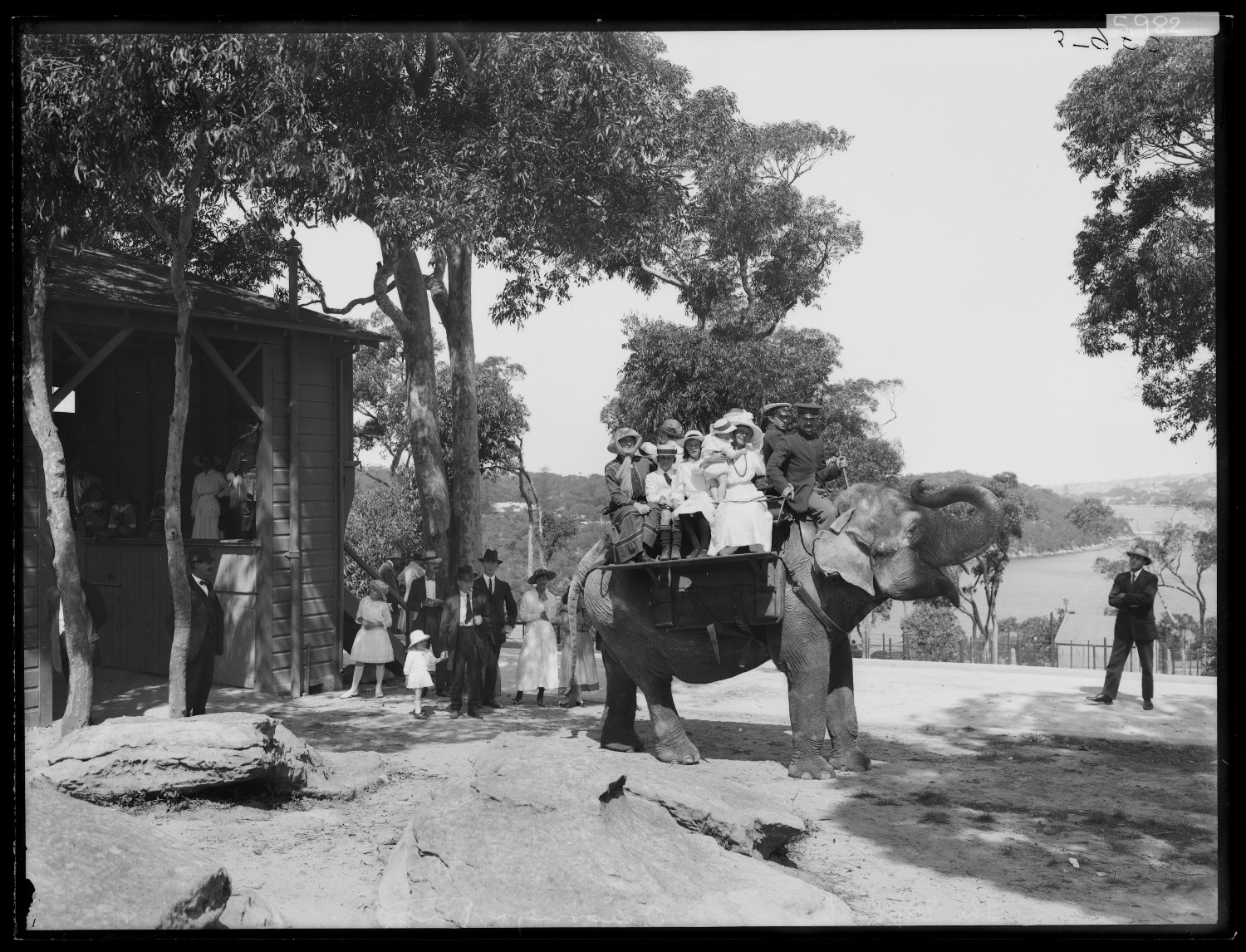

Photographs of strike-breakers at Taronga Zoo and a digitised image of a letter written by a Mosman mother enquiring about her son, give us a glimpse into Australian society in the early 20th century.

Society in crisis: 1916/17

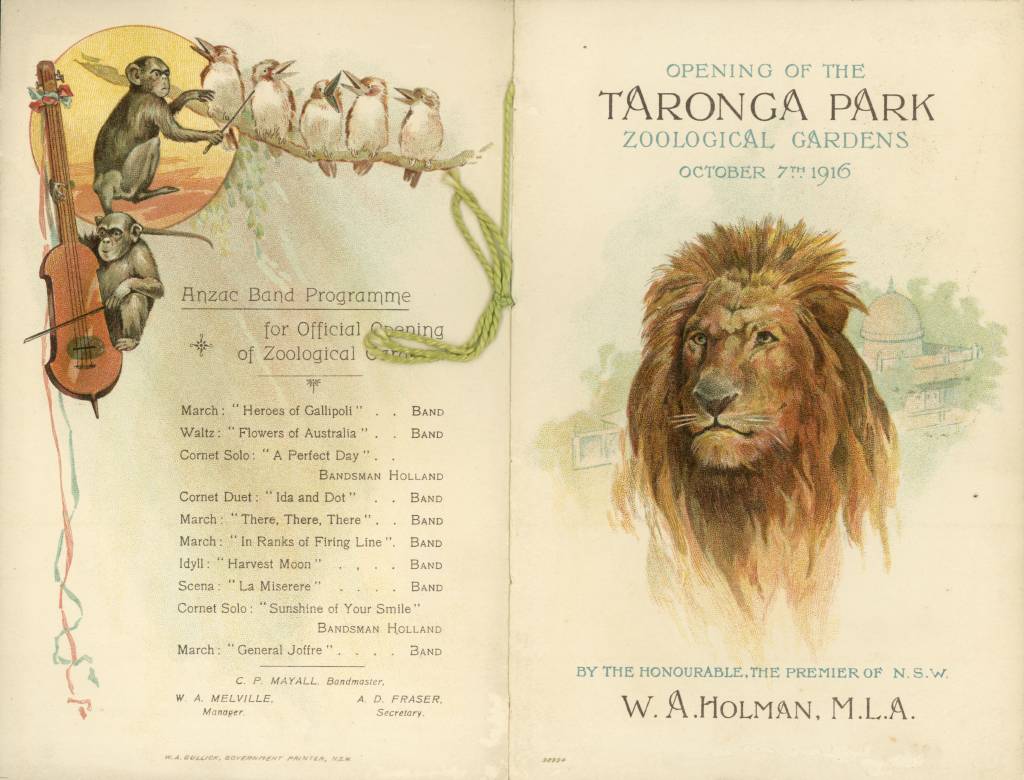

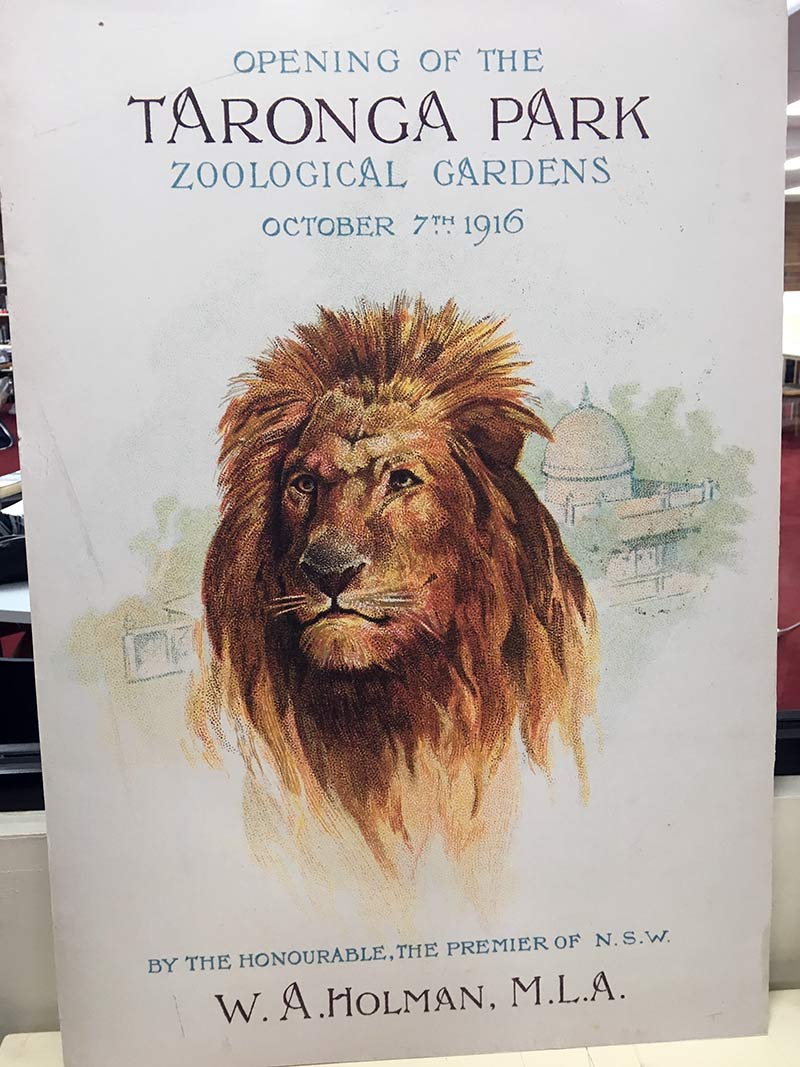

Opening of Taronga Zoo, 7 October 1916

Opening of Taronga Zoo, 7 October 1916

Opening invitation, 7 October 1916

Opening invitation, 7 October 1916

La Miserere: an opening programme, a mothers grief

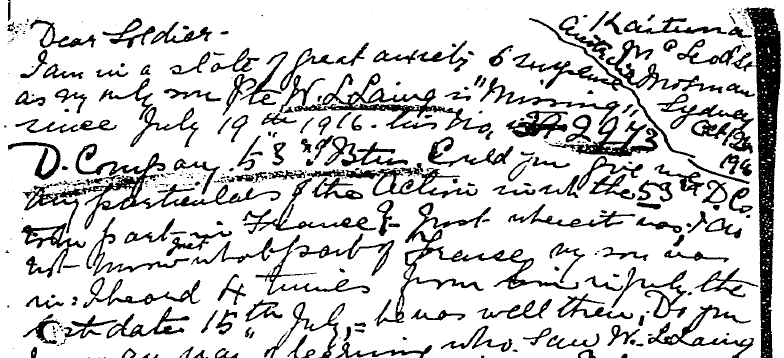

Following the Battle of Fromelles the Laing household of “Kaituna” in McLeod Street, Mosman, were told their only son William Laing was missing. After months without news, his mother Sarah wrote two days after the Zoo opening in a state of great anxiety and suspense:

October 9th, 1916

Dear Sir

I am in a cruel state of suspense about my son – No. 2973 Pte. W. L. Laing D Company, 53rd Battalion. Officially reported “Missing” July 19th 1916, would it be possible to find out if he is a “Prisoner of War”? It would be such a relief to us to know if his life has been spared …

When my son wrote last on July 15th he appeared to be well and happy … We had four letters and postcards in July. He was a most kind and considerate son and always wrote so that we would not worry. Would it be possible for us to know which engagement [he] took part in on July 19th? We do not know what part of France D Company 53rd Battalion was in on that date.

Her letter is one of thousands of digitised files with the Australian Red Cross Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau. It was written on the back of a pamphlet for the opening of Taronga Park Zoological Gardens on 07/08/1916.

Sarah Laing’s letter asking after her son (AWM R149302)

Sarah Laing’s letter asking after her son (AWM R149302)

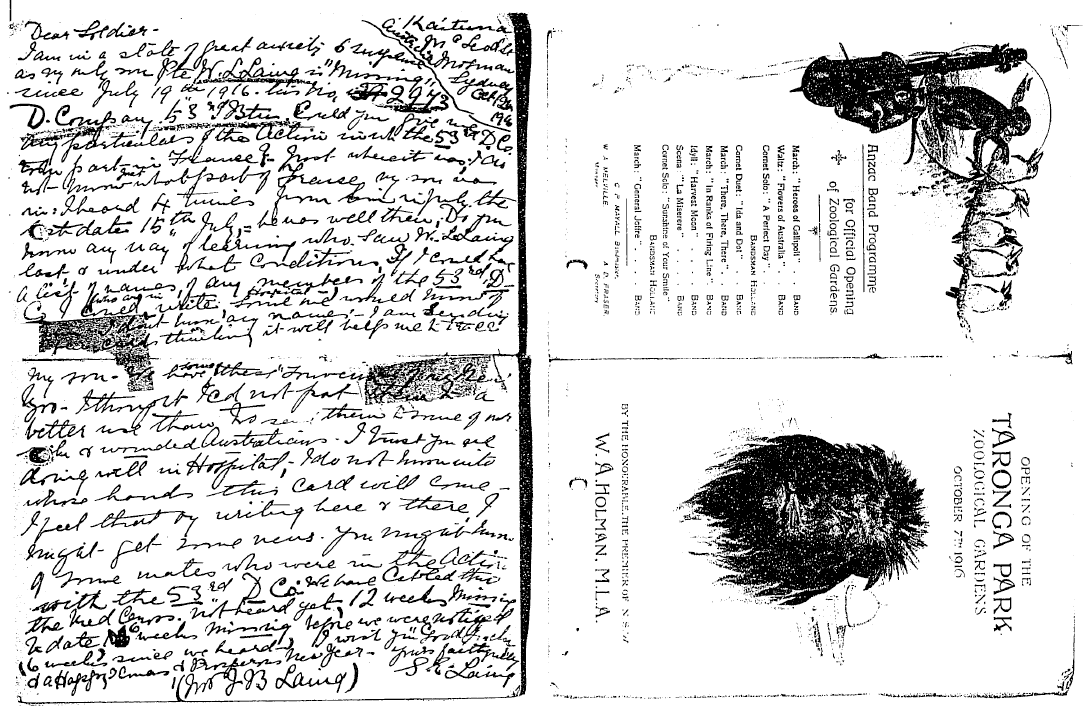

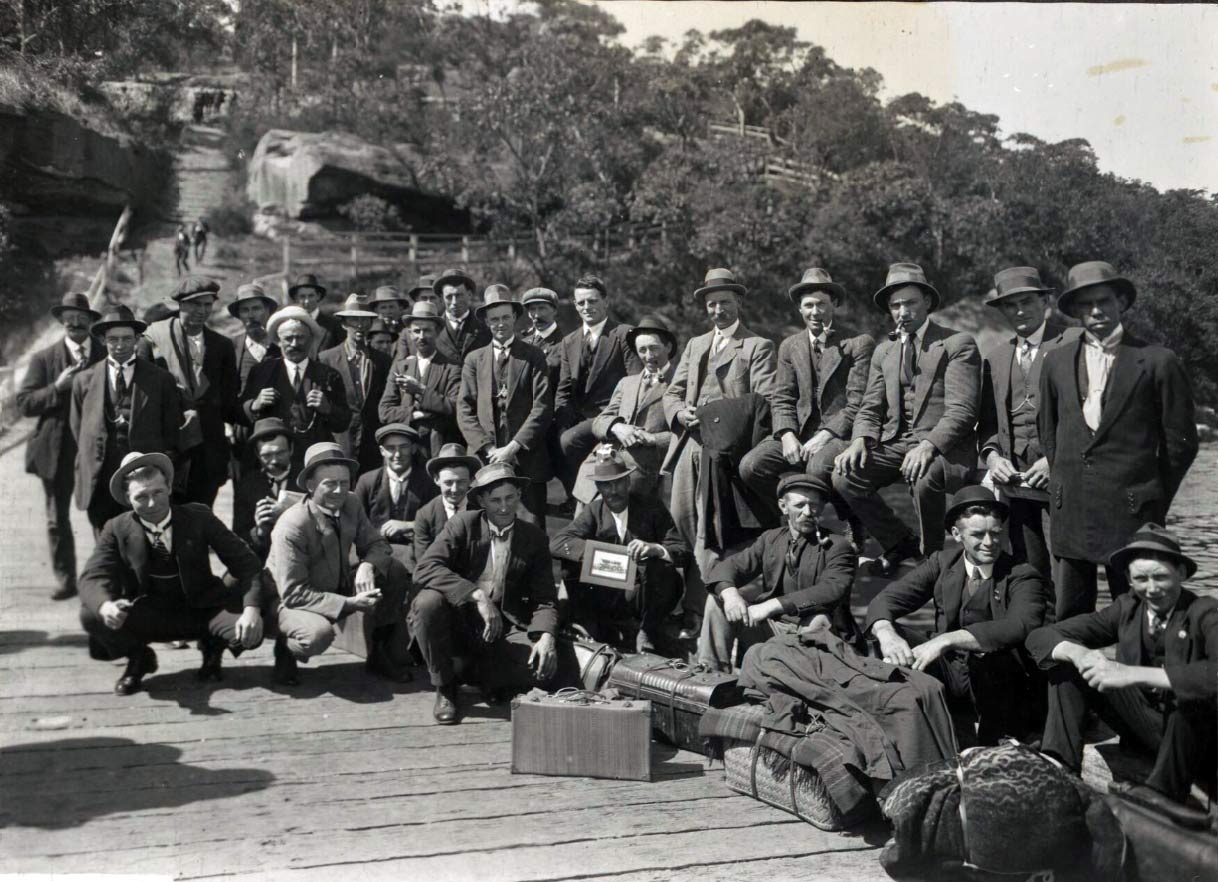

Taronga’s other inhabitants

Strike-breakers on Taronga Wharf, 1917. Stanley R. Beer Studio (National Library of Australia)

Strike-breakers on Taronga Wharf, 1917. Stanley R. Beer Studio (National Library of Australia)

By 1917 the nation was divided. Casualty lists, Conscription and falling living standards were a hazardous mix. In August industrial unrest exploded and spread nation-wide.

In 1917, Taronga Zoo’s grounds became a campsite for strike-breakers.

A former employee of the zoo recalled:

The Government took over the new Zoo area as a camp for free labourers. At one stage 1000 men were living there under canvas. For three months the gates were closed to the public, nil costs of upkeep with salaries being paid by the Government.1

These ‘free labourers’ were also known as volunteers or ‘loyalists’. The 100,000 striking workers across eastern Australia had plenty of other names for them.

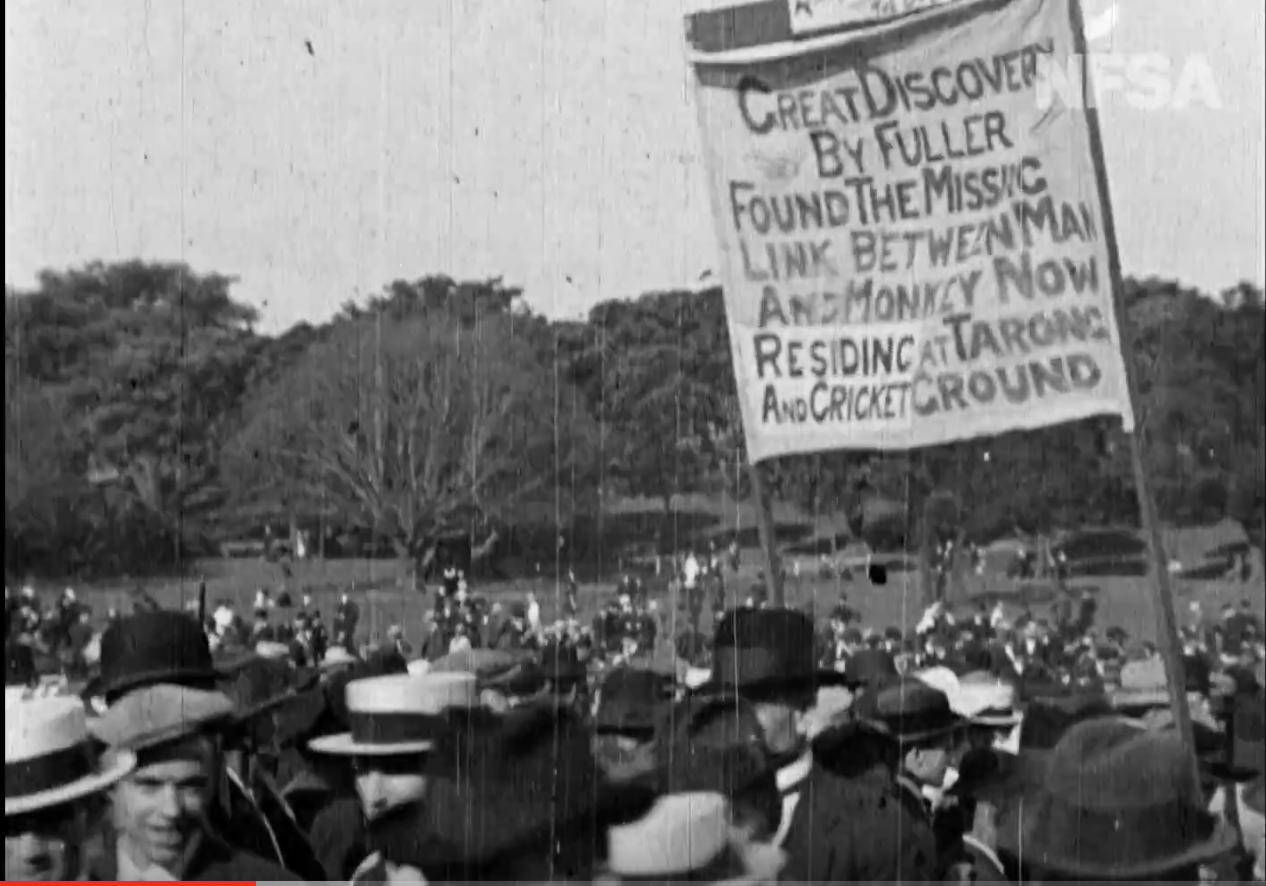

Screen shot of 1917 film reconstructed by National Film & Sound Archive experts https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/australias-great-strike-100-years. The placards protest or make humorous reference to strike breakers residing at Taronga Zoo.

Screen shot of 1917 film reconstructed by National Film & Sound Archive experts https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/australias-great-strike-100-years. The placards protest or make humorous reference to strike breakers residing at Taronga Zoo.

The strikebreakers were recruited mainly from country areas and were used to fill jobs on the wharves or in essential industries. Teachers and students from Shore, Newington and Sydney University ‘had the time of their lives’ volunteering to keep trains and trams running from Central station.

Schoolboy strikebreakers with a steam train during the 1917 strike. Picture: State Library of NSW.

Schoolboy strikebreakers with a steam train during the 1917 strike. Picture: State Library of NSW.

One of the SCEG’s schoolboys was Adrian Curlewis. He lived with his parents on the ‘other side of the tracks’ at Mosman. His Father Herbert Raine Curlewis (b.1869) had married Ethel Turner, author of Seven Little Australians , in 1896.

According to the Ethel Curlewis’ (nee. Turner’s) biographer Brenda Niall

The marriage was happy: each fostered the other’s career. They rented a cottage at Mosman until their own house, Avenel, overlooking Middle Harbour, was completed in 1903. Their daughter was born in 1898 and their son in 1901.

Ethel Curlewis in the lower garden at Avenel. Source: ‘Trace’ digital image archive, Barry O’Keefe Library.

Ethel Curlewis in the lower garden at Avenel. Source: ‘Trace’ digital image archive, Barry O’Keefe Library.

During World War I Ethel Turner organized ambulance and first aid courses, campaigned for conscription and worked for patriotic causes. With Bertram Stevens, she edited The Australian Soldiers’ Gift Book (1917). She also embarked on a temperance crusade in St. Tom and the Dragon (1918). A wartime trilogy—The Cub (1915), Captain Cub (1917) and Brigid and the Cub (1919)—is notable for its freedom from anti-German hysteria and for its sympathetic portrayal of a reluctant Anzac; the ideal of loyalty to Empire is combined with a strong sense of Australian nationalism.2

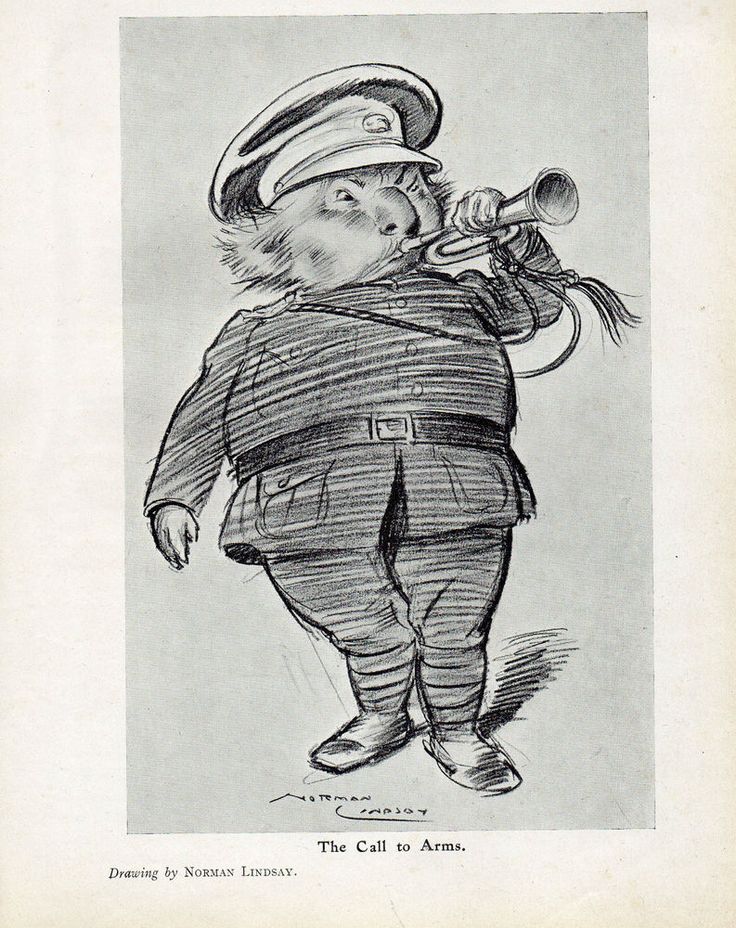

‘Call to arms’ patriotic Illustration by Norman Lindsay for the “Australian Soldiers’ Gift Book.”

‘Call to arms’ patriotic Illustration by Norman Lindsay for the “Australian Soldiers’ Gift Book.”

Ethel kept a diary. The entry for August 11th, 1917 reads:

Adrian volunteered- without his father’s permission, as a locomotive cleaner; a number of schoolboys took strikers’ places at Everleigh. He had a long, long day; up at 4.30 am walked to boat, walked from Quay, worked all day, walked back, from Lavender Bay. To a dance at Dr Retallack’s at night – and walked home!

She adds,

H. will not let him go – must remain neutral.3

S.C.E.G.S. pupils cleaning engines during the 1917 rail strike at Eveleigh (SLNSW)

S.C.E.G.S. pupils cleaning engines during the 1917 rail strike at Eveleigh (SLNSW)

Herbert Curlewis had recently been appointed Judge of the Industrial Arbitration Court. Adrian’s activities could potentially cause complications as it created a perception of bias, or showed personal political leanings. Judges of the time tended to be pillars of the establishment. They came down harshly on anyone involved or associated with, activities they viewed as undermining the social order. The IWW was declared an illegal organisation in 1916 and the Unions were de-registered in 1917.

Incitement to strike or hinder the transport of goods was sufficient for a jail term. Judges were very ready to sentence men to jail and could be swayed, as Judge Scholes was in April 1917 if the defendant displayed ‘a certain amount of impudence’ in what he was alleged to have said. Membership could create all manner of trouble. When one Roy Darcy was found with an IWW membership pay card he tried to explain to the magistrate that he must have joined when he was drunk and had no sympathy with the IWW movement. He had already been found guilty of using the words “scab” and “mongrel” to a tram guard. He was imprisoned with hard labour for three months.4

Screen shot of 1917 film reconstructed by National Film & Sound Archive experts https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/australias-great-strike-100-years. The placards protest or make humorous reference to strike breakers residing at Taronga Zoo.

Screen shot of 1917 film reconstructed by National Film & Sound Archive experts https://www.nfsa.gov.au/latest/australias-great-strike-100-years. The placards protest or make humorous reference to strike breakers residing at Taronga Zoo.

A light on the hill

The 1917 strike began when railway workers at Everleigh workshops walked off the job following years of diminishing wages and conditions. The introduction of a card system to monitor productivity was the final straw.

As part of the new workplace systems, foremen began watching over labourers, counting the time it took them to do certain tasks. The strikers called it “Americanising work” or “Robotism”. The managers, “scientific management”.

Workers believed the new system was turning them into machines, de-skilling them and destroying their collective bonds.5

Future Labour leaders Prime Minister Ben Chifley, working as an engine driver, and NSW premier Joseph Cahill, were both ‘laid off’ for taking part in the strike.

The strike-breakers photographed at Taronga were being used to break the resolve of men such as Ben Chifley. But it had the opposite effect. Chifley’s outlook was forged in the fires of adversity.

I should not be a member of this Parliament today if some tolerance had been extended to the men who took part in the strike of 1917. All that harsh and oppressive treatment did, as far as I was concerned was to transform me, with the assistance of my colleagues, from an ordinary engine-driver into the Prime Minister of this country.

Old Erecting Shop. Eveleigh Workshops during the 1917 railway strike (State Records NSW)

Old Erecting Shop. Eveleigh Workshops during the 1917 railway strike (State Records NSW)

I try to think of the Labour movement not as putting an extra sixpence into somebody’s pocket or making somebody Prime Minister or Premier, but as a movement bringing something better to the people, better standards of living, greater happiness to the mass of the people. We have a great objective - the light on the hill - which we aim to reach by working for the betterment of mankind not only here but anywhere we may give a helping hand. If it were not for that, the Labour movement would not be worth fighting for…

— Ben Chifley, Engineman NSW Govt. Railways 1902 -1928, Prime Minister of Australia 1945 -1949

Ben Chifley’s philosophy and speeches resonated with future leaders and generations.

Sacrifice and Justice.

Evatt (left) and Ben Chifley (middle) with Clement Attlee (right) at the Dominion and British Leaders Conference, London, 1946

Amongst them was H V Evatt who like the Curlewis family would later reside ‘on the other side of the tracks’, in Mosman. Evatt’s philosophy and future career was inspired by men like Chifley and driven by the same pain suffered by many families at the time.

‘Bert’ Evatt had originally supported conscription as a Law student at Sydney Uni. but turned against the idea as the war dragged on, especially as he and his family were directly affected.

His 2 younger brothers Raymond Scott and Septimus Francis had signed up in 1915 and 1916. ‘Ray’ was the adventurous outdoor type, keen to enlist. He had survived Gallipoli and been promoted to lieutenant. ‘Frank’ was a sensitive and bookish medical student. He spent his time recovering from wounds in London by going to the opera and musical concerts.6

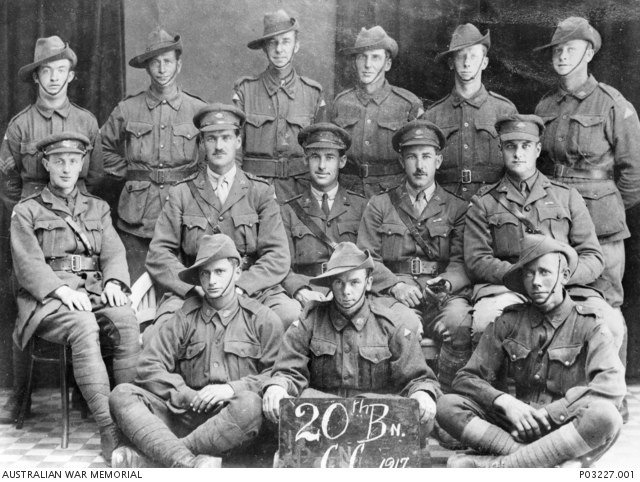

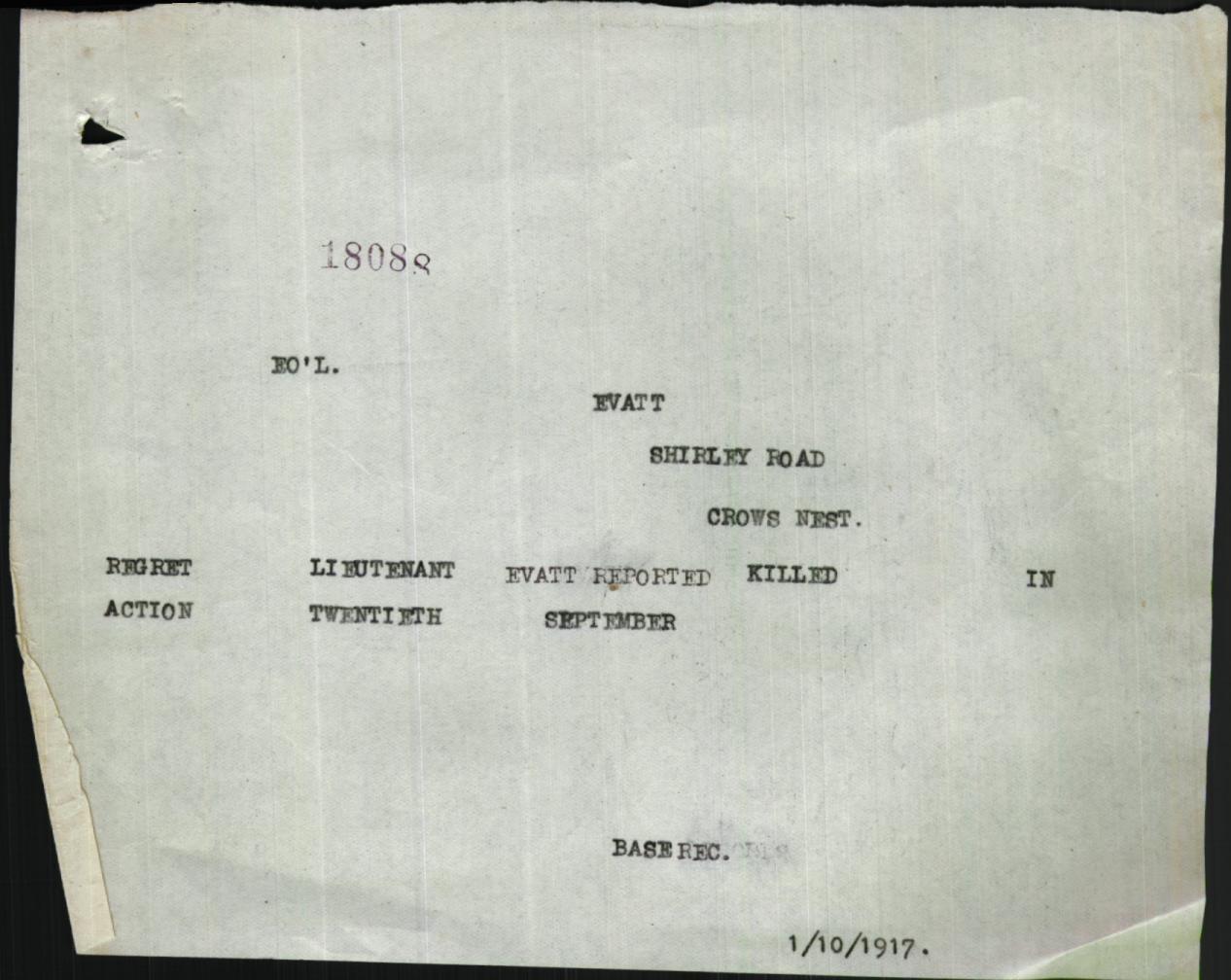

Frank looked up to, and wished to emulate Ray, a soldier’s soldier. Ray had been wounded 3 times and was awarded the Military Cross for bravery. On one occasion he had stayed in his trench and fought on despite being wounded. His medical files describe a gun-shot wound exiting his right arm as ‘large and ragged.’ It was a great shock to the family when Ray was killed near Ypres on 20/09/1917. Unfortunately, like many soldiers, his remains could not be located.

Group portrait of the 20th Battalion Cricket team which won the 5th Brigade Cricket Competition. Second row: Lieutenant (Lt) McMillan; Captain Barlow, Major Hailes; Lt Hall MC; Lt Evatt MC. Source: AWM

Group portrait of the 20th Battalion Cricket team which won the 5th Brigade Cricket Competition. Second row: Lieutenant (Lt) McMillan; Captain Barlow, Major Hailes; Lt Hall MC; Lt Evatt MC. Source: AWM

Telegram confirming the death of HV Evatt’s brother Ray. Source: National Australian Archives; Digitised service record of Raymond Scott EVATT. The family had various residences during the war: 8 Grantham Rd, Milsons Point; ‘Ellimo’, Shirley Rd., Wollstonecraft; “Avonlea” Murdoch St., Cremorne; and “Berowra” 64 Carrabella St., Milsons Point.

Telegram confirming the death of HV Evatt’s brother Ray. Source: National Australian Archives; Digitised service record of Raymond Scott EVATT. The family had various residences during the war: 8 Grantham Rd, Milsons Point; ‘Ellimo’, Shirley Rd., Wollstonecraft; “Avonlea” Murdoch St., Cremorne; and “Berowra” 64 Carrabella St., Milsons Point.

Bert tried unsuccessfully to have Frank (who was convalescing in England after being wounded) sent home4. A few weeks before the war ended Frank died. His records record shrapnel wounds to the chest on 29/09/18 near Rouen. Frank’s effects were sent home. They included a pipe, photos, letters and a ‘Book of Verse.’ Septimus Francis Evatt is buried at Tincourt Cemetery, France.

Both brothers are also remembered in a memorial plaque at the family church; St Johns, Milsons Point, North Sydney and at the AWM.

Jeanie Evatt was understandably devastated at the loss of two sons; she shared the grief pervading Australian society. The story in the family was that she never recovered from the loss of Ray and Frank.7

Years later Bert Evatt wrote a biography of the pro-conscription N.S.W. State Premier W.A. Holman, he observed that

Holman failed to realize the tremendous strain and anxiety in every family from which a member was absent at the front. The burden was far greater than that of any politician. It was almost too heavy to be bourne.8

It was the anxiety and loss of loved ones that so influenced the Conscription referendum debates of 1916 and 1917.

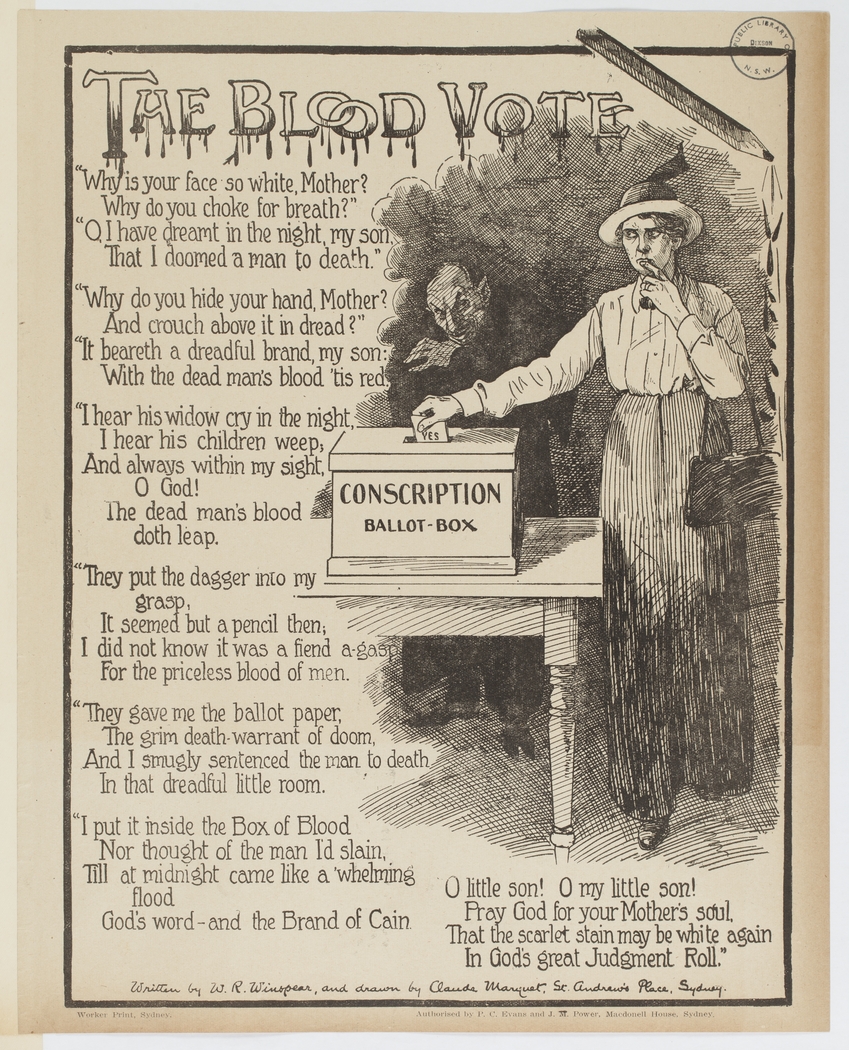

Leaflet bearing a verse by W.R. Winspear and a cartoon by Claude Marquet, featuring an image a deeply worried woman casting a ‘Yes’ vote while Billy Hughes, Australia’s labor prime minister and supporter of conscription, looks on gleefully. It was printed by Fraser & Jenkinson in Melbourne, 1917 and authorised by J. Curtin, Secretary for the ‘National Executive’. Source: ‘Trove’, NLA.

Leaflet bearing a verse by W.R. Winspear and a cartoon by Claude Marquet, featuring an image a deeply worried woman casting a ‘Yes’ vote while Billy Hughes, Australia’s labor prime minister and supporter of conscription, looks on gleefully. It was printed by Fraser & Jenkinson in Melbourne, 1917 and authorised by J. Curtin, Secretary for the ‘National Executive’. Source: ‘Trove’, NLA.

By 1920, Bert Evatt was assisting with the Royal Commission into the victimization of the 1917 transport strikers. He was Junior Counsel for the State government in the Engineers’ case, where he “encountered the successful rivalry of Robert Menzies in the High Court of Australia.”9

Whilst his legal career was taking off his political career had humble beginnings. In 1920 he joined the Mosman Political Labour League. Founded in February 1920, the branch started with a handful of members, rising to 10 after Evatt’s membership acceptance on the 30th of April. Biographer John Murphy in Evatt: A life notes that

Among Evatt’s papers is the tattered exercise book recording the first 2 years of the Mosman branch. It shows that Evatt was a distinctly inactive member…10

Evatt resigned in 1925. As reported in the The Labor Daily justice for the 1917 strikers was an ongoing concern.

At the fortnightly meeting of the Mosman branch, Dr. Evatt tendered his resignation… Dr. Evatt spoke at some length. He was given an ovation. In an extremely interesting address, he narrated the story of the elections in Balmain. He sincerely thanked members of the branch for their courteous co-operation with him during his four years association with the league. Dr. Evatt said that the problem of unemployment should be dealt with in a practical manner, and as speedily as possible. The victimized men of 1917 must be given justice….

1920 was a busy year for Bert. He married Mary Alice Sheffer on the 27th of November. The couple moved into 1 Methuen Street, just up the road from the Zoo. They lived there until 1964.11

Evatt at his home in Mosman

The age of extremes: 1920s and 30s

Spoiling the party – New Guards inside fortress Mosman

Historian Gavin Souter notes:

The Australian Labour Party first contested an electorate containing Mosman in 1910, when its candidate won half as many votes as the successful Liberal in the Federal seat of North Sydney. During the next quarter of a century Labour contested North Sydney and Warringah five times, with its share of the vote dropping each time, from 30 percent in 1913 to 16 percent in 1934. The Federal seat of Warringah and the State seat of Mosman were and would remain UAP (and later Liberal Party) strongholds.12

During the ’14-18 War Mosman’s voters supported Billy Hughes’ crusade for conscription. After the 1914-18 war ended, extreme political ideologies gained ground.

The Old Guard was a secretive, militaristic organisation post 1918. It had a strong presence in the Mosman borough. In 1932 Mayor, Cyril Camplin, and at least 2 other aldermen (including Wallace Fyfe Henderson and Eric Clegg) were members.

New Guard Captain Francis de Groot dramatically upstaged the Labour Premier Jack Lang at the Sydney Harbour Bridge opening. He cut the ceremonial ribbon with his sword on horseback.

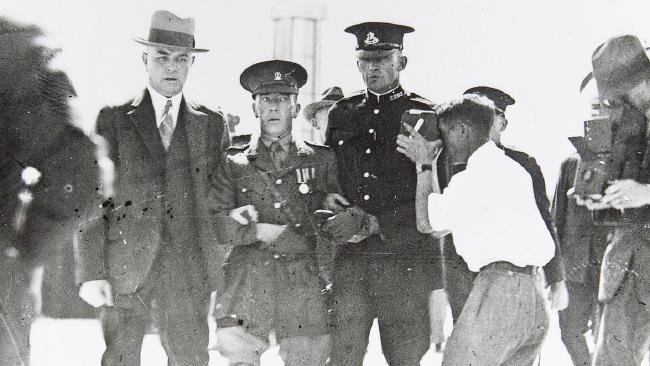

De Groot cuts the ribbon at the Sydney Harbour Bridge opening ceremony, 19 March 1932

De Groot cuts the ribbon at the Sydney Harbour Bridge opening ceremony, 19 March 1932

It was the subject of heated discussion by Mosman councillors [although] there was no difference of opinion as to the Bridge’s great benefit to Mosman13

Alderman Frank Pursell moved, and Alderman Leon Stevenson seconded, the following motion on the 22nd of March, 1932. It was carried 7-5 with the support of the New Guard Councillors and the Mayor

That this Council, representing the citizens of Mosman, emphatically protests to the Chief Secretary against the travesty of British Justice in the action of the Commissioner of Police or his officers responsible for the detention of Captain De Groot … This council, while not expressing an opinion on the rights or wrongs of Captain De Groot’s action, views with alarm the unprecedented steps taken by the police, which savour of biased political vindictiveness undermining the liberty of the subject and bringing the integrity and good name of the police into question.14

De Groot arrested, 19 March 1932

De Groot arrested, 19 March 1932

In 1932, ‘New Guard’ Commander, and occasional Fascist Eric Campbell crushed any internal opposition. He then held a meeting at the Mosman Town Hall. The venue was packed out. Those who could not fit inside got ladders to look through upper windows. Many of the 600 enthusiastic supporters, reportedly, became new recruits15

Eric Campbell leads a New Guard rally in a fascist salute, 18 February 1932 at Sydney Town hall

Alternative views still existed in the area despite Eric Campbell’s shadowy army.

Mosman as yet had no branch of the Australian Communist Party, although a few members of that Party and the Movement Against War and Fascism met in Private Mosman homes from the mid-1930’s onward.16

Cold War: post-1950

Principles upheld: another referendum defeated

Emnity, suspicion and open hostility between left and right continued erupted after the ’39-‘45 The Cold War era brought new tensions.

The Hon. Michael Kirby (AC, CMG) recalled in a speech given at Sydney University — The Declaration of Human Rights, H.V. Evatt and Liberty in Australia — how he had viewed ASIO files kept on his step-grandfather Jack Simpson. Simpson was considered by the State to be another “Red under the bed”

In recent years, I have read extracts from Jack Simpson’s national security file. One such entry in 1950 records how he was closely observed at the Sydney Taronga Park Zoo, in company with three young schoolchildren. Perhaps those conducting the surveillance were concerned about the potential communist corruption of young minds. If so, they need not have been concerned. One of those schoolboys became a leading Sydney solicitor. Another is now a judge of the Supreme Court of New South Wales. And the eldest was myself.17

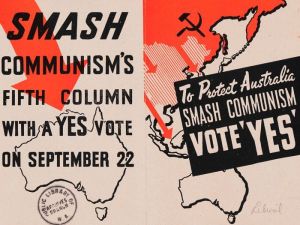

Evatt was instrumental in blocking the Menzies government’s attempts to ban Communist parties in the High Court. The issue was put to the people in a referendum (which failed) in 1951.

After Hungary in 1956, Jack Simpson came to question his political philosophy. But he was idealistic if misguided. And Australia’s highest Court and then the electors, upheld the principle that he was entitled to his political opinions, however misguided they might seem to be.18

The conscription debate re-visits Mosman

In the same year Taronga Zoo was opened and Australia had its first conscription referendum, future Australian PM Gough Whitlam was born. After moving to Sydney, his family lived in Mosman.

In 1966, following the Chifley and Evatt governments, Whitlam became Deputy to Labour leader Arthur Calwell .

Gough Whitlam and Arthur Calwell in 1960, the year they took over as Leader and Deputy Leader of the Australian Labor Party (NAA: M155, B2)

Gough Whitlam and Arthur Calwell in 1960, the year they took over as Leader and Deputy Leader of the Australian Labor Party (NAA: M155, B2)

That year Calwell spoke at a Vietnam anti-conscription rally at the Mosman Town Hall. As he left the meeting, Peter Kocan fired into the window of Calwell’s car. Luckily the bullet deflected, and Calwell incurred only minor facial injuries. He was patched up at Royal North Shore Hospital and released the next day. Calwell later Kocan in prison, and forgave him.

Sydney Morning Herald

Sydney Morning Herald

After narrowly losing the 1969 election, Whitlam went on to win in 1972. A number one reform for the Whitlam government was to ban military conscription. Military service through the unpopular birthday ballot could no longer be enforced. The Australian armed forces have been recruited on a voluntary and professional basis ever since.

Taronga Zoo: 2016

With the exception of 3 months in 1917 when it was closed to house the strike-breakers, Taronga has remained open to a fascinated public for 100 years.

The zoo in February 1917

The zoo in February 1917

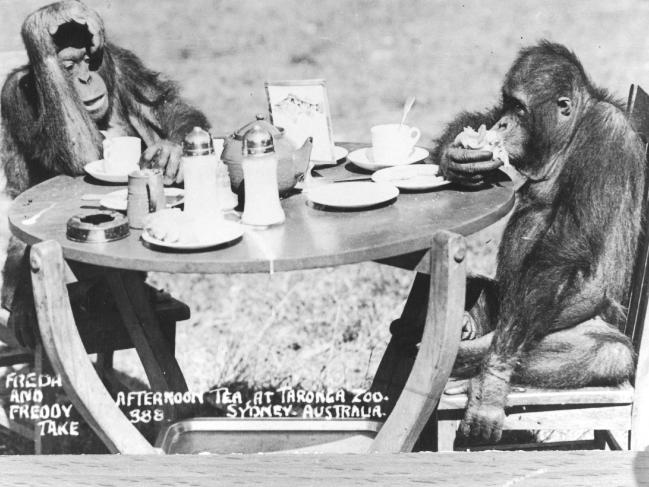

We can visit the monkey enclosure as many generations have, and wonder at our similarities and differences, reflected in the simian faces.

Humans have the capacity to form sophisticated societies To produce, consume and redistribute wealth. To house and provide education and health care. To use the highest potential of our minds to create, or to engage in organized warfare and destroy ourselves.

The human political zoo continues on in all its variety. The tussle between labour and capital — for control over the means of production to create a fair and free society — is set to continue for some time yet.

Freda and Freddy take afternoon tea at Taronga Zoo

Freda and Freddy take afternoon tea at Taronga Zoo

The program for Taronga Zoo’s opening, on display at Barry O’Keefe Library

Display for the 100th anniversary of the Zoo opening. Source: Trace image collection Barry O’Keefe Library via Donna Braye, Local Studies Librarian.

Display for the 100th anniversary of the Zoo opening. Source: Trace image collection Barry O’Keefe Library via Donna Braye, Local Studies Librarian.