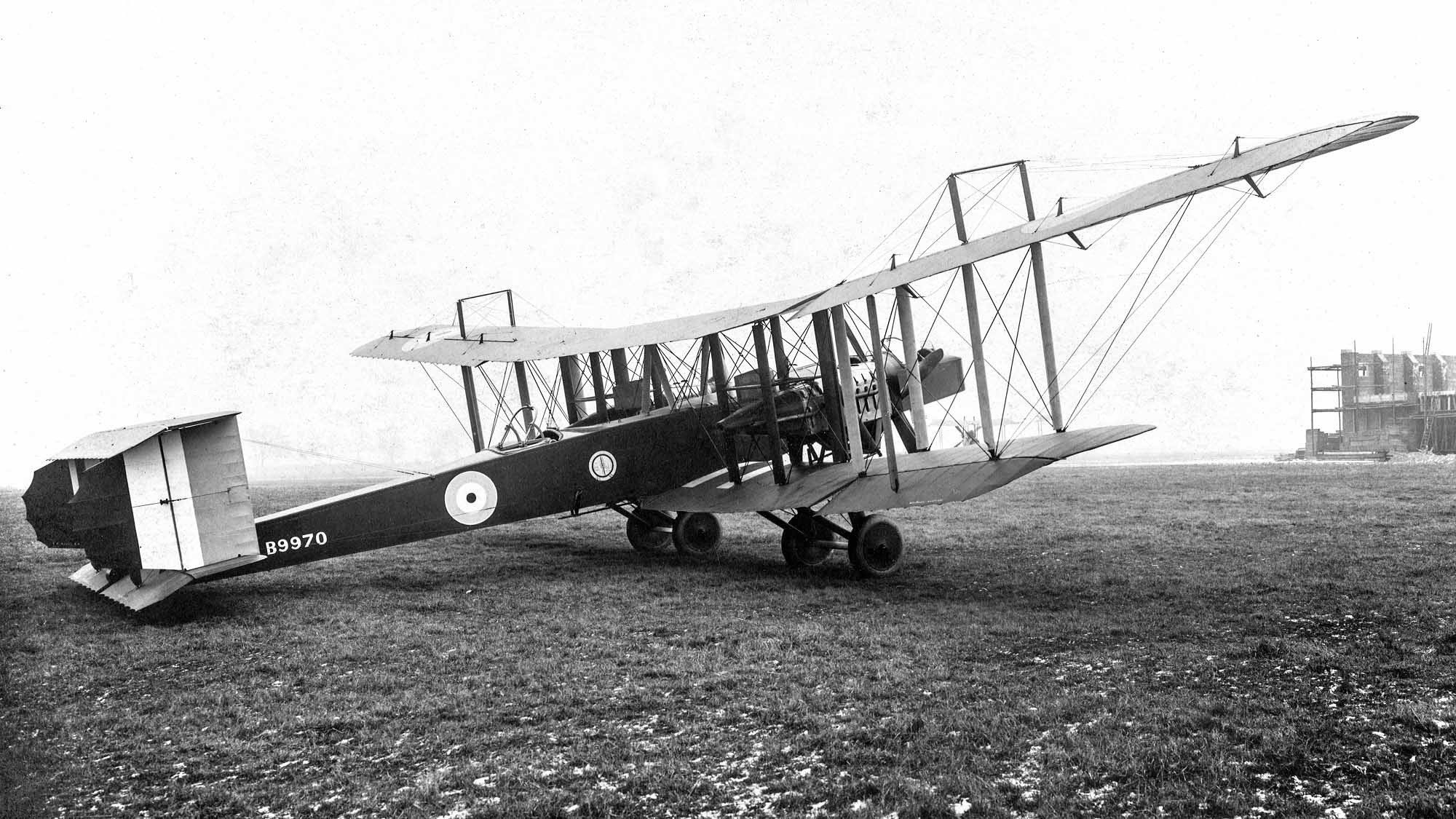

The Blackburn Kangaroo, named because of the location of the observer in the forward ‘pouch’. It’s wingspan was 15 ft less than the Handley Page 0/1-400 bomber but could could carry over 2000lb bombs with 3 crew. On coastal patrol Kangaroos sunk at least 3 German U-boats during the war. Source: ‘The Greatest Air Race’ by Nelson Eustis.

The Blackburn Kangaroo, named because of the location of the observer in the forward ‘pouch’. It’s wingspan was 15 ft less than the Handley Page 0/1-400 bomber but could could carry over 2000lb bombs with 3 crew. On coastal patrol Kangaroos sunk at least 3 German U-boats during the war. Source: ‘The Greatest Air Race’ by Nelson Eustis.

‘Two other Smiths, Ross and Keith, flew their Vickers Vimy out to Australia in 28 days, winning the prize of £10,000 and knighthoods for this magnificent feat.’

-Charles Kingsford Smith on the England to Australia air race he couldn’t enter.

And then suddenly it was all over

Smithy had survived close calls with death, including being blown up, shot down, and a dose of the deadly ‘Spanish flu’. He recalled:

There was I with the remains of a war wound, a war gratuity and a war decoration, with the wide world before me…We were young and full of beans and ready for anything…In fact the new days of Peace seemed strangely dull and flat after the old days of war.1

But he found ways to break the boredom. On one occasion he was caught by a landowner shooting pheasants from the air, to furnish the Officer’s weekly dinner:

Thereby breaking some ancient feudal lore. The penalty for this, according to the farmer, was deportation or transportation to Australia2

The charge of poaching a hare was eventually dropped. Smithy’s response: write a dirty ditty about the farmer. He sang it to banjo accompaniment in the mess, to everyone’s amusement. But this was not the first, nor last time, Smithy would fall foul of the Establishment. More on that later.

‘We were young and full of beans and ready for anything’ Smithy and fellow pilot entrepreneurs – Cyril Maddocks and Val Rendle in 1919. Source ‘Flying Matilda’ by Norman Ellison

‘We were young and full of beans and ready for anything’ Smithy and fellow pilot entrepreneurs – Cyril Maddocks and Val Rendle in 1919. Source ‘Flying Matilda’ by Norman Ellison

Smithy recalled how pioneering aviation at the time had set the public’s imagination alight:

1919 had come in with a rush…new marvels were being accomplished. Alcock and Brown had flown across the Atlantic; Harry Hawker had become a national hero, and to us a tempting prize was held out by the Commonwealth Government which offered £10,000 to the first Australian who could fly from England to Australia.

…it was such an adventure that appealed to people like us, and others like us, too. There were dozens of Australian airmen in England at the time, and they all began feverishly to lay their plans for the flight.

Our idea was to fly in a Blackburn Kangaroo twin-engine machine, and it seemed a very good idea at the time…3

It seemed like a very good idea at the time…

Smithy, years later, explains what happened to his very good idea in an off-handed way:

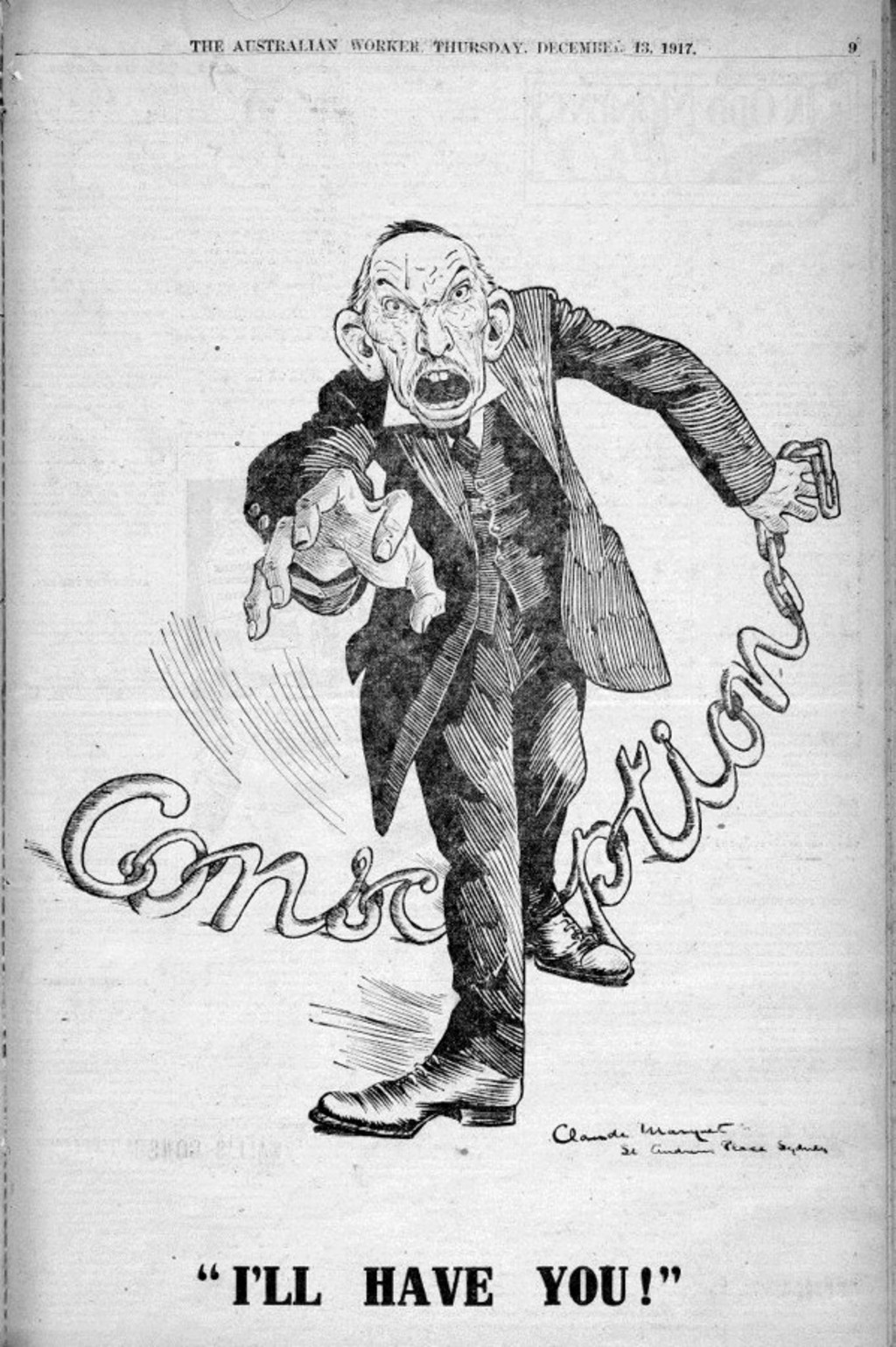

Smithy blamed Billy Hughes as ‘a n_ in the woodpile’. Hughes’ referendums on Conscription split the nation

W.M. Hughes, our war-time Prime Minister, who was all-powerful those days…put his foot down. We were too young; we were too inexperienced; particularly, we had no navigation knowledge or experience for such a tremendous journey. He absolutely forbade it and that was the end of the plan.

We sold the machine after an official veto had been placed on our venture by the Air Ministry. There was nothing else to be done…4

In the late 1950’s Norman Ellison explained in detail Smithy’s reasons for disqualification. Whilst interesting and recommended reading, it is to a later Journalist, Ian Mackersay, we turn. He noted:

- The ‘Kangaroo’ belonged to Blackburn. They couldn’t sell it even if they wanted to.

- The British air ministry did not forbid the flight. An Australian government race was really none of its business.

- It was unlikely that Prime Minister Hughes would have intervened. He was an enthusiastic supporter of the event and in London he attended at least one planning meeting with Cyril Maddocks.

- Race conditions and safety lay with the Royal Aero Club: The club had never taken to vet all entrants and refuse the unsuitable, and there is no evidence it rejected the applications of Kingsford Smith, Maddocks and Rendle.

Mackersay also argues Smithy’s navigation skills weren’t the issue:

Smithy had proved himself a pilot of above average competence and experience on nearly two dozen aircraft types at a time when long-distance navigation didn’t exist as an aviation science. Most of those entering the race had been wartime fighter pilots whose operational flights had rarely exceeded 50 miles. Had a lack of navigation skills been a genuine concern, it would have disqualified most of the other entrants. In any case the navigation issue had been taken care of by the Royal Aero Club. In the middle of June, it had declared that all competing aircraft would be required to carry ‘ a competent navigator’ who would be one of the pilots. At the same time the Australian government had arranged for the RAF to provide navigation training for any pilot who wanted it. Had this been the only impediment Smithy would have taken a short course.5

So we need to look for other reasons why he couldn’t compete.

We would dash back and buy others to replace the crashed machines.

In 1919 Smithy ‘clubbed together’ to co-found a charter company and purchased two DH6 aircraft. In his words:

…very cheaply from Air Ministry war stocks, which were surplus…we flew them on sundry commercial jobs, joy riding, taxi flights and so on.

The first joy-riding venture in England. Smithy is on the left. The aircraft appears to be a DH6.

The first joy-riding venture in England. Smithy is on the left. The aircraft appears to be a DH6.

Smithy worked with Blackburn Co, on the Kangaroo at the same time. He wrote home on 13 June:

I’m quite confident she’ll pull through…The Shell company are cabling to all their representative in the Dutch East Indies to assist us in every way and Rolls-Royce are fitting special 270hp engines…We had to borrow a hundred quid for the entrance fee for the race as well as spend lots rushing around.6

Several months later his letters were less confident and indicate a split with Blackburn:

I’ve written to two or three other concerns asking for particulars of equally capable machines and the cost of equipping one for the flight. I’ve also written to Harold to see if he knows anyone in America who would finance the journey. It would be better on our own, independent of the Blackburns altogether.’7

In desperation, Smithy asked his brother Harold for a £2000 loan (several years earnings). Harold declined.

So why had his relationship with Blackburn broken down? The press were touting Smithy as the up-and -coming lead pilot for the Kangaroo. He’d even had letters of support from General’s Monash and Birdwood.

King Dick

No. 19 Squadron RFC with Smithy second row, second from the right- the one with no cap.

Smithy had a reputation as a ladies man, and this started when he was a flying instructor in England. His fellows nick-named him ‘King Dick’. John Stannage, Smithy’s long term friend and wireless operator on later flights, recalled the story of their first crash in the UK:

Smithy and Maddocks were flying home after a hard day’s work giving rides at the village fair…An argument arose whether they would fly straight home or land at the estate of a gentleman whose daughter Smithy was, at that moment, quite ardently in love. Smithy hauled one way on the controls, Maddocks the other. Presently something snapped. It was a control wire.’8

In the forced landing the aircraft crashed into a ditch and was wrecked. Mackersay writes:

A few weeks later, trying to land in fog, Smithy crashed a second aircraft, wrapping it round an oak tree…Both aeroplanes were replaced in a deal with Aircraft Disposals Board which, according to Stannage, was ‘shrouded in mystery’. The planes were being replaced by the insurers, who became alarmed when a third aircraft went up in smoke following an engine fire in mid-air. The fourth aircraft to go was one of the replacements.

Smithy had developed a practice of offering flights to casual female acquaintances on the pretext of giving them flying lessons. The trips would often end in secluded trysting spots. On the last occasion, said Stannage, ‘he was taking a very lovely little nurse for a short instruction flight.’ Preparing to land, the frightened pupil gripped the controls so hard that Smithy couldn’t move them. The aircraft hit the ground, badly damaging the undercarriage and wing. ‘There was by this time insufficient money to pay for repairs,’ said Stannage, ‘And most certainly they could not ask for more machines.’9

Crashed Be2. These and other WW1 training aircraft such as DH6 and Avro aircraft were purchased. Source: AWM H12729/13

Crashed Be2. These and other WW1 training aircraft such as DH6 and Avro aircraft were purchased. Source: AWM H12729/13

More than the value of our buses

As Mackersay surmises:

They were not only crashing their aeroplanes at a frequency reflecting little credit on someone with Smithy’s above-average piloting skills, but they had also, with the unwitting help of the insurers, who were covering their machines extremely well, become profitable aircraft-traders.

From his letter home is seems Smithy saw the whole thing as quite enterprising:

Maddocks and I made about £40 in two afternoons with that one remaining machine…we sold it to three chaps, who thought it looked easy to make money that way, for twice as much as we paid for it….We had enough cash to buy three new and better type machines…I bet before we start our flight to Australia we’ll make more than the value of our buses.

But as Mackersay points out, others took a dim view of this behaviour:

…the extraordinary toll of accidents and rumours about questionable insurance claims and the hedonistic activities of the directors of Kingsford Smith-Maddocks Aeros Ltd came to the attention of the highly principled Robert Blackburn), who was not amused. He called for a report into the company. What he learned was quickly to bring bad news for Smithy.10

The Air Marshal’s recollection

Lieutenant General Sir Harry Chauvel (front, second left) and Lieutenant Colonel Williams (front, second right) with No. 1 Squadron Bristol Fighters, February 1918 Source: Wikipedia)

Lieutenant General Sir Harry Chauvel (front, second left) and Lieutenant Colonel Williams (front, second right) with No. 1 Squadron Bristol Fighters, February 1918 Source: Wikipedia)

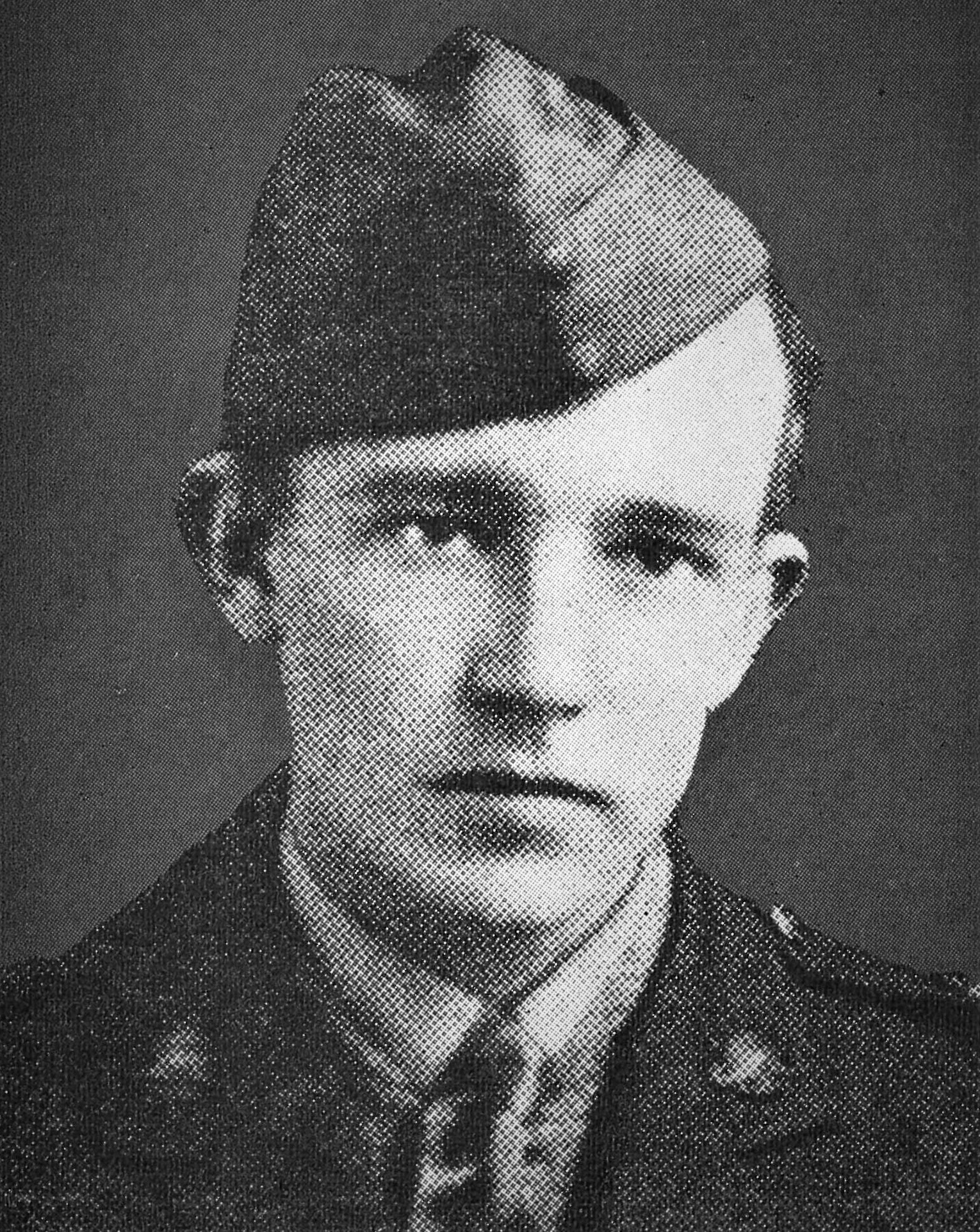

Former RAF Flying Officer Lt. Col. Richard Williams was a commanding forthright figure sporting a handlebar moustache. He retired as an Air Marshall and wrote in his autobiography:

The manager of the Blackburn Company in London, whose office was near Australia House, asked me to call and see him. When I did so he asked me if I would have any objection to replacing Kingsford Smith as a pilot for the Kangaroo…I said that provided he was Australian, it was no business of mine to say who should or should not be the pilot of a competing aircraft. In this case it was obviously a matter entirely for the people supplying it. I had not met Kingsford Smith, who was of course to become one of the world’s great pilots.11

Air Marshall Richard Williams

However as I was interested to know why the company desired a change and was informed that the pilot concerned had, with his friends, purchased an aircraft from the Government Disposals and was barnstorming in the country and, contrary to civil air regulations, was landing in fields not approved for that purpose. I was also told that he had found that he could insure his aircraft for an amount in excess of that for which he could replace it – and there had been some crashes. The Blackburn view was that this was undermining not only civil aviation control (they knew that the British government would be reluctant to prosecute a Dominion serviceman awaiting repatriation) but it was damaging aviation insurance, which was just getting established.

It had been stated by more than one source that Mr Hughes had prevented Kingsford Smith taking part in the race. I know of no foundation of this assertion.12

The Air Marshall was also unaware of any pilot’s application having been refused on the irrelevant grounds of lack of navigation skill.

He only wanted to say nice things about them.

The Blackburn Kangaroo lifted off from London’s Hounslow Aerodrome at 10 am on 21 November 1919. The fourth of six aircraft to leave, it’s departure delayed after frustrating delays waiting for more powerful engines.

Mackersay notes:

not only was Kingsford Smith absent from the crew, but so was Cyril Maddocks, possibly as a consequence of his own involvement in the insurance hanky-panky.13

Lt. Val Rendle was the only one of the three to fly the Blackburn aircraft. Ltn. Reg Williams flew as a co-pilot. Arctic explorer Capt. (later Sir) George Hubert Wilkins navigated, and Ltn. Garnsey Potts was their main mechanic. They left in good spirits circling three times before heading off over the channel. After leaving England the aircraft flew to France through appalling weather. Reg Williams recalled:

Lt Reg Williams c1919. Source: ‘The Greatest Air Race’ by Nelson Eustis.

It was bitterly cold all the time. On the first day out from England, we flew for about four hours in a snow storm with no means of navigating, just a compass.14

The following is an edited version from Nelson Eustis’ book of the 1919 Air Race tracing the Kangaroo’s journey from England:

The crew conversed by sending notes to each other via a pulley wire attached to the side of the aircraft. They put down at Romilly, 60km east of Paris.

Repairs were made and the flight continued. But so did the bad weather. They landed Lyons due to the continuing Mistral storm front.

The Kangaroo at the French base, Istres. From left: Reg Williams, a French flying instructor, Garnsey Potts, French Commandant. Source: ‘The Greatest Air Race’ by Nelson Eustis.

The Kangaroo at the French base, Istres. From left: Reg Williams, a French flying instructor, Garnsey Potts, French Commandant. Source: ‘The Greatest Air Race’ by Nelson Eustis.

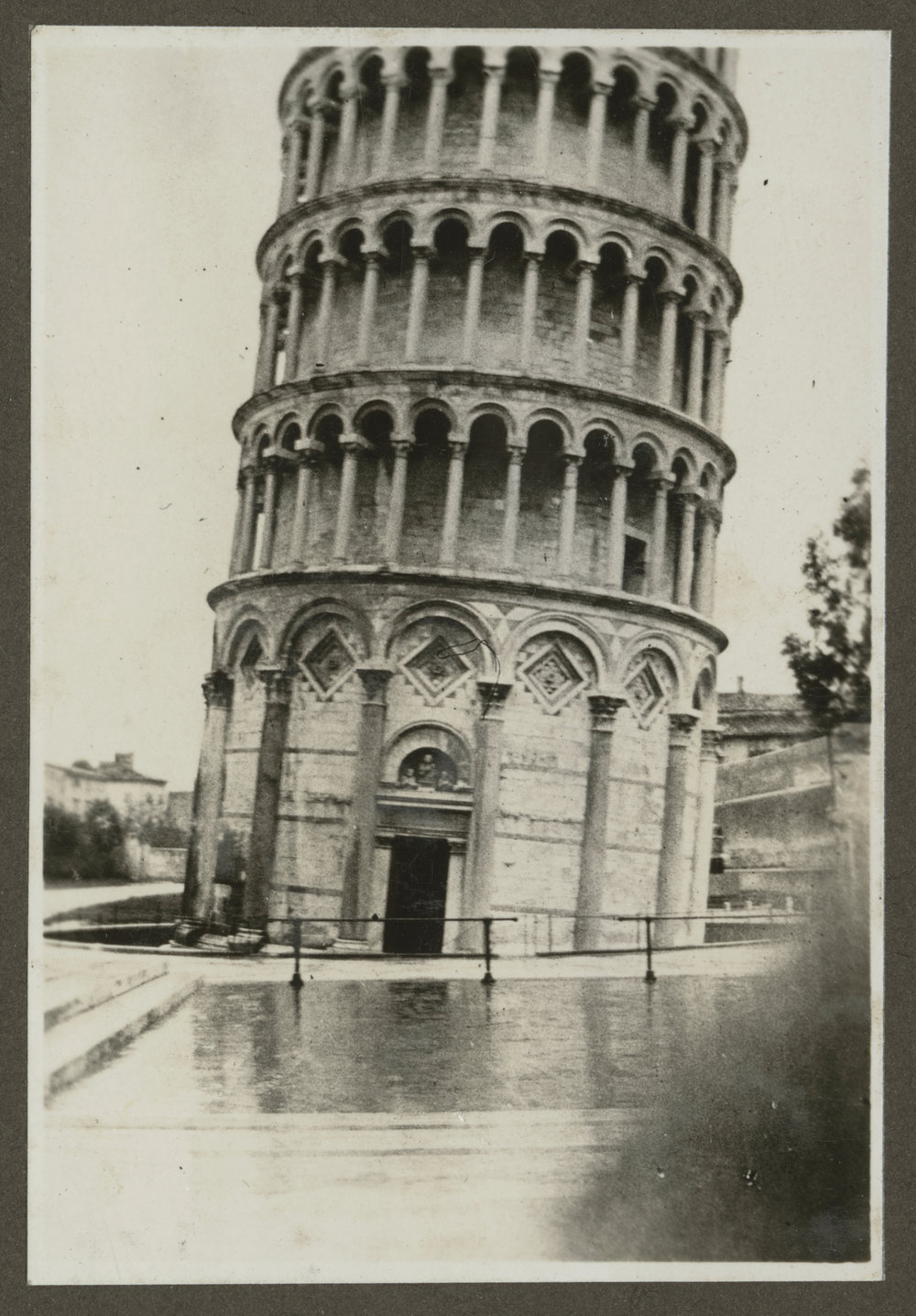

After flying to Istres for fuel the crew headed for Pisa, but returned again, due to the weather. landing at St Raphael, Frejus. From here they flew on again to Pisa. Over Antibes, mis-wiring (sabotage?) of one of the engines at St Raphael caused a magneto to fail.

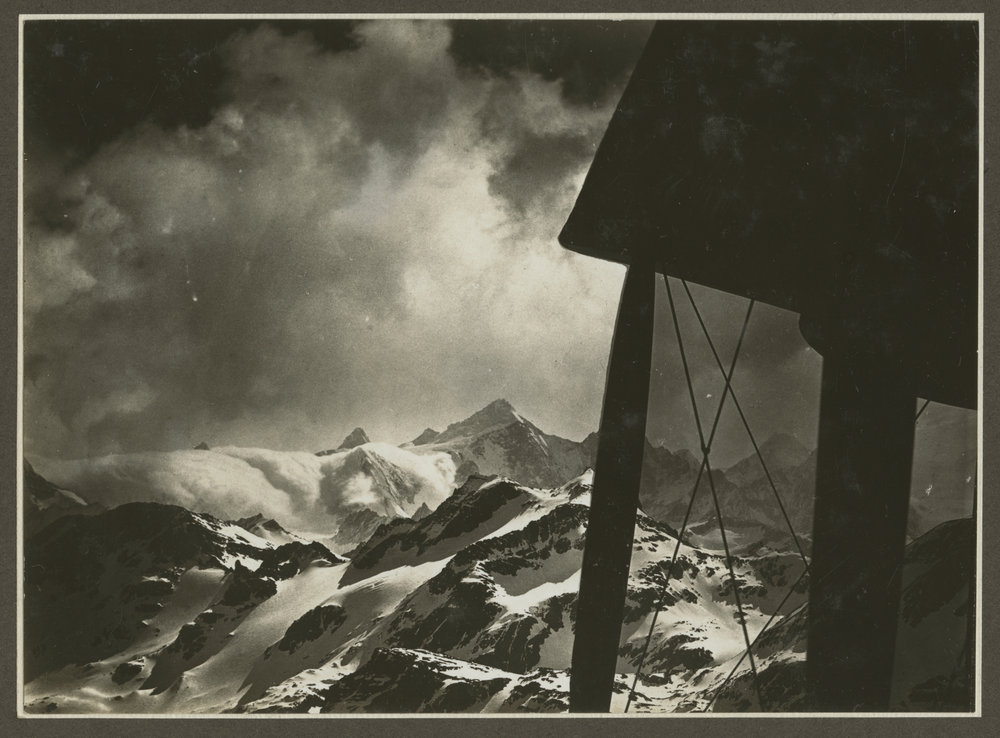

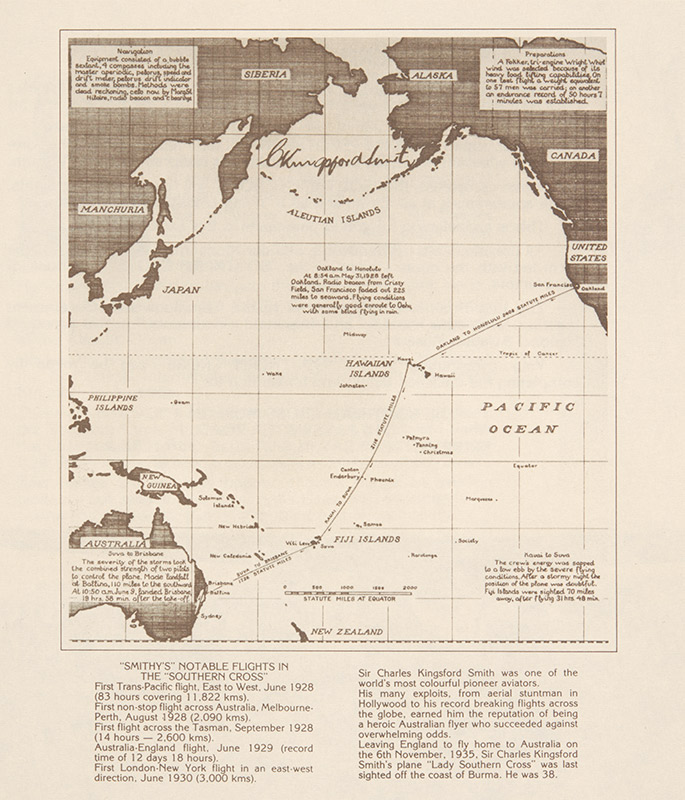

“Eastward the Alps reared up, serrating the horizon with a maze of glistening snow-peaks…” Ross Smith photographs Right: Leaning tower of Pisa Source SLSA PRG 18/9/1/10E

“Eastward the Alps reared up, serrating the horizon with a maze of glistening snow-peaks…” Ross Smith photographs Right: Leaning tower of Pisa Source SLSA PRG 18/9/1/10E

Despite this they made it to Pisa. But strong headwinds and more magneto trouble made it slow going to Rome. They hit heavy fog over the Apennines and had a near miss clearing the ranges to Taranto almost ending their lives.

After another forced landing, at Capua, they made repairs and the faulty magneto was replaced.

From here the weather changed and the Greek coastline in sunshine must have been a wonderful sight.

They reached their next destination, Crete, to find the airport flooded. The ‘Roo became bogged and was only disloged after Bulgarian prisoners were press-ganged to dig it out.

On December 8, the Kangaroo finally took off for Egypt. 40 miles out Potts passed a note – there was oil leaking, port engine, then it was confirmed “oil crankcase broken off”. With a huge amount of skill and effort the aircraft was wrestled back to Suda Bay.

Down to 800ft over the small town of Canea and losing altitude fast, Rendle risked switching on the damaged engine. The water jackets cracked and blew to pieces, fragments tearing through the fuselage. Luckily no-one was hit.

The crew were headed for a crash into houses, when Rendle, at the last moment pulled up and onto a landing field beyond. The ‘Roo clipped the roof of the last house, dropping into a 4ft ditch, bursting it’s tyres. Alarmingly, it kept heading for a heavy stone wall surrounding a mental asylum. An embankment in front of the wall ended ithe Kangaroo’s momentum and it finally halted, nose down, tail up.

The crew emerged shaken, but unhurt. After learning the engines would take months to replace, Williams and Rendle returned to the UK to make arrangements. En-route they received the disheartening news that the Vimy had arrived in Darwin. They traveled back to the UK via Corfu to obtain any news of airmen Howell and Frazer, and their Martinsyde aircraft, now lost over the Meditteranean.

The Kangaroo crash-landed in Crete. Note the registration letters G-EAOW, translated by the crew as: ‘England-Australia On Wings’ Source: ‘The Greatest Air Race’ by Nelson Eustis.

The Kangaroo crash-landed in Crete. Note the registration letters G-EAOW, translated by the crew as: ‘England-Australia On Wings’ Source: ‘The Greatest Air Race’ by Nelson Eustis.

The Hon. Mrs. Beryl Evans, daughter of Lt. Reg Williams was interviewed by Mackersay in the 90’s:

All his life Daddy [Reginald Williams] was extremely tactful and discreet about it…He was anxious not to say anything publicly that might harm the Kingsford Smith image. However in private, he would confirm almost exactly [air Marshall, no relation] ‘Dickie’ Williams’ version of events.’

Lt Reg Williams sole survivor of 1919 air race in 1969

Before her father died, Mrs Evans said, she had persuaded him to write for the family an account of his life, including the part he played in the 1919 race. ‘when he came to deal with Kingsford Smith and Maddocks he decided not to relate the full facts, just in case his memoirs ever got published. You see he only wanted to say nice things about them.’15

P.M. Hughes and dignitries presenting the Vimy crew with the race prize and honours in Melbourne.

P.M. Hughes and dignitries presenting the Vimy crew with the race prize and honours in Melbourne.

Years which the locusts had eaten

So what did Smithy do after this? Mackersay takes up the story:

While the Kangaroo had been making its slow way eastwards across Europe, Smithy, dejected broke and jobless, had decided to leave England. According to Reg Williams, as Beryl recalled, ‘Things had got a little too hot there for his and Maddocks liking. They decided to bail out, and took off for America.’16

Though this may have been a devastating and depressing turn of events, Smithy was more determined than ever:

My mind was filled with aviation to the exclusion of everything else.17

Attempts to sell the joyriding business in the UK failed. Smithy went to the USA at the end of November so short of money that he had to sell his only suit and travel in uniform. He had decided to try his luck in California, where he knew he would stay indefinitely with [his brother] Harold. When he arrived in San Francisco the week before Christmas, demoralized and still weak from scarlet fever, which had seen him compulsorily quarantined at Ellis Island in New York, Harold and his wife Elsie, and their teenage daughter were shocked by his appearance. But he soon rallied with their hospitality and the joy of reunion.18

Elsie wrote to Catherine Smith:

His whole heart is in flying and nothing else seems to interest him19

Like other ex-pilots Smithy was forced to find work where he could. In California he got paid to be an aerial stuntman for shows and the movie industry:

I very soon realised that my flying life would be short indeed if I continued at that game very long. The people who attended these exhibitions were too bloodthirsty for my taste. They wanted too much for their money. They weren’t satisfied with flying and wind-walking and other pleasant manoeuvres. I could see what they wanted. They wished to see a body carried off the field, and I did not want to be that body.20

Charles Kingsford Smith stunting for the movies, California, 1922. Kingsford-Smith travelled to Hollywood, among the stunts were wing-walking and hanging by his legs from undercarriages. (NLA 3723531)

Charles Kingsford Smith stunting for the movies, California, 1922. Kingsford-Smith travelled to Hollywood, among the stunts were wing-walking and hanging by his legs from undercarriages. (NLA 3723531)

Smithy wrote home:

…I am once more full of optimism after the last few black weeks I’ve had with this darned Australia flight falling through…However, dears, there’s lots of fight left in me and I have every other intention of coming home to you still by air- but from this country…I think I can get people over here sufficiently interested to back me…21

In another letter Mackersay notes Smithy’s driving motives:

‘If only I could do that job’ [cross the Pacific by air] Smithy wrote, ‘I would be able to justify myself in the eyes of the Australian people with a vengeance.’ The disgrace of the Blackburn affair was to haunt him for a long time.22

After failing in the US to get a wealthy backer, he secured passage on a ship home as a wireless operator. After trying his hand at various ventures on return to Australia, by 1927, he felt :

I had nothing to show for those ten years which the locusts had eaten. It was time to be up and doing. One had to do something to attract notice. It was a record-breaking era, so to speak, when a new record got your name in the papers, and generally made a success out of you.23

The big idea

Smithy continued in his auto-biography:

It was at this time that I met Charles Ulm. Ulm had similar ideas to mine. He was ambitious; he wanted to do something to make the world sit up; he had a good business head; in fact, he was a born organizer.

We began to talk of some big feat which would bring us what we wanted, fame, money, status. We wanted also to do something which would not only advance aviation and confound the skeptics, but something that would bring fame to our country.

…we had no money, no aeroplane, and no means of securing either. We were just three musketeers, Ulm, Keith Anderson and me- and our sole asset was a Big Idea.24

The Big Idea? Crossing the world’s largest ocean. The Pacific.

Promotional pamphlet for The Southern Cross Museum Trust. Source: National Museum of Australia

Promotional pamphlet for The Southern Cross Museum Trust. Source: National Museum of Australia

Follow the 1919 England to Australia Great Air Race Story:

Message to HMAS Sydney: ‘Very glad to see you…’ Ross Smith and the Great Air Race, 19191919 England to Australia Great Air Race: The contestants

Bibliography

Kingsford-Smith, Charles and Rawson, Geoffrey My flying life : an authentic biography prepared under the personal supervision of and from the diaries and papers of the late Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith. Aviation Book Club, London, 1939. Footnotes: 1-4; 17, 20, 23, 24

Mackersey, Ian Smithy : the life of Sir Charles Kingsford-Smith. Little, Brown & Co, London, 1998. Footnotes: 5-13, 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22

Centenary of WW1 in Orange. retrieved 19/03/20. Footnote: 14

Image credits:

Ellison, Norman and Kingsford-Smith, Charles, 1897-1935 Flying Matilda : early days in Australian aviation. Angus and Robertson, Sydney, N.S.W, 1957.

Eustis, Nelson The Greatest Air Race: England-Australia 1919 Adelaide, S.A. Rigby Limited, 1969.

Interesting websites

Video: Vickers Vimy replica at Caboolture ’94

1:72 scale model build of Blackburn Kangaroo