Administration

Knuckles, boots and curses

Ms Collison was preaching to the converted. Her arguments at the Mosman Town Hall wouldn’t have gone down well with NO voters. The compulsion to pay taxes and join Unions did not result in disability, death, devastation of families or entire communities. In Melbourne, when women speakers for the pro-conscription ‘National Referendum Council’ left their meeting they were pelted with mud by factory workers.

Pro conscription meetings in other parts of the country were disrupted in different ways. Hecklers drowned out speakers and invaded podiums. Pro-conscription supporters threw rotten eggs17 and broke banners during demonstrations that were described by The Age :

a parade of women promoted by the United Women’s No-Conscription Committee – an immense crowd of about 60,000 people… a surging area of humanity”.18

Some demonstrations got out of hand. In Brisbane servicemen forming a military picket broke ranks and attacked the crowd. The ‘NO’ rally reportedly degenerated into a “free fight of knuckles and boots, riding whips and curses.”19 1 person was shot with each side blaming the other for the violence.

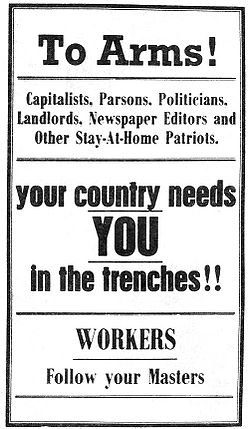

Workers follow your Masters

Socialists had the answer to ending the war: if the privileged (who advocated conscription) were so enthusiastic, let them go and die in the mud!

‘Direct Action’ Magazine front cover published by the Industrial Workers of the World Australian Administration

‘Direct Action’ Magazine front cover published by the Industrial Workers of the World Australian Administration