Smith’s Weekly, 1 December 1923, p. 26

‘Most Expensive Airman of the A.I.F.’ said popular tabloid Smith’s Weekly in 1923.

Mosman pilot Eric Dibbs reckoned he’d crashed 13 aircraft in his time with the flying corps. If the tale is a little tall in the retelling, who can begrudge a man who made it back from the Western Front?

He wasn’t an ace but took his chances over the trenches — and won.

Our man Dibbs

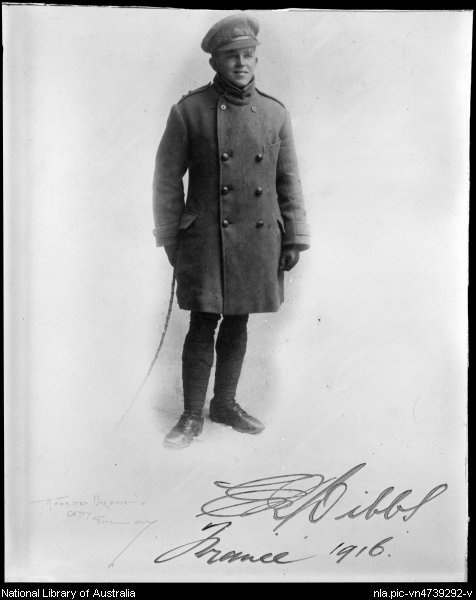

Lieutenant E R Dibbs, France 1916. Image: National Library of Australia

Eric Rupert Dibbs was born on a hot, late summer’s afternoon at his parents’ home “Boltibrook” in Lytton Street, North Sydney. The date was 9 March 1894. Eric was the first of five children to Sydney Reginald Dibbs (1867-1931), a senior clerk at Customs House, later Chief Inspector of Customs for New South Wales, and Jessie Emily Fletcher (1869-1937) of Maitland, NSW.

The family had a long association with Sydney’s northern harbour suburbs, living at Lavender Bay (“Sunnyside”, c.1894) then Mosman (“Woodlawn”, Cross Street, c.1916 and 29 Gordon Street, c.1918). Our man Dibbs would return to Cremorne and Mosman in the early 1920s.

Of his extended family, whose Sydney history dates to the arrival of master mariner Captain John Dibbs in 1821, we should highlight Eric’s great uncle, Sir Thomas Allwright Dibbs, general manager of the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney. In 1915, appalled at the carnage being wrought by the war, Sir Thomas Dibbs bequeathed to the government his estate “Graythwaite” as a convalescent hospital for sick and wounded soldiers.

Graythwaite c.1880. Photographer B. Goode. Image: SLNSW SPF/392

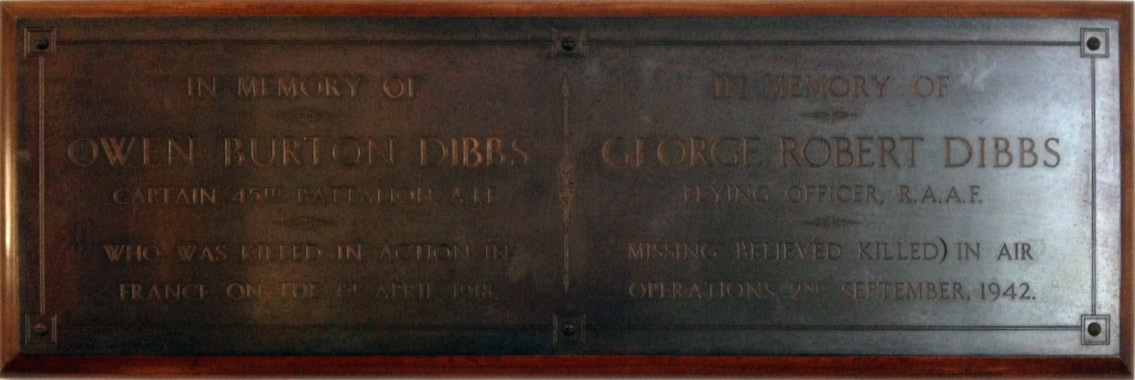

It was at this fine North Sydney home, in the late 1940s, that a memorial plaque was erected in the entrance hall at Eric’s initiative.

It remembered Sir Thomas’ grandson Captain Owen Dibbs, 45th Battalion AIF, killed in action at Dernancourt in 1918, and great-grandson Flying-Officer George Robert Dibbs RAAF, killed in action over El Alamein in 1942.

The plaque erected at Eric Dibbs’ initiative at “Graythwaite”.

The plaque sat alongside an earlier memorial to the first of Sir Thomas’ grandsons to fall — 2nd Lieutenant Thomas Graythwaite Dibbs, 7th Battalion York and Lancaster Regiment, British Army, was killed in action in Flanders in 1915.

The memorials are now housed in the Graythwaite Rehabilitation Centre in Ryde1.

For Eric the military was a life-long fascination.

Aged seven, he turned out in sailor suit at Martin Place for a march past of imperial troops that celebrated Australia’s Federation in 1901. Dibbs gave the Duke and Duchess of York ‘a smart naval salute.’

He recalls too the ‘fine sight’ of the New South Wales Imperial Bushmen riding down Macquarie Street to embark for the Boer War. In the procession, at the head of a detachment of the volunteer National Guard, was another of his great uncles, Sir George Dibbs.

His mother’s side of the family could lay claim to service in the Napoleonic Wars.

My dear mother was extremely proud of the Hamilton Smith family portraits of which five were then in her possession. Later they were distributed to various members of the family. I said to my mother “Why don’t you have portraits painted of Vern and I?” This idea did not appeal, my mother remarking that it was “alright” for Charles Hamilton Smith as he was a “real” soldier. Such is the effect of ‘early ancestor worship’. It carried more weight in my mother’s mind than the fact that her two elder sons had been well blooded in war.

As custodian of the Dibbs family story, Eric Dibbs was a prolific letter writer, note taker and record keeper. His papers and photographs are now archived at the State Library of NSW and National Library of Australia. He took great pride in his family history.

You can also encounter Dibbs in Australia’s official military records. He was briefly Recording Officer for No. 2 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps (AFC), and he compiled the nominal roll of officers and other ranks for No. 3 Squadron AFC. Frederic Morley Cutlack, author of the official history of the Australian Flying Corps, acknowledges some assistance from Dibbs in his preface2.

Thanks to a 1967 interview with the Australian Society of WWI Aero Historians, an oral history recorded with Fred Morton in 1976 and notes published by his granddaughter in 2013, much of Dibbs’ WWI story can be told in his own words3.

Stepping into khaki

In June 1914, employed as a clerk at the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney, Eric Dibbs was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 24th Infantry (East Sydney). The regiment formed part of Australia’s territorial militia, the Citizen Military Forces. From 1911, all boys had to register for cadet training, and Dibbs would have progressed from senior cadets to his local regiment.

War was then regarded as a dim possibility by the younger generation. Within a little over 6 weeks we were at war with Germany.

The East Asia Squadron of the Imperial German Navy was at large in the Pacific, so the militia was put on alert to man the city’s defences.

We were camped at Maroubra, mostly low scrub at that time and we had an Officers Mess in Dudley’s store, at Dudley’s Corner.

But no action was forthcoming for Dibbs or his regiment, and he was as yet too young for a commission in the Australian Imperial Force.

Though I volunteered for the AIF, I was not at first successful, as officers had to be at least 23 years old before they were eligible for overseas duty.

However, I passed through 2 officers’ schools in March and June, 1915, and functioned as adjutant and company commander (combined) at Warwick Farm, and later as company commander at Liverpool, in NSW, till my appointment to the 36th Battalion, AIF, on 2nd February, 1916.

The boyish-looking Lieutenant Dibbs, second-in-command of “C” Company, 36th Battalion, AIF, was 22 years of age, 5 foot 6 inches tall and 10 stone 1 pound (64 kg) in weight.

With his brother Vern4, now also in the 36th, Dibbs marched to war from an overnight billet in the poultry pavilion at Sydney Showground. The battalion embarked for England from Woolloomooloo on 13 May 1916.

My cabin was number 13 and it has always been my lucky number.

Sailing via Cape Town and Dakar, the requisitioned P & O liner Beltana reached England in June. From Devonport the men entrained for Amesbury, which they reached in the still hours before dawn.

[W]e marched through the sleeping village, past lovely old cottages with white doorsteps and shining doorknobs all under the overhanging greenery of beautiful English trees.

The 3rd Australian Division, to which the 36th Battalion belonged, had only rudimentary training in Australia. Lark Hill camp on Salisbury Plain, not far from Stonehenge, would ready them for the trenches.

First impressions were favourable. The camp covered about 10 square kilometres, housed some 40,000 inhabitants and came complete with streets, canteens, theatres, restaurants and shops. In time it would have its own trenches, listening posts and no man’s land, a Western Front in miniature. The intensive training, sometimes with live ammunition5, prepared the citizen soldiers for much worse to come.

Lieutenant Eric Dibbs in England, just before the 3rd Division embarked for the Western Front in 1916. On his right shoulder is the colour patch (white over green) of the 36th Battalion. Image: National Library of Australia

This fine Division, filled with a fervent desire to serve King and Empire, trained on the Plains for 5 months.

Then after a review by His Majesty the King, we left for France in November, 1916. I remember it was snowing. As the Division was pulling out, I was ordered to report at once to Divisional HQ to understudy my old friend Major J.H.F. Pain (later Colonel, DSO, MC) as a Staff Trainee.

Major John Pain6, a graduate of the Royal Military College, Duntroon, was one of five brothers7 from Cremorne Point who served with the 1st AIF. Pain was a capable and energetic staff officer who had distinguished himself in the field, commanding a company of the 2nd Battalion at Gallipoli, where he was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry in the Battle of Lone Pine. Wounded in that action, he was invalided to hospitals in Malta and England, before being appointed in October 1916 to Major General John Monash’s headquarters as General Staff Officer (Grade 3).

Dibbs was to be his understudy.

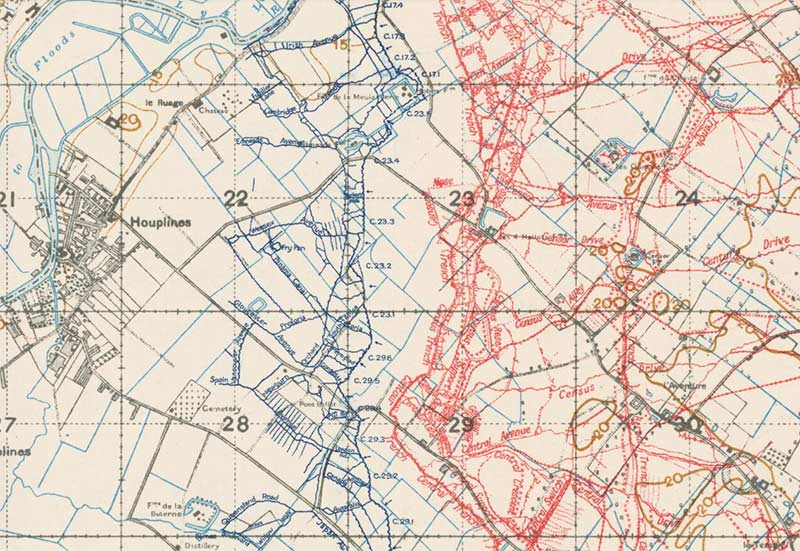

The two men traveled with headquarters staff to Steenwerck in French Flanders where Monash’s 3rd Division was assigned the Armentières section of the line.

I was sorry to be leaving the 36th, but naturally delighted to be at the nerve centre of the Division in contact with that fine soldier Major General Monash (later General Sir John Monash). It was a delight to work with him. He was as much in contact with the younger members of his staff as he was with the more senior officers.

They were sited not far from the front line that snaked north to Ypres and south-west to Fromelles. Here Dibbs learnt the art of the intelligence officer, putting together information from observation posts with aerial photographs, captured documents and prisoner statements.

Trench map 36.NW, October 1917, showing area east of Houplines. British trenches are in blue and German trenches in red. Image: National Library of Scotland

The Division had been given a ‘quiet’ sector but the Western Front exacted its toll regardless. In January 1917, Dibbs was alerted that his brother, manning frozen trenches in front of Houplines, had been badly wounded.

At 2pm on the 22nd January the enemy put down a heavy barrage on the 36th Battalion front. Vern was in the front line commanding a platoon of “D” Company. The 5.9 [inch] shell struck a gas cylinder and Vern and his platoon “copped the lot.” A number of Vern’s men died and the remainder were incapacitated.

I borrowed a Daimler from HQ and went over to the 9th Field Ambulance near Houplines. A large room was filled with coughing, spluttering dying Australians. Most of them had an ashen-greenish look and Vern was obviously in a bad way.

The battalion lost 11 killed, 4 missing and 36 wounded as the German army shelled – then raided – the Australian trenches. 2nd Lieutenant Vernon Dibbs was evacuated to England.

In April, the 3rd Division took over the Messines–Wytschaete Ridge from where, in early June 1917, they would take part in their first major engagement of the war, the Battle of Messines. But by then Dibbs had taken to the air.

After 5 months on Divisional HQ, I noticed in the office of GSO 3, a large pile of applications from members of the Division wishing to become observers in the Australian Flying Corps. I quickly rustled up a form, filled it out, and placed it on top of the pile. I then reported to the GSO 2, Colonel E H Reynolds (first commanding officer of No. 1 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps) and told him what I had done. His only reply was, “You cannot expect any preference through being on Divisional HQ, and will have to take your chances with the others.” Later, he told me I had all the necessary qualifications, and that I would be duly transferred to the AFC as desired. General Monash was most kind when I bid him farewell. “You have a future here, Dibbs, but if I were a young man I would do precisely the same thing.”

Seven officers and twenty-five other ranks were sent to England to be trained as observers for the Australian Flying Corps.

Dibbs: the army’s eye in the sky

An observer’s brevet — a single wing with an O at the root. Image: AWM REL37431

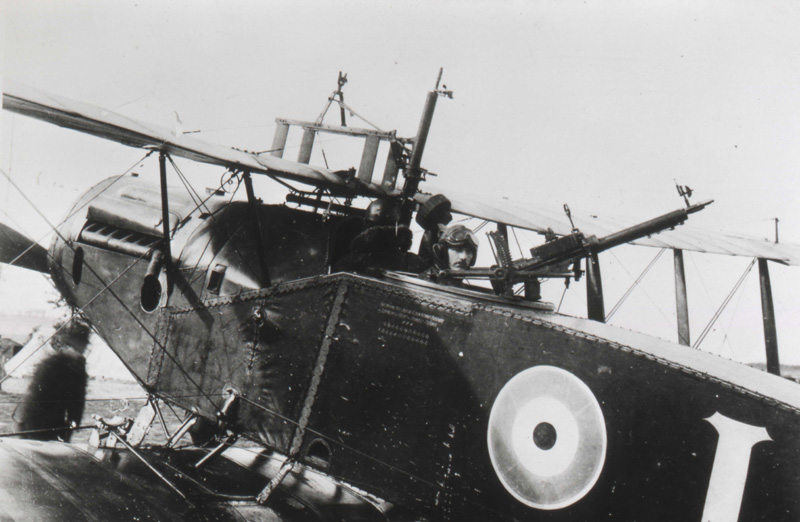

In the first days of the war, before machine guns were timed to fire safely through the propeller and pilots became aces, the observer was senior to the officer who chauffeured him over the lines.

The observer’s job was to reconnoiter and photograph enemy positions invisible to men pinned down in trenches. By correcting the fall of shot, the observer could direct the artillery’s guns onto them.

The observer was gunner too, the open cockpit mounting one or more machine guns for attack or defence, although there were not always seatbelts.

They said seatbelts would make us lazy.

Dibbs tells of one close call when serving with the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in France. The pilot was John Barnett, a tall, fair Englishman nicknamed ‘Pull-through’8.

During a fight over Cambrai, we got separated from the main formation, and in his anxiety to get a Hun aircraft, [Barnett] pushed the stick so far forward that the aircraft wound up on its back, with the entire contents of the observer’s office hurtling to earth – all except me. By dint of grasping the cross-bracing wires, I was able to save myself from a spectacular and messy end.

But that was in Dibb’s future. First he had to go to school.

Eric Dibbs in forage cap and 1912 pattern ‘maternity’ jacket with rising sun collar badges. This style of cap and tunic was worn by aircrew and ground crew. The photograph was probably taken in England when Dibbs was training as an observer. Image: National Library of Australia

Training airmen in the early days of aviation was as rudimentary as the aircraft in which they were to fly. The First World War came just 11 years after the Wright brothers’ first flight.

In April 1917, Dibbs attended No. 1 School of Military Aeronautics at Reading, west of London. Observer cadets received a month of instruction on the ground, with lectures and workshops on navigation, wireless telegraphy and aerial photography. One room was kitted out with a gallery from which cadets could practice artillery spotting on the relief model below.

Dibbs then spent a week or so on Lewis and Vickers machine guns at the School of Aerial Gunnery at the south coast town of Hythe. There, on 25 May 1917, he was witness to the first air raid against England by German aircraft.

I’d just had a shower at the Imperial Palace Hotel on the waterfront at Hythe. I heard bombs dropping all around. I wrapped the towel around me, ran into the hall and looked out the window. Right up high were about a dozen or more German aircraft.

21 heavy bombers attacked Folkestone that day. The twin-engined Gotha G.IV was a formidable biplane with a crew of three, a wingspan of 24 metres and a bomb load of 500 kg. The bombers’ target was London but cloudy skies over the capital saw them turn back to attack the Channel port instead. 95 were killed and 195 injured. A few weeks later, the Gothas reached London causing 162 deaths and 432 injuries, the deadliest air raid of the war.

Dibbs had another experience of ‘the first Blitz’ although the date is not known. He was staying in London at the Ivanhoe Hotel, ‘a favourite spot for quiet minded Australians’ not far from the British Museum, when he slept through a Zeppelin raid.

One morning I heard the sounds of a bugle and on inquiring was informed that this was an “all clear” signal, sounded by a Boy Scout in the course of duty… a Zeppelin had dropped a bomb in the yard of the hotel during the night and it had not “gone off”.

Having passed his gunnery tests at Hythe, Dibbs qualified on 2 June 1917 as an observer in the flying corps.

Lieutenant Eric Dibbs in AFC officers service dress tunic with observer’s brevet (single wing with letter O). This photograph has been reversed. The observer’s wing was worn above the left chest pocket and the forage cap high on the left side of the head. The photograph was taken between June 1917 and May 1918 but most likely soon after Dibbs qualified as an observer. Image: National Library of Australia

Before returning to France he met with his brother at the Australian Officers’ Club in London. Vern had convalesced at Cobham Hall, home of the Earl and Countess of Darnley, then spent a week with the Earl and Countess of Strathmore, whose daughter was the future Queen Mother.

All he seemed to want to do was talk about the wonderful girl he had met, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon.

Dibbs sailed for the Western Front on 10 June 1917.

A month after leaving France, I was back on the quayside at Boulogne, and there I discovered that I was posted to the famous No. 11 Squadron RFC, among whose ranks had flown such outstanding members as Albert Ball, and Lieutenant Insall, both VC winners.

11 Squadron RFC

Dibbs was joining a distinguished unit that could lay claim to being the first fighting squadron on the Western Front. 11 Squadron had deployed to France in July 1915 with the Vickers ‘Gunbus’, the first aircraft purpose-built for combat in the air.

When Dibbs joined the squadron at La Bellevue they had just been equipped with the Bristol F.2B, a two-seater fighter reconnaissance machine popularly known as the Bristol Fighter or Biff.

Replica Bristol F.2B built by The Vintage Aviator Ltd, New Zealand.

For its weight and size, the Bristol Fighter was fast and manoeuvrable. In combat, the pilot had a forward-firing Vickers gun while the observer commanded an excellent field of fire with swiveling single or twin Lewis guns.

In good weather we did 2 patrols over the lines each day (either DOP or COP patrols – Distant Offensive Patrol or Close Offensive Patrol). There was also an officially unknown-of VIP (Very Inoffensive Patrol) allegedly occurring after a very heavy night in the Mess. Then, from time to time, we went on long-distance photographic recce flights, or escorted the same type of job.

Dibbs’ early days with the squadron were limited by tonsillitis that resulted in a week’s stay at the 3rd Canadian Stationary Hospital in the citadel at Doullens. He enjoyed the company he found there and entertained his friends by gargling the national anthem.

In the air he was paired with Captain Ronald Mauduit, a partnership Dibbs described as ‘active and exciting.’

He was a splendid fighter pilot, and when we were in action, we were really in it. I used to enjoy the early morning patrols. An orderly would come round in the dark, grab me by the shoulder, and inform me sotto voce that the patrol would leave in 20 minutes. There was then a rush to climb into flying gear, grab maps, and tear across the field to the mess for a quick cup of lukewarm coffee and a greasy egg. Then out to the aerodrome where the Bristols were ready running to warm them up. We usually went out in threes, or sometimes fives, climbed towards the lines, and arrived over Hunland at about 10,000 or 12,000 feet.

As soon as we crossed the lines shell bursts from German batteries would begin bursting round us. Whenever they suddenly stopped, we looked for enemy aircraft, and kept our eyes well open. Sooner or later, we would spot them – tiny specks like so many midges in the distance. As we closed, we climbed for height and did our best to get the sun behind us. Of course, they were trying to do exactly the same thing.

The Bristol Fighter could dive faster than its adversaries, a singular experience for the observer.

When the leader fired a red Verey light [flare], we would put our noses down and dive headlong into the enemy formation. This was sometimes alarming for the observers loose in their cockpits. Only the pilot was strapped in. Those were unforgettable moments – as the pilot dived, the observer was flung on his back with his feet pointing up to the blue sky. He was reassured by the sound of the front gun firing and the smell of the cordite fumes. When the front gun stopped firing, you were in suspense, wondering whether the pilot had been killed, till either he fired again or the machine lurched out of its dive. This went on till the E. A. [Enemy Aircraft] were either destroyed or driven away. Each time the pilot pulled out of a dive, the observer had to clamber to his feet against the centrifugal force, swing both Lewis guns in the direction of the nearest E. A. and let fly. Masses of tracer and hundreds of unseen bullets would be flying in all directions and the opposing aircraft would be wildly dog-fighting in a mad, whirling mass.

One fight is very like another at this distance of time, and I find it difficult to separate them. I can assure you, however, that we were never, never bored. I must admit that I sometimes dozed off in the thin atmosphere on a sunny day when we were not in contact with the enemy. Mauduit would often give me a hard crack on the head to make sure that I was awake…

Bristol Fighter of 22 Squadron RAF in July 1918. Image: Monmouth Museum M1996

As an observer I often wore a lambs wool coat with the wool on the outside. Mauduit loved to refer to me as “his little Canterbury – a lamb led to the slaughter”.

Two aerial victories were awarded to Mauduit9 in July 1917 with Dibbs in the observer’s seat. On 12 July at 8.15pm, an Albatros D.V was sent out of control at Pevles. On 20 July at 6.45pm, another Albatros D.V was sent out of control at Novelles.

They are the only official aerial victories recorded against Dibbs’ name.

Albatros D.V single-seat scout with 200 horsepower Mercedes engine. Image: IWM Q 63852

With Mauduit, Dibbs also recorded the first in his unofficial tally of crashes. It happened on return from a patrol in Bristol Fighter A7145 on 7 July.

After a couple of exciting fights, [Mauduit] glided in to land [at La Bellevue] and was suddenly aware of a high row of poplars. He pushed the throttle open to clear them, and the engine choked and died. He then turned vertically to the right, and found himself facing another row of trees. We just kept on turning and losing height till at last the wing tip struck the ground; there was an appalling crash and I was hurled out 30 feet from my cockpit, landing in a wheat field – fortunately very soft.

I picked myself up and struggled back towards Mauduit, whose legs were sticking out from under the machine which, incidentally, was a complete wreck. After tugging at his feet, I realised that he was still strapped in, though the force of the crash had pushed his seat from his own cockpit into the observer’s ‘office’. Mauduit cursed as he realised that the escaping petrol could easily set the wreck afire. However, I got him clear. Just then a group of officers and ORs [Other Ranks] turned up with stretchers and a Ford ambulance. When the pair of us walked away from the wreck to meet them, they were astonished for it indeed looked that it would not have been possible for us to survive that landing.

At the Canadian hospital Dibbs saw his friends again.

During the afternoon’s proceedings, I had sustained a slight scratch on the neck, and now, in view of the crash, it was deemed advisable for me to go down and visit the 3rd Canadian CCS at Doullens for an anti-tetanus injection. This was quite a pleasant interlude.

Second Lieutenant Richard Raymond-Barker. Image: IWM Q 72832

He was soon in the air again, this time with Richard Raymond-Barker, a British ace who would be Manfred von Richthofen’s penultimate victim in April 1918.

Capt. (later Major) Richard Raymond-Barker had the misfortune to lose two observers in quick succession. I remember there were real tears in his eyes when I offered to fly as his observer in Mauduit’s absence. He was a splendid pilot.

I have the most vivid recollection of an occasion when GHQ required urgently, photographs of 13 enemy airfields on No.11’s front. Dick Raymond-Barker led a formation of about a dozen Bristols and I functioned as his observer for the trip, and took the necessary photographs. In modern parlance it was a ‘piece of cake’. Being in such unusual strength, it was a pleasure cruise, and we didn’t see a single E.A. on the whole trip, though we went 20 miles inside their lines in brilliant sunshine. The result was that we were able to get eleven perfect photos, and GHQ were delighted… so much so that Raymond-Barker was at once awarded the Military Cross10.

Dibbs spent just under 3 months with 11 Squadron. They were, he said, his most exciting time at the front.

No. 11 was essentially an Empire unit, and we had in it 3 Australians, a number of Canadians, 2 South Africans, a Newfoundlander, as well as representatives of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. The Australians were Captain Geoffrey Hooper and myself, and Captain Edye Manning.

Among the Canadians was Andrew Edward McKeever, already a leading light in the squadron, later to become with 31 victories the highest-scoring Bristol Fighter ace.

The Biff Boys by Robert Taylor. Flying a Bristol F.2b fighter, Lt. Andrew McKeever and his gunner Lt. Powell of 11 Squadron RFC engage German Albatros D.V fighters over the Western Front near Cambrai, 30 November 1917.

Dibbs wrote a short story based on his experiences with 11 Squadron. The Murrumbidgee Irrigator published ‘A Day with the Flying Corps’ in 193011. McKeever (‘Hawkeye’) is mentioned, as are two pilots (‘Smith’ and ‘Jones’) that do not return.

In Dibbs’ time with the squadron they suffered 28 casualties12 — 17 pilots and observers killed or died of wounds, 6 taken prisoner and 5 wounded.

We lived literally from hour to hour.

As his time with 11 Squadron neared its end, Dibbs’ luck was again to the fore.

I was without a pilot pending my transfer to the AFC, which had just arrived in France, and I arranged to fly with Lt. Miall-Smith. However, on the morning of this intended flight, I was already on my way to No.3 Sqn, AFC, and learned later that Miall-Smith and the observer he took in my stead had gone down in flames13.

Such are the fortunes of war.

When Dibbs was on leave in London in August 1917, he had met Major David Valentine Jardine Blake, Commanding Officer of 3 Squadron AFC, and told him that the 7 Australian officers trained as observers and meant for the Australian Flying Corps were serving in British units14. Soon after Dibbs was recalled to the AFC.

3 Squadron AFC

3 Squadron was the first Australian flying unit on the Western Front. It reached its aerodrome at Savy-Berlette, west of Arras, on 10 September 1917.

Dibbs and his compatriots from observer school Sydney Moir15 and Vincent Barbat16 joined the squadron a week later. Dibbs was assigned “A” Flight.

3 Squadron AFC was an army co-operation squadron, its tasks reconnaissance and artillery spotting.

Their service machine was the Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.8, a somewhat ungainly-looking beast with twin exhausts atop a prominent snout. In popular parlance the R.E.8 took the name of an English comedian, Harry Tate. Its stability became legend when a single bullet killed both its pilot and observer and the aeroplane flew itself until the petrol ran out. The machine landed unaided without injuring the bodies of the unfortunate James Sandy and Henry Hughes. But the R.E.8 was also somewhat slow and, with a difference of just 20 to 30 miles per hour between cruising and stall speed, required an attentive and experienced pilot.

Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.8. Image: IWM Q 68147

The R.E.8 was a step down from Bristol Fighters, said Dibbs.

One day we landed at No. 11’s aerodrome, and several of my friends came out to the R.E.8 to greet us. They made some most disparaging remarks regarding the R.E.8 and referred to its engine as a chaff-cutter.

On the other hand it was nice to have caught up with other members of the AFC. [The Australian squadron] seemed glad to have us, as we were the only members to have seen active service.

The squadron record book shows Dibbs on a number of practice flights with different pilots during his first month at Savy-Berlette.

Pilots and observers were paired off in England before leaving for France, and for a while Moir, Barbat and I were employed on odd jobs such as putting together aerial photographs to form a mosaic of the front lines. As these had in many cases been taken at varying altitudes, it really was hardly possible to do a good job. However, it was obviously the C.O.’s intention to keep us employed till he found us pilots.

Dibbs’ first artillery patrol came on the morning of 24 October 1917 with pilot Alan Paterson17. At 5,000 feet over the German-held city of Lens, they ran into a formation of five enemy scouts. Three in succession dived on the Australian machine. Dibbs kept the attackers at bay, firing 30 rounds.

This incident may be the source of Dibbs’ story about acting as instructor to ‘inexperienced pilots’ in the squadron.

One very game young man, without the slightest idea of what was expected of him, took me one day right over the lines, a thing he was certainly not supposed to do at the time, and we were soon involved with several Albatros scouts. The enemy pilots must have got quite a shock to see a lone R.E.8 so far into their territory, and probably suspected a trap. In any case, they attacked with gusto, and I was kept very busy shouting instructions to the pilot and operating the rear Lewis gun till we once more made our own lines, where the German pilots turned away and headed for home.

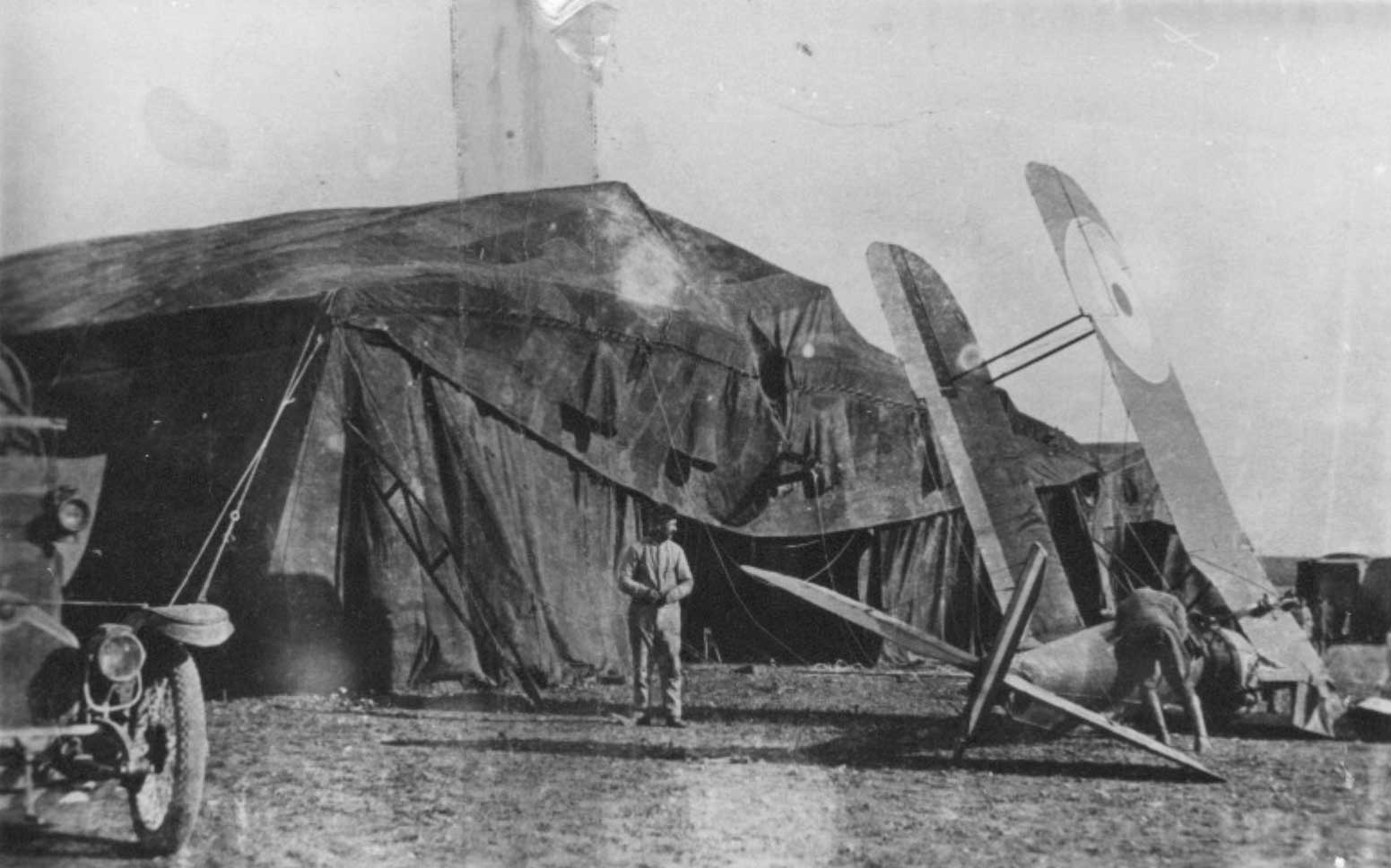

An R.E.8 of No. 3 Squadron AFC preparing to set out on a night bombing operation from Savy, 22 October 1917. The pilot is Lieutenant Stanley George Brearley, the observer Lieutenant Robert Harold Taylor. The fuselage sports the squadron’s white circle insignia. Note also the pilot’s Vickers machine gun, fixed port-side, synchronised to avoid hitting the rotating propeller blades. Image: IWM E(AUS) 1178

Dibbs’ next patrol was on 30 October with Reg Francis18, a pilot who would distinguish himself with the squadron. But this particular morning, gusty with poor visibility, resulted only in an unsuccessful shoot and a crash on landing. It must not have been serious as neither Dibbs nor Francis’ papers record an injury.

Dibbs was up the following day with Ernest Jones19, another pilot at the start of a distinguished career, and Dibb’s partner for the rest of his time with No. 3 Squadron.

Ernie was a good pilot, short and slight, and with ginger hair. He was as game as Ned Kelly.

On a fine day with only intermittent clouds, the pair took off at 11.25am to patrol the line between Arras and Lens. Three enemy aircraft were spotted over Liévin and Vimy but not engaged.

Replica Albatros D.Va built by The Vintage Aviator Ltd, New Zealand.

Later, at 12.50pm between Méricourt and Neuville-Saint-Vaast, they saw four Albatros D.Va scouts attack their flight commander, Captain William Anderson20, who was busy ranging the 6-inch howitzers of No. 108 Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery.

Anderson adroitly manoeuvred his machine for the observer whose guns kept the colourfully marked enemy formation at bay.

Jones and Dibbs leapt into the fray.

As the Huns swooped down in succession onto Anderson, we moved closer in support and were soon getting the concentrated hate of all [the] fight.

Dibbs fired two drums, and the combined action of the R.E.8s was enough to see off the Albatros formation. A phlegmatic Anderson recalled his battery and completed the shoot.

We expended a lot of ammunition, but finally made it back to the line, where the Huns once again peeled off and went their own way.

I shouted across to Ernie, “Are you alright?” He nodded and headed for an aerodrome near the line21. When we landed, he asked, “Where are you hit?” We both laughed at the misunderstanding. The machine was full of holes, and we later found that two main spars had suffered. We were lucky to make that flight back to Savy without mishap.

It was Jones’ first trip over the lines in France. Their machine had been hit 16 times.

Replica R.E.8 built by The Vintage Aviator Ltd, New Zealand.

On 8 November, the pair were part of a successful bombing mission in support of a large raid by the British 31st Division near Oppy. Three formations of the squadron crossed the lines at 12 noon. “B” and “C” Flights bombed the village of Neuvireuil while “A” Flight, led by Anderson and including Jones and Dibbs, dropped 40 pound phosphorus bombs to lay a smokescreen for the infantry.

That raid completed 3 Squadron’s induction to the Western Front. The next day they received orders to move to Bailleul and take over as corps squadron for I ANZAC. It was the first time an Australian army corps had with it an Australian squadron.

They arrived soon after the capture of Passchendaele.

Bailleul was an old well-provisioned RFC aerodrome. We took over the mess and became the proprietors of a most astonishing line of liqueurs, which provided quite an education for most. At Bailleul, Jones and I shared a hut labelled ‘Enid’s Shrine’, why I will never know. The huts were in a quadrangle and had all been named by their previous RFC occupants.

Bad weather prevented much flying but five sorties by Jones and Dibbs are recorded in November. This report in the squadron war diary is typical of these patrols.

23 November 1917, E J Jones and E R Dibbs in R.E.8 A3817, 2.25pm to 4.10pm. Artillery observation with No. 425 Siege Battery of 6-inch howitzers. Successful ranging shoot by pilot on enemy battery PY 54. Called up the battery at 2.35pm. First signal to fire sent at 2.40pm. Observed 16 rounds obtaining one hit 300 yards out, three 200 yards out, six 100 yards out, six 50 yards out. Our battery put out a V ground-strip signifying ranging considered complete at 3.45pm. Observed during battery fire for effect 4 hits slightly out. Signal ‘coming in’ sent at 4.05pm. Visibility bad. Damage done to target uncertain. [Also noted in the report are the location of a fire burning at 3.10pm and two flashes from enemy guns seen at 4.10pm.]

After several days at an artillery liaison course at the end of November, Dibbs heard of another move.

Barbat and I received instructions to proceed to England for pilot training. This suited us to the ground, as we were all dead keen to learn to fly. The C.O. [Major Blake] marked my transfer papers “Recommended for training on fighters or scouts”. This was just what I wanted and is how it finally turned out … We had survived 6 months as observers in France, and were going on to the pilots’ course with great joy.

Dibbs gets his wings, and crumples a few more

Dibbs wearing flying coat, helmet, goggles and gloves. The photo is dated 27 January 1918 on the reverse. Image: Joanne Howard née Dibbs

After a month’s leave, during which he toured the ruins of the Easter Rising in Dublin, Dibbs reported to No 1 School of Military Aeronautics, Reading, on 4 January 1918, before being passed out to the AFC Training Depot at Wendover, Buckinghamshire, on 26 February.

Practical flight training began in March 1918 at Minchinhampton, Gloucestershire, with 6 (Training) Squadron AFC.

Instructors took us up in Avro 504s, of which there were three types – powered by 80 hp Gnome, 100 hp Monosoupape, or by 110 hp Le Rhone. They were all rotaries. The Gnome was not powerful enough, the Le Rhone was very good, but the Monosoupape sometimes caught fire in the air. We were told not to worry if this happened, as the fire should blow itself out. In fact, this happened to me on one occasion, and sure enough the fire went out after only a few seconds.

After 6 or 7 hours of dual, I taxied out one day with my instructor, in a Le Rhone engined Avro. He jumped out quite unexpectedly and just said, “Right, Dibbs, off you go.” So I pushed the throttle forward and went round in a circle on the ground. Looking very alarmed, the instructor rushed up to see if everything was alright. Then I tried again, this time heading the machine up into the wind. I took off and suddenly realised that I was at 2,000 feet, quite alone and completely dependent upon my own ability to land this machine unaided. However, after being up there for a few moments, I found I was able to control it without difficulty, so I circled the field twice, then came down and made a good landing. This got me a pat on the back from the instructor.

Australian Avro 504K (E3785) of No. 6 (Training) Squadron, 1918. Image: AWM A04627

It was an unwritten law in No. 6 that on your second solo you had to stunt. I took off in an Avro, climbed to 3,000 ft, and got into a position where everybody could see me. I didn’t know the Wingco [Wing Commander] was there on the tarmac also. “I’ll loop,” I thought, and pulled the nose up in the start of a loop, coming out with something like an Immelmann turn, and finishing up with a spin which must have looked spectacular from the ground. When I landed, Colonel [Oswald] Watt came over and slapped me on the back and said, “Good show Dibbs. Excellent.” Of course, it wasn’t what I had intended, but must have been very impressive.

A similar thing happened when Major Murray-Jones22 was instructing me and we were practicing forced landings with the engine switched off. He was in the front seat and I was pupil in the rear. He switched off the engine and pointed to a field below. I aimed at the field which I thought he had indicated, but missed it and landed perfectly in the next one. “Splendid,” he said. So once again I had struck it lucky.

Australian Avro 504K (H1925) of No. 5 (Training) Squadron, March 1919. Image: AWM D00418

Flight training could be as dangerous as flying in combat, whether the pilot was a rookie or a veteran. Dibb’s first instructor at 6 (Training) Squadron was 2nd Lieutenant Eric Grant23. He was killed stunting too near the ground soon after Dibbs arrived.

Our man continued to lead a charmed life.

I took off one day in an Avro (Gnome) on a training flight and something went wrong with the H.T. [high tension] lead. I landed in a 40 acre paddock and fixed it just as an old shepherd came up. He had been minding his sheep in the paddock. You couldn’t throttle the rotaries back, but had to buzz them with the switch, so I told the old fellow to stand and mind the switch while I swung the prop. Very rash, indeed, as I found out. For when the engine caught, the old man got the wind up and simply bolted. I ducked under the wing and made a leap for the switch, but was knocked over by the tailplane, and had to sit there and watch the Avro tearing across the field empty. It was just about to take off when the landing skid sticking out in front skewered an old ewe. The tail came over the machine broke its back. It was a horrible mess. Up ran the shepherd with, “You bin kill sheep master.” “Damn your sheep,” is all I could reply in anger, “I’ve busted my aeroplane.”

He disappeared, and came back with the proprietor, a typical English squire complete with hard hitter hat and briar stick. He was red in the face and furious about the loss of the animal, and not the least sympathetic about my ruined Avro. However, I managed to assure him that full compensation would be paid, and he went away pacified. Then who should arrive but his lovely daughter with a picnic hamper and bottle of whisky. So we sat down there and then and had a picnic while a little girl ran off to the aerodrome about 2 miles off to let them know what had happened. We sat a bit to windward of the sheep while we waited, and in due course Captain E J K McCloughry (brother of Major W.A. McClaughry, commanding No. 4 Squadron) arrived in his machine.

He was very sympathetic till he saw the girl, and then was very unsympathetic indeed.

Avro 504 (D6338) with 6 (Training) Squadron, 1918, upside down in a field. Not Dibbs’ doing. The photo affords a good view of the Avro’s landing skid with which Dibbs skewered the ewe. Image: AWM P08374.003

Dibbs also wrote off an S.E.5a (Scout Experimental 5), a modern fighter aircraft that was strong and robust. For safety, Dibbs rated it highly.

[O]ne day a most extraordinary thing happened. Just as I was about to lift off, the entire machine somersaulted. I was doing about 90 mph at the time, and to this day I have no idea what happened. Perhaps it was a failure of some of the control wires. Anyhow, it just turned over and over, finally coming to rest right side up with the wings all screwed up and the engine screwed out. There I was, sitting up in the midst of the remains with the wings sticking up either side, and completely unscathed.

Unfortunately, I had been in a number of crashes as an observer, and now that I’d had some of my own as well, it made quite an imposing total, which I did not relish altogether.

As well as the Avro and S.E.5a, Dibbs flew the Sopwith Pup in training.

They were light machines and simply delightful to fly. They were terrifically sensitive on the controls, and if for instance you wanted to loop, all you had to do was pull back on the stick, and you were over before you realised that you had started.

He says there was some idea that he might make a good instructor.

I wasn’t very keen, and one day when taking a Pup off, somehow dropped one wing and had a minor crash. It was nothing much and could be quickly patched in the hangar. I got out, saluted Major Cadogan-Cowper, who happened to be watching, and said, “I don’t think I’ll make a very good instructor, Sir. I think I’d better go back to France.” “Yes, I think so too,” he replied.

Dibbs was appointed Flying Officer on 2 May 1918. He had logged about 36 hours solo.

Just ‘finishing school’ remained — a fortnight in Scotland at No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting and Gunnery, Turnberry, where pilots practiced firing in the air and learnt the latest air combat tactics. It gave them, said Dibbs, a fighting chance when they were sent to the forward areas.

Ferry pilot: Dibbs does it again

In France, Dibbs was posted to No. 1 Aeroplane Supply Depot at Marquise, south-west of Calais. Here, newly arrived pilots not yet assigned a unit delivered new and replacement aircraft to fighting squadrons.

Dibbs recalls ferrying S.E.5s to Canadian ace Billy Bishop and seeing the Channel from the bomb bay of a Handley Page.

Two Handley Page O/400 heavy bombers on the RNAS Aerodrome, near Dunkirk, 20 April 1918. Image: IWM Q 12033

One day [James] Ross24 and I went over to England in a Handley Page with a lot of other pilots from Marquise, to bring back aircraft from England, as nearly all the England-based pilots were down with influenza. We were sat in where the bomb racks were usually fitted. Ross and I got in early and chose what looked like good seats, opposite two Canadians. Across the Channel, the Canadians kept opening a trap door at our feet and looking down. We were at about 8,000 feet. The door opened up towards them, meaning that Ross and I were sitting with our feet on the lip of the aperture, looking down at the sea 8,000 feet below. At long last we landed at Lympne aerodrome.

Dibbs saw out his ferrying days with a signature crash.

On one occasion I delivered an S.E. to Serny; it was a misty day and I was just recovering from a flu attack. After flying for some time looking for the place, I spied a triangular field below, which looked inviting, if a little small. I spiralled down and noticed a flock of sheep near the top of the triangle. There were hangars and offices across the base, and another hangar along the right hand side. It looked less inviting as I got nearer and of course the sheep were an extra hazard. I came in low over the row of offices and either I was still suffering effects of the flu, or had a momentary aberration, for suddenly something loomed up on my right wing and I flew slap-bang into the top of the hangar. The main beam of the hangar cracked with a sound like thunder, and the men working inside on motor transport thought the end of their world had come.

The S.E. spun round, and finished up in a swirl of dust, facing the wrong way and rather badly smashed. As I stepped out of the wreckage, a big Australian Sergeant Major came over to look into the cockpit. “Strewth,” he swore, “somebody beat me to the watch!” (In those days we carried an 8-day clock on the dashboard. They were very valuable, so ferry flights meant that they were carried in our pockets.) As the dust settled a little, who should come round the corner but Major Murray-Jones, who had been instructor to me in England. I saluted him and remarked, “Done it again, Sir”, but he just said, “Don’t be a damn fool, Dibbs”, and invited me into the mess for a drink.

I went over with him, and found all the pilots in the mess, whence he had sent them so they would not see the mangled remains (of me) in the wreck.

Dibbs’ crashed S.E.5a (B8520) at Reclinghem, 5 July 1918. Image: Joanne Howard née Dibbs

Sequel to this incident was that I was posted to No. 2 Squadron a fortnight after my rather unceremonious arrival.

2 Squadron AFC

With 4 AFC and 46 RAF (Sopwith Camels) and 103 RAF (DH-9 bombers), 2 Squadron AFC made up 80th Wing RAF supporting the Fifth Army in the north.

Dibbs joined the squadron at their aerodrome at Reclinghem on 18 July 1918 and was assigned to “A” Flight.

No. 2 Squadron’s service machine was the S.E.5a. This single-seat biplane was faster than any German type and outperformed the Sopwith Camel at altitude.

The S.E.5s were splendid machines with a top recorded level speed of 134 mph. But you could do 250 in a dive without any fear, as they had a very high safety factor.

I enjoyed flying them very much.

A flight of Vintage Aviator replica S.E.5a scouts over New Zealand.

Most scout pilots were short of stature, and I was shorter than most. I was unable in fact to get my legs right down into the rudder bar stirrups. Then somebody suggested I turn the stirrups upside down, and fly with the rudder bar inverted. This was done and for the rest of the war I flew with the rudder bar like that, and found it very pleasant. It also gave me good control over the machine.

Some of the other pilots got a laugh out of the arrangement, but I think I had the last laugh. On cold days when nearly all the others were frostbitten, I was afforded some protection by being able to snuggle well down into the cockpit. The saying was in No. 2 that if you saw an S.E. flying along on its own, that was Dibbs. I also had the tapered headrest removed from my machine, which made it look a little different from the others – it certainly afforded me a better all round view.

Dibbs pictured in an S.E.5a shortly after the Armistice, November 1918. The aircraft lacks the distinctive fairing behind the pilot’s head, suggesting it is one of Dibbs’ regular mounts. Image: AWM P00355.029

When Dibbs arrived at Reclinghem, the squadron had between 15 and 18 aircraft serviceable on any given day, a roster of between 17 and 20 pilots available to fly, about 30 officers in total and 170-odd Other Ranks.

We shared Rechlinghem aerodrome with No. 4 Sqn AFC, commanded by Major W.A. McCloughry. No. 4 saw a lot more air fighting than we did. They flew Camels and usually did their patrols at round 10,000 feet. We flew as a rule at 18,000 to 19,000 feet. I remember on one poignant occasion five of their Camels set out on a patrol, and only one lone Camel came back.

The German spring offensives of 1918 had been weathered and the allied forces were gaining the ascendancy. No. 2 Squadron AFC had distinguished itself in the desperate fighting between March and June and notable figures when Dibbs arrived were Eric Cummings, Roby Manuel, Adrian ‘King’ Cole, Roy Phillipps and Frank Alberry, the one-legged ace.

Officers of 2 Squadron AFC, Savy, 25 March 1918. Eric Cummings is in the back row, second from left. Roby Manuel is in the middle row, far right. In the front row, Roy Phillips is third from right. Image: AWM E01883

Dibbs was eased into squadron life with three days of training with fellow recruits James Ross and George Holroyde25.

When I joined No. 2, I had no combat experience, nor any training in formation flying either. This rather worried my flight commander, Edgar Davies. The first time out on patrol, we got up to about 15,000 feet and flew through a huge cloud bank. When we came out the other side, I was at least a mile to the right of the others, who had all stayed together. It was quite obvious that something would have to be done about it so the next day Edgar Davies took me up with him, with the single instruction “to stick as close as possible.” It was a terrific invitation and he was literally taking his life in his hands. But I did as he told me, and by that afternoon I had the hang of it and was able to fly in formation with the best of them. Believe you me, it is no fun formation flying through the clouds, and not being able to see a thing in front of you. You had to be all the time on the alert to avoid a collision.

The squadron record book doesn’t note this flight with Davies but does record Dibbs’ first patrol – at dawn on 22 July 1918.

In what was to become a familiar pattern, an enemy two-seater was seen but not engaged. Bad weather and a German air force husbanding its strength made enemy aircraft conspicuous by their absence. Dibbs flew another 3 patrols in his first month but saw only a couple of enemy aircraft, too distant to bring to combat.

But the quiet period had some incident.

Two S.E.5s from No. 2 Squadron and a Camel (4 Sqn AFC?) at the 4th Australian Divisional Race Meeting held near Allonville on 22 July 1918. The SE5 on the left is E5965 flown on this day by Lieutenant George Cox. Image: AWM E02835.

At the end of July 1918, 16 machines flew south to Allonville, near Amiens, for a race meeting where bets were made, perhaps for the first time, from the air27. Dibbs however fetched up short with a forced landing at 3 Squadron AFC’s ground at Villers-Bocage. An engine problem may have been the cause as Dibbs returned in the same machine (D6891) to Reclinghem the day after.

Did he make it to the meet?

Two other pilots from the squadron made forced landings, but it’s not clear whether these incidents occurred before or after the pilots attended the race meeting.

A large crowd watches the finish of a horse race at the 4th Australian Divisional Race meeting at Allonville. Image: AWM E02739

On 18 August, on a twilight patrol, Dibbs made another forced landing, at the aerodrome of 21 Squadron RAF, probably due to bad weather. He returned to Reclinghem the next morning.

Dibbs flew eight patrols at the end of August that harried German reconnaissance machines.

Wreckage of a German biplane brought down in the British lines, near Inchy, 13 September 1918. Photographer: John Warwick Brooke. Image: IWM Q 11915

On 27 August, Davies, leading a flight of five including Dibbs, crashed a Fokker east of Arras over Lécluse.

An Air Fight, France, 1917-18 : formation of six SE5 machines and six Albatros Scouts in combat. Harold Wyllie, 1920. Image: IWM ART 3199

The front north of Cambrai became the focus for operations in September 1918, with large formations sweeping German airspace beyond the front. Dibbs flew about 15 patrols this month.

Captain Roby Manuel’s report for 24 September is probably typical of Dibbs’ experience. On this occasion the British and Australian ‘circus’ comprised of 2 and 4 Squadrons AFC and 88 Squadron RAF.

We left the ground at 0900 and completed rendezvous over Merville with B.Fs [Bristol Fighters of 88 Sqn RAF] and Camels [of 4 Sqn AFC] at 0940 – height, Camels about 9,000 feet, SEs 11,000 to 14,000 feet and B.Fs 14,000 feet and over. We moved off towards La Bassee at a maximum distance of 1,000 yards behind Camels, and crossed lines at 0950 between La Bassee and Lens at slightly higher altitude, 12,000 ft. As we crossed lines I saw several EA in the distance but as we approached they disappeared in the clouds. We continued with the Camels following a course Annoeullin, one mile west of Seclin – Haubourdin – Perenchies, round North of Armentieres. The Bristol Fighters, who were following at a great distance, left us between Seclin and Haubourdin, flying in a southerly direction. This was the last we saw of them. Slightly east of Armentieres I sighted a Camel strafing a balloon; taking it to be one of No. 4 Squadron’s I sat around protecting it until machine crossed the lines. We then turned SE and crossed over Sainghin – by this time the Camels were on their way home. No other EA except those first mentioned were seen were seen except doubtful two seaters high up. On our way home we shot down a two seater out of control East of La Bassee.

In his combat report, Manuel gives more detail on the downing of the two-seater:

At 10.30 this machine was flying west of La Bassee at 10,000 feet. Capt Manuel followed underneath its tail about mid-way between La Bassee and Bethune and pulling down his Lewis Gun, fired a whole drum into EA from a range of 200 feet. The machine was turned over and went into a vertical nose dive. Capt Manuel half rolled and dived onto it again twice firing a burst from his Lewis Gun. Lieuts. Smith, Wellwood, Franks and Knight all dived on the EA which dived practically all the way down until it disappeared into the clouds. “D” A.A. Battery confirms this machine out of control.

S.E.5a pilot demonstrates firing the wing-mounted Lewis gun. Image: AWM H11941

The squadron book records another forced landing for Dibbs on 30 September at Saint-Floris. It may have been this incident.

One fine morning we took off in formation toward the line and while we were still lower than 1,000 feet my engine suddenly quit. I had to spiral down and land in the general direction of the wind, in a shell-holed field, which was also very fortunately soft and muddy. I very gently set the S.E.5 down, keeping the nose up for as long as possible and pancaked among the shell holes. To my intense surprise, and I might add relief, the machine sat herself down very nicely, and then tipped gently forward onto her nose, without even breaking the propeller.

I was near a detachment of the King Edward’s Horse, a famous cavalry regiment, and an Empire Unit. A number of the cavalrymen came to my aid, and an officer placed a guard over the machine, then took me along to their mess. They furnished me with a very nice dinner, and I spent the night with this detachment, while they very kindly sent a messenger over to the squadron to let them know what had happened.

The following morning a Crossley Tender arrived from the squadron with about 4 or 5 members of the ground staff. They had a good look at the S.E., and decided in the end that there was nothing seriously the matter with it. So about 30 members of the cavalry unit assisted us once again and bodily lifted the machine out of the field in which I had set down, and carried it over into the next field, which was not so badly shell-pitted. I was able to see a fairly straight and level run between the holes, and so while the mechanics started the engine, I arranged with as many as I could to hold the machine down for take off. There were 20 or more hanging on to the wing tips and some on to the tail.

I revved up the engine as much as I dared, dropped my upraised hand as a start signal, and they all just let go. The S.E. staggered down the short runway between the shell holes, and lurched into the air. I gained a little flying speed and was on my way back to Rechlinghem to report to the Squadron Commander.

16 August 1918. Bombing raid on Haubourdin aerodrome by 2 and 4 Sqn AFC with 88 Sqn RFC. Dibbs did not take part in this raid. Image: AWM P02163.003. (AWM caption dating this photograph to 17 October is incorrect. See Cutlack, p. 324.)

In October, Allied airfields moved east as the airmen followed the German armies in retreat. Dibbs’ squadron moved first to Serny (1 October) then to Auchel (21 October) and finally Pont-a-Marcq (26 October), a captured German aerodrome south of Lille.

The squadron harassed the enemy’s withdrawal with low altitude strafing and bombing, attacking its roads, railways and aerodromes. Large numbers of German aircraft took to the air in a desperate rearguard action. 13 enemy aircraft were destroyed and 19 sent out of control for a total of 32 aerial victories in the month, a record for the squadron. Two Australian pilots were killed in action.

A computer render of S.E.5a (D6995) flown by Lieutenant Frank Alberry of 2 Squadron AFC. He claimed all 7 of his victories in this aircraft between 16 September and 4 November 1918. The aircraft displays the squadron marking of a white vertical bar below the cockpit. The vertical bar replaced the earlier boomerang symbol. The “Y” on the fuselage is the fighter’s individual letter. The roundels have unusual proportions. Image: Panthercules, Rise of Flight forum

Dibbs flew 13 combat patrols in October 1918.

At dawn on 7 October, 18 machines of 2 Squadron AFC, each carrying four 25 pound Cooper bombs, rendezvoused with 10 Bristol Fighters of 88 Squadron RAF at 2,000 feet just east of their aerodrome at Serny. In squadron formation, they crossed the frontline near Wavrin at 6,500 feet, then dived, passing under a formation of 5 Fokkers that were later engaged by the Bristol Fighters, to a point two miles east of Fives station.

We crossed the line at about 5,000 feet, which was exceptionally low for any machine, and from there put the nose slightly down and go hell-for-leather for ground level 6 or 7 miles over. This gave us quite a good turn of speed. At point of attack, we would pair off, and operating in pairs, pick out our own targets.

The six machines of Dibbs’ “A” Flight, led by Eric Cummings, attacked the railway yards at Annappes –

– flying along the station at roof level, one after the other. As we passed by we could hear the rattle of M.G. fire, but we were down only about 30 feet from the ground and were pretty hard to hit. There were very few casualties in that sort of job. We would leave the fire of one gun behind and immediately pick up the fire of another, and so on the whole length of the platform. We dropped our four 25-lb bombs on the trains, or the station itself, or any other military objective we could see. Edgar Davies knocked over a building, which he said looked like a signals box, and claimed this in his combat report.

Dibbs dropped his four bombs from 50 feet and strafed trains and troops at the siding from 200 feet. Buildings and transport were also hit in an intense 20 minutes.

Result of an RAF bombing raid on the station at Ghislenghien, Belgium. Image: John Arthur ‘Jack’ Wilson / Jonathan Vernon

Meeting up with the larger formation over Lille, the squadron flew back to the line at 1,000 feet, shooting up with remaining ammunition a balloon that was on the ground, anti-aircraft defences and machine gun posts.

Coming back was something too. As low as we were, we would drop down even lower, and “hedge-hop” all the way back to our own lines. It was terribly exhilarating, over 6 or 7 miles of Hunland, till we reached home. Skimming over the fields, over a row of trees or a house and down again, we were too low for the anti-aircraft gunners to bear their sights onto us. They really had no hope of hitting us at that height. Sometimes a field battery would open up, but their luck was no better. If you saw a line of flashes, say on a hedge line, you simply flew into it and put a burst of fire down, and they would shut up.

A low-flying enemy aircraft, startled perhaps by the formation approaching it, dived nose-first into the ground without a round being fired at it.

Dibbs and his fellow pilots were back for breakfast at 7am.

Edgar Davies got a pat on the back for his destruction of that Signals Box. Later, after the Armistice, Edgar and I went up to Fives to have a look at the damage. Sure enough, he had knocked over a station building, but instead of being a signals shack, it turned out to be a men’s lavatory. In any case it must have caused a lot of discomfort to members of the German Army, even if it contributed little to their disorganisation.

Fokker D.VII F 4429/18 (0443-037). The Fokker D.VII entered service in May 1918. Its boxy, ungainly appearance is at odds with its maneuverability and performance which was deadly. Image: Wingnut Wings

A week later, 14 October, on a morning that drew fine and clear, Cummings and Captain F R Smith led two flights of S.E.5s across the lines, Smith’s patrol to bomb Fretin railway station, and Cummings’s “A” Flight to escort Smith.

Eric Cummings was leading, and spotted an enemy formation below. When he fired the red Verey light signal, I dived down from the upper level with him and we engaged with a formation of 16 Fokker D.VII’s.

Cummings fired a short burst of about 20 rounds from 100 yards into one Fokker, which dived steeply away, but in his descent the German must have seen the machines of Smith’s bombing formation approaching, and zoomed up again eastward. Cummings was waiting for this and dived on the Fokker again. When he put in a second short burst from 50 yards, the enemy aircraft turned on its side and fell to a crash near Cysoing.

The Australians pursued the enemy in a running fight eastward.

I picked on the straggler tagging along on the end of the line, on the assumption that he was one of the less experienced members to be occupying such a spot. I dived into him with both guns blazing. Somehow, during the course of the fight, we found ourselves flying headlong at one another. We had been told during training that in the event of such an occurrence, we had to keep going – which is playing “chicken” with a vengeance. However, we were approaching each other at quite considerable speed, and the German machine disappeared under my wing. I do not really know whether I shot him down or otherwise, but we certainly exchanged a considerable quantity of ammunition.

I looked around, but could only see one other S.E.5 – there were Fokkers everywhere. So I flew over towards it and recognised Geoffrey Blaxland’s aircraft. He zoomed up suddenly, and I followed him up, but meantime the Huns had apparently had enough, and were breaking off to go home. They dived off in an easterly direction, and so we proceeded on our way back to our own lines. Then suddenly, a formation of about 6 or 7 Fokkers dived past us flying from the south, apparently without having seen us. And although one of my guns was jammed, I could not resist the temptation of pulling up the nose and firing a long burst at one of the rear machines of the group. I did not know it at the time, but BOTH of Blaxland’s guns had jammed. The Fokkers half-rolled and came down on us like a ton of bricks. We immediately put our noses down and dived vertically away, being in no position to argue the point with them. We must have reached 300 mph and that was the end of the scrap.

We did not see the remaining members of our own formation from whom we had been separated in the fight, until we landed at the aerodrome.

In the fight against the Fokker D.VIIs, Cummings crashed one and sent two out of control. Blaxland destroyed one in flames and sent another out of control. Smith’s patrol, encountering another formation of D.VIIs, was also successful, claiming one in flames and two crashed.

Business end of a Fokker D.VIII. Replica aircraft built by The Vintage Aviator Ltd. Image: The Vintage Aviator

On 18 October, the day on which Lille was retaken, 2 Squadron raided Froyenne aerodrome and railway stations on the outskirts of Tournai. Cutlack writes:

Cummings, leading the squadron formation, descended over Hertain on a train mounting an anti-aircraft battery and on much transport collected alongside it. One of his bombs fell directly upon one gun of this battery and another exploded a dump near by. Simonson, Roberts, and Dibbs hit the train which Cummings had attacked, or the transport alongside it. Some of the escorting Bristol Fighters did the same. Transport was overturned, many horses fell, the locomotive was hit twice by bombs, trucks and carriages began to burn, and men scattered and dropped in all directions.

Dibbs reported 4 hits on the train at Hertain from 50 feet — two on the engine, one on the truck.

On 24 October 1918, Dibbs went on leave to the UK, returning to France for the last big raid flown by the Australians in the First World War.

Damage caused by British air raid on Thourout railway station. Image: IWM Q 42241

In the early afternoon of 9 November, 15 machines from 2 Squadron AFC joined a five squadron formation of bombers and scouts that attacked roads and railways choked with troops and transport between Ath and Enghien, south-west of Brussels. With no air cover needed, even the escorting patrols flew low to join in the destruction. The German retreat was now a rout.

The formation leader, Major R S Maxwell, 54 Squadron RAF, reported:

The ground targets were so obvious and numerous that every pilot and observer kept firing until stoppages or lack of ammunition compelled him to cease. The damage done and confusion caused was almost indescribable and impossible to give in detail.

Armistice

Hostilities ceased at 11am on 11 November 1918 with the signing of the Armistice.

S.E.5a of 2 Squadron AFC landing near Lille, 16 November 1918. Image: AWM E03727

Dibbs was sick for two days in November but there is no indication as to symptoms or cause in the squadron record book. He looks to have escaped the flu pandemic. In the last week of October there had been 87 cases of influenza in the squadron, 14 being evacuated to hospital. Between December and February 1919, three members of the squadron succumbed to the illness.

Flying also retained its attendant risk. Practice in aerial fighting, gunnery and formation flying continued at the squadron. Within three days of reporting back from sick leave came the inevitable forced landing, on 1 December, followed by a more spectacular flip two months later, on 10 February 1919.

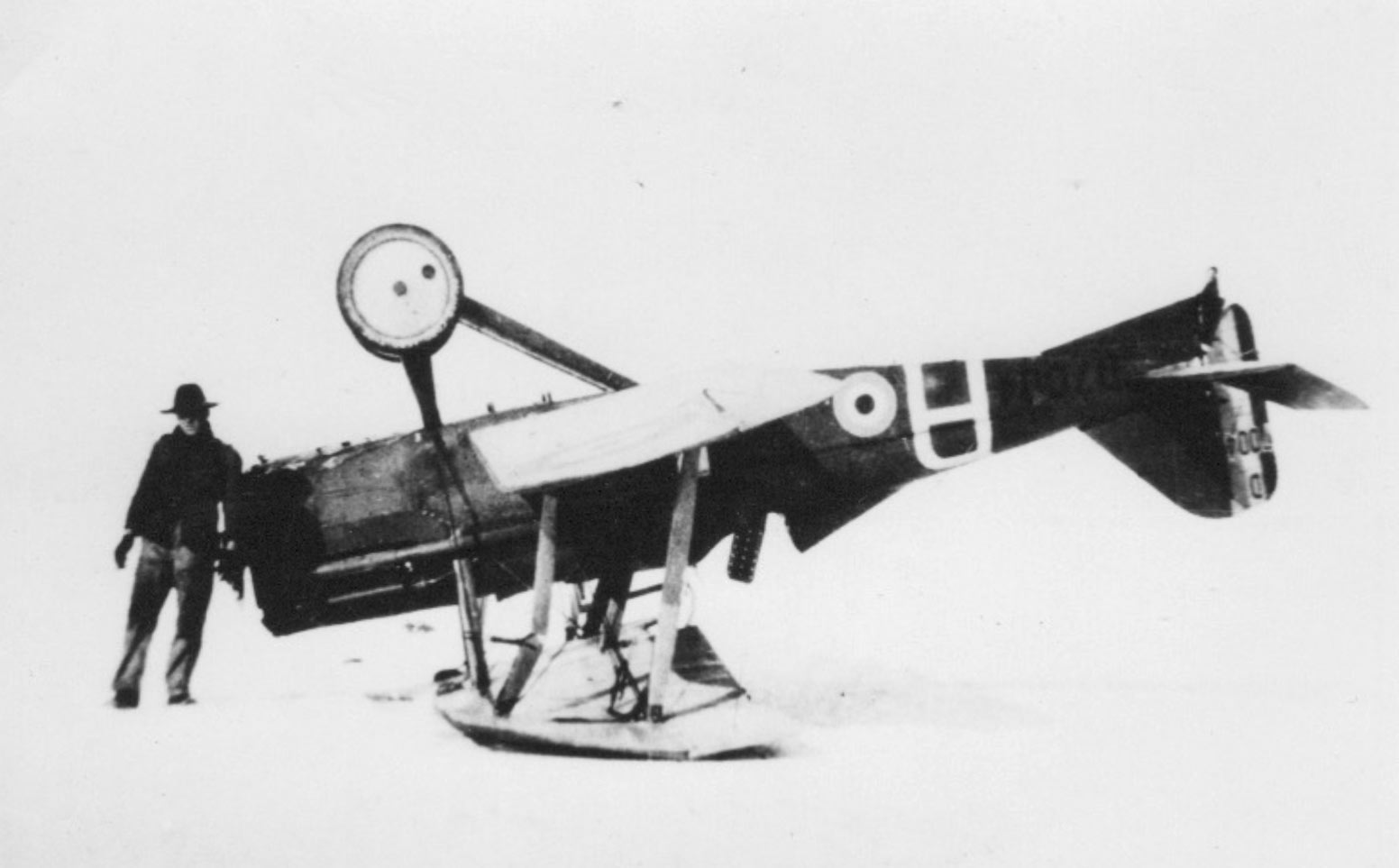

Delivering mail by air, Dibbs made a good landing in S.E. D7004 on a snow-covered aerodrome at Ruisseauville near Fruges. As he taxied across the field, he didn’t see a sunken road at the end of the ‘drome until he fell into it, the aeroplane turning a complete somersault28.

Dibb’s S.E.5a (D7004) at Ruisseauville, 10 February 1919, after running into a snow-filled road while taxiing across the aerodrome. Image: Joanne Howard née Dibbs

Dibbs also had the opportunity to fly some German aeroplanes that had been impounded.

[S]ome of us went to Nivelles near Brussels, and took over a number of German aircraft of many types. It was my privilege to fly a Fokker D.VII back to Serny in France, and a little later to fly an L.V.G. 2-seater back to England.

This machine I left at Lympne, and took a large Armstrong Whitworth the next morning to the National Aircraft Factory at Croydon. On account of the terribly foggy conditions, I could not locate the aerodrome, and came down in the exceedingly restricted space of the factory yard. It caused a great stir, and the employees poured out of the factory to see the strange sight.

I was duly informed that the usual practice was to land across the road on the runway, where the machine would be dismantled prior, you understand, to delivery to the factory.

With lots of time on their hands, sport was a popular form of recreation for the airmen. Friendly but competitive matches were played against units around Lille. The squadron took on a British artillery battery that boasted a rugby league international who had toured Australia with the English team in 1913-14.

The squadron war diary also records a weekly hunt with ‘any stray dogs found in or about the billets.’

With our “Beagles” the Squadron was able to claim many victories, and on one occasion were credited with the only hare for the day.

Whether Dibbs took part in these entertainments is not known, but he did take to the stage.

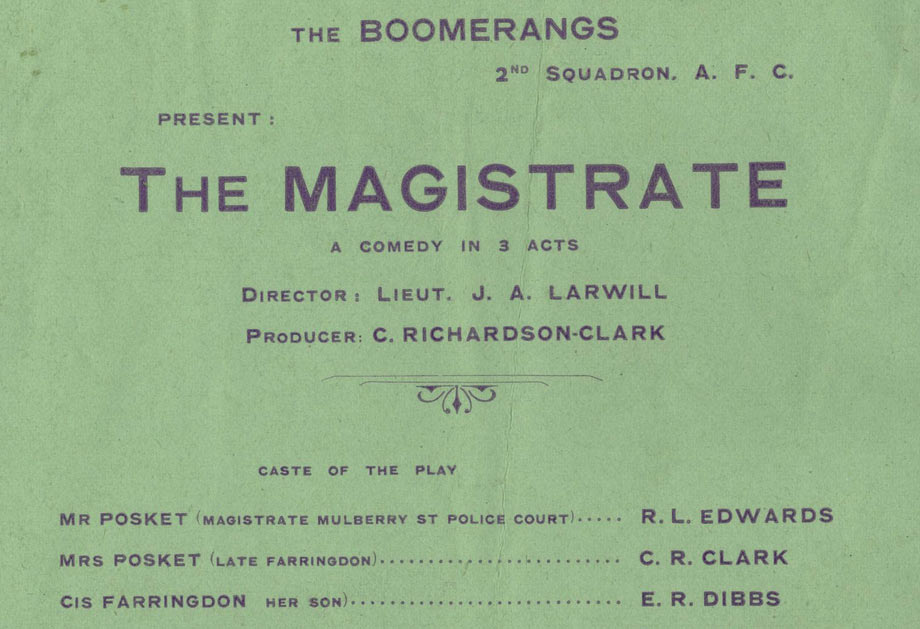

The Boomerangs, program for a performance of the play ‘The Magistrate’ given aboard HMAT (SS) Kaiser-i-Hind. View: cover, inside pages. Image: AWM PUBS002/001/001/002/014

In January 1919, the squadron concert party The Boomerangs debuted The Magistrate, a comedy in 3 acts, to a crowded house. Dibbs played Cis Farringdon. The show, says the recording officer, played to large and appreciative audiences at other units, and the program for a performance on the ship home is in the Australian War Memorial collection.

For Dibbs there was time for one more ‘crash.’

On the way home in May 1919, he injured an ankle climbing up the side of the troop ship Kaisar-I-Hind after a swimming race in the Suez Canal.

Australian Flying Corps. The finals of the 50 yard swimming race at Port Said, Egypt, 16-18 May 1919. As viewed from the Kaiser-I-Hind. Image: Australian Army Flying Museum

After a brief spell in a military hospital in Australia, he rejoined the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney.

After the war

Dibbs, living at 78 Rangers Road, Cremorne, married Meredith Glover, a trained nurse, at St Phillips church in The Rocks on 13 April 1921. They set up home in Bertha Road, Cremorne, then at “Farita” Wunda Road, Mosman.

In 1923 they moved to Wagga Wagga where the first of their five children was born. Alan Grahame (‘Peter’) Dibbs followed in his dad’s footsteps, flying Mosquitos in WWII. Alan’s siblings were Warren Eric James, Meredith Wendy, John Wardrop and Helen Jocelyn Dibbs.

Eric Dibbs retired from a life-long career with the bank in 1957 as manager of the Double Bay branch. He had remained active in the RSL and reserve forces for many years.

The end was in the 20th Light Horse in Victoria at the time of Munich. I was properly dressed wearing emu plumes, spurs, and pilot’s wings. General Squires passed the rather dry remark, “Dibbs, you appear to have tried all the forms of transport.”

Eric died in 1977. His wife Meredith passed away in 1985 at the nursing home “Villiers” in Mosman.

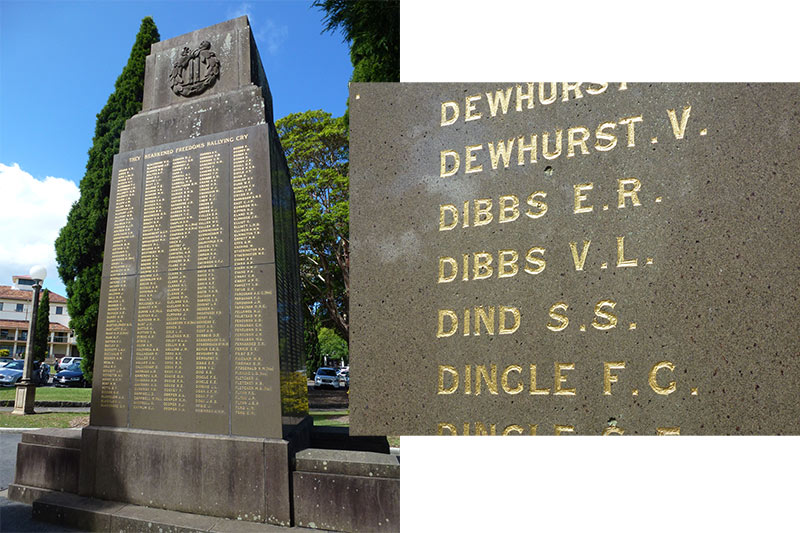

Mosman War Memorial

If you look at the south face of the Mosman War Memorial, you will find the name DIBBS E. R. inscribed.

Our man is also listed on the WWI honour roll of the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney. The elegant building that once housed the bank on George Street opposite Martin Place is now a Burberry store. The memorial to officers of the bank who served in the Great War can still be seen – appropriately for a natty dresser like Dibbs – in the menswear section.

Sources

Eric Dibbs’ narrative

- ‘Interview with Captain Eric Rupert Dibbs / Formerly of the A.F.C.’, 14-18 Journal, Australian Society of World War I Aero Historians, 1967, pp.86-101

- Dibbs, Eric R & Morton, Fred. (Interviewer) 1976, Eric Dibbs interviewed by Fred Morton in the Australian aviators in World War I oral history project

- Gwynn, Joanne 2013, The Dibbs family : from Scotland to Australia 1766-2013, Joanne Gwynn, nee Dibbs, [New South Wales?]

- Dibbs family 1828-1962, Papers

Military records

National Archives of Australia

Australian War Memorial

- AWM4 Subclass 1/46 – General Staff, Headquarters 3rd Australian Division

- AWM4 Subclass 8/5 – No 2 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps

- AWM4 Subclass 8/6 – No 3 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps

- AWM4 Subclass 8/9 – 6th Training Squadron, Australian Flying Corps

- AWM4 Subclass 23/53 – 36th Infantry Battalion

National Archives, UK

- AIR 76/133/21 Dibbs, Eric Rupert / Officers’ Service Records (PDF download)

- AIR 27/161 Appendices, 11 Squadron History 1914-1919 / Air Ministry and successors: Operations Record Books, Squadrons

Published histories

- Cutlack, F. M. 1941, The Australian Flying Corps : in the western and eastern theatres of war, 1914-1918, 11th ed, Angus & Robertson, Sydney

- Henshaw, Trevor 2014, The sky their battlefield II : air fighting and air casualties of the great war : British, Commonwealth and United States air services 1912 to 1919, Revised and expanded second edition, London Fetubi Books

- Molkentin, Michael 2010, Fire in the sky : the Australian Flying Corps in the First World War, Allen & Unwin, Crows Nest, N.S.W.

- Molkentin, Michael. 2014, Australia and the war in the air, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, Victoria

- Raleigh, Walter Alexander Sir & Jones, H. A. (Henry Albert), 1893-1945, (author.) & Great Britain. Committee of Imperial Defence. Historical Section 1922, The war in the air : being the story of the part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force, Oxford Clarendon Press

- Smith, Neil 1989, ‘Flying with 3 Squadron, AFC’, 14-18 Journal, Australian Society of World War I Aero Historians, pp.69-85

- Wrigley, H. N. (Henry Neilson) 1935, The battle below : being the history of No.3 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps, Errol G. Knox, Sydney

Websites and databases

- Items tagged “Eric Rupert Dibbs” in Trove

- Australian Society of WW1 Aero Historians: Australian Airmen of the Great War 1914-1918 database

- Neil Leybourne Smith’s History of 3 Squadron, AFC

- Commercial Banking Company of Sydney: people

Acknowledgements

Eric Dibbs’ granddaughter Joanne Gwynn shared some fantastic photos, and her recent book on the Dibbs family history was a great help. The Australian Society of WWI Aero Historians kindly permitted the interview with Dibbs printed in the Society journal in 1967 to be excerpted at length. Its president Gareth Morgan helped with questions of squadron routine and aviation history. Trevor Henshaw checked his records to help track down Dibbs’ crashes. Scott Wilson’s knowledge of the AIF was invaluable not only when interpreting Dibbs’ photos.

Footnotes

1 The government sold Graythwaite to Sydney Church of England Grammar School in 2009. The rehabilitation centre at Ryde was built with the proceeds of the sale. Still extant at Graythwaite is a small plaque for Thomas Dibbs on a door that leads off from the foyer (“T.A. Dibbs Ward 1915”) and a tablet in the Chapel dedicated to Owen Dibbs.

2 Another Mosman pilot – Garnet Malley – is credited in that preface.

3 Unless otherwise noted, quoted passages are from these sources.

4 Lieutenant Vernon Lyall Dibbs (25 June 1896 — 28 November 1969), 36th Battalion, AIF.

5 Michael Molkentin, Training for war: the Third Division AIF at Lark Hill, 1916, AWM MSS2081

6 Major John Henry Francis Pain, DSO, MC (1893-1941)

7 The other brothers were Alan Richard Baden, Ralph Oswald Cleveland, Cedric Ronald Houston and Hedley Claude Wilson Pain. Ralph Pain was killed in action at Fromelles.

8 Captain John Canning Lethbridge Barnett (27 May 1894 – 26 November 1923). His nickname refers to the brass attachment on the end of a string that was pulled through a rifle for cleaning. A piece of flannel was fed through the brass. It was a typical Australian nickname for a tall, fair-haired pom.

9 These were the first and second of Mauduit’s nine confirmed claims.

10 The citation for Raymond-Barker’s Military Cross does not quite tally with Dibbs’ account. It reads: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty when leading a fighting patrol. He attacked a large hostile formation, destroying two of them. He has also done excellent work in leading distant photographic reconnaissances, notably upon two occasions when his skilful leadership enabled photographs to be taken of all the required hostile area in spite of repeated attacks from enemy aircraft. He has helped to destroy seven hostile machines, and has at all times displayed conspicuous skill and gallantry.” The London Gazette (Supplement) no. 30287, p. 9581, 14 September 1917.

11 1930 ‘A DAY WITH THE FLYING CORPS.’, The Murrumbidgee Irrigator (Leeton, NSW : 1915 – 1954), 24 April, p. 3, viewed 15 January, 2016, http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article155900516

12 Trevor Henshaw’s work shows 14 dead, 8 wounded and 6 POW for 11 Sqn RFC between 11 June and 17 September 1917, but the squadron history (AIR/27/161) notes 4 of the wounded subsequently died of their wounds. The author admits to only a quick tally of these two sources.

13 An 11 Squadron observer was killed in action on 16 September. This was 3AM U Cox. Dibbs was posted to 3 Sqn AFC on 17 September where he is recorded as taking a test flight on 18 September. Lt G E Miall-Smith MC and 2/Lt C C Dennis were killed in action over Le Catelet on 25 September. A letter from George Miall-Smith to his parents, found in Tommy’s War: The Western Front in Soldiers’ Words and Photographs by Richard van Emden, delivers a very fine description of an 11 Squadron patrol.

14 Of the seven officers in the AIF who trained as observers and served with British units, Cutlack’s history records that “Lieutenants K. W. Holmes and C. R. Edson lost their lives. Lieutenant A. G. Bill was seriously wounded, and his pilot killed, in an action from which the Australian observer, with great difficulty, landed the machine. On recovery from his wounds Bill was transferred to kite-balloons. […] Lieutenants Dibbs, V. P. Barbat and S. J. Moir were ordered to leave their British squadrons and join No. 3 Squadron at Savy, which they did. The seventh man, Lieutenant B. J. Blackett, remained with the R.F.C. on intelligence work.”

15 Lieutenant Sydney James Moir (b. 1892), dental student of Canley Vale, NSW.

16 Lieutenant Vincent Pierce Barbat (b. 1892), draughtsman/engineer of Ipswich, Queensland

17 Lieutenant Alan Hamilton McLean Paterson (b. 1984), mechanic of Armadale, Victoria.

18 Captain Reginald George David Francis, DFC, pharmaceutical chemist of of Geelong, Victoria. Embarked 17 January 1917. Awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for conspicuous bravery and marked ability. Returned to Australia 4 June 1919.

19 Captain Ernest James Jones, MC, DFC, of Victoria. Awarded the Military Cross and Distinguished Flying Cross. Prominent in civil and commercial aviation in Australia after WWI. Died 6 October 1943.

20 Air Vice-Marshal William Hopton Anderson OBE CBE. Born 30 December 1891 at Kew, Melbourne. Awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Belgian Croix de Guerre. Held senior appointments in RAAF. Died 30 December 1975. His observer on this patrol was Lieutenant K C Hodgson.

21 Camblain-l’Abbé, aerodrome of 16 Squadron RFC.

22 Major Allan Murray Jones MC, DFC. Born 25 February 1895. Pharmacist of Caulfield, East Victoria. Had a distinguished career in military and civil aviation. Died 8 December 1963. Dibbs: “Our paths crossed quite a lot, in training and in No. 2 Squadron. Later I saw a good deal of him in civil life when I was bank manager at Double Bay.”

23 Lieutenant Eric Duncan Grant (b. 1898), student of Melbourne. Killed in a flying accident, 4 April 1918.

24 Lieutenant James Stuart Leslie Ross (b. 1895), telegraphist and cable officer of Moruya, NSW. Died 13 November 1919 in a flying accident.

25 Lieutenant George Ernest Holroyde (b. 1984 in Brisbane, Queensland), station hand.