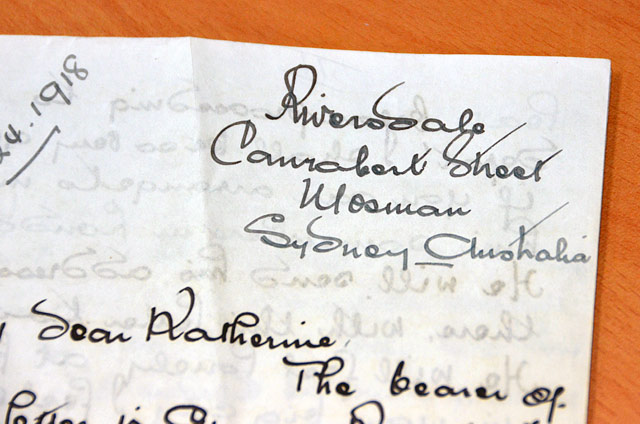

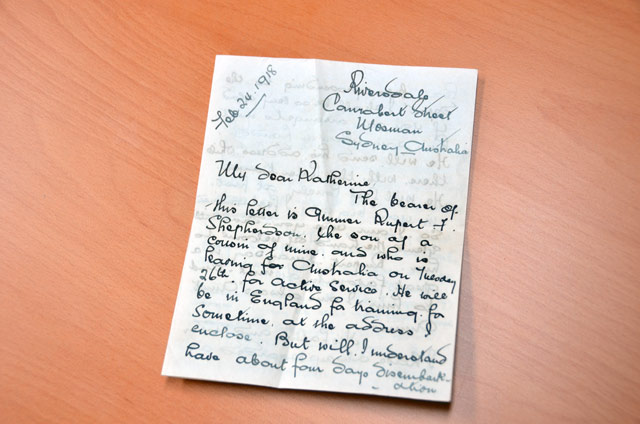

Last November I wrote a story for this blog about the life of Mosman soldier Sergeant Selwyn Robin. I had stumbled across Selwyn Robin whilst researching a short letter I obtained that was written from Mosman in February 1918. The letter was written by Selwyn’s mother, Mrs Annie Renfrey Robin, from her home at the time, Riversdale in Canrobert Street, Mosman.

The letter served as an introduction for Gunner Rupert Farquhar Shepherdson to Mary Katherine Whiting who was living in London. Rupert was the son of one of Annie Robin’s cousins and Katherine Whiting had recently married Annie’s eldest son Herman, a serving A.I.F soldier, whilst he was recovering from illness in England.

A transcript of the letter follows –

Riversdale

Canrobert Street

Mosman, Sydney, AustraliaMy Dear Katherine,

The bearer of this letter is Gunner Rupert F Shepherdson, the son of a cousin of mine, and who is leaving from Australia on Tuesday 26th for active service. He will be in England for training for sometime, at the address I enclose. But will I understand have about four days disembarkation leave before proceeding to the Depot. I shall be so very glad if you can arrange to meet him somewhere in London.

He will send his address, while there, with this letter to you. He will feel lonely at first, in your big city. I feel convinced. So I am sure you, dear, will lend the hand of welcome to him. Rupert I may say is a great favourite of mine, and to him, I am always “Aunt Annie”.

His father and mother I have always regarded as brother and sister. Since my own dear boys went out, at the call of duty, they have done everything they could to make me feel less lonely, and I would like to know that my new daughter would act in the same way to their son. It would be such a comfort to them.

Rupert is a very nice boy – a young medical student and not yet twenty years of age.

I suppose our Dear Herman is at the front again (?). What a pity he was not given home duty as his eyesight is not good.

I shall write fully to you by the next outgoing mail.

With much love to you both,

Yours affectionately,

Annie R Robin.

The details of letters and postcards from the First World War like this provide us with insights on a personal level of how life was lived at the time and how the war affected those caught up in its momentous and turbulent events. Although only a short letter I thought it may be of some interest to the Mosman 1914-1918 project to elaborate on the writer and those mentioned within it.

The writer – Mrs. Annie Renfrey Robin

Born around 1862, Annie Renfrey Robin had married Edward Herman Robin at the age of 26 years in October 1888. The couple were both from pioneering Adelaide families but appear to have been based in Sydney for most of their lives. The marriage had produced four children, three sons (Herman, Selwyn and Rollo) and a daughter (Beryl) and at the time of writing the letter all three sons were serving the Empire amongst the ranks of the A.I.F.

So although Mrs. Annie Robin was to write “Since my own dear boys went out, at the call of duty, they have done everything they could to make me feel less lonely”, I feel sure that she was missing their presence and no doubt had fears for their wellbeing. The marriage of her eldest son to a woman in England was likely to have been unexpected.

The letter is written in a positive tone and no doubt she was looking forward to meeting her new daughter in law in the future. So although she was powerless to events unfolding in Europe, it was well within her power and a sensible thing to do to write a letter of introduction for her cousin’s son, soon to enter the war.

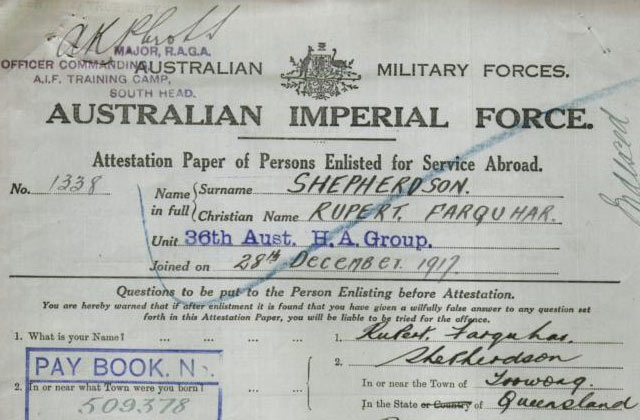

The letter carrier – Rupert Shepherdson

National Archives of Australia: B2455, SHEPHERDSON RUPERT FARQUHAR

The letter was carried by 1338 Gunner Rupert Farquhar Shepherdson, shortly to arrive in England. Rupert from Lindfield in Sydney’s north was a nineteen year old student studying medicine at Sydney University when he enlisted in the artillery on the 28th December 1917. He was amongst Reinforcement 17 of the 36th Heavy Artillery Group, which consisted entirely of men who had previous militia service with the Australian Garrison Artillery (AGA).

The Heavy Artillery Group was a unique arm of the First A.I.F, operating the largest artillery pieces in the A.I.F arsenal, such as the ground platform mounted 9.2 inch BL (breech loading) howitzer and the smaller carriage mounted 8 inch howitzer. The Heavy Artillery Group differed from other units of the A.I.F in being employed directly anywhere along the Western Front, under the command of any of the allied forces.

Rupert left Sydney on the 26th February 1918 as mentioned in the letter, sailing on to Melbourne where the rest of the reinforcement was gathered. The HMAT Nestor then embarked for England on the 28th February 1918. The ship arrived in Liverpool on the 20th April 1918 and immediately the reinforcement was marched in to the Heavy Artillery Training Depot at Bull Point Barracks, Devonport, near Portsmouth on the south west coast.

We can determine from Rupert’s service record and the Heavy Artillery Training Battalion’s war diary that he would remain in England until the 11th October 1918. This was the date that he departed for France, marching in to the Australian General Base Depot the following day.

Rupert was taken on strength by the 54th Heavy Artillery Battery on the 28th October 1918, where he remained until he was returned to England for early repatriation on the 19th March 1919. The 54th Heavy Artillery Battery was equipped with the 8-inch howitzer and Rupert spent fifteen days in action with them prior to the signing of the armistice on the 11th November 1918.

Herman Robin & Katherine Whiting

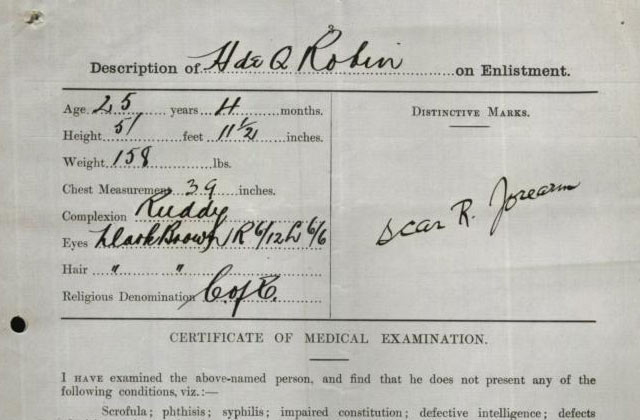

National Archives of Australia: B2455, ROBIN HERMAN DE QUETTEVILLE

With a clearer understanding of the letter writer and carrier, it is now worth looking at the lives of Katherine Whiting, the receiver of the letter and her new husband, Private Herman De Quetteville Robin. Mrs Annie Robin asks in the letter if Herman was at the front again. Herman was still in England at the time of writing, but the war was extracting a horrid toll upon his wellbeing, the enormity of which his mother seemed unaware of.

Herman enlists and serves at Gallipoli

Herman’s service records tell that he had been working as a bank clerk when he originally enlisted in Boulder, Western Australia, amongst the 6th Reinforcements of the 11th Battalion A.I.F on the 19th March 1915. He entered training at Blackboy Hill Camp in early May 1915 before being ‘discharged to allow of joining with brother in New South Wales’. By the 24th May 1915 he was back in Sydney and attested at Liverpool along with his younger brother Selwyn amongst the 7th Reinforcements of the 13th Battalion.

The 13th Battalion was formed in September 1914 at Rosehill Race-course as the New South Wales contribution to the 4th Brigade. The 4th Brigade was then commanded by Colonel John Monash. The 13th Battalion were sent to Melbourne in late November 1914, joining the Brigade’s other battalions and embarking for Egypt on the 23rd December 1914.

The 13th Battalion trained hard in Egypt prior to the landings at Gallipoli. They were amongst the A.I.F battalions that landed at Gallipoli on the first day and would remain there apart from a months rest on the Island of Mudros in late September and October 1915. Herman and brother Selwyn did not leave Australia for Egypt until the 20th August 1915 aboard the HMAT Shropshire.

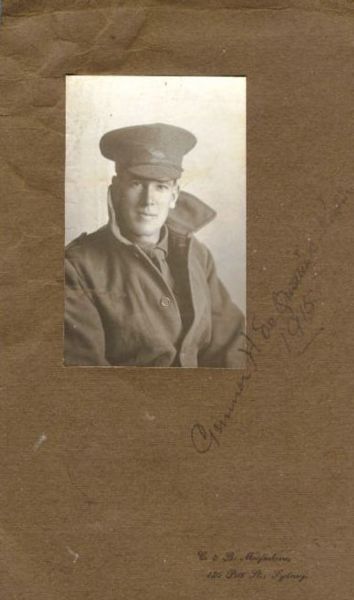

A photograph of Herman exists within the Mapping our Anzacs section of the National Archives, taken in Sydney just prior to his departure for Egypt.

Gunner Herman Robin prior to embarkation. Source: Mapping our Anzacs

The brothers, as I wrote in my previous story, were separated whilst in Egypt and Herman did not join the 13th Battalion until 23rd October 1915 on the Island of Mudros. The 7th and 8th Reinforcements arrived on that day and the Battalion History tells that a moonlight concert was held that night. The battalion would remain at Mudros for a further week before returning to Gallipoli on 1st November 1915.

By the end of August 1915 the major battles had been fought at Gallipoli and the peninsula became a quieter battle zone. That is not to say that it was without action and as the 13th Battalion moved back into the line at Durrant’s Post on the 3rd November 1915 men were still falling to sniper’s fire, bombardment and illness. The most peculiar aspect of November being the dust storms early in the month, followed by the big storm and floods of 25th November and finally the arrival of snow at Gallipoli on the 29th November 1915.

It was fortunate that the Battalion had prepared winter quarters underground on the 24th November 1915 to provide some protection from the elements as their uniforms were not suitable for service in the fast approaching winter. Herman’s time on the peninsular amounted to nearly two months and like the campaign it was coming to a close. Lord Kitchener had recommended an evacuation from Gallipoli at the end of November 1915 and the 13th Battalion were amongst the last men to leave on the 20th December 1915.

Return to Egypt and the doubling of the A.I.F

During the evacuation of the 20th December 1915, Herman sprained his ankle which led to him being sent to No.3 Auxillary Hospital in Heliopolis on 24th December 1915 after arriving back in Alexandria. He was discharged from hospital on the 11th January 1916 and re-joined the 13th Battalion on the 4th February 1916 at Moascar Camp.

When the A.I.F returned to Egypt after Gallipoli it became apparent to Major General Godley, who was in charge at the time, that the number of reinforcements in training would be too great to be absorbed by the returning 1st and 2nd Divisions. He put forward a plan that was accepted, that a 4th and 5th Division be created by splitting the infantry battalions of the 1st and 2nd divisions and using them as the nucleus for the creation of the infantry battalions for the new Divisions. The 3rd Division was at the time being formed and trained in Australia.

The 13th Battalion formed the nucleus of the 45th Battalion providing 10 officers and 363 other ranks. ‘The Fighting Thirteenth’, the battalion’s unit history indicates that Herman was amongst a group of 53 men from the Battalion who were sent to the 4th Division Artillery. Gunner Herman Robin was taken on strength by the 10th Field Artillery Brigade at Tel El Kebir on the 16th March 1916.

Arrival on the Western Front – June 1916

Herman left Alexandria with the 38th Field Artillery Battery of the 10th Field Artillery Brigade on the 5th June 1916 disembarking at Marseilles on the 13th June 1916. He would initially spend six months on the Western Front where the Brigade saw action at Pozieres and Mouquet Farm in August and September 1916 and later at Flers in October 1916.

Action on the Western Front and hospitalisation in England – 1917

On the 12th January 1917 whilst Herman was on leave in London he reported sick and was admitted to the 2nd Auxiliary hospital at Southall. He remained there until discharged on the 8th February 1917. Herman left for France on the 19th February 1917 and re-joined the 38th Field Artillery Battery on the 23rd February 1917.

He would remain at the front until the 13th June 1917 when he was admitted to a casualty clearing station (C.C.S) suffering from boils and piles. He was hospitalised at Etaples before being moved back to England and admitted to the 1st General Hospital in Birmingham on the 19th June 1917. During the period from late February until mid-June 1917 the 4th Division artillery had seen some heavy action worthy of closer scrutiny.

May 1917. Three members of the Australian Field Artillery using an 18 pounder gun in action at Noreuil Valley, during the fight for Bullecourt. AWM E00600

During early May 1917 the 10th Field Artillery Brigade moved into positions around the village of Bullecourt. They were tasked with supporting the 1st Anzac Corps who were due to attack and take the village which formed part of the Hindenburg Line on the 3rd May. This would be the second attempt the allies would make to seize the village; the first attempt had failed during mid April.

The Field Artillery Brigade had spent the 2nd May registering enemy targets and when the battle commenced at 3.45 am on the morning of the 3rd May all of the batteries were engaged in shelling the enemy. It would not be one sided as the 10th Field Artillery Brigade War Diary recorded that the enemy had retaliated with heavy shelling and machine gun fire from ‘several strong points near Bullecourt’. The Australian and British infantry would successfully meet their objectives over the following days, however heavy counter battery fire would take its toll upon the artillerymen.

The War Diary entry for 6th May 1917 highlighted the cost the enemy had taken upon the Field Artillery Brigade –

During today enemy counter battery work was very successful. 110th Battery had two guns damaged by shell fire and ammunition. Casualties during the last few days 20 killed 50 wounded.

A further War Diary entry for 8th May 1917 explains why the enemy was able to extract such a heavy toll –

A map was taken from a German prisoner printed on May 1st showing in detail our battery positions and camp. This accounts for the accurate counter battery work that has taken place during our stay.

The Brigade stayed in the line until 14th May when they started for camp at Ballieul. It would be a short stay, the Brigade moving back into the line on the 21st May where they remained until 16th June 1917. Herman had been in the line when he was evacuated to the C.C.S on 13th June 1917 – this may have been of some significance as I shall refer to later.

May 1917. An 18 pounder gun of an Australian battery in its sandbagged gun pit at Noreuil Valley, during the fight for Bullecourt in May 1917. Note that the gun is in full recoil after firing. AWM E00602

Hospitalised once more and marriage to Katherine Whiting

After Herman’s arrival back in Birmingham on 19th June 1917 his life became a little more complicated. He was transferred to the 1st Auxillary Hospital at Harefield on 26th July where he remained until 30th August when he was marched in to the No.2 Command Depot at Weymouth. On the 12th October Herman was moved to No.4 Command Depot at Codford. (The purpose of Command Depots was to assist in rehabilitating wounded, injured or ill soldiers in preparation for return to the Western Front.)

Whilst at Weymouth, Herman would have been granted short periods of leave from the Depot. On the 15th September 1917 he was in London, West Ealing to be precise, where he married Mary Katherine Whiting. It is not known when or where he met Katherine, however it is believed within the family that they met whilst she was working as a voluntary nurse when Herman was hospitalised.

Katherine was from a good family; her father William Henry Whiting being a naval architect was heavily involved in the construction of ships with the Admiralty. The eldest son William Robert Whiting was also a naval architect, whilst another son, Maurice Henry Whiting was an officer serving in the Royal Army Medical Corps. Additionally Katherine had two sisters, Muriel and Madeline.

The family was known for its generosity, though it is easy to imagine that there may have been concerns over Katherine’s marriage to an Australian soldier.

On the 22nd November 1917 Herman was sent to the Overseas Training Brigade at Longbridge Deverill, Hurdcott. Early in the New Year on the 22nd February 1918 he was marched up the road to the Reserve Brigade Australian Artillery (R.B.A.A) at Heytesbury. Herman was being prepared for his return to France.

A brief return to the Western Front – 1918

Herman landed in France once more on the 2nd March 1918 and rejoined the 38th Battery on the 7th March 1918. It appears that he was attached to Headquarters, 38th Battery, on his return, not with the guns. Herman would not remain in France for long, as he had an unfortunate accident on the morning of 18th April 1918.

The accident was witnessed by Gunner Arthur Povey, who saw Herman

… washing outside the billet, suddenly I heard a noise of glass, and saw Gunner Robin white in the face lying across the hothouse with hands through the glass.

Herman had slipped and put his right arm through a pane of glass and had cut it deeply, two inches above the wrist. He was immediately cared for by the Field Ambulance and was later admitted to the 5th General Hospital at Rouen. By the 24th April he was back in England at the 1st Southern General Hospital at Birmingham.

A report on the accident was carried out to determine if it was a genuine accident or self inflicted wound. The Commanding Officer determined the fall to be an accident and Herman free of blame. Herman was discharged from hospital and sent to No.3 Command Depot at Hurdcott on 11th May 1918.

The effects of war

Herman was once more awaiting his return to the front, whilst his personal circumstances were changing very quickly around him. At this point in time not only was he away from his wife, away from Australia and his family but additionally Katherine was pregnant, expecting within months.

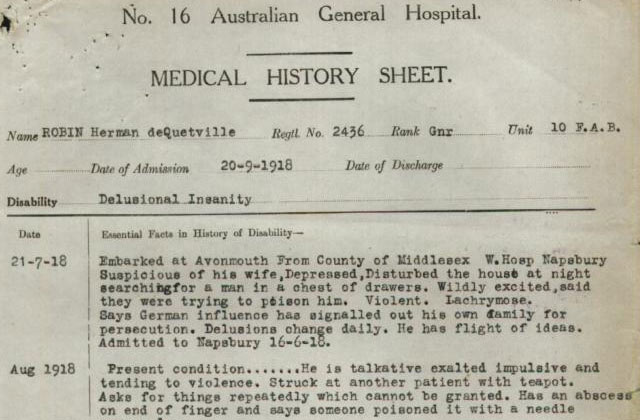

Herman was in a difficult situation and things just got worse. On the 14th June 1918 he was admitted to the 2nd Australian Auxiliary Hospital at Southall without a diagnosis being made. Two days later he was transferred to the County of Middlesex War Hospital at Napsbury, an establishment that prior to the war had served as an asylum.

A medical report was carried out by the medical staff in charge of Herman’s case on the 16th July 1918, which found that he was suffering delusional insanity, ‘constitutional’ but ‘aggravated by active service’ and recommended that he be discharged permanently unfit. Nearing one hundred years later it is difficult to comment upon the documents and develop an understanding of what was really afflicting Herman. Within the report there is a sentence reading that Herman went –

To France 1916. Rarely up with the guns. No history of wounds, gas or concussion.

I would disagree with the statement that Herman was rarely with the guns. Whilst it is true that he had been away from the front from June 1917 until his brief two weeks return in April 1918, this ignores his previous service. Herman had seen action at Gallipoli and during the first six months he spent in France from June 1916.

Whilst he had been hospital in England in early 1917 he was back in France for the 2nd Battle of Bullecourt as I mentioned previously in this story. The 10th Field Artillery Brigade suffered many casualties and it is difficult to understand how a gunner could not be ‘up with the guns’ and the counter battery fire they were susceptible to. There was nowhere to hide from artillery as many soldiers based behind the lines found out and I would suggest that Herman was suffering trauma from his experiences at the front.

National Archives of Australia: B2455, ROBIN HERMAN DE QUETTEVILLE

Herman’s behaviour was of serious concern, his medical history sheet recording that prior to hospitalisation he was

… suspicious of his wife, depressed, disturbed the house at night searching for a man in a chest of drawers … wildly excited … violent.

At one stage after being hospitalised he struck another patient with a teapot. On the 21st August 1918 he was sent home from England aboard the Transport S.S Boonah.

Return to Australia and the post-war years

Herman was sent home by himself leaving Katherine and a baby daughter Anne, born on the 18th June, to remain with the Whiting family. Times must have been difficult for all involved. When Herman arrived in Melbourne he would spend the first few months at No.16 Australian General Hospital at Mont Park.

Herman’s brother (Selwyn I assume) was contacted and before the end of the year he was allowed to return to Sydney under his brother’s supervision. Herman’s medical records end in April 1919 and what happened to him after this time becomes a little vague. It is believed that towards the end of 1919 he returned to England, no doubt to be with his wife and child.

Whether Herman recovered fully or otherwise is not known. When Herman passed away aged 46 years on the 21st March 1935 he was at Berrywood Hospital, an asylum in Northamptonshire. His obituary published in the Sydney Morning Herald by the family in Australia left no doubt as to what they believed to be the contributing cause – ‘result of war service’.

Katherine would live a long life, passing away in November 1989 at the age of 102 years. Their daughter Anne would also live a good life, qualifying as a schoolteacher and living until January 1999. Herman had been buried in the grounds of St. Lukes Parish Church at Duston; Katherine would later be laid to rest alongside him, as later would Anne’s ashes.

St. Luke’s Church, Duston, Northamptonshire. (Courtesy of Joe Fearon)

Postscript

As a postscript to this story, shortly after posting Selwyn Robin’s story on the Mosman 1914-1918 blog I received a message from Marian Sperberg McQueen, an American lady with an interest in Herman’s story. Marian had been researching her great uncle’s experiences during the war, largely through a collection of letters remaining that he had written.

Lieutenant Parr Hooper from Baltimore, Maryland was a twenty five year old pilot who was attached to No.32 Squadron R.A.F in 1918. Parr was raised and educated in Baltimore and had graduated as a Mechanical Engineer from Cornell University in 1913. He had been working in Philadelphia when America entered the war in early 1917 but left to enlist in the U.S army shortly afterwards.

Parr enlisted in the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and left for France in September 1917. Whilst training in England Parr would spend time during his leave with the Whitings, who were very hospitable towards him. He had been introduced to the family through his sister Mary, who had met Katherine’s oldest sister Muriel whilst travelling in Europe prior to the war.

In a letter Parr wrote from London to home on May 11, 1918, he made mention of meeting Rupert Shepherdson and Herman De Quetteville Robin at the Whitings –

There was to be a dance at the Inn that evening and I did not know whether to take it in or go out and say good bye to Whitings. I had purchased a pound of sugar, and a quarter lb. of butter on some ration tickets I had gotten for my ferrying job, and a box of chocolates which I wanted to take out to them. So after dinner I decided to go out. Mr. Whiting and Muriel were away, but I saw Mrs. Ralph, and the middle daughter, Katrini I believe, her husband an Australian soldier and his cousin (also an Australian soldier) were there. He is home to a recuperation camp, and his cousin is just on his way out. Katrini was looking fine and happy and they are to have a little child soon.

So we can safely assume that the letter did reach Katherine Whiting and that Rupert Shepherdson did spend time with the Whiting family and his cousin Herman De Quetteville Robin.

Unfortunately Lieutenant Parr Hooper was lost on the Western Front. Parr was killed in action during ground attack operations on 10th June 1918 whilst flying an S.E5 biplane with No.32 Squadron RAF. He was another casualty of that terrible war.

It is not known how Annie Robin coped with Herman’s return. He was being assisted by Selwyn, who it should be remembered had lost an eye at the Battle of Messines in June 1917. All three Robin boys returned home from the war, two of them in a vastly different condition than they had left our shores.

Annie Robin would live until 1929, passing away at Chatswood, aged 67 years. Rupert Shepherdson returned to Sydney University and continued with medicine, graduating in 1923. Rupert died in 1941.

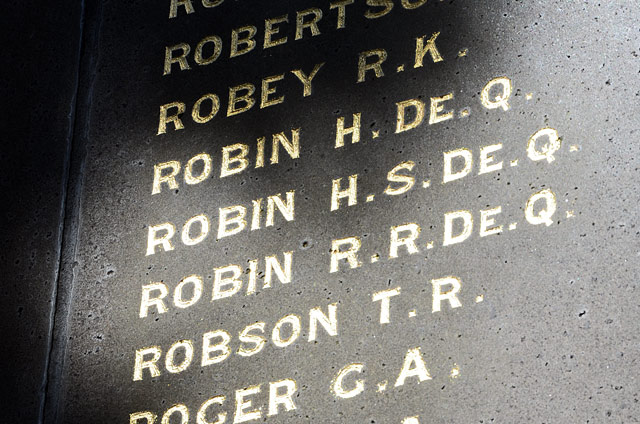

Mosman War Memorial

The Robin brothers are all named on the Mosman War Memorial. I hope this story is of value in understanding how the war affected the lives of a local family.

Sources

- Correspondence with Marian Sperberg-McQueen and Joe Fearon regarding the Hooper and Whiting families. Their help is appreciated.

- National Archives of Australia, B2455 Service records of Herman De Quetteville Robin and Rupert Farquhar Shepherdson.

- Various War Diaries of Headquarters 10th Australian Field Artillery Brigade and the Heavy Artillery Training Battalion.

- C.E.W Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18, Volume III The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1916 .Angus & Robertson.(12th Edition, 1941)

- T.A White, The fighting Thirteenth – The History of the Thirteenth Battalion A.I.F, Printed 1924 (Naval & Military Press Reprint 2009)

- Peter Burness, The Big Guns, Wartime Issue 26, 2004, Published by the Australian War Memorial

- Terry Crawford, Wiltshire in the Great War, Published by The Crowood Press 2012.

- Cornell Heroes – Members of the Class of Nineteen Hundred and Thirteen Who Lost Their Lives During the World War