Sugarloaf: no picnic

Men of the 53rd Battalion in a trench in their front line a few minutes before the launching of the attack in the battle of Fromelles.

Men of the 53rd Battalion in a trench in their front line a few minutes before the launching of the attack in the battle of Fromelles.

On the 19th of July 1916, the 5th Australian Division attacked entrenched German positions near the French town of Fromelles.

Stretcher bearer Pte. “Allan” Allsop’s diaries give a vivid if brief account of the battle He notes:

The total casualties numbered 7,800 out of no more than 12,000 troops if there were that many. More than the losses at the landing in Gallipoli, and one of the hardest fought fights in the war to date. Men who were in Gallipoli told me personally that Gallipoli was a picnic to it.1

The Australians actually suffered 5,533 casualties. But this battle was the worst 24 hours in Australian military history.

Wretched, hybrid scheme

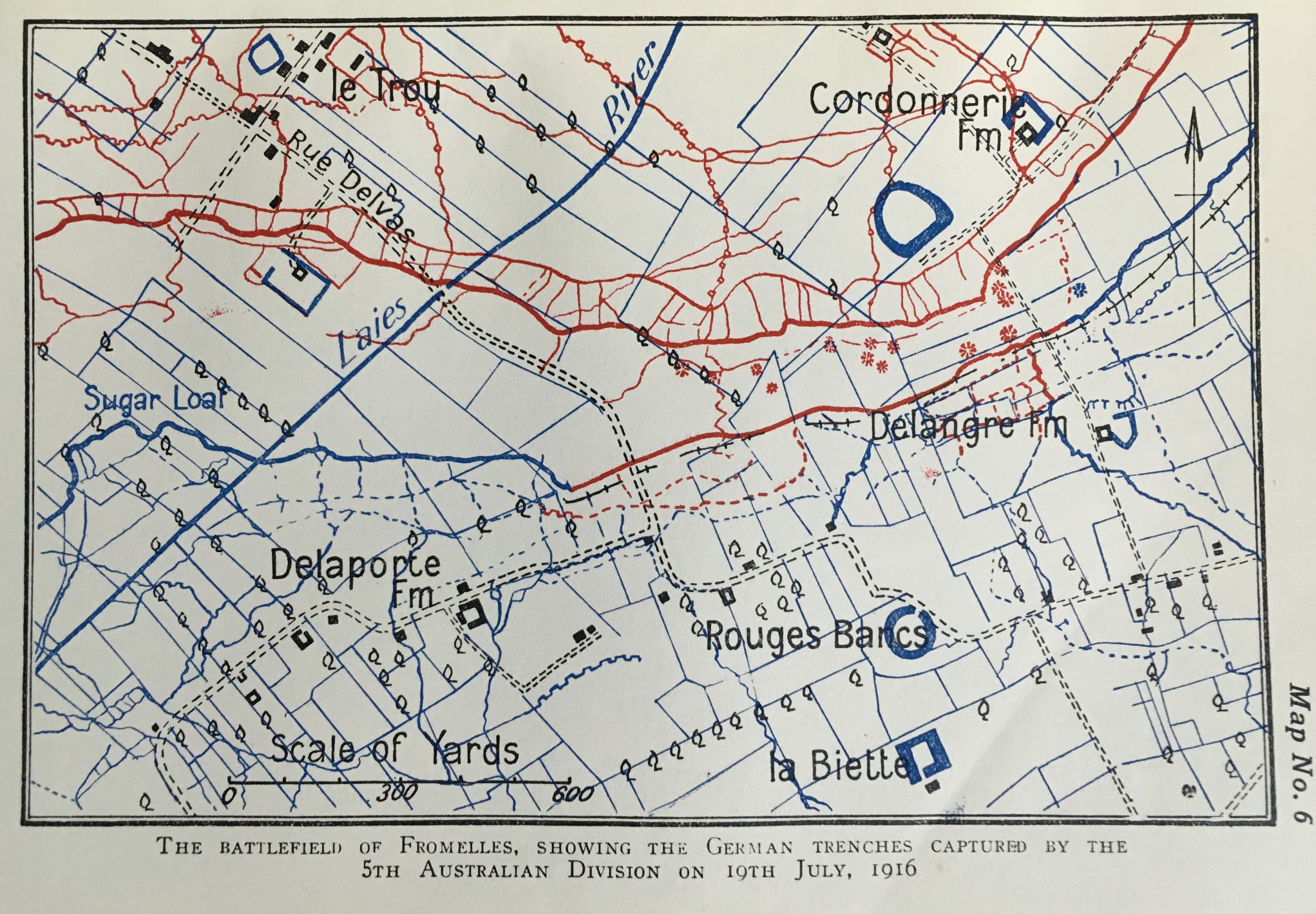

Map from C.E.W. Bean’s Official History showing opposing trenches with ‘Sugarloaf’ on the left.

Map from C.E.W. Bean’s Official History showing opposing trenches with ‘Sugarloaf’ on the left.

Fromelles was a doomed plan from its conception. Australian Brigadier-General ‘Pompey’ Elliot labelled it ‘a wretched, hybrid scheme.’2

Sir Richard Haking had known Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig from their Staff College days. Haig admired ‘Dicky’ Haking’s theories of attacking the enemy with élan] His indifference to casualties and bullying behaviour did not endear him to the man in the trench, or his staff. Hence his nickname, the ‘Butcher’.

Haking was obsessed with the Sugarloaf. He was the architect and driving force behind two previous attempts. Sir Douglas Haig amended and signed off on his latest plan, with the proviso: enough artillery support must be provided.

France. 11 November 1918. View of the concrete blockhouses in the German third line on the Fromelles-Aubers Ridge. It was towards these positions that the 14th Australian Infantry Brigade attacked in the battle of Fromelles on 19 July 191

France. 11 November 1918. View of the concrete blockhouses in the German third line on the Fromelles-Aubers Ridge. It was towards these positions that the 14th Australian Infantry Brigade attacked in the battle of Fromelles on 19 July 191

The troops had to cross through barbed-wired in a waterlogged no-mans land. They faced the experienced Bavarian 6th Division. They had prepared breastworks and trenches that fed off the fortified ‘Sugarloaf’. Their lines included concrete dugouts, fortified blockhouses, and machine-gun pillboxes. The Germans also had the high ground. Their observation posts could see the movement of troops over the battlefield including the build-up behind British lines.

The newly formed Australian 8th, 14th and 15th Brigades were walking into the same trap that had befallen previous attacks. The Germans just had to survive the preparatory bombardment.

Pompey Elliot confided to Maj. Howard (on Haig’s staff) his fears of a catastrophe. Howard agreed it would be ‘a bloody holocaust.’

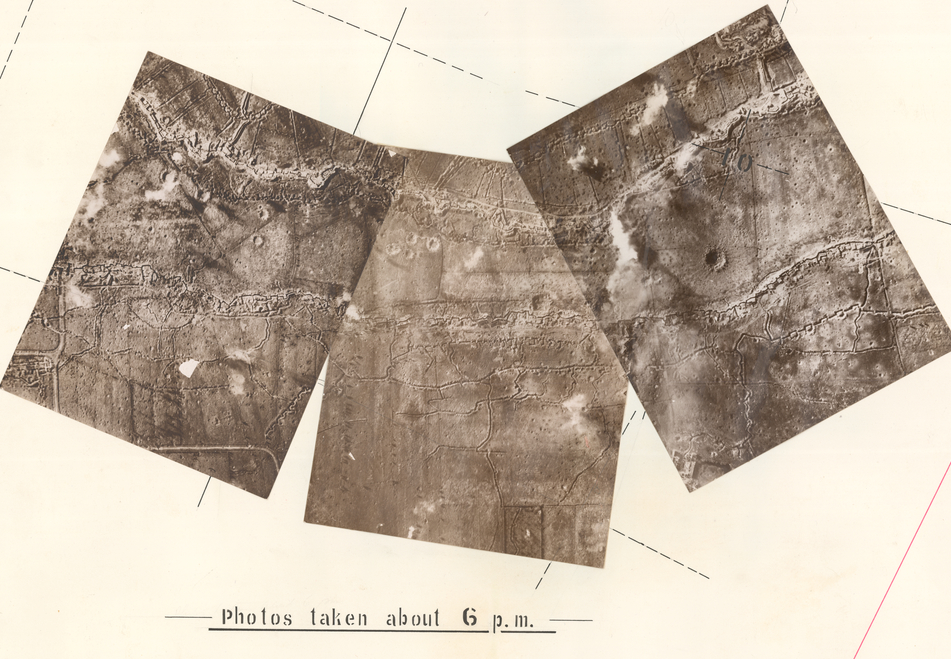

Aerial photographs taken at about 6pm on 19 July 1916. The British breastworks run across the top of the mosaic, from left to right, with no man’s land cratered by mines. The German defences cross the middle of the photo. Two landmarks are just visible in the right-most photo: Cordonnerie Farm at top right, and Delangre Farm bottom left. In this section of the British line (left to right) were the 54th, 31st and 32nd Battalions AIF. Image: AWM AWM2016.38.80

Aerial photographs taken at about 6pm on 19 July 1916. The British breastworks run across the top of the mosaic, from left to right, with no man’s land cratered by mines. The German defences cross the middle of the photo. Two landmarks are just visible in the right-most photo: Cordonnerie Farm at top right, and Delangre Farm bottom left. In this section of the British line (left to right) were the 54th, 31st and 32nd Battalions AIF. Image: AWM AWM2016.38.80

There were few eyewitnesses who survived to recall their stories (and even less who talked about their experiences.) But those who did, give us an idea of what the holocaust in no man’s land was like.

Private Jimmy Downing, 57th Battalion wrote:

Scores of stammering German machine-guns spluttered violently, drowning the noise of the cannonade. The air was thick with bullets, swishing in a flat, criss-crossed lattice of death. There were gaps in the lines of men – wide ones, small ones. The survivors spread across the front, keeping the lines straight … The bullets skimmed low, from knee to groin, riddling the tumbling bodies before they touched the ground. Hundreds were mown down in the flicker of an eyelid, like great rows of teeth knocked from a comb, but still the line went on, thinning and stretching. Wounded wriggled into shellholes or were hit again. Men were cut in two by streams of bullets [that] swept like whirling knives. And still the line went on … It was the Charge of the Light Brigade once more, but more terrible, more hopeless – magnificent, but not war – a valley of death filled by somebody’s blunder.

Waldo Zander of 30th Battalion, supporting the initial attack wrote a less Romantic version of what it was like in no-mans land:

The Hun sent some incendiary shells over, and these set alight…anything they came in contact with when they burst, their flickering flames throwing a ghostly light over the dead and debris lying about. One poor wretch who had his arm blown off by a shell, was crawling painfully across No Man’s Land endeavouring to reach to reach shelter and aid, when one of these diabolical incendiary shells burst nearby, splintering him with its burning contents. By the light made by a bursting shell, he was seen to be frantically trying to smother the flames that were eating into his very flesh, tearing up handfuls of mud and earth in his endeavour and agony. His screams could be heard for, a second or two- then [there was] silence. We passed his body the next morning one side of it was cruelly charred and burned.4

Sadly, Pompey’s Battalion was ordered into the attack after it should have been called off.

Elliott had protested about the hopelessness of the task; he was in the front line at zero hour and visited his troops before they were withdrawn. Next morning, Arthur Bazley, Bean’s assistant, saw him greeting the remnants: ‘no one who was present will ever forget the picture of him, the tears streaming down his face, as he shook hands with the returning survivors’.5

Of Elliot’s 887 men only one officer and 106 Diggers made roll call the next day.6

What an insult!

The body of an Australian soldier killed in the German 2nd line, photographed by Hauptmann Eckart, intelligence officer of the 6th Bavarian Division. Image: AWM A01566

The body of an Australian soldier killed in the German 2nd line, photographed by Hauptmann Eckart, intelligence officer of the 6th Bavarian Division. Image: AWM A01566

British newspapers described the battle as ‘a raid.’ Allsop wasn’t impressed:

Whatever results were attained ours was the first Australian battle in France. Disgust and feelings of angry disappointment reigned for days afterwards when a report something like this appeared in the “Daily Mail”. “A raid was carried out south of Armentieres in which Australians took part. We captured 140 prisoners.” What an insult!7

General Haking in his official report stated that the German wire and defences had been destroyed prior to the advance, and, the infantry had a “clear run” to the enemy trenches:

With two trained divisions the position would have been a gift after the artillery bombardment.

Haking blamed the ‘newness’ Australian regiments for the attacks failing. He accused the British 61st Division for ‘not [being] sufficiently imbued with the offensive spirit.’8

To add insult to injury, he concluded:

I think the attack, although it failed, has done both Divisions a great deal of good [author’s emphasis].

Reginald Hugh Knyvett, with the 15th Battalion witnessed how much good had been done by the attack, and the subsequent decision to leave the dead and wounded out on the battlefield..

The sight of our trenches that next morning is burned into my brain. Here and there a man could stand upright, but in most places, if you did not wish to be exposed to a sniper’s bullet you had to progress on your hands and knees. In places, the parapet was repaired with bodies—bodies that but yesterday had housed the personality of a friend by whom we had warmed ourselves. If you had gathered the stock of a thousand butcher-shops, cut it into small pieces and strewn it about, it would give you a faint conception of the shambles those trenches were …

Australian and German bodies in a portion of the German 2nd line held throughout the night by the 5th Australian Division. This image is one of a sequence taken by an unknown German officer that were given to Captain C Mills 31st Battalion AIF after the Armistice in 1918. A wounded Captain Mills had been captured by the Germans during the battle. Image: AWM A01562

Australian and German bodies in a portion of the German 2nd line held throughout the night by the 5th Australian Division. This image is one of a sequence taken by an unknown German officer that were given to Captain C Mills 31st Battalion AIF after the Armistice in 1918. A wounded Captain Mills had been captured by the Germans during the battle. Image: AWM A01562

Out in no man’s land –

There were men who were forty-eight hours without food or drink, without having their wounds dressed, knowing that the best they had to hope for was a bullet … again and again, would they refuse to be taken until we should look to see if there was not someone alive in a neighbouring shell-hole. They would tell us to “look in the drain, or among those bushes over there” … there were men there with legs off, and arms hanging by a skin, and men sightless, with half their face gone, with bowels exposed, and every kind of unmentionable wounds…

Dead soldiers on the left flank of the Australian position in the German 2nd line, photographed by a German soldier. Image: AWM A01555

Dead soldiers on the left flank of the Australian position in the German 2nd line, photographed by a German soldier. Image: AWM A01555

Simply put, the Fromelles ‘diversion’ was an utter failure. German reserves were not diverted from the Somme offensive. German High Command was not tricked into thinking the main British attack would fall on the Aubers ridge. In fact, Haking’s battle plans found on a dead officer shortly after the attack started, confirmed this.9

The 5th Australian Division’s losses rendered it incapable of action for many months. The British and Canadians also suffered heavy casualties.

The Germans lost over 1,600 men. Corporal Adolf Hitler, a message runner with the 16th Bavarian Reserve was, unfortunately, not among them.

The Fromelles story continued…

1. Cobbers remembered: Fromelles 19/06/1916

2. Cobbers remembered: Allan Allsop’s ‘terrible night’

3. Cobbers remembered: Lost Diggers of the 53rd

4. Cobbers remembered: Mosman’s dead

5. Cobbers remembered: Fromelles recommended reading

Footnotes

1 W. J. A. Allsop diary, 2 July -13 September 1916. p 22, SLNSW – see also a browser for Allsop’s diaries

2 Lindsay, Patrick Fromelles : our darkest day. Richmond, VIC; Hardie Grant, 2016. p73

3 Ibid. p70

4 Sebag-Montefiore, Hugh Somme : into the breach. London Viking, an imprint of Penguin Books, 2016. p.263

5 Hill, A. J. Elliott, Harold Edward (Pompey) (1878–1931) Australian Dictionary of Biography Online: http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/elliott-harold-edward-pompey-6104

6 Barton, Peter The lost legions of Fromelles: the true story of the most dramatic battle in Australia’s history. Crows Nest, NSW; Allen & Unwin, 2014. p.216

7 W. J. A. Allsop diary, 2 July -13 September 1916, SLNSW retreived online at: http://archival-classic.sl.nsw.gov.au/item/itemDetailPaged.aspx?itemID=873611

8 Lindsay, p.157

9 Barton, p.251

Appendix: Bearing witness

Reginald Hugh Knyvett’s description of the aftermath of Fromelles from Chapter XIX: The Battle of Fleurbaix

When darkness came the second night, we had organized parties of rescue, but we still had practically no stretchers, and the most of the men had to be carried in on our backs.

I went out to the bridge, and in between machine-gun bursts began to pull down that heap of dead. Not all were dead, for in some of the bodies that formed that pyramid life was breathing. Some were conscious but too weak to struggle from out that weight of flesh. Machine-guns were still playing on this spot, and after we had lost half of our rescuing party, we were forbidden to go here again, as live men were too scarce.

But the work of rescue did not cease. Two hundred men were carried in from a space less in area than an acre. One lad, who looked about fifteen, called to me: “Don’t leave me, sir.” I said, “I will come back for you, sonny,” as I had a man on my back at the time. In that waste of dead, one wounded man was like a gem in sawdust—just as hard to find. Four trips I made before I found him, then it was as if I had found my own young brother. Both his legs were broken, and he was only a schoolboy, one of those overgrown lads who had added a couple of years in declaring his age to get into the army. But the circumstances brought out his youth, and he clung to me as though I were his father. Nothing I have ever done has given me the joy that the rescuing of that lad did, and I do not even know his name. He was the only one who did not say: “Take the other fellow first.”

There were men who were forty-eight hours without food or drink, without having their wounds dressed, knowing that the best they had to hope for was a bullet. That the chances were they would die of starvation or exposure, and yet, again and again, would they refuse to be taken until we should look to see if there was not someone alive in a neighbouring shell-hole. They would tell us to “look in the drain, or among those bushes over there.” During the day they had heard a groan. A groan, mind you, and there were men there with legs off, and arms hanging by a skin, and men sightless, with half their face gone, with bowels exposed, and every kind of unmentionable wounds, yet someone had groaned. Why some had gritted teeth on bayonets, others had stuffed their tunics in their mouths, lest they should groan. Someone had written of the Australian soldier in the early part of the war, “that they never groan,” and these men who had read that would rather die than not live up to the reputation that some newspaper correspondent had given them.

I lay for half an hour with my arms around the neck of a boy within a few yards of a German “listening post”, while the man who was with me went back to try and find a stretcher. He told me he had neither mother nor friend, was brought up in an orphanage, and that no one cared whether he lived or died. But our hearts rubbed as we lay there, and we vowed lifelong friendship. It does not take long to make a friend under those circumstances, but he died in my arms and I do not know his name.

There was another man who was anxious about his money-belt; perhaps it contained something more valuable than money. I went back for it, stuffing it in my pocket, and then forgot all about it. When I thought of it again the belt was gone, and the owner had gone off to hospital. I do not know who he was, and maybe he thinks I have his belt still.

One of the most self-forgetful actions ever performed was by Sergeant Ross. We found a man on the German barbed wire, who was so badly wounded that when we tried to pick him up, one by the shoulders and the other by the feet, it almost seemed that we would pull him apart. The blood was gushing from his mouth, where he had bitten through lips and tongue, so that he might not jeopardize, by groaning, the chances of some other man who was less badly wounded than he. He begged us to put him out of his misery, but we were determined we would get him his chance, though we did not expect him to live. But the sergeant threw himself down on the ground and made of his body a human sledge. Some others joined us, and we put the wounded man on his back and dragged them thus across two hundred yards of No Man’s Land, through the broken barbed wire and shell-torn ground, where every few inches there was a piece of jagged shell, and in and out of the shell-holes. So anxious were we to get to safety that we did not notice the condition of the man underneath until we got into our trenches; then it was hard to see which was the worst wounded of the two. The sergeant had his hands, face, and body torn to ribbons, and we had never guessed it, for never once did he ask us to “go slow” or “wait a bit.” Such is the stuff that men are made of.

It sounds incredible, but we got a wounded man, still alive, eight days after the attack. It was reported to me that someone was heard calling from No Man’s Land for a stretcher-bearer, but I suspected a German trap, for I did not think it possible that any man could be out there alive when it was more than a week after the battle and there had

been no men missing since. However, we had to make sure, and I took a man out with me named Private Mahoney; also a ball of string. We still heard the call, and as it came from nearer the German trenches than ours we knew they must hear as well. When we got near the shell-hole from which the sound came I told Mahoney to wait, while I crawled round to approach it from the German side. I took the end of the ball of string in my hand, so as to be able to signal back, and from a shell-hole just a few yards away I asked the man who he was and to tell me the names of some of his officers. As he seemed to know the names of all the officers I crawled into the hole alongside him, though I was still suspicious, and signaled back to my companion to go and get a stretcher.

As soon as I had a good look at the poor fellow I knew he was one of ours. His hands and face were as black as a Negros, and all of him from the waist down was beneath the mud. He had not strength to move his hands, but his voice was a good deal too strong, for he started to talk to me in a shout: “It’s so good, matey, to see a real live man again. I’ve been talking to dead men for days. There was two men came up to speak to me who carried their heads under their arms!”

I whispered to him to shut up, but he would only be quiet for second or two, and soon the Germans knew that we were trying to rescue him, for the machine-gun bullets chipped the edge of the hole and showered us with dirt. In about half an hour Mahoney returned with the stretcher, but we had to dig the poor fellow’s limbs out, and only just

managed to get into the next hole during a pause in the machine-gun bursts. To cap all, our passenger broke into song, and we just dropped in time as the bullets pinged over us. These did not worry our friend on the stretcher, nor did the bump hurt him, for he cheerfully shouted: “Down go my horses!” We gagged him after that and got him safely in, but the poor fellow only lived a couple of days, for blood-poisoning had got too strong a hold of his frail body for medical skill to avail. His name I have forgotten, and the hospital records would only state: “Private So-and-so received [a certain date]; died [such a date]. Cause of death—tetanus.”