A Mosman boy of 15 who bluffed his way to fight at Gallipoli, was wounded and repatriated home only to re-enlist under his real name for the Western Front in 1917; a pioneering Australian aviator who saw the future of air travel decades before most, went broke several times doing it, and crashed in the Pacific just as formal recognition and a knighthood was to be his.

On arriving at the firing line grim sights confronted us. Dead & wounded lay in heaps behind the parapet and worn-out Australians crouched close under cover. The looks in their faces and on the faces of those lying on the ground greatly impressed me. Chaos and weird noises like thousands of iron foundries, deafening and dreadful, coupled with the roar of high explosives or coal-boxes as they ripped the earth out of the parapet, prevailed as we crept along seeking first of all the serious cases of wounded. Backwards & forwards we travelled between the firing line and the R.A.P. [Regimental Aid Post] with knuckles torn and bleeding due to the narrow passage ways. “Cold sweat”, not perspiration, dripped from our faces and our breath came only in gasps.

W.J.A. Allsop, diary entry on the Battle of Fromelles

The two Franks, one blind and the other paralysed, became a familiar sight in Mosman, indeed a sort of living war memorial. They had a motor bike and side car which Cluett, an engineer by training, had modified so that he could drive it while sitting in the side car, with Morris on the bike saddle.

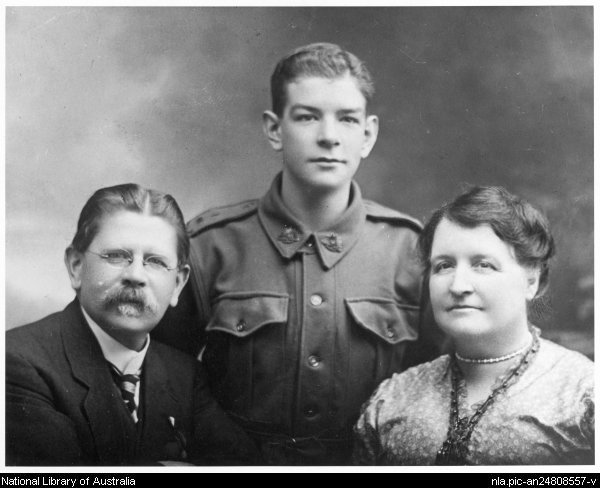

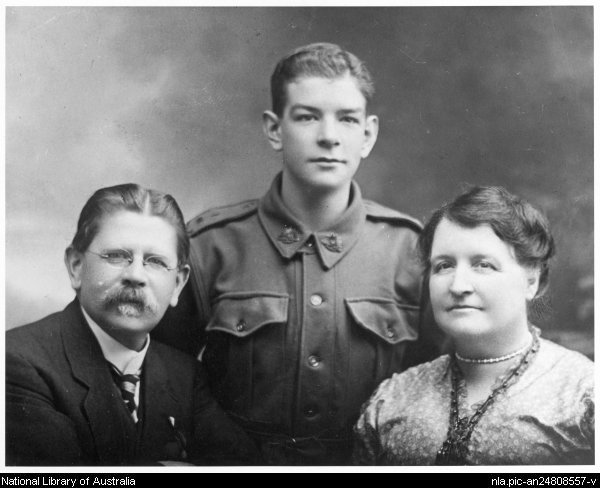

This photograph is just one of the thousands of photographs of Australian and other allied soldiers taken during World War I that have been discovered in France, in a find hailed as “wonderful and thrilling” by military historians.

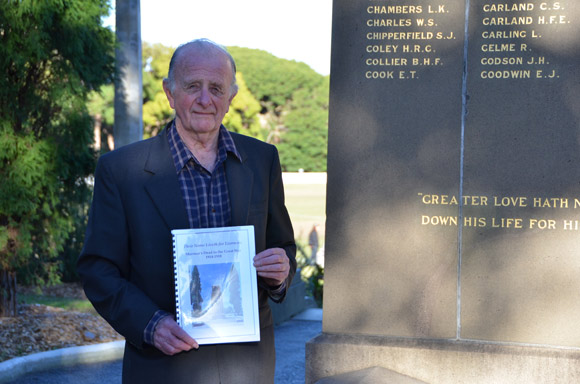

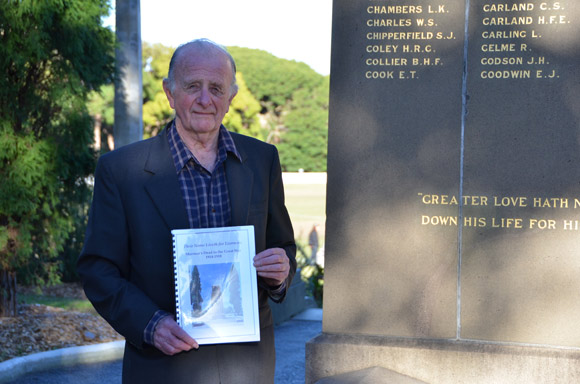

It was a pleasure to meet with author and historian George Franki on Friday. I am reading his book on Australia’s most decorated soldier Mad Harry published in 2003 but more recently he has produced a fine work remembering Mosman’s dead in the Great War.