Top Imperial German Army sign board, taken from the roadside leading into Fromelles, opposite the trenches occupied by the 5th Australian Division. Photo taken by Author at ‘Spirit of ANZAC’ traveling exhibition, April 2017. Below:Men of the 53rd Battalion waiting to don their equipment for the attack at Fromelles. Only three of these men came out of the action alive, and all three were wounded. Image: AWM A03042

Top Imperial German Army sign board, taken from the roadside leading into Fromelles, opposite the trenches occupied by the 5th Australian Division. Photo taken by Author at ‘Spirit of ANZAC’ traveling exhibition, April 2017. Below:Men of the 53rd Battalion waiting to don their equipment for the attack at Fromelles. Only three of these men came out of the action alive, and all three were wounded. Image: AWM A03042

The 53rd Battalion at Fromelles

The 53rd Battalion, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Ignatius Bertram Norris, formed in Egypt. It was a mix of Gallipoli veterans and new recruits from Australia. The 53rd Btn. was assigned to the 14th (NSW) Brigade of the 5th Australian Division. It shipped to France in June 1916.11

The Wilson brothers: Eric, Samuel and James. Images: AWM P05445.002, P05445.001, P05445.003

The Wilson brothers: Eric, Samuel and James. Images: AWM P05445.002, P05445.001, P05445.003

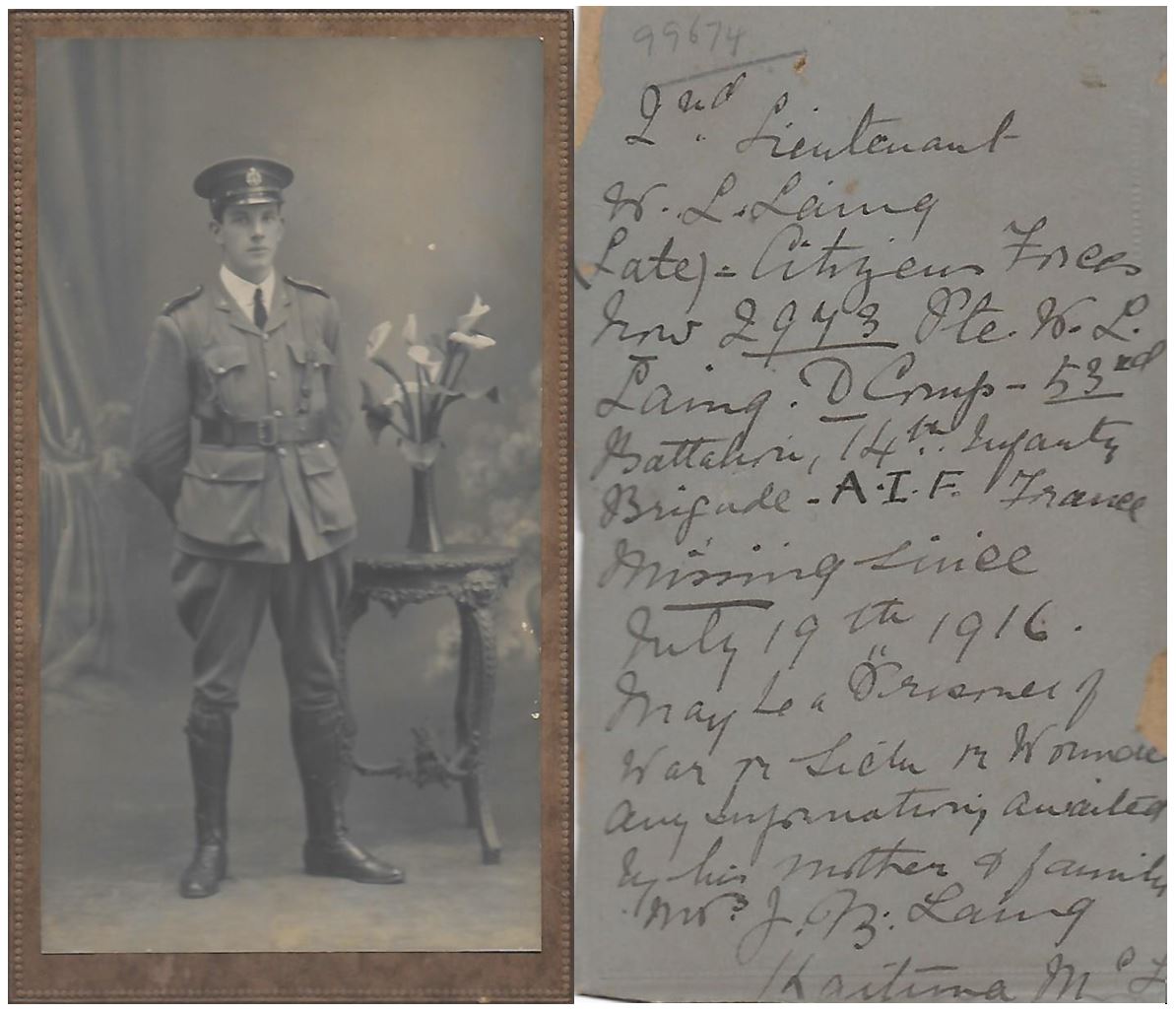

William L Laing

William L Laing

In its ranks were three Mosman brothers; Eric (29), Samuel (20) and James Wilson (18). Their mother, Isabella, lived at “Myall” on Wolseley Road. They worked at their father’s (George Wilson’s) timber mill at Port Macquarie.

Another local was William Laing a clerk aged 22. Parents John and Sarah Laing, lived at “Kaituna” in McLeod Street.

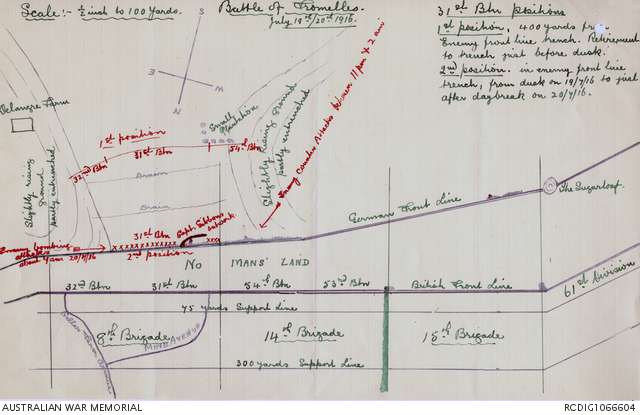

On the evening of the 19th of July, 1916, the 14th Brigade formed up with 15th (Victorian) Brigade on its right, and the 8th to its left. 54 and 53 Battalion faced the German lines with the 55th in support. To the 53rd’s right was 59 Btn. (from 15th Brigade).

AWM38 3DRL 606/243A/1 – 1916 – 1934. Official History, 1914-18 War: Records of C E W Bean, Official Historian.- AWM38 3DRL 606 – Diaries, Notebooks and Folders

AWM38 3DRL 606/243A/1 – 1916 – 1934. Official History, 1914-18 War: Records of C E W Bean, Official Historian.- AWM38 3DRL 606 – Diaries, Notebooks and Folders

The 53rd’s main objective was to take trenches to the left of an elevated German defensive position and link up with other units. Key to the attack’s success, the ‘Sugarloaf’ had to be taken. If not the 53rd would be subjected to murderous enfiled fire, and counter-attack from that direction.

6 pm: The attack begins

The preliminary artillery barrage was loud and impressive, but not always accurate. Reginald Hugh Knyvett later wrote in ‘Over There’ with the Australians:

…we soon began to discover that the shells that were bursting among us were many of them coming from behind…Our first message over the ‘phone was very polite. “We preferred to be killed by the Germans, thank you,” was all we said to the battery commander. But as his remarks continued to come to us through the air, accompanied by a charge of explosive, and two of our officers being killed, our next message was worded very differently, and we told him that “if he fired again we would turn the machine-guns on to them.” I was sent back to make sure that he got the message. I took the precaution to take back with me one of his “duds” (un-exploded shells) as evidence…

The results of atillery fire dropping behind redoubts

The results of atillery fire dropping behind redoubts

German counter-fire landed in clogged trenches, over troops moving over open ground, or through starting points. German survivors of the British artillery storm quickly reoccupied their trenches and vantage points looking over no man’s land.

15th Brigade was decimated in front of the Sugarloaf. Private Jimmy Downing of 57th Battalion wrote about the experience of running into the teeth of machine-gun fire:

The bullets skimmed low, from knee to groin, riddling the tumbling bodies before they touched the ground. Hundreds were mown down in the flicker of an eyelid…a valley of death filled by somebody’s blunder.

German machine gunners

German machine gunners

Hauptmann Hans Gebhardt, (Battalion commander of 11 Company 16 RIR) reported:

Having lifted their artillery barrage the English [British and Australian infantry] leapt over the parapet or left their trenches via masked exits. After initially leaving the trench they formed dense groups, then attempted to deploy in an attacking line. These [attacking] lines then proceeded to assault but failed to keep formation. The enemy tried four or five times to form such lines but were mostly shot down whilst still in groups and before they could organise.

Some of the Australians only left the trench hesitantly, and this is when their officers moved up with drawn revolvers and tried to move them forward. It then became obvious which were officers and these were shot down.

Some groups that began to withdrawn were encouraged to renew the attack by those still in the trenches; they quickly fell to our machine-gun and infantry fire like the others, if they had not already been cut down by our artillery. The enemy was obviously of the belief that our defences were so weak that they could be overcome, so when we opened fire they were completely taken by surprise and lost their heads. In a diary that we found, the entry for the 19th [July] reads: ‘We are now about to take the German trenches; we think this will be very easy.’6

Into the belly of the Wohngraben

19 July 1916. British trenches and breastworks are seen left, running top to bottom. The 31st and 32nd Battalions AIF attacked from here. German lines occupy the centre. Image: AWM J00278

19 July 1916. British trenches and breastworks are seen left, running top to bottom. The 31st and 32nd Battalions AIF attacked from here. German lines occupy the centre. Image: AWM J00278

Stained glass window donated by Norris family to St. Ignatius College Chapel, Riverview in 1931. Photo taken by the Author.

Stained glass window donated by Norris family to St. Ignatius College Chapel, Riverview in 1931. Photo taken by the Author.

The 14th Battalion had a slightly easier time than the 15th and made their first objectives. The German breastworks in front of them were taken by bayonet charge. The defenders were killed emerging fro their shelters, or driven off. The 53rd then moved on to the second line of defenses, a substantial trench system known as the Wohngraben.12

Lieut. Col. Norris and his staff were spotted moving over open ground toward the Wohngraben. Norris was cut down by fore from the Sugarloaf. The last reported words of the respected leader were ‘Here, I’m done, will somebody take my papers?’13

With officers dead or wounded, communication between units broke down. Lacking clear direction the men became disorientated. Groups disappeared into the dust and smoke became lost in the maze of trenches or wandered into ‘supporting’ artillery fire.

Some made it to their last objective, the third ‘trench-line’. They were dismayed to find waterlogged ditches and bogs, impossible to defend.

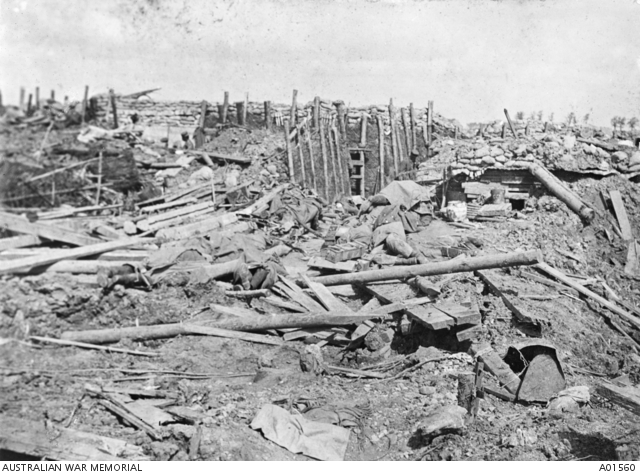

Portion of the German second line line held by the 31st Battalion AIF on the night of the battle. Note the attempt at consolidation. This photograph was taken during the morning of 20 July whilst the Germans were re-occupying their old position. Image: AWM A01562

Portion of the German second line line held by the 31st Battalion AIF on the night of the battle. Note the attempt at consolidation. This photograph was taken during the morning of 20 July whilst the Germans were re-occupying their old position. Image: AWM A01562

By 7 pm the Germans countered. Despite constant pressure, the 53rd were able to maintain their positions until late in the evening. A small party of bomb-throwers held off the Bavarian advance on the right flank, taking 20 prisoners.14 Their replacements continued to resist with grenade and bayonet.

Australian and German bodies in a portion of the German 2nd line held throughout the night by the 5th Australian Division. This image is one of a sequence taken by an unknown German officer that were given to Captain C Mills 31st Battalion AIF after the Armistice in 1918. A wounded Captain Mills had been captured by the Germans during the battle. Image: AWM A01562

Australian and German bodies in a portion of the German 2nd line held throughout the night by the 5th Australian Division. This image is one of a sequence taken by an unknown German officer that were given to Captain C Mills 31st Battalion AIF after the Armistice in 1918. A wounded Captain Mills had been captured by the Germans during the battle. Image: AWM A01562

Close-quarter fighting in dark, smoke-filled trenches continued with unimaginable violence. The Germans were unnerved by the furious resistance.15 Bavarian reports mentioned the bravery of the Australian soldiers. It was not enough however to stem the counter-attack. The Bavarians kept coming, driven on by their NCOs.

The situation for the attackers became increasingly desperate. The lower trenches flooded, making them impossible to defend. Wounded drowned in the rising waters. Exhausted, low on ammunition, and in danger of being cut off completely, an unofficial withdrawal began around 4:30 am.16

By 5:30 the situation was assessed to be hopeless. At the cost of several message-runners, the official order to withdraw got through. 5th Division’s survivors made a fighting retreat. Many were cut down in no man’s land, some within meters of safety. Others scrambled back through half-finished communications trenches. A few survivors banded together and fought on in the German lines until they were captured or killed.

Don’t forget me, cobber

A German collecting station on the morning of the 20th July with wounded Australian prisoners of war. Facing the camera, seated central on a box with part of his face bandaged is 5385 Lance Corporal Arnold Blanston Mason. To his right, with the top of his left arm bandaged, is 2134 Private Andreas Voitkun. Image: AWM A01551

A German collecting station on the morning of the 20th July with wounded Australian prisoners of war. Facing the camera, seated central on a box with part of his face bandaged is 5385 Lance Corporal Arnold Blanston Mason. To his right, with the top of his left arm bandaged, is 2134 Private Andreas Voitkun. Image: AWM A01551

850 men of the 53rd went into battle. The Wilson Brothers and William Laing were among the 62517 who did not answer their names at roll call.

In all probability Samuel, Eric and James Wilson set off together in B Company. James was wounded in the neck and sent back to a dressing station.

Samuel and Eric pushed on. An eyewitness account report by Private Eli Taylor explained Samuel’s last moments, possibly during the fighting retreat in the early hours of the 20th.

He was bombing Germans in a trench when about fifty of them rushed out at him. He waited until they got quite near and then threw his remaining bombs down between himself and them. He held the sap alone and was himself killed by a bomb when the others had safely got away.18

Private E B Taylor from B Company verified this story. Taylor added that he believed Samuel Wilson had been recommended for heroism.

Nothing is known of Eric’s fate. Samuel may have fought on to protect his badly wounded brother.19

William Laing’s fate, like many who fell, remains a mystery. ‘Known [only] unto God.’

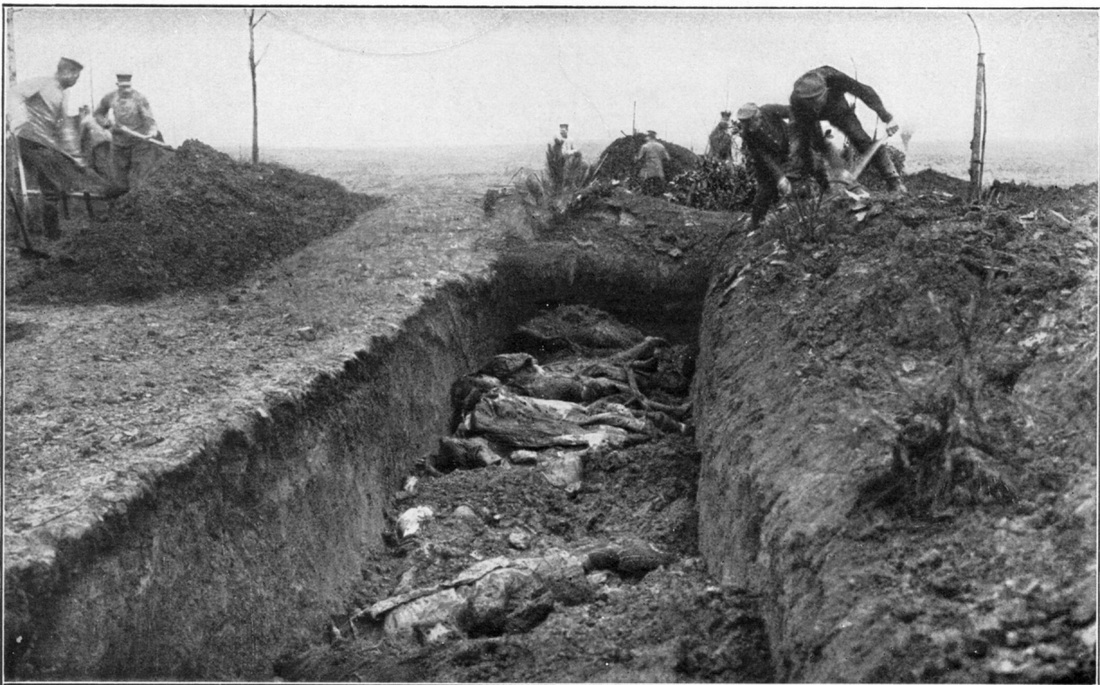

‘Butcher’ Haking, architect of the disaster and Lieut. Gen. Mckay refused a truce after the battle. Australian dead found near, or in the German lines were buried in mass graves. These places were noted in regimental reports but became unidentifiable as the war progressed.

Germans burying British and Australian dead after Fromelles.

Germans burying British and Australian dead after Fromelles.

A cruel state of suspense

Families whose son’s remains were never found were torn with unresolved grief.

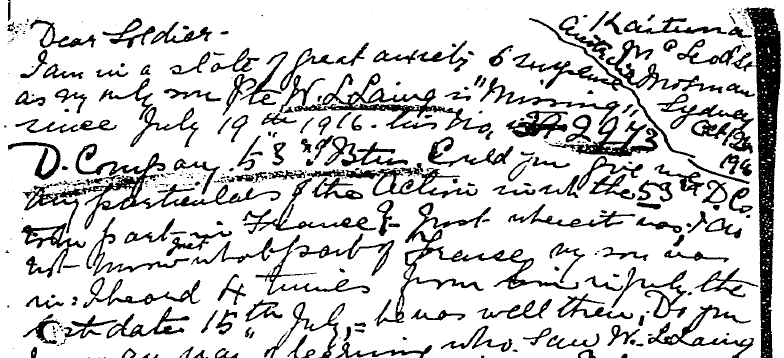

William Laing’s parents sought any news of their son’s whereabouts. Letters to the authorities from his mother reflect her personal torment. On October 9th, 1916, she wrote:

Dear Sir

I am in a cruel state of suspense about my son – No. 2973 Pte. W. L. Laing D Company, 53rd Battalion. Officially reported “Missing” July 19th 1916, would it be possible to find out if he is a “Prisoner of War”? It would be such a relief to us to know if his life has been spared …

When my son wrote last on July 15th he appeared to be well and happy … We had four letters and postcards in July. He was a most kind and considerate son and always wrote so that we would not worry. Would it be possible for us to know which engagement [he] took part in on July 19th? We do not know what part of France D Company 53rd Battalion was in on that date.23

Letter written by Sarah Laing enquiring about her son, William, missing after Fromelles. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/R1493020/

Letter written by Sarah Laing enquiring about her son, William, missing after Fromelles. https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/R1493020/

Like many parents, the Laings exhausted all official avenues of inquiry: International Red Cross, internment camps, hospitals. Second Lieutenant Laing was officially listed as ‘Killed In Action’ fourteen months after he went ‘Missing.’ Sarah Laing wrote:

“People have told me that in spite of messages saying their loved ones are dead, the missing have turned up’‘.

She hoped that, even if her ‘‘boy’s end’ remained unknown, his kit bag could be found: ‘I live in hope there might have been a last letter to us left in it.’24

William’s parents put a memorial notice in the Sydney Morning Herald on 19th of July each year with the words: To live in hearts we leave behind, is not to die.25

Sarah Laing’s grand-niece, Virginia Howard of Mosman recalled:

We were told that though she [Sarah Wilson] lived until 1947, she never got over losing her son and never stopped pressing the army for information about him, long after his name appeared among the dead on the Mosman War Memorial.26

Taking up the search … Virginia Howard with a portrait of her great-uncle William Lewis Laing. Credit:Kate Geraghty Source SMH online 30 January, 2010

Taking up the search … Virginia Howard with a portrait of her great-uncle William Lewis Laing. Credit:Kate Geraghty Source SMH online 30 January, 2010

Photograph of 2/Ltn. Laing who joined as a Privite generously sent by Virginia Howard

Photograph of 2/Ltn. Laing who joined as a Privite generously sent by Virginia Howard

A complex project

Almost immediately, the disaster at Fromelles (or ‘Fleurbaix’ ) became a footnote to the battle of Somme.

After the war, Official Historian Charles Bean visited and photographed the battle site. Bean investigated on behalf of relatives, but neither he nor the War Graves Commission were able to locate the missing soldiers.

The next major official visit to Fromelles was by Adolf Hitler after the defeat of France in 1940. At the time of the battle, he was an unknown Corporal.

In recent times enthusiasts, historians, archaeologists and the media brought have Fromelles back to public attention.

Retired art teacher Lambis Englezos and his fellow enthusiasts believed missing Australian soldiers were buried beside Pheasant Wood, near Fromelles. By 2005 they had gathered enough evidence (based on photographic, archival, Red Cross and Commonwealth war records) that 167 missing soldiers must be buried there.

A Rising Sun badge unearthed at the Commonwealth war grave dig at Pheasant Wood, Fromelles.

A Rising Sun badge unearthed at the Commonwealth war grave dig at Pheasant Wood, Fromelles.

A long, bureaucratic process followed. Media coverage and the threat of an unofficial dig forced the issue. An official exploratory dig by a British led team began in 2008. Findings of the dig and the discovery of archived Bavarian regimental records20 confirming a mass grave put the matter beyond doubt. In 2009, the Australian Government finally got on board. A full excavation led to the discovery, examination, and relocation of soldiers remains. In 2010 Pheasant Wood cemetery was officially dedicated.

A full bibliography and video link detailing the Pheasant Wood story is provided below. As the Department of Veterans affairs site states:

This was a complex project.22

Forensic and DNA testing revealed the identities of the bodies. In March 2010, 128 were announced to be Australian, 3 British, and 44 were unidentified. Initially, 75 Australians were named through DNA testing. A further 21 Australian soldiers were identified including Lieutenant-Colonel Ignatius Bertram Norris.21

As part of DNA testing Lieut. Alan Mitchell (30th Btn.) of “Eulalie” in Shadforth St (pictured top right), and Lieut. Berrol Lazar Mendelsohn (55 Btn.) of 67 Raglan Street (bottom, right), were also identified and buried at Pheasant Wood. The Queenslander, 2/9/1916 reported:

Lieut. Berrol Mendelsohn, whose death in action occurred somewhere in France on July 20, was…second son of the late Mr. S. Mendelsohn, of Queensland, and of Mrs. Mendelsohn, Ullenbar, 67 Raglan Street, Mosman…He was well known in swimming circles, having been a member of the Bondi Club for many years, and won many prizes…He…[was]…sent to Gallipoli, and stationed at Quinn’s Post…He left for the battlefields of France, where his first engagement has proved his last…Mendelsohn’s youngest brother, Oscar, left recently…for the Front.

In 1921, his mother, Abigail Mendelsohn wrote to Army Records:

I am still waiting and hoping that the grave of my darling son has been found, but so far have not had that consolation.

Brothers in arms

Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery

Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery

We can only imagine the reaction of Isabella Wilson, mother of Samuel, Eric, and James when she learned her boys were ‘Missing.’ Compounding her anxiety, the youngest, James had been wounded and could not be contacted. The Wilsons finally heard from James, but he was never to see his mother again. Whilst he was returning to Australia in 1919:

Isabella died of a broken heart, said to be a result of the loss of her sons.27

On March 17th 2010, Esther Gray, daughter of James Wilson, received a call that closed a chapter in her family history. Samuel and Eric had been identified through her DNA:

I got the call from the Australian Army early in the morning, and when they told me I stood there and I could not believe it…it was just so emotional. Their family suffered such grief in not knowing. They passed on the need to know where they were.28

They had been found, together.29

Did they die near each other on the battlefield? Were they identified as brothers and placed side-by-side?

Fittingly, Samuel and Eric Wilson are now buried next to each other at Pheasant Wood Military Cemetery (Plot 2, Row E, Graves 1 and 2.)

If there is a silver lining to the Fromelles story it is this: the Diggers lying in the Pheasant Wood Cemetery lost for generations now have a dignified resting place. At last, surviving relatives (and others) can pay their respects, reflect on the futility of war and find a sense of peace.

Others like William Laing are still remembered at V.C. Corner in the Fromelles Cemetery and at the Australian War Memorial

The Fromelles story continued…

1. Cobbers remembered: Fromelles 19/06/1916

2. Cobbers remembered: Allan Allsop’s ‘terrible night’

3. Cobbers remembered: Lost Diggers of the 53rd

4. Cobbers remembered: Mosman’s dead

5. Cobbers remembered: Fromelles recommended reading

Appendix: Bringing the dead back to life

German reports after the battle gave the Australians high praise:

The enemy fought very bravely, defended himself extremely skillfully and held his ground with exceptional tenacity.30

The Bavarians had also won hard-earned respect from the Australians. Bavarian intelligence reports quoted war-weary POW Diggers after the battle. One Digger said it was:

… almost as if the Germans [could] bring the dead back to life again.31

Professional record-keeping, responsible disposal of the dead, and the preservation of regimental documents by the Bavarians helped Diggers to be found at Pheasant Wood.

So they, and everyone involved with the Fromelles project, have played their part in bringing ‘the dead back to life.’

Bunkerunterstand bei Fromelles, Juli 1916. Image: Bundesarchiv

Bunkerunterstand bei Fromelles, Juli 1916. Image: Bundesarchiv

Bibliography

Books

Bean, C.E.W. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 Volume 3, The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1916 (12th edition, 1941) Chapter 12, Chapter 13.

Barton, Peter and Forsyth, Michael, (translator.) The lost legions of Fromelles: the true story of the most dramatic battle in Australia’s history. Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2014.

Lee, Roger, (Military historian) The battle of Fromelles, 1916. Army History Unit, Canberra A.C.T, 2010.

Lycett, Tim and Playle, Sandra Fromelles: the final chapters: how the buried diggers were identified and their lives reclaimed. Melbourne Viking, 2013.

Lindsay, Patrick Fromelles: our darkest day. Hardie Grant Books, Richmond, Victoria, 2016.

Video

Excellent SBS Dateline doco “Lost and Found”: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/dateline/tvepisode/lost-and-found

Video tributes:

From The lost Diggers of Fromelles: A joint project… http://smcchistory.ning.com/

Eric Wilson: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kQA-diO3yCw&feature=youtu.be

Samuel Charles Wilson: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=onA_-nzFEZg

Alan Mitchell: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xAu6NW-aGi8

Links

Photos of Pheasant Wood Cemetery, Wilson brothers’ graves. Also Lt. Berrol Lazar Mendelsohn of Mosman and Col. Norrris’ headstones, among others. http://thebignote.com/2016/10/18/fromelles-part-seven-fromelles-pheasant-wood-military-cemetery/

Young Genealogist may have found a new photo of the three brothers: https://diaryofayounggenealogist.wordpress.com/2018/03/04/the-wilson-brothers/

Images of soldiers from Pheasant Wood: http://www.inmemories.com/Cemeteries/fromellespheasantwood.htm

Footnotes

11 53rd Battalion (Australia) History: World War 1

12 Lee, Roger & Australia. Dept. of Defence. Army History Unit (2010). The Battle of Fromelles: 1916. Canberra, ACT Army History Unit p144

13 Mcrae, Toni, Remembering brave soldier, Norris

14 Lee, p144

15 Barton, Peter, and Forsyth, Michael, (translator.) The lost legions of Fromelles: the true story of the most dramatic battle in Australia’s history. Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, NSW, 2014. p262

16 Lee, p145

17 AWM 53rd Australian Infantry Battalion https://www.awm.gov.au/collection/U51493

18 AWM; Red Cross Wounded and Missing 3534 Private Samuel Charles Wilson

19 Lycett, Tim & Playle, Sandra, _ Fromelles: the final chapters_. Melbourne, Vic. Penguin 2016 p207

20 Lindsay, Patrick Fromelles: our darkest day. Hardie Grant Books, Richmond, Victoria, 2016. Appendix VI Major-General von Braun Order No. 5220; p229

21 Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery: Identifications

22 Fromelles (Pheasant Wood) Military Cemetery

23 AWM; Red Cross Wounded and Missing: 2973 Private William Lewis Laing

24 Huxley, John, The anguish of not knowing a forebear’s last hours and final resting place

25 Franki, George Their Name Liveth for Evermore: Mosman’s Dead in the Great War 1914-1918

26 Huxley

27 Lycett & Playle, p208

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Barton, p232

31 Ibid. p299