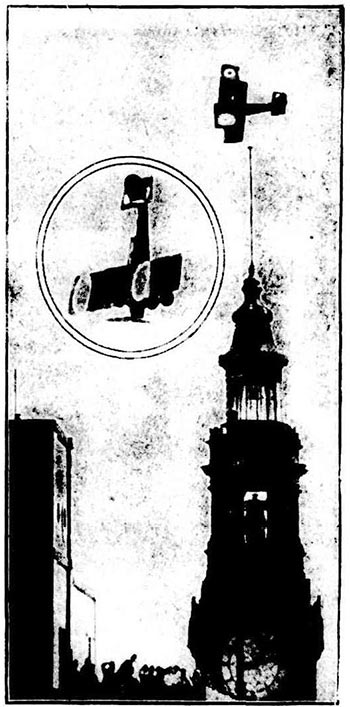

Few of the first AIF had the chance to show their dash in front of a home crowd but Garnet Malley did. This grainy photograph captures the Mosman birdman stunting over Martin Place in 1919.

Large crowds in the city during the luncheon hour yesterday were thrilled by the daring “stunts” performed by Captain Malley, M.C., in a Sopwith fighting machine. Approaching the city over Hyde Park, he accomplished three daring spiral dives. Over the city itself he flew so low that at times it seemed he must crash into some of the taller buildings; but he gracefully “hurdled” them all.1

He went on to wow kids at Blacktown2 and Penrith3 and crowds across country NSW4 with his playful aerobatics. Even a crash landing in a Benalla backyard smaller than his ‘Pup’ couldn’t stop him5.

AIRMAN ASTONISHES SYDNEY. Captain Malley, M.C., flew among the housetops of the city in aid of the Peace Loan campaign. The main picture shows him hovering over the flagstaff of the General Post Office tower. In the inset he is seen performing an exciting nose-dive.

— Barrier Miner, Saturday 11 October 1919

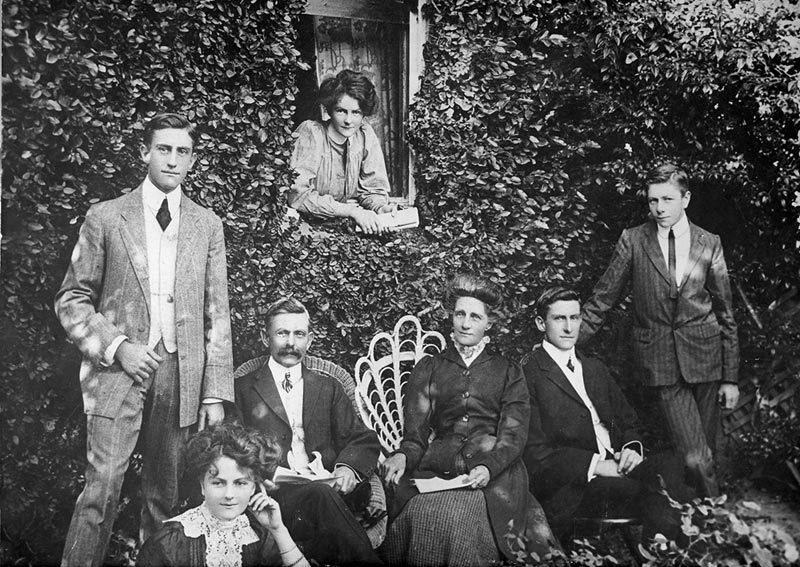

Garnet Francis Malley was born 2 November 18926 in Mosman to Francis Malley and his wife Clara Ellen (née Merritt). He was the fifth of six children. His older siblings were Charles, Clyde, Sylvia7 and Coral8; Roy was his younger brother9.

‘Sunrise’ Milk Can, Malleys Ltd., The Agricultural Gazette, Jan 1 1937, opp. page 49. (Source: From Farm to Factory)

Garnet’s father, Francis, an ironsmith from Gosford, established the firm of F. Malley & Sons Ltd in Sydney in 1884. They manufactured milk cans and machinery for the dairy industry before diversifying into builders’ supplies and hardware. On Francis Malley’s retirement in 1912, his eldest sons Charles and Clyde ran the company; they are listed as directors in 193510. Malleys Ltd became a sizable enterprise, with more than 3,000 staff nationwide in 1974. Alongside Malleys’ own building and enamelware lines were brand name products like Whirlpool washing machines and refrigerators, Hotpoint portable appliances and Esky portable coolers. Neville C. Malley is listed as vice-chairman in the annual report for 1964 but no Malleys appear on the directorate ten years later11.

When Garnet was born in 1892, the family lived in Cowles Road, Mosman12. Directories for later years show the Malleys at a number of different addresses, but always in Mosman.

As a Mosman Prep13 student, the young Garnet Malley would have been part of a prominent local family. As well as running a burgeoning business in the city, his father served two terms on Mosman Council14 and was a foundation member and trustee of the Warringah Bowling Club15. When Francis Malley died in 1932, the service was led by the Reverend D. P. Macdonald16 of Mosman Presbyterian Church. Reverend Macdonald would officiate when Garnet married Phyllis Kathleen Dare at the church17 on 25 January 192218.

Malley family, probably in Mosman, c.1906-1910. Coral (at window), and, left to right, Charles or Clyde, Sylvia, Francis, Clara, Charles or Clyde, and Garnet Malley. (Source: Peter Scholer)

Reflecting perhaps his father’s interests, Garnet was enrolled as a boarder at The School, Mount Victoria19, a private college in the Blue Mountains with a focus on business and commerce. His formal education was completed at Hawkesbury Agricultural College, Richmond.

In October 1915, when he signed up for the Australian Imperial Force at Victoria Barracks, Malley would have been familiar with both the ‘grit and dash’ of the Anzacs at Gallipoli and the casualty lists that accompanied Ashmead-Bartlett20 and Bean’s21 despatches.

Eyes “good” noted the examining medical officer.

Previous military service, offered Malley, was “Rifle Club Reserve, 6 months,” although perhaps not locally as no Malley appears in the Mosman-Neutral Bay Rifle Club Roll of Honour. His address at this time was the family home Elowera in Harbour Street, Mosman.

A month later Malley sailed for Egypt with the 1st Field Artillery Brigade, 12th Reinforcements, aboard His Majesty’s Australian Transport Wandilla. France was reached three months later, on April 1st, 1916, with landfall at Marseilles.

Source: Peter Scholer

Gunner was Malley’s rank. With the 101st Field Artillery (Howitzer) Battery he probably saw action both in Flanders and on the Somme22.

The Brigade’s war diary in late July notes that enemy targets are registered ‘to good effect’ with aeroplane observation.

He would soon have a seat in that gallery.

In April 1917 Garnet Malley transferred to the Australian Flying Corps (AFC) with the rank second air mechanic.

By mid-June he is attached to the first of three training squadrons (30, 29 and 34), and successfully negotiates at Oxford his introduction to the art and science of flying.

Selected candidates, after medical tests, were despatched to either No. I School of Military Aeronautics, Reading, or to No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics, Oxford, for a six weeks’ course, which included lectures on the theory of flight, aerial navigation, aero-engines, and construction of aeroplanes. In addition, practical experience was gained in aero-engines and in rigging, as well as in Morse-code buzzing, elementary artillery observation, bombing, compass, map-reading, &c. At the conclusion of the course the candidates were subjected to a written examination and, if successful, were sent to an elementary training squadron for instruction in aviation.23

R. A. F. School of Aeronautics, Oxford. Rigging and Instruction Shop. The aeroplane in the middle distance is a Sopwith Camel. © IWM (Q 27250)

Having won his wings, Malley is commissioned as a second lieutenant on 9 October 1917. A month later he arrives at No. 4 Squadron AFC24.

Alongside Malley is Harry Cobby, from Melbourne, a man who will become a firm friend as well as ‘the squadron’s most successful Hun-getter.’25

Captain A. H. Cobby DSO, DFC & Two Bars is the Australian Flying Corps’ leading ace and most highly decorated fighter pilot. His piece on ‘Aerial Fighting’ in the squadron’s history26 and an autobiography High Adventure capture the excitement of war flying without omitting the fear or the consequence. His mate Malley makes numerous appearances in these stories, sometimes, when less celestial matters are discussed, under the pseudonym George.

Sopwith Camel, Royal Flying Corps. (Source: Royal Air Force)

No. 4 Squadron, at an airbase near Birmingham, had begun that month its ‘strenuous and systematic preparation for active operations against the enemy airmen in France’27 with the delivery of its new service machine.

The Sopwith Camel was a single-seat biplane mounted with two twin-firing Vickers machine-guns and powered by a 130 horsepower Clerget 9B rotary engine28. Malley’s squadron were one of the first to be equipped with the new scout, produced by the Sopwith firm in 1917, and excellent work it did.

[The Sopwith Camel] was decidedly tricky to fly, but, when once a pilot mastered its eccentricities, he preferred it to any other. As was the case in all types, the machine was overloaded and expected to do the impossible ; but in the history of the Sopwith productions there is no machine which accounted for itself better than the Camel.29

Cobby described it as a wonderfully quick manoeuvering ‘bus whose dangers – knife’s-edge handling, feather-sensitive controls and purposeful instability – were an advantage to adroit and aggressive pilots.

…the guns on most scout machines are firmly fixed, so that the machine is but a gun-mounting, and it has to be pointed at your target in order to align your gun-sights. This all means that the more flexible machine has the advantage in a dog-fight.30

Albatros D.Va on the tail of a Camel. (The Vintage Aviator)

On 18 December 1917, No. 4 Squadron’s Camels, 18 in number, left their aerodrome at Castle Bromwich in three flights bound for France. Having rendezvoused at Saint-Omer, the squadron reached its new home at Bruay, 15 miles from the front line, on 22 December.

Over Christmas and New Year, pilots practised gunnery and formation flying over their new patch. Malley was assigned to “B” Flight.

Cobby notes that all were apprehensive, having had so little training. Cobby’s total flying time, both instructional and solo, was ‘about twelve or thirteen hours, and this on six or seven different sorts of aircraft.’

…daily publications in the press of the latest victories of the outstanding German aces, such as the Baron von Richthofen… filled our minds with rather an unhealthy opinion that the German was far and away a better equipped and a more efficient pilot than the average Britisher of the time.31

Active operations began in early January with offensive patrols and escorts of photo-reconnaissance machines.

Malley was promoted lieutenant on 9 January, and his first foray over the lines came the following afternoon on a patrol led by Captain Arthur O’Hara-Wood.

Malley’s machine on that mission was Camel B2488. It would serve him well during the German offensive that already loomed large over the horizon, but in January and February, the enemy was husbanding its resources and Malley’s targets were mainly trenches and billets.

On February 21st, while escorting two photography machines, Malley observed an enemy scout but it was ‘considerably higher than we were’32 and couldn’t be reached. A second opportunity to engage the enemy that day came to nothing when the German two-strutter dived away north-east to Lille.

Poor weather and obscuring cloud conspired to keep combats in the air to a minimum during this period but things hotted up considerably for Malley in March.

Map showing places mentioned in this story — view full-screen

On the 8th, “B” Flight accounted for two Albatros scouts west of Douai. Malley observed one go down out of control, the other in flames. On the 12th, an enemy fighter dived out of the sun and fired a long burst at the Australian patrol, before escaping east. On the 15th, Malley dived on two enemy two-seaters from 10,000 feet over Hautay, firing 100 rounds into one before it slipped away through the mist, seemingly in control, below the German observation balloons.

Malley’s first confirmed victory came the next day, and it was in a fight with Richthofen’s Circus.

The German airmen, as has heen explained, were avoiding battle until the desired moment; the plan of the British squadrons was to draw them on to engagement, and offensive-patrols swept the enemy’s front, searching for his strength, bombing his aerodromes, taunting him to fight, probing unceasingly to discover the main secret – the selected moment of his onslaught. It was expected that the first shock would be felt in the air. The patrols sought for that shock, for the first touch of the enemy’s battle-fleet. It might appear at any part of the front and at any moment. Each day after March 11th increased the strain. British battle-patrols multiplied their efforts.

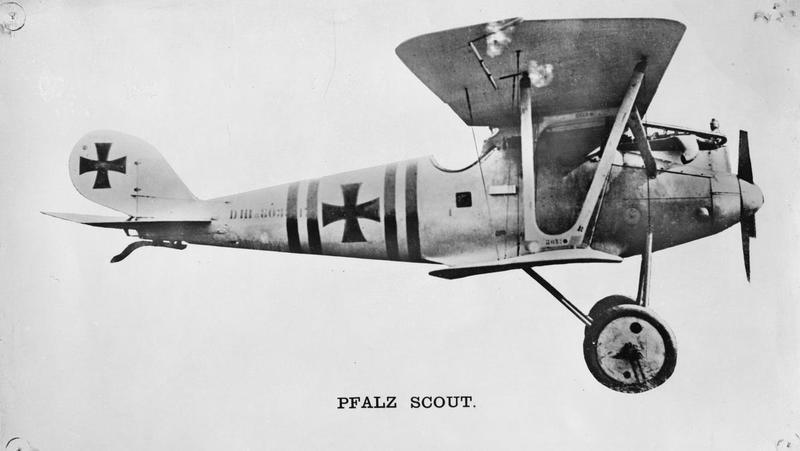

Pfalz D.III with 160 h.p. Mercedes engine. IWM Q 63860

Suddenly No. 4 Australian Squadron made the desired touch. In the morning of March 16th two flights, of five machines each, under Captain N. L. Petschler and Lieutenant G. F. Malley, set out to bomb Douai railway junction, Malley escorting. Petschler and two others were compelled to turn back by engine-trouble. Seven Camels reached Douai, and had just climbed to about 16,000 feet after dropping their bombs, when they were attacked from above by sixteen enemy scouts. It was Richthofen’s Red Circus, renowned as stormy petrels. The Germans dived upon the Australians in twos and threes and at once broke up Malley’s formation. In all twelve attacked in this fashion; the other four remained hovering above the fight, in order to prevent any recovery by the Camels for counter-attack. Lieutenants Malley and C. M. Feez, avoiding the first onset, fastened upon two red Albatros scouts which were diving together, and shot both of them down in flames.33

Frederic Cutlack’s Official History records Malley’s first victim as an Albatros scout but contemporary works34 have a Pfalz D.III falling to Malley’s guns at Annoeullin.

On the Australian side the fight was a desperate effort to escape, which barely succeeded. Lieutenant W. H. Nicholls, a newly-joined pilot, was chased down to the ground and just failed to reach home. He was forced to land in the German front line, and was taken prisoner. Lieutenant P. K. Schafer received the full force of the enemy’s opening fire; he dropped 10,000 feet in a spin earthward, followed by three red scouts, all shooting at him, and was saved chiefly by the Germans’ reluctance to continue the struggle at low height over the British lines. Schafer reached Bruay aerodrome with sixty-two bullet-holes in his machine, including several through the wind-screen in front of his face.

The report of Richthofen’s Circus in action over the Scarpe sector sent a thrill through local British air squadrons.

A few days later, on March 20th, Malley is appointed flight commander of “B” Flight when Captain Derwent P. Flockart leaves the squadron. He must have satisfied what his commanding officer Major W. A. McClaughry considered the essential criteria for the job.

It is imperative that a Flight Commander should be keen, and absolutely full-out to crash enemy machines, or attack ground targets from low altitude, as he is entirely responsible for the leading of his Flight, and pilots will quickly catch his spirit.35

The next day a terrific artillery bombardment at dawn heralds the Hun’s big push.

General der Infanterie Erich Ludendorff has concentrated his men and material in a massive attack that aims to split the Entente’s forces and drive the British armies into the sea. His stormtroopers make rapid gains in the heavy morning mists and soon the British soldiers on the Somme are in full retreat. Every aeroplane that can be scrambled takes to the air.

…the job consisted of getting to the line loaded up with bombs and ammunition, as fast and as often as one could, and letting the enemy on the ground have it as hot and as heavy as possible. The first sortie would commence well before daylight; the last would finish after dark. All this flying was done under 500 feet and our targets were point-blank ones.36

Camels of “C” and “A” Flight, No. 4 Squadron, at Bruay on 26 March 1918. The machines have just been prepared for further operations against the advancing Germans. In the background are Bristol Fighters of a Royal Flying Corps unit operating from the same airfield37. (AWM E01878)

Malley writes38:

Flights would leave Bruay for Bapaume, and begin bombing and ‘shooting-up’ enemy transport and infantry along the roads, around Vaulx-Vraucourt, Bapaume, and farther south. The weather at the beginning of the advance was indifferent for flying, being very misty, and heavy ground clouds made it difficult for pilots to gauge with accuracy the position of the German skirmishing line, especially while advancing so fast. Pilots would often fly for ten miles without seeing ground, and then would dive through dense clouds to try and pick up bearings, only to find themselves from fifty to a hundred feet above dense formations of Germans, who would hear a machine long before it appeared beneath the cloud, and would be ready to open fire on it directly it emerged from the mist. If the pilot were lucky, and were not vitally hit, he would immediately ascend into the cloud again and fly west, very often too far, and would have to feel his way back again to the moving line. Each day pilots had to judge for themselves the local situation.

After the first few days, the weather began to clear a little. Australian pilots who had fought in the infantry through the battles of the Somme, in 1916, felt outraged on finding the Germans not only again in possession of Bapaume, but advancing also on Pozieres, Albert, and the River Ancre.

24 or 26 March 1918, No. 4 Squadron, AFC — “B” Flight ‘1’, ‘7’, ‘4’ ‘2’ and part of “A” Flight, ‘D’, ‘F’ and ‘H’. (Photo: AWM E01877, caption A. Revell, ‘Sopwith Camel Squadrons’, 2011)

The Bruay aerodrome was a busy spot. Sometimes five squadrons of aeroplanes were lined out on the green – loading bombs and ammunition, checking sights, filling up with petrol, and overhauling machines. Pilots, chafing to get off to the line again, were all working with the mechanics and testing ammunition, which was of vital importance so that faulty rounds might not jam the guns in action. Each pilot arriving from the line would invariably have exciting news to impart to his comrades.

After dropping bombs, and using up their ammunition, pilots always made a point of lingering for a while to survey the spectacle of the one army advancing against the other. Details of this colossal movement visible from the air held one spellbound: villages for miles around all on fire; the smoke climbing from each blaze, and uniting at a great height to form a dense haze, pierced here and there by gun-flashes; roads teeming with transport; aerodromes, ammunition-dumps, Nissens-huts, and engineers’-dumps being dismantled, burnt, or shelled. One incident of six British tanks in retreat made a queer spectacle. Artillery, horse-transport, and motor-transport, a little farther back from the line, crowded the roads. Infantry were stolidly tramping the shell-riddled fields.

The morning of Saturday, March 23, sees the right flank of the British Third Army fighting a desperate rear-guard action around Bapaume. Camels from No. 4 Squadron are thrown into the fray, and Malley scores his second and third victories.

They were in two formations, under Courtney and Malley respectively, and each consisted of six machines. Courtney, flying at under 500 feet, led his formation in a bombing and machine-gun attack on Vaulx-Vraucourt village and the fields around it. There was no lack of targets for the airmen; the ground was swarming with German troops, and the roads were packed with other marching bodies and their transport. The five machines which first attacked spread dismay and confusion between Vaulx-Vraucourt and Lagnicourt, each firing between 500 and 600 rounds. Meanwhile, Malley’s formation, flying slightly above Courtney’s, intercepted an attack on Courtney from low-flying Albatros scouts. Malley himself shot down two of these Germans, both of which immediately crashed, and Scott defeated another whose fate was not seen.

The Albatros D.V with 180 h.p. Mercedes engine. Malley shot down two of these machines on 23 March 1918. © IWM (Q 63852)

There was no height for a machine to manoeuvre or to save itself from a bad spin. The effect on the infantry may be imagined – the rush down from the misty air of a flight of aeroplanes; the ear-splitting din of the propellers as the machines dived and wheeled and zoomed and dived again above the crowded road and over the village streets; the rush into ditches and holes to escape the searing sprays of bullets; the little broken-legged heaps of men and horses on the road; the collisions of bolting waggons; the new roar of more machines above, as aerial battle was joined over the heads of the low-shooting scouts; here and there the terror of a machine falling to wreck and death, perhaps in the narrow village street, perhaps in the field outside, but anywhere likely to crash upon some part of the crowd below; then the second rush, as the flight escorting the first attackers came down, in its turn, to repeat the first deadly whirlwind.39

Lieutenant Jack Weingarth, in Malley’s formation, describes to his parents a patrol on 25 March:

Yesterday I had a front stalls seat at the big battle that you must be reading about in the papers. I was in the thick of it at about 2000 feet; had a most exciting time, due to the attentions of ‘Archie’ and numerous other iron and lead rations. We had to drop pills on our dear friends below. It was absolute hell let loose; fires burning everywhere, oceans of smoke, roads choked with transports and troops.40

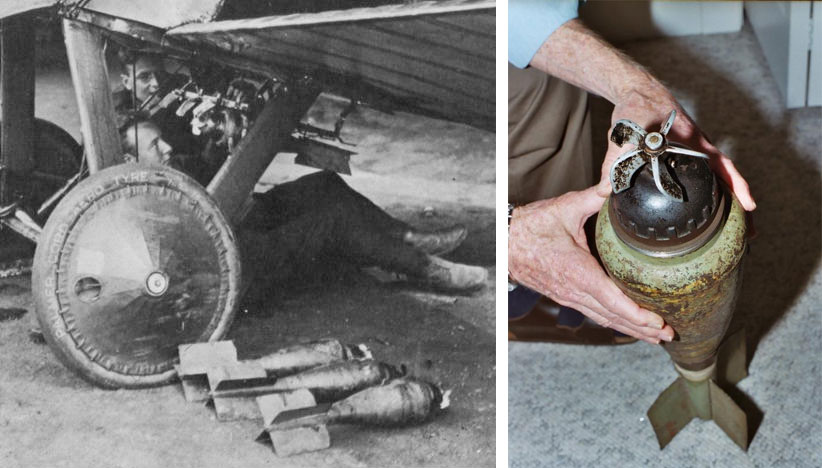

Left: Cooper bombs being fitted to a bomb rack. Each Camel carried four bombs. Right: US-made Cooper bomb (courtesy John Alcorn, World War I Modeling Mailing List).

On the 26th, Malley is promoted captain but is fortunate to see out the day. The squadron’s record book has begun detailing the weight of ordnance delivered against the massed German troops, and this is Malley’s report.

Dropped one bomb on motor-transport and troops on road Bapaume-Ervillers (8.30am) from 2,000 feet. Observed fire start. Was attacked by Albatros scout and two triplanes, which drove me practically on to the ground and damaged my machine. Fired about 400 rounds at troops in fields and in trenches north-west of Bapaume from about 15 feet. Saw many fall apparently hit and the remainder scatter in all directions.41

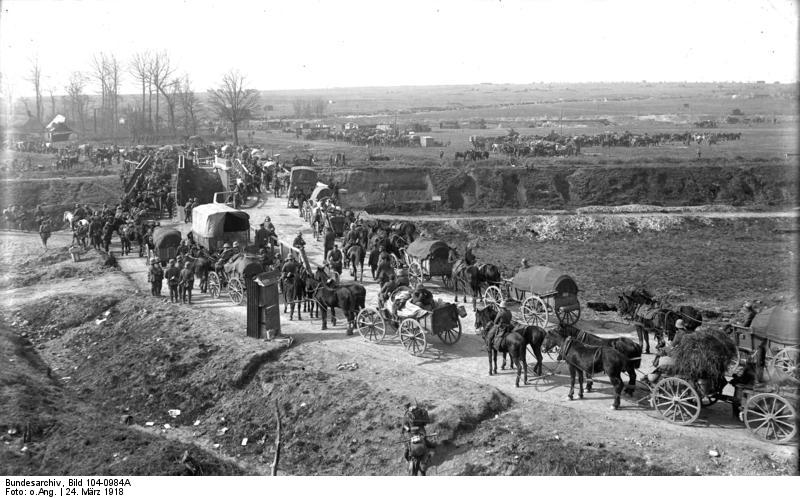

24 March 1918. Bei Etricourt, Truppen auf Landstraße. German transport moving up between Peronne and Bapaume. (Source: German Federal Archive [Deutsches Bundesarchiv] Bild 104-0984A)

Low flying attacks came thick and fast for the remainder of the month, with pilots flying several sorties a day. ‘Very nerve racking work at these heights,’ said Lieutenant Ernest R. Jeffree42, a pilot in Malley’s “B” Flight. It was not long, said Cobby, before all were starting to show signs of strain.

My principal trouble was that I could not eat, but champagne and brandy with an odd biscuit seemed good enough. It was nothing more than overstrain, nervousness, and a mixture of fear and high tension. Added to this was the feeling that the war was going the wrong way and that our efforts were wasted. The line literally jumped forward miles daily and there did not seem to be sufficient troops or guns to stop the German advance.43

A German transport column moving forward along the Albert – Bapaume road, March 1918. IWM (Q 60474)

But after a spectacular start, Operation Michael began to lose momentum. By the tenth day, with the enemy halted about Albert, Corbie and Villers-Bretonneux, No. 4 Squadron was relieved from ground-strafing to resume its normal offensive patrols around Lens. They had done their bit.

…while it was the heroic infantry of outnumbered British and French divisions which held up the enemy advance – and the Australian divisions played a glorious part in the later stages – it was principally the untiring exertions of the airmen in delaying, damaging, and disheartening the enemy’s reserves, and throwing his whole transport system out of gear, which enabled the Allied infantry to succeed.44

Thwarted on the Somme, Ludendorff followed 4 Squadron north to Flanders and attacked between Bois-Grenier and La Bassée at dawn on April 9. Malley led a flight of five to bomb bridges over the river Lys before the Germans could use them. Lieutenant Jack Weingarth describes the mission45:

We had to fly as low as 200ft on account of the heavy ground mists and the clouds of smoke from shells and burning towns and villages; in fact, the whole country was ablaze. Of course, at 200ft, we had to fly through the barrages, and it is really wonderful that we were not hit by shells which were going over in thousands. We had a pretty hot time getting back. Our leader was shot in the leg, the bullet finally smashing his watch on the dashboard; my machine was riddled with bullets…

It was a last ride over the lines with Malley for stalwart Camel B2488, but its pilot fared better.

A squadron orderly dressed the wound and sent him to the closest field hospital in Major McCloughry’s car. According to Vern Knuckey, Malley was a favourite among the air mechanics in his flight: ‘As he sat in the back seat of the car waving to the boys everyone hoped he would soon return.’

Battles of the Lys, April 1918. Estaires in flames at night. Estaires fell on April 11, after fierce street fighting with the 5th Durhams and 6 Northumberland Fusiliers of the 50th Division. Made by German official photographer. (IWM Q 55258)

They weren’t disappointed. Malley stayed in hospital for two days before insisting he get back to the squadron. Six days later, he was on the flying roster again. The bombing reports from Malley’s sortie don’t survive, but it is clear they didn’t have a decisive result. A British reconnaissance flight at 6.00 p.m. confirmed that the Germans were across the River Lys, some 8 kilometres from their starting line.46

Malley was patched up at No. 23 Casualty Clearing Station, returning to the Squadron on 11 April. It was the day Field Marshal Douglas Haig gave his famous order:

There is no other course open to us but to fight it out. Every position must be held to the last man: there must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause each one of us must fight on to the end.47

By the end of April, this second German drive had also been held and a new line secured, across which the Australian airmen maintained a constant menace, bombing trains, supply dumps and billets, and machine-gunning the roads all about.

In return, Gotha night-bombers targeted their airfield. The squadron escaped injury but when the town of Bruay came under the guns of German heavy artillery, they had to pull back some twenty miles, to Clairmarais North, on April 28.

Cobby writes of their regret at leaving the small shop – half estaminet, half private house – of Madame Brunêt:

We were much nearer the coastal towns at the new ‘drome, but it was with mixed feelings that we said goodbye to Bruay. Malley, Gillis-Watson, Bo Lamplough and others of us regretted the loss of the amenities we had become accustomed to at “Madame’s” and both she and Leonie shed tears over us before we left…

George Malley and I always were the favoured ones of the household and “Zheorge”and “Ah’ree” (which was the nearest they could get to Harry) could do little that was wrong.48

Sharing the airfield at Clairmarais North was No. 74 Squadron, Royal Air Force, with its renowned flight commander.

To Capt. “Mick” Mannock (of No. 74 RAF and afterwards Major and CO of No.85 RAF), 4th Squadron AFC owes a large amount of its success… he took upon himself the task of making all the pilots around him keen and aggressive. Several talks of his to the Australian pilots there were responsible for some fine aggressive shows against the enemy, and numerous combined affairs were successfully carried out. I regard Major Mannock’s character and spirit as the finest I have met in the Air Force. He was practically blind in one eye, yet he could recognise various types of enemy aircraft when the average person could barely see machines. No matter how great the odds, Mannock always managed to extricate his patrol without losing machines. I was extremely pleased to see that the Air Board officially recognized him as the greatest of all British pilots, with the wonderful record of seventy-two enemy machines officially confirmed as destroyed. Unfortunately, this very gallant officer was shot down in flames and killed just a few months before the Armistice; but his wise teachings and splendid example bore abundant fruit after his death amongst those pilots who were privileged to be associated with him in his work.49

In May the squadron’s sector widened, with patrols from Armentieres to Lens, but ‘far beyond these boundaries the pilots sought for hostile aircraft and favourable ground targets.’50

Twin Vickers machine-guns mounted in the ‘hump’ of the Sopwith Camel.

Lieutenant Jeffree, in a formation led by Malley, accounted for two scouts early in the month.

On 2 May, when out on patrol, I saw an Albatros Scout over Bailleul, and left the patrol to dive down on it & open fire. I chased it down to about 500 feet, saw it side-slip, and finally crash into a hill. It was confirmed by another pilot of the patrol.

Next morning I saw yet another Albatros Scout, dived on it and opened up an accurate burst at quite close range. I pulled up, dived and fired again, and saw it crash also. Both had been lone machines harassing our ground troops. Soon after the strain of flying up to 4 patrols a day finally caught up and I was sent off and admitted to hospital in a state of exhaustion.51

On 7 May, as part of a larger patrol, “B” Flight had three indecisive combats with 12 enemy scouts.

On 9 May, in the early evening, just south of Ypres, Malley’s party of five Camels was dived on by nine enemy scouts. In the dogfight that ensued, the patrol claimed a Pfalz D.III that broke up in the air, crashed and burst into flames near Voormezeele. Cutlack, in his Official History, says it was Malley who shot it to pieces52 but the victory was shared by the patrol.

Poor weather and low visibility restricted flying on the 10th, but the next day saw Malley and “B” Flight return to the fray.

A great joint bombing attack by No. 4 Australian Squadron and No. 110 (Naval) Squadron, R.A.F., was planned for the evening of May 11th on the ammunition-dumps at Armentieres. Malley and Petschler, each leading flights of five, were the escorts. Shortly after 7 o’clock the bombers blew up a big dump and started an extensive fire. As the airmen were about to turn homeward, a cloud of German scouts – about thirty in all – attacked from the east. In Petschler’s formation Lieutenant H. G. Watson destroyed one Pfalz, and Petschler shot down an Albatros out of control, but the flight lost Lieutenant O. C. Barry, whose machine fell in flames from a fierce duel. Malley’s formation also drove down an Albatros. It was the longest air battle Australian airmen had hitherto fought. In the light of the evening sun it was often difficult to tell friend from foe. Inevitably formations were completely broken up and scattered over a wide area of sky. As eventually the raiders, individually or in little groups, turned homeward, they were dismayed to find everywhere a smother of white fog below them. Setting their course by the sun – still visible above the horizon at their great height – and by the distant fire of the Armentieres dumps, they flew west, descending slowly. “We just guessed where home was,” said Malley, “and as we finally dived into the cloud we expected to have to penetrate only a film of haze. Instead, we found it was thick fog for a thousand feet through to the ground. As we entered the fog, all machines immediately lost sight of one another. The first sign of ground was a blurred mass only a few feet under the machine – too late for some, unfortunately, to pull out of their dive. It was impossible to select a landing-place, and night was fast coming on. Some did not know whether they were descending to sea or land. The only thing to do was to slow the machine down, shut your eyes, and hope for the best. In my case I hit the top of a tree, somersaulted, and landed upside down, but whole and no bones broken. The machine in the fog and darkness looked a pitiable wreck.”53

On their return, not a single airman found his aerodrome. Six of No. 4 Squadron’s machines were damaged beyond repair. Two RAF pilots were killed.

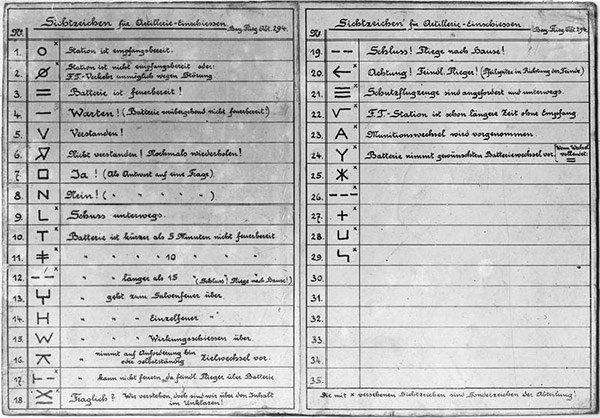

By now so many German observation machines were working this sector that RAF brigade headquarters instituted the “stand-by” patrol. Stations on call would be scrambled when German machines were heard transmitting to the gun batteries for which they were spotting. A white arrow on the ground at the listening station directed the Allied airmen towards the enemy.

Reproduction of a document captured in an aeroplane in April, 1918, showing the wireless signals and ground signals used with the 294th (Bav) “Flieger Abteilung”. (IWM Q 35769)

On the 15th, Captain Malley and Lieutenants Finnie and Jeffree responded at 6.45am to the signal of enemy artillery machines between Voormezeele and Kemmel and Bailleul and Merris. The patrol drove off six two-seaters doing wireless, Malley diving on one over Doulieu.

…a long burst at close range was fired into the E.A. [enemy aircraft] which immediately turned east and glided very steeply, emitting volumes of smoke, and crashed in the vicinity of Bac St. Maur, smoke still pouring out of the machine.54

The German machine was Malley’s fourth confirmed victory.

The patrol was back up at 9.05am to chase off wireless machines between Merris and Neuf-Berquin, and later that afternoon between Kemmel and Messines.

On each of the next three days, Malley led large flights to attack what was thought to be their nest. Ninety bombs were dropped on La Gorgue aerodrome near Estaires.

During the raids, the patrol chased five Albatros scouts from Armentieres to past Wervicq; Malley and Lt Alexander Rintoul attacked a two-seater over Estaires to no visible effect; and, Lieutenants W. S. Martin and R. C. Nelson downed two of four triplanes over Bailleul. The patrol also attacked enemy balloons, four of which were pulled down, and they shot up the roads between Merville and Estaires.

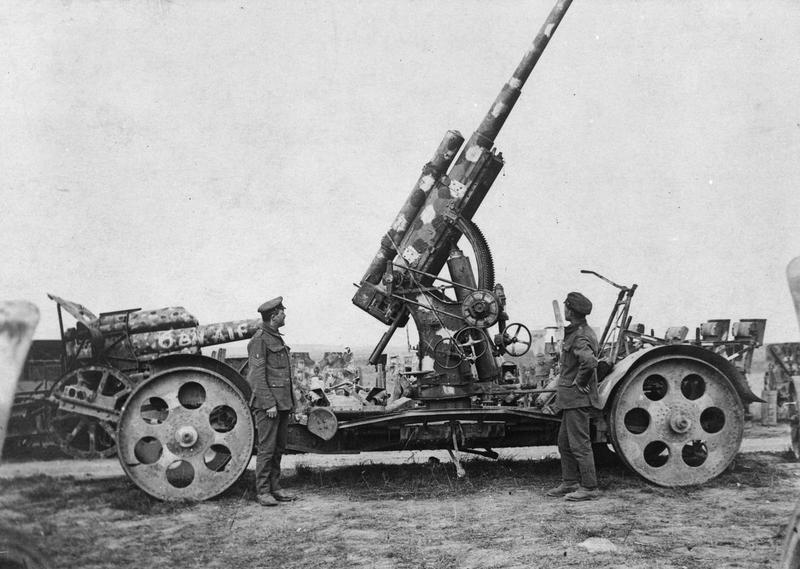

German long-range anti-aircraft gun captured by the British in the Amiens sector, Longueau, Somme. 29 August 1918. © IWM (Q 80022)

Out on his second patrol of the day on May 18th, Malley was wounded in the cheek by shrapnel from an anti-aircraft round55 but the injury was slight and he was back in the air on the 22nd.

About this time, “balloon-strafing” came into vogue at No. 4 Squadron, and Cobby claimed, near Neuve Eglise, their first.

Observation balloons were stationed at 3,000 or 4,000 feet, tethered to the ground and protected by machine guns and anti-aircraft artillery (“Archie”56). Even with incendiary bullets the gas was hard to ignite and downing a balloon took a lot of shooting while running a gauntlet of ground-fire and keeping a sharp eye out for protecting scouts.

German observation balloon. Image from The Vintage Aviator collection.

There were other hazards too. On patrol with Malley on 22 May, Lieutenants G. Nowland and A. Finnie, diving on the same balloon, collided in the air and spun to the ground near Neuf-Berquin. Malley followed them down as far as the flak allowed57 but he knew they had no hope.

Malley would claim his balloon on May 30th.

…on that afternoon sixteen machines, in two flights under Malley and Cobby, swept the region of the Lys above Armentieres. After the whole force had bombed the Bac St. Maur dump, it flew on south and westward, and at Estaires the two leaders destroyed a balloon each within five minutes, while two more balloons were hurriedly pulled down… In this attack the Australians, with premeditated cunning, appeared from the German side of the balloons, and the watching balloon-hands apparently mistook them at first for friendly machines.58

Cobby has the unofficial version of this story59 which sees him, Malley and Watson strike out on their own, having agreed in advance a rendezvous with the patrol. Giving the larger formation enough time to be noticed over the line, they struck out in the opposite direction. When they were well over the German side, they worked back west and surprised two Albatros scouts by diving out of the sun from the east. Having crashed the two enemy machines, they turned on the balloon line and attacked three in succession. Two went up in flames.

Left: shrapnel bursting near a German observation balloon. (IWM Q 54459) Right: German observation balloon falling to earth in flames. Note observation officer descending by parachute. (IWM Q 54468)

On June 1st, at 14,000 feet, Malley took on a black Pfalz D.III scout with white tail near Bac St Maur when coming to the aid of a straggler in his formation. The engagement is described on Army Form W3348, Combats in the Air, submitted by Malley on his return.

While on Offensive Patrol I saw 2 Pfalz Scouts some distance East of my formation. Lieut. Rintoul strayed from our formation and these machines both attacked him. He then dived with one Pfalz Scout on his tail. I followed and attacked the second Pfalz Scout firing 200 rounds from about 15 yards range. He tried to dive away but machine became out of control and broke up in the air, a wing parting from machine. This machine was observed to break up by Lieut. Ramsay and other Pilots of formation.

2/Lt A. Rintoul never made it back to base and was posted missing. He was later reported a Prisoner of War60.

With the Pflaz scout and the balloon destroyed in May, Malley had six confirmed victories. It afforded him the title ‘ace’.

Of more immediate import, he was alive. With Cobby, Captain Walter B. Tunbridge and Major McClaughry, Malley was one of the only remaining pilots of the original roster that had landed in France in December 191761.

Pilots of “A” Flight, Clairmarais North, 16 June 1918. Left to right: Lt J. S. M. Browne RAF; Lt C. R. Burton; Lt C. S. Scobie RAF; Lt R. G. Smallwood; Capt A. H. Cobby DFC; Lt R. King; Lt R. F. McRae RAF; 2/Lt A. H. Lockley; Lt W. A. Armstrong RAF. Three of the six pilots in flying gear are wearing Sidcot suits. (AWM E02661.)

June and July proved the most successful for the squadron since their arrival in France. More than 60 enemy machines were shot down for the loss of two men killed in action and two taken prisoner.

We felt, writes Cobby, on top of things.

We had a great deal of self confidence by this time, so much so that we regarded odds of two-to-one against us as being about an even contest. This was particularly so when those of us who had been together for so long, such as Malley, King, Watson, Trescowthick and one or two others, went out together. We had so much knowledge of each others’ tactics and such perfect understanding, that we would have tackled almost any number of aircraft.62

On 2 June, Malley forced a balloon down south of Estaires at 6.30am but fog prevented him from seeing if it caught fire. On 3 June, near Outtersteene, Malley and 2/Lt A. T. Heller attacked a DFW bi-plane from close range, both getting off about 150 rounds before they lost it in the clouds. On 5 June, Malley dived on a two-seater near Ypres but had to break off when attacked by five enemy scouts. He harassed an anti-aircraft battery near Bailleul on 7 June, and, on the 9th, gave chase to a high-flying enemy machine from Bailleul to Armentieres but could not get up to its height.

A fortnight’s leave to the UK followed.

Pilots of “B” Flight, Clairmarais North, 16 June 1918. Front row: Lt J. H. Weingarth; Lt O. B. Ramsay; Lt H. G. Watson; Lt H. F. Davison RAF; Major F. I. Tanner. Back row, left to right: Lt J. W. Milner RAF; Lt R. Sly; unknown Australian officer; Lt R. Moore RAF; Second Lieutenant A. T. Heller. They are pictured in front of a Camel with two 25lb Cooper bombs and a belt of ammunition. (AWM E02496)

Unfortunately for us, it means Malley is not part of a fine set of portraits of squadron personnel taken on 16 June, like this photograph of “B” Flight of which he was Flight Commander. He also managed to miss by a week the King’s visit to 4 Squadron’s aerodrome on 10 August, the subject of another fine image.

Official recognition, however, awaited him in England. On 22 June, Malley was awarded the Military Cross. The citation – published in the London Gazette – reads:

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. When on offensive and low-flying patrol he attacked one of two hostile scouts, which eventually turned over and fell out of control, being seen to crash by another pilot. Later, a general engagement ensued with four enemy scouts, one of which he attacked, with the result that it fell completely out of control and crashed. Prior to this occasion he had also shot down out of control another hostile machine. His courage and able leadership have resulted in his patrol carrying out excellent work under the most adverse conditions.63

A letter to his mother – printed in the Parkes and district Western Champion – dates from this time.

I have been very well treated in the Flying Corps and have got three stars and a Military Cross, and I am now a blooming Flight Commander! To-day I had lunch with the High Commissioner for Australia, his Secretary, General —, and another very important person in a very swank club in London. Oh, yes, thanks, I am getting along famously. Please do not worry about me. I would not change with the ground grubs for worlds. One can see much more of the war from the air gallery seats.

The letter assures his mother of his well being, but may suggest a complication with the wound in either his foot or face.

I’m afraid they bungled the cables up terribly. I was not gassed and we are ever so far away from it […] I was in hospital for [a bout?] of septic poisoning. It has now healed up beautifully and I’m going back to France tomorrow.

Malley was back at Clamarais North to fly combat patrols on 25 and 26 June. Cobby tells of a fine stunt on the 27th.

Malley, another pilot named Crosse, and I went off the next day on what we called a special mission. We did not always disclose what we were going to do on these occasions, in fact we did not always know ourselves, but relied on something turning up. If things were quiet might only give the troops on our side some stunting to cheer them up, the main idea being that we worked off surplus exuberance. On this trip, however, we went over to an enemy drome on the outskirts of Lille and “left cards”. There were two Albatross scouts on the tarmac, both painted black and white so we commenced by setting them on fire. We then chased everybody away that put their noses into sight, and finished up by flying across the aerodrome with our wheels on the ground and firing into the open doors of the hangars, hoping that we would burn up a few more machines, but we were not successful in this. We then crossed Lille at some twenty feet above the roof-tops, waving our hands to the people in the streets, and quite a number of people waved back. We were fired at by the forts around the town, but we kept right down on the ground all the way back, twisting this way and that so that enterprising field gunners and people with machine guns could not get much of a shot at us. As a matter of fact we were pretty safe, as they would not expect the enemy to come coursing across country from behind them, especially so low down.

It was amusing to see odd batches of troops come out of billets and hutments and start to wave at us, and then go to ground like startled rabbits when they realised that our machines belonged to the enemy. We may have hit some with our wheels here and there. We usually zoomed up after passing them and looked down over our tails as they lay on the ground, and facetiously blew kisses to them. They thought us quite mad I expect, but it must have had a demoralizing effect on them to see us sporting round their territory without hindrance.64

Moonlit nights saw German bombers over Clairmarais repaying the airmen in kind. It was, says Cobby, ‘one of the most nerve-wracking experiences of the war.’

At night, machines were pegged out in the open in case of direct hits on hangars, and personnel had to sleep some distance from the aerodrome.

The intensity of these raids was so demoralizing that we were ordered to pack up camping kit and move away some miles and sleep under hedges, but several of us stayed behind, and although we did not completely get used to the nerve-racking din, a few bottles of Bass helped us to get in a fair amount of sleep.65

The bombing saw No. 4 Squadron move at the end of June from Clairmarais to Reclingham, 30 km south. Captain Edgar J. McCloughry writes66:

On the day before our move 29.6.18., the C.O.’s leave fell due and Capt. Malley took temporary command; he was loved by all and everyone helped him as much as possible in the moving.

Like Cobby, McCloughry pays tribute to British ace, Mick Mannock.

We left for the new aerodrome at Reclingham by flights, the whole of the 74th Squadron turning out to see us off, and I could not help feeling then that most of my experience was due to 74 and Mannock.

The new aerodrome, shared with the scouts of No. 2 Squadron AFC, was sited on top of a hill, and tents were pitched for pilots in an old orchard. The weather and surroundings were good, and the change of scenery was a welcome one, although the ablutions shed didn’t come online until 27 July.

As acting CO, Malley was nominally responsible for an order on 3 July that ‘pilots must on no account stunt over the Officers’ or Other Ranks’ quarters at low altitude.67’ It is hard to imagine it being directed at anyone but Cobby.

Major Wilfred Ashton McCloughry M.C., Officer Commanding, No. 4 Squadron, AFC, in front of his Sopwith Camel aircraft. 6 June 1918, Clairmarais North. (AWM E02656)

A greater responsibility for managing machines and personnel may be why the squadron record book details only eight patrols for Malley in July.

Of note among the bombing and ground-strafing reports is one for July 14th, when Malley and two Sopwith Dolphins attack a pair of Albatros two-seaters east of Steenwerck, Malley firing about 200 rounds at one of these without apparent effect.

Of greater affect was a ‘special mission’ with Cobby.

The journalist Keith (later Sir Keith) Murdoch had visited No. 4 Squadron back in March and his glowing reports of ‘Australia’s most dashing boys’ were widely published. Malley was among those celebrated.

The steadfastness of the Australian soldiers to each other has many fine exemplifications in the squadrons. For instance, yesterday, after downing a Hun, the Fitzroy man fell behind his formation. Immediately the Boche put up a powerful and heavy “Archie” barrage, hoping to hold him until the Fritz scouts arrived. It was a ticklish moment for the airman. One shell burst a few feet above him, and others came very near. A Mosman boy detached himself from his homeward flight, and joined the Fitzroy boy, in order to help him. All got safely home.69

Cobby suggests this was mild compared to the purple prose that drew on them plenty of friendly flak.

Those of us who were still in the squadron remembered the teasing that Tab Pflaum had had to put up with as a result of the many columns that had been devoted to the “Baptist Boy Hero” and certain of his exploits. Then Garney Malley had been covered as the “Mosman Air Marvel” and in long articles, episodes of his early life were referred to, how he used to intrepidly breast the surf at Manly at an early age, as he was now breasting the heavens!70

When Murdoch visited Reclinghem in July 1918, ‘we decided that the unsuspecting Keith should be the lamb to be led to the sacrificial altar for war correspondents generally.’ Murdoch wanted to see the lines from the air, and Cobby and Malley arranged for him to be taken up by a flight commander with No. 2 Squadron, Captain Frank Follett, in an unarmed two-seater called ‘Sophie’.

Follett was instructed to to go well over the lines, then throttle off his engines for as long as possible to allow anti-aircraft artillery to have a good go at him. Cobby and Malley would escort ‘Sophie’ and demonstrate aerial combat to the passenger.

Everything worked according to plan, except that Follet nearly crashed taking off. The leg reach to the rudder bar was particularly long in machines of the “Sophie” type and as Follet was built on small lines he could not get enough leverage on the rudder to stop the bus from swinging as he started off and it described a big circle. He knocked over some crates of 25 lb. bombs on the tarmac and nearly collided with the end hangar, but it got off all right in what the press used to call a “clambering swerve”.

On the way to the lines, we poked our wingtips in alongside the ear of Murdoch in the rear seat, to let him see how safe flying was, and perhaps to inspire in him a little nervousness in preparation for “Archie” before crossing the lines at about twelve thousand feet, quite a nice height for effective shooting. Of course Follet was expected to use all his gumption to avoid being hit, but there was of course a fair amount of risk.

Shrapnel bursting amongst reconnoitring planes. Picture taken over the tail of a leading machine / taken by Capt. F. Hurley, August 1917 – August 1918. (SLNSW PXD 23/no. 45.)

As soon as “Archie” opened up, Malley and I climbed into the gallery to enjoy the spectacle and presently we saw “Sophie’s” nose come up slowly as Follet shut off his engine and gently stalled the old bus. Then he pulled it up to proper stall and held it there until a tail slide was imminent, before letting it fall over sideways and recovering control about four hundred feet lower down. In the meantime, Archie was giving them a good going over and the air was black and brown with bursts of high explosive. After about fifteen minutes of doing everything one shouldn’t do for bodily comfort, Follet made back to the lines and then Malley and I in our Camels staged a mock battle with the Two-Seater.

We dived straight at it until we could see Murdoch duck his head as we shot across him, and took it in turns looping around the machine, rolling alongside it and then closed on it again. We then flew sedately homewards making signs to Murdoch appropriate to the occasion. Back at Reclinghem we asked him how he enjoyed things and what kind of chance he thought we had of finishing the war in a blaze of glory as his paper had so often inferred. He took it all extraordinarily well and though he looked a bit pale around the gills, insisted that we adjourn to the mess and have one on him. Naturally we duly honored the invitation as we rather liked his style and later came to value his friendship.

Murdoch’s column appeared in Sydney’s The Sun on 11 July 1918.

IN THE AIR – AUSTRALIA’S FINE WORK – MOSMAN BOY’S ADVANCEMENT

I spent to-day with an Australian scouting squadron, which during June made a new record for the war. The squadron flew 1913 hours, dropped 10 tons of bombs, and destroyed 26 Hun fliers.

The present leader of the squadron is a Mosman boy, an engineer student, with 10 Huns to his personal credit. This fair-haired, blue-eyed youth, left Australia as an artilleryman, and now leads a patrol daily with great skill and audacity over the German lines, swerving, diving, and “zooming” amidst the clouds to escape the enemy’s anti-aircraft guns, but going straight towards the enemy when he sees a Boche plane…

I went aloft the line with [Cobby] and the squadron commander [Malley] in their scouting machines as escorts. Beneath was a maze of trenches and a desolation of shelled areas. All the earth was pock-marked, and we could see charred villages and deserted townships which had been burnt. No movement was discernable, and there was little shelling and few troops marching.

The chief impression from the ground was the brooding melancholy of the deserted but still lovely farmlands; but in the air these scouts were the very epitome of life and daring. They flew at tremendous speed up and down, diving, climbing, turning, and swooping round, above, under, and alongside the double-seated plane in which I travelled. Their command of the skies equalled that of the eagles, for they hurled themselves in all directions with an apparent mastery of air…

Hitherto, having travelled on only modest slow flights, I have thought of air work in terms of discomfort and danger. In future I will always think of it in terms of extreme skill, coupled with sublime daring, for this scout’s mad flight leaves an indescribable impression of skilled recklessness.71

The Hôtel Christol, Boulogne – Ernest Proctor © IWM (Art.IWM ART 3324)

Another incident around this time gave Cobby a story, but at Malley’s expense. Cobby was returning from leave and Malley made for Boulogne to meet him.

George [Malley] had met me at the boat and told me the Town Major, a cheery soul, had introduced him to a French family who would make his short stay pleasant while he waited for the car to return. Some four hours or so later, about 1 a.m., Boulogne was subjected to one of the Hun’s periodical air raids. All street lights went out, alarms sounded, and presently the bangs and explosions of bombs and anti-aircraft guns informed us that the show was on.

The car was outside the club, so hastily gathering up my kit I beat it for the Rue de Renard to pick up George, and found to my horror that his friends’ house was on fire, and that the one next door (a terrace of three storied dwellings) had taken a direct hit with a pretty big bomb and had practically disappeared…

We found George at the end of the street, safe and sound, with his coat and field boots on, but his breeches were over his arm, whilst his nether portions were swathed in a blanket. We parked him in the back seat under the big angora goatskin travelling rug and made out of town. He told us his experience as we went along. “It was a good night,” he informed me. “You missed a bonzer party. I was entertained with true French hospitality and drank buckets of bubbly, sang all the songs I knew, played the gramophone and generally enjoyed things.’‘

“They suggested that I might like a snooze and should stay the night and showed me upstairs to a bedroom on the top floor. I heaved off my field boots and my pants and crawled into bed, and presently faded gently away. But it seemed that I had hardly fallen asleep when something went off with a terrific bang. I could hear whistles being blown and people crying out “Le Bosche!”, “Beaucoup Bombard!” and so on, but I was quite comfortable and much too sleepy to move. Then something like ten thousand tons of bricks fell on the house next door and the next minute I was looking out into space. The wall had disappeared and so had the house next door. Recollecting something about lightning never striking twice in the same place, I settled down again. I awoke with a choked feeling and sitting up I saw the room was full of smoke and sparks. The remains of the house next door were on fire, and it seemed that the lower floors of the house I was in were also alight. Grabbing my belongings and wrapping a blanket around my nakedness, I rushed downstairs, but had to put my field boots on to cross the lower flight as it was smouldering steadily. I made for the end of the street hoping to get a lift around to the club, and apparently missed you.” With this explanation George went to sleep under the rug, wrapped up in his blanket. He was still there when the car came to a stop on the tarmac at Reclingham outside the orderly room. The Adjutant, or Recording Officer, was the only officer on parade and he had just wheeled the men off the “falling in” ground and they would presently pass us…

Old George, who knew nothing whatever about drill, and could barely give a command correctly, was nevertheless a stickler for the right thing, and he too had obviously just awakened. As the troops came opposite the car, the adjutant gave them the “eyes right” and slung the appropriate salute in the direction of the car. George, befuddled by sleep, but nevertheless true to his principles, got quickly out of the car and drawing himself up rigidly to attention, returned the salute. He was greeted with an expression of blank amazement on the fact of the adjutant, then someone tittered and in about a split second the whole crowd were laughing hilariously. George was astounded until the corporal driver leaned out of the front seat in a hearty whisper informed him, “No pants on, sir.”

George ducked back into the car with his khaki shirt tail blowing in the breeze, much more quickly than he got out.72

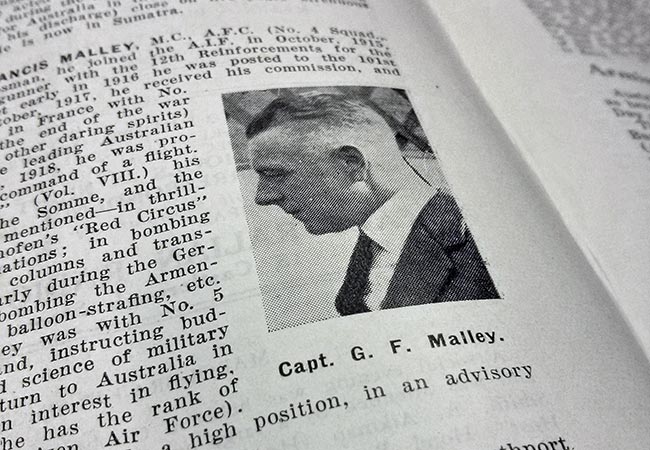

On 3 August 1918, Malley left the squadron for Home Establishment.

Cobby writes:

We had been together from the start and had seen the fighting strength of our unit turned over many times. We had been in practically everything of importance that had occurred, both on the ground and in the air, and his leaving was a wrench. So far I had been lucky enough not to be sick or wounded, but he had had a couple of knocks. In March he had received a bullet through his leg, but had kept on going and on another occasion, had been hit by shrapnel. I was wondering how long it could last. But the fatalistic outlook that had become so much part of our natures, just refused to be concerned with the possibility of being knocked out of the sky. One’s great concern was whether one was to be confined to endlessly flying and fighting, and whether there would be any other sort of existence for us. I saw Malley off from Boulogne in the accepted and time-honored custom.73

In a tour of duty amounting to some seven months on the Western Front, Malley had flown 125 sorties for a total of 166 hours and 15 minutes of war flying. Practice, test and travelling flights accounted for another 24 hours and 10 minutes.

In England, at Minchinhampton, Gloucestershire, Malley took command of “C” Flight at No. 5 (Training) Squadron, AFC. Pupils sufficiently advanced in their training to fly Camels were transferred to his class for advanced instruction.

Captain Malley with his all-white Sopwith Camel F.1 aircraft, serial number E7259. (AWM A03880)

To ready them for combat, cadets would “scrap” with their fighting instructor. These mock fights, says Cobby, were more of a strain than flying in France. For safety, instructors painted their aeroplanes in distinctive colours and designs to distinguish themselves in the air from the novice cadets74. Malley’s white Camel E7259 became a familiar sight at Minchinhampton.

Captain Malley in his distinctively-painted Sopwith Camel. (Source: Peter Scholer)

Later, when Cobby returned to England as a fighting instructor, he too painted his Camel white, but added black checks.

Garnie Malley and I used to collaborate a lot in demonstrating that Camels could be thrown about the air in the closest of flying, without danger, if the pilots knew each other and their machines.75

Both pilots asked a number of times to be sent back to France, but even stunting over the wing commander’s Avro as it approached the aerodrome proved a wash-out.

We immediately tucked tucked our wings in behind his and throttled back and were so close that he would not land. We then looped round him from the side, then from the rear, and then on each side of him just about his top plane. He finally went down and landed, then as he touched the ground we “leap-frogged” over him and taxied in front of him. When he reached the tarmac he was boiling…76

The Sopwith Camel F.1 flown by Captain Garnet Malley whilst he was “C” Flight Fighting Instructor with No. 5 (Training) Squadron AFC at Minchinhampton, Gloucestershire. Illustration Norman Clifford, published in the 1981 edition of Cobby’s High Adventure.

For a few days in early October 1918, Malley assumed duties of Squadron Commander when Major R.S. Brown, Commander of the Station and No. 5 (Training) Squadron, proceeded on leave.

A recently discovered photograph of Malley and his Camel. (Source: Warbirds Online)

Malley then attended the Special School of Flying at Gosport, located across the harbour from Portsmouth, before proceeding to RAF Hounslow for a course of instruction on the Sopwith Snipe. ‘As they are a machine with a fine reputation,’ notes the recording officer, ‘everyone is very anxious to fly them.’

Training continued after the armistice of 11 November 1918, at a lower pitch but still with its attendant dangers. Some, like Jack Weingarth, lost their lives after this date.

Minchinhampton, England, April 1919. General Sir William Birdwood congratulating Capt G. F. Malley MC, Officer Commanding (OC) C Flight, No. 5 (Training) Squadron, AFC. Foreground, left to right: unidentified; Major Roy Phillipps MC & Bar DFC, OC, No. 6 Training Squadron; Lieutenant Colonel W. O. Watt OBE, CO, 1st Australian Wing, AFC; General Birdwood; Major R. S. Brown, OC, No. 1 Two Squadron Station, Minchinhampton aerodrome; Capt Malley. AWM D00473.

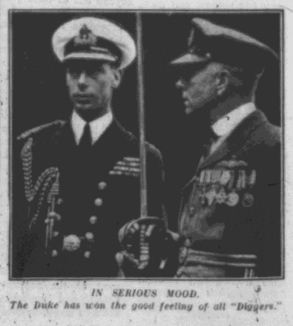

Those who survived had an opportunity to express their exuberance on Anzac Day. A feature of the Australian pageant in London on 25 April 1919 was an aerial show that is never likely to be seen again. Huge crowds gathered to see the Prince of Wales accompanied by General Birdwood take the salute of the AIF in front of Australia House on the Strand, and Malley was among the AFC airmen who took full advantage of the freedom of the skies.

Cobby, who flew below the overhead wires three-quarters of a mile down the Strand, before zooming up just short of Trafalgar Square, describes the scene:

At 2.30 about fifty or sixty machines were jockeying around the sky over Australia House, and more kept on arriving. Aircraft were looping and rolling and spinning everywhere, but the libations of the morning had added more verve than sense to the manoeuvres. As the head of the column approached the saluting base, there was a mad scramble to pass the Prince, and some of us went down into the Strand in order to do the thing properly. It was probably the most foolish thing I have ever done…78

In October 1919, in recognition of his work at Minchinhampton, Malley was awarded the Air Force Cross, a decoration awarded for ‘valour, courage or devotion to duty whilst flying, though not in active operations against the enemy.’

Aboard HMAT Kaiser-i-Hind, 1919. From left, Captain Garnet Malley, Captain Edgar Davies, Major A. Murray Jones, Lieutenant Norm Trescowthick and Captain G.C. Wilson. This photo appears in the 1981 edition of Cobby’s ‘High Adventure’.

The Australian Flying Corps departed Southampton for home on 6 May 1919 aboard the P&O liner Kaisar-i-Hind. Smuggled aboard in an oat sack was No. 4 Squadron’s mascot, the French orphan boy, Henri ‘Digger’ Heremene.

Very few people on board failed to see the sun rise on the morning of June 9th, for with the dawn came the first glimpse of Australia. Naturally, after two or three years of wandering around Europe, there was much excitement amongst all ranks at the first sight of their native shores.79

The ship’s final port of call was Sydney, on Thursday 19 June. She cleared the Heads at 7.30am and berthed at 9.45 am at Woolloomooloo where the Anzac airmen were met by a capacity crowd of family and friends.80

Malley’s career after the war was no less adventurous or distinguished, and he retained a prominent position in aviation circles.

The Daily Telegraph, 1 July 1925. Defence ‘Planes Arrive At Richmond. How the Richmond air base is being established. THe first three ‘planes of this important extension of the Australian Air Force arrived from Point Cook yesterday. The subjects are: No. 1 – The first of the S.E.5a’s taxi-ing to the hangar. 2 – Flight-Lieut. F. W. Lukis, officer in charge of the base, whose machine was the first of the fleet to arrive. 3 – His machine, a D.H.9. 4 – Flight-Lt. G. Malley, who, with No 6, Flight-Lieut. Les Holden, arrived in charge of two single seater scouts. Both are Citizen Force officers with distinguished war records. No. 5 – A group of the rank and file at Richmond. Soon there will be 58 permanent air craftsmen at the base.

In 1925 Malley was appointed to a commission in the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and flew one of the first aircraft to their newly established station at Richmond.

RAAF Richmond, New South Wales. The first CO of No. 3 Squadron. Flight Lieutenant Lukis (left) with Flight Lieutenant Stephen and Flying Officers Malley and Mulroney. 1925. Source: Roylance, Derek (1991) Air Base Richmond, RAAF Base Richmond: Royal Australian Air Force, p.29.

He was vice-president of the Australian Flying Corps Association from 1925 until 1928, and helped organise the search for the missing Southern Cross.

He was aviation consultant to Australian National Airways (ANA) and a director of the firm for a short time.

From right: Squadron-Leader Malley, Flight-Lieutenant Ulm, Wing-Commander Wackett, Squadron-Leader Kingsford Smith. 1929 ‘AT THE INVESTITURE BY THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL AT ADMIRALTY HOUSE.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 4 June, p. 14, viewed 9 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16562453

The Daily Telegraph, Sydney, 1927. See also The Argus, Melbourne.

He had a number of ceremonial roles, representing the air forces in 1927 for the Australian visit of the Duke and Duchess of York, and again at the opening of the first Parliament House building in Canberra. From 1929 to 1931 he was Honorary Aides-de-Camp to the Governor of NSW.

The 1930s saw Malley and his wife Phyllis leave Australia for China, a remarkable story still shrouded in some mystery.

Malley was aviation advisor to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, leader of the Chinese Nationalist government, operating at Nanking, Hankow, Chungking and Chengtu, and had a role with the Chinese air force in the early stages of the war with Japan. General Chen Chia-shang, air force commander-in-chief, said the invaluable assistances he rendered would be long remembered.81 Chris Coulthard-Clark’s paper, Garnet Malley and the RAAF’s Chinese connection, is recommended reading for more on this story.

Malley returned to the RAAF active list in July 1940 for duties with the Combined Operational Intelligence Centre (COIC), General Headquarters, Southwest Pacific Area. After the war, General Douglas MacArthur personally complimented Malley on the work of this section and he was awarded the US Legion of Merit in 1948.

From 1944 Malley was a staff officer in the Security Service in charge of the Chinese section at Canberra.

Squadron Leader Garnet Malley and Charles Stuart, New South Wales, ca. 1930. Fairfax Corporation. http://nla.gov.au/nla.pic-vn6256044

On leaving service in the late 1940s, Malley maintained an active social and sporting life. With his wife and son, Maldon, he sailed the Pacific in his yacht Royal Flight and bought a copra plantation in Fiji. The society columns of Australian newspapers kept their readers informed of his and Mrs Malley’s social engagements.

Funeral of Captain Garnet Malley, Lauthala Bay, Fiji. (Source: Peter Scholer)

Garnet Malley died on 20 May 1961, aged 68, and was buried at sea.

Of his eclipse from the historical picture, historian Dr Chris Clark writes:

There is […] little doubt Malley was one of the more notable and colourful figures of both the Australian Flying Corps and the early Royal Australian Air Force. The highly unusual elements of his career provide a legitimate reason for seeking to document his record, and preserving it for posterity. As a general rule, Australia has been slow to recognise the worth of many of the achievements of its early airmen.82

Malley is remembered in Mosman today on the east face of the War Memorial and on the Mosman Church of England Preparatory School Honor Roll.

This post marks another tribute.

Reveille, November 1932, p.10.

Select bibliography

Cobby, A. H. & Clifford, Norman 1981, High adventure, Kookaburra Technical Publications, Melbourne

Coulthard-Clark, C. D. 1997, Garnet Malley and the RAAF’s Chinese connection, Air Power Studies Centre, Fairbairn, A.C.T

Cutlack, F. M. 1941, The Australian Flying Corps : in the western and eastern theatres of war, 1914-1918, 11th ed, Angus & Robertson, Sydney

Fraser, Alan 1992, ‘A month with 4 Squadron Australian Flying Corps’, Cross & Cockade International Journal, vol. 23 no. 1

Molkentin, Michael 2010, Fire in the sky : the Australian Flying Corps in the First World War, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, N.S.W

Richards E. J. [1920?] , Australian airmen : history of the 4th Squadron, Australian Flying Corps, Bruce & Co., Melbourne

Websites

Chris Clark, ‘Malley, Garnet Francis (1892–1961)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, accessed 8 October 2013.

Newspaper articles tagged Garnet Francis Malley 1892-1961, Trove, National Library of Australia

First World War Diaries, No 4 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps – AWM4, Sub-class 8/7 – Australian War Memorial

4th Squadron, Australian Flying Corps – Ian Miller

The Diary of Australia’s Air Ace – Group Captain A. H. Cobby, Sunday Mail (Brisbane, Queensland)

Australian Society of World War One Aero Historians – membership includes access to the database Australian Airmen of the Great War 1914-18 and other resources including a journal.

Notes

1 1919 ‘PEACE LOAN.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 17 September, p. 11, viewed 8 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15860655

2 1919 ‘FLYING FEATS..’, The Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate (Parramatta, NSW : 1888 – 1950), 20 September, p. 6, viewed 9 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article86117538

3 1919 ‘A Pup in the Air.’, Nepean Times (Penrith, NSW : 1882 – 1962), 20 September, p. 2, viewed 9 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article86193527

4 1919 ‘Captain Malley.’, Goulburn Evening Penny Post (NSW : 1881 – 1940), 4 October, p. 4 Edition: EVENING, viewed 9 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article98904873

5 1919 ‘AIRMAN’S STRANGE LANDING.’, Advocate (Burnie, Tas. : 1890 – 1954), 3 September, p. 4, viewed 9 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article66576739

6 NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages

7 Sylvia married Oscar Marx Scholer. 1911 ‘Family Notices.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 7 January, p. 12, viewed 21 September, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15221566

8 Coral wed Dr G. W. Mason, of Parkes, son of Dr and Mrs. T. Mason, of Wyrallah, Mosman. 1913 ‘Family Notices.’, Western Champion (Parkes, NSW : 1898 – 1934), 6 November, p. 33, viewed 21 September, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article116832468

9 Roy Neville Malley would also enlist, and attain the rank of air mechanic in the Australian Flying Corps. He appears in this photo of B Flight, No. 8 Training Squadron on the Australian War Memorial website.

10 From Farm to Factory, viewed 21 October, 2013

11 Malleys Ltd, Annual report and accounts, Mitchell Library, SLNSW

12 Sand’s Sydney & N.S.W. directory, 1892

13 Garnet and his younger brother Roy both appear on the Mosman Church of England Preparatory School Honor Roll (1914-1918).

14 Alderman Francis Malley twice represented the north ward, February 1896 to January 1898 and February 1903 to 1905.

15 1932 ‘MR. FRANCIS MALLEY.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 29 June, p. 15, viewed 21 September, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article16921965 Of interest too is the fact that a representative of the Chinese Consul-General attended the service.

16 The Reverend Donald Peter Macdonald served Mosman as a member of the NSW State Legislative Assembly. He also served in France as chaplain with the 2nd Division Artillery from 1917. http://mosman1914-1918.net/project/blog/keith-anderson-memorial

17 Today this church, on Belmont Road, is known as Scots Kirk.

18 1922 ‘WEDDINGS.’, Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW : 1895 – 1930), 5 February, p. 17, viewed 7 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article128218488

19 A fellow student would also fly in the First World War. Air Vice Marshal William Dowling (Bill) Bostock CB, DSO, OBE went on to become a senior commander in the Royal Australian Air Force.

20 1915 ‘AUSTRALIAN HEROES.’, The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), 8 May, p. 5, viewed 6 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article10412578

21 1915 ‘GALLIPOLI.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 2 July, p. 9, viewed 6 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article15602272

22 I found it difficult to interpret Malley’s service record during this period but the unit war diaries suggest action both in Flanders and France. He is linked with 101st Howitzer Battery in Reveille, November 1932, p.10.

23 Cutlack, The Australian Flying Corps : in the western and eastern theatres of war, 1914-1918, Appendix 5.

24 At this time in the United Kingdom the squadron was designated 71 (Australian) Squadron, Royal Flying Corps (RFC) but it reverted to its original title on 19 January 1918.

25 Richards E. J., Australian airmen : history of the 4th Squadron, Australian Flying Corps, p.17. Cobby is credited with 24 enemy aircraft destroyed, 5 sent down out of control and 13 German field observation balloons shot down.

26 A transcript is available online via the Pandora archive.

27 Richards p.10.

28 The Historical Aviation Film Unit has excellent footage of reproduction Camels in flight.

29 Cutlack, p.407

30 Richards, p.62

31 Cobby, A. H. & Clifford, Norman 1981, High adventure, Kookaburra Technical Publications, Melbourne, p.35.

32 No. 4 Squadron’s war diaries (AWM4, Sub-class 8/7) are the source for much of the detail regarding patrols.

33 Cutlack, pp.224-225. In his preface, Cutlack says he is indebted to, among others, Malley and Cobby ‘for reading the manuscript and for their notes, which were of great value, on obscure points.’ Presumably Malley provided some input on these actions.

34 The Camel file by Ray Sturtivant and Gordon Page.

35 McClaughry in Richards, Australian airmen, p.56.

36 Cobby, p.50.

37 Cobby, p.38.

38 Quoted in Cutlack, pp. 234-235.

39 Cutlack, p.231.

40 Weingarth, Gerald 1996, ‘Camel Pilot: Lt Jack Henry Weingarth, 4 & 5 Sqn AFC’, Cross & Cockade International Journal, vol. 27 no. 1, p.7.

41 Cutlack, p.437.

42 Interview with Lieutenant Ernest R. Jeffree / Formerly of No.4 Sqn., A.F.C. – Australian Society of World War I Aero Historians, 1967 journal, p.55

43 Cobby, p.50.

44 Cutlack, p.237.

45 Weingarth, p.8.

46 Michael Molkentin, Fire in the sky : the Australian Flying Corps in the First World War, p.244.

47 A copy of this order can be viewed online, at National Library of Scotland, Acc.3155/125, f.80

48 Cobby, pp.36, 60. Malley plays a central part in the story of a wedding party for Madame’s seventeen year old son, whose marriage is la consequence d’une inconsequence.

49 Cobby, Aerial Fighting, in Richards, Australian airmen.

50 Richards, p.17.

51 1967, ‘Interview with Lieutenant Ernest R. Jeffree’

52 Cutlack, p.278.

53 Cutlack, p.278-279.

54 Royal Air Force communiqué

55 This wound (“second”) is reported in Sydney’s Sunday Times on 16 June. 1918 ‘N.S.W. WAR CASUALTIES.’, Sunday Times (Sydney, NSW : 1895 – 1930), 16 June, p. 3, viewed 6 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article123129635

56 From Cutlack’s Glossary, p445. “ARCHIE” : The name universally employed by British airmen to designate the anti-aircraft gun on either side. It was given in Flanders in early 1915, and followed a habit which has existed among gunners in the navies and armies of all nations since cannon were first used in battle. Grandma (the first British 15-inch howitzer behind Ypres), “Quick Dick” (for a high-velocity gun), Percy (an early name for a 4.7-inch naval gun in the field), are other examples. Why an anti-aircraft gun was named “Archibald” is a matter of mystery, though it is said that our own “archies” – since for a long time they could never hit the air anywhere near a German machine – owed the title to the music-hall song “Archibald, Certainly Not.”

57 This detail is contained in Malley’s letter to a friend of Nowland, Miss Winnie Hinton, of Southend on Sea, transcribed in Lt Nowland’s Red Cross Wounded and Missing file.

58 Cutlack, p.285.

59 Cobby, p.63.

60 The Australian War Memorial has a photo of Lt Rintoul in 1919 having returned from captivity in Germany.

61 Cobby, p.58.

62 Cobby, p.68.

63 London Gazette, Issue 30761, published 21 June 1918. The citation probably refers to the two Albatros scouts he downed on 23 March 1918 during the German spring offensive, the previous victory being the Pfalz D.III shot down in flames over Annoeullin.

64 Cobby, p.69.

65 Cobby, p.73.

66 Captain Edgar J. McCloughry writing in 1919 a review of his experiences in France whilst serving with No. 4 Squadron AFC.

67 Fraser, Alan 1992, ‘A month with 4 Squadron Australian Flying Corps’, Cross & Cockade International Journal, vol. 23 no. 1, p.7.

68 Presumably Lt G. Nowland, a tent-maker from Fitzroy. On 8 June 1918, Nowland downed an enemy scout west of Douai. The unit war diary shows he was part of a large flight led by Capt D. P. Flockart that included Malley.

69 1918 ‘ANZAC FLIERS.’, The Maitland Daily Mercury (NSW : 1894 – 1939), 13 March, p. 5, viewed 6 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article122649356

70 Cobby, pp.84-85.

71 The column can be found in syndicated form with different headline in Trove. 1918 ‘AUSTRALIAN AIRMEN.’, The Maitland Daily Mercury (NSW : 1894 – 1939), 12 July, p. 5, viewed 6 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article123411893

72 Cobby, pp.81-82.

73 Cobby, pp.85-86.

74 Weingarth, Gerald 1999, ‘AFC leave UK’, ‘14 – ’18 Journal, Australian Society of World War One Aero Historians.

75 Cobby, p.94.

76 Cobby, p.94.

77 1919 ‘ANZAC DAY.’, The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 – 1957), 29 April, p. 5, viewed 10 October, 2013, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article1462192

78 Cobby, p.102.

79 Richards, p.50.

80 Weingarth, ‘AFC leave UK’.

81 Quoted in Coulthard-Clark, p.27.

82 Coulthard-Clark, p.28.