Finding the fragments that complete a picture is one of the rewards of digging in the archives. The diaries of two Mosman men have revealed for John and Vicki Andrews the deep regard felt for a forebear by the men of his command.

Allan Allsop, of Brierley Street, Mosman, and Langford Wellman Colley-Priest, of Sutherland Street, Cremorne, were stretcher bearers in the 8th Field Ambulance. Major Maldwyn Leslie Williams was one of their senior officers.

Allsop kept a diary, as did Colley-Priest, who also wrote a brief account of the ambulance on active service.

Thanks to the State Library of NSW, who collected and transcribed these diaries, and Mosman’s Anzac centenary project, John and Vicki have gained another perspective on Major Leslie Williams’ life and service.

Maldwyn Leslie Williams

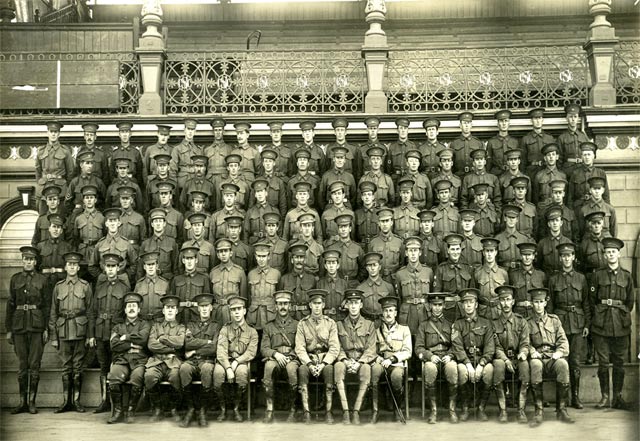

“C” Section, 8th Field Ambulance, before leaving Australia. Major Leslie Williams is seated in the front row (sixth from left).

Maldwyn Leslie Williams — known as Leslie — was a doctor and surgeon from Bendigo, Victoria. He was married to Margaret Grant, a nurse he had met at Bendigo Base Hospital.

When he embarked with the A.I.F. on 10 November 1915, he left a daughter, 5 years of age, and another child on the way. Mary Helen, later called Leslie, was born a few weeks after his departure.

Major Williams first distinguishes himself to the Mosman diarists when the 14th and 15th Brigades, of which the 8th Field Ambulance was a part, were ordered to march 35 miles through the desert from Cairo’s outskirts to defend the Suez Canal. Planning was poor and the troops suffered severely from the heat and lack of water.

Major Williams did excellent work, and very often I saw him helping chaps along or carrying their packs.

— Langford Colley-Priest

Dodging about amongst the fallen as fast as his horse could carry him was our Major Williams, a Bendigo man, and one whom the infantrymen praise as a “white man”. He worked beautifully. This officer stands out from all others though they all let their horses to convey somebody in.

— Allan Allsop

In camp, 1915. Williams is second from left.

On reaching the Western Front in 1916, the 8th Field Ambulance had their baptism of fire in July at the battle now known as Fromelles.

On arriving at the firing line grim sights confronted us. Dead & wounded lay in heaps behind the parapet and worn-out Australians crouched close under cover. The looks in their faces and on the faces of those lying on the ground greatly impressed me. Chaos and weird noises like thousands of iron foundries, deafening and dreadful, coupled with the roar of high explosives on coal-boxes as they ripped the earth out of the parapet, prevailed as we crept along seeking first of all the serious cases of wounded. Backwards & forwards we travelled between the firing line and the R.A.P. with knuckles torn and bleeding due to the narrow passage ways. “Cold sweat”, not perspiration, dripped from our faces and our breath came only in gasps.

— Allan Allsop

Amidst the horror described by the diarists is the selfless service of Williams.

Having got to this stage I was almost forgetting one of the most outstanding and brilliant episodes of the fight. While working in the firing line when the fray was at its height we passed Major Williams of our Ambulance carrying a stretcher with a Private from the infantry. With no headgear on and perspiration running off him I was simply astounded, so much so that I paused to watch him. Yes, a Major silently working in the very front line and doing a private’s work. Until I saw him I understood that he would be back at the Brewery to perform operations and rearrange dressings as required.

Here we have the White Man so well remembered and respected by everyone since the memorable great march in Egypt.

— Allan Allsop

Today the term is not one we would use, because we know and live with the tragic consequences of racism and paternalism. But it was common at the time. Its meaning is bound up in ideas of Empire, and expectations of integrity, honour and self-sacrifice. Amidst a hundred or thousand more incidents, Williams’ behaviour was remarkable enough to be recorded by at least two men of his unit.

(Major Williams’ own account of Fromelles can be read in Tony Millar’s biography that can be downloaded from the Australian War Memorial.)

‘Somewhere in France’ – 8th Australian Field Ambulance, 1st September 1917. A postcard sent home from the front by Allan Allsop.

The 8th Field Ambulance next saw action on the Somme as the dreadful winter of 1916 closed in on that desperate battle of attrition.

… we are now carrying under heavy fire when other men in the dugout cannot venture out. The flare lights at night show us up, hence the liability of being picked out by machine guns. Climbing over trenches and round the shell holes where sometimes the path is only 6 inches wide and slippery the result was simply awful. Stretcher and bearers fell time after time but still we had to plod on. It’s the heaviest and most exhausting duty on the field as even infantry admit. When our attack comes in a day or two I don’t know how we are to get on.

— Allan Allsop

Private Robert Troup, Major Williams’ batman. This photo was sent home to the Williams family.

As they came out of the line, on 7 November, Major Williams was promoted Lieutenant-Colonel and given charge of the 1st Field Ambulance.

Their next meeting was not happy. Allsop writes:

Friday 2 March 1917

Lt. Col. Williams who used to be a Major in our unit came down from the front line shot through the lungs. He is in a serious condition.Sunday 4 March

News to hand that Lt. Col. Williams died last night at 9 p.m. Party to go from this unit tomorrow to be present at his funeral.Monday 5 March

Marched off to Edgehill – between Dernancourt and Buire – and witnessed the burial of Lt. Col. Williams. A party of about 26 from our unit attended. Bob Troup the batman who left Aust. with Lt. Col. Williams fainted at the graveside & Capt. Irvine & Major Donald were deeply affected.

Colley-Priest also records the loss in his diary.

About March the 12th [1917] the Unit received the sad news of the death of Colonel Williams. He was killed whilst inspecting the Aid Posts. He has been with our Unit right from the very start (at Queens Park) & only left us last December… He was most popular amongst the men here, a thorough sport, & a white man all through. In cricket, football, or any other sports he was always to the fore & joined in all our games, I was really very sorry when I heard the sad news.

The day before he died Williams made a codicil to his will, leaving his batman Robert Troup 15 guineas, about 10 weeks wages.

Troup, who collapsed at the burial, had been with Williams from the start. He had met his daughter before they embarked, and wrote often to his family. That connection has survived the century, with Vicki Andrews in contact with his daughter-in-law and grandson. Troup returned to Waverley after the war, picked up his job as a tram driver, and lived to a ripe old age.

The connection with Dernancourt in France is also sustained, with Williams’ story shared between their school and Castlemaine High, and plans for the Mayor of Dernancourt to lay a wreath on Williams’ grave in remembrance.

Sources & links

- Tony Millar’s biography of Leslie Williams

- W.J.A. Allsop diary

- Allsop’s diary, mapped

- Allan Allsop photographs on Flickr

- Colley-Priest diary, 9 November 1915-11 June 1919 – transcript

- The 8th Australian Field Ambulance on active service : a brief account of its history and services from 4th August 1915 to the 5th March 1919

Thanks John and Vicki Andrews for the story and the photos.